Marasmus

| Marasmus | |

|---|---|

| |

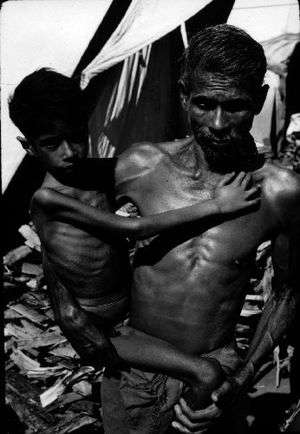

| Child with Marasmus in Nepal, 1972 | |

| Specialty | Critical care medicine |

Marasmus is a form of severe malnutrition characterized by energy deficiency. It can occur in anyone with severe malnutrition but usually occurs in children.[1] A child with marasmus looks emaciated. Body weight is reduced to less than 62% of the normal (expected) body weight for the age.[2] Marasmus occurrence increases prior to age 1, whereas kwashiorkor occurrence increases after 18 months. It can be distinguished from kwashiorkor in that kwashiorkor is protein deficiency with adequate energy intake whereas marasmus is inadequate energy intake in all forms, including protein. This clear-cut separation of marasmus and kwashiorkor is however not always clinically evident as kwashiorkor is often seen in a context of insufficient caloric intake, and mixed clinical pictures, called marasmic kwashiorkor, are possible. Protein wasting in kwashiorkor generally leads to edema and ascites, while muscular wasting and loss of subcutaneous fat are the main clinical signs of marasmus.

The prognosis is better than it is for kwashiorkor[3] but half of severely malnourished children die due to unavailability of adequate treatment.

The word “marasmus” comes from the Greek μαρασμός marasmos ("withering").

Signs and symptoms

Marasmus is commonly represented by a shrunken, wasted appearance, loss of muscle mass and subcutaneous fat mass.[4] Buttocks and upper limb muscle groups are usually more affected than others. Edema is not a sign of marasmus and is only present in kwashiorkor, and marasmic kwashiorkor. Other symptoms of marasmus include unusual body temperature (hypothermia, pyrexia), anemia, dehydration (as characterized with consistent thirst and shrunken eyes), hypovolemic shock (weak radial pulse, cold extremities, decreased consciousness), tachypnea (pneumonia, heart failure), abdominal manifestations (distension, decreased or metallic bowel sounds, large or small liver, blood or mucus in the stools), ocular manifestations (corneal lesions associated with vitamin A deficiency), dermal manifestations (evidence of infection, purpura, and ear, nose, and throat symptoms (otitis, rhinitis). Dry skin and brittle hair are also symptoms of marasmus. Marasmus can also make children short-tempered and irritable.[5]

Causes

Marasmus is caused by a severe deficiency of nearly all nutrients, especially protein, carbohydrates and lipids, usually due to poverty and scarcity of food.[6] Viral, bacterial and parasitic infections can cause children to absorb few nutrients, even when consumption is adequate.[7] Marasmus can develop in children who have weakening conditions such as chronic diarrhea.[8]

Treatment

Not only the causes, but also the complications of the disorder must be treated, including infections, dehydration, and circulation disorders, which are frequently lethal and lead to high mortality if ignored. Initially, the child is given dried skim milk powder mixed with boiled water which is then followed by mixing it with vegetable oils and finally sugar. Refeeding must be done slowly to avoid refeeding syndrome. Once children start to recover, they should have more balanced diets which meet their nutritional needs. Infections are also common in children with marasmus. So, they are also treated with antibiotics.[9] Ultimately, marasmus can progress to the point of no return when the body's ability for protein synthesis is lost. At this point, attempts to correct the disorder by giving food or protein are futile.

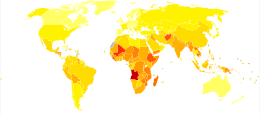

Epidemiology

Persons in prisons, concentration camps, and refugee camps are affected more often due to poor nutrition.

See also

References

- ↑ "What You Should Know About Marasmus". Healthline.

- ↑ Appleton & Vanbergen, Metabolism and Nutrition, Medicine Crash Course 4th ed. Moseby (London: 2013) p.130

- ↑ Badaloo AV, Forrester T, Reid M, Jahoor F (June 2006). "Lipid kinetic differences between children with kwashiorkor and those with marasmus". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 83 (6): 1283–8. PMID 16762938.

- ↑ Rabinowitz, Simon. "MD, PhD, FAAP". Emedicine Medscape. Medscape. p. 28. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- ↑ "What You Should Know About Marasmus". Healthline.

- ↑ "What You Should Know About Marasmus". Healthline.

- ↑ http://www.healthline.com/health/marasmus

- ↑ http://www.healthofchildren.com/P/Protein-Energy-Malnutrition.html

- ↑ "What You Should Know About Marasmus". Healthline.

- ↑ "Mortality and Burden of Disease Estimates for WHO Member States in 2002" (xls). World Health Organization. 2002.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |