Kingdom of Mapungubwe

| Kingdom of Mapungubwe Mapungubwe | |

|---|---|

| 1075–1220 | |

| Status | Kingdom |

| Government | Monarchy |

| History | |

• K2 and Schroda culture moves to Mapungubwe Hill | 1075 |

• Mapungubwe Hill abandoned and travels to different places | 1220 |

| UNESCO World Heritage site | |

|---|---|

| Location | Limpopo, South Africa |

| Criteria | Cultural: (ii), (iii), (iv), (v) |

| Reference | 1099bis |

| Inscription | 2003 (27th Session) |

| Extensions | 2014 |

| Area | 28,168.6602 ha (69,606.275 acres) |

| Buffer zone | 104,800 ha (259,000 acres) |

| Coordinates | 22°11′33″S 29°14′20″E / 22.19250°S 29.23889°ECoordinates: 22°11′33″S 29°14′20″E / 22.19250°S 29.23889°E |

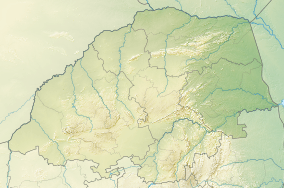

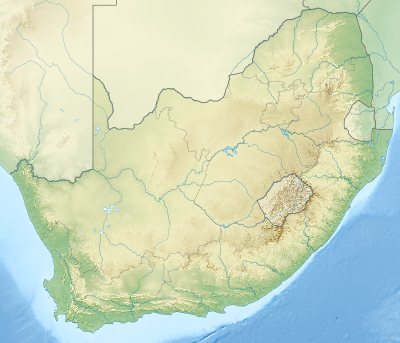

Location of Kingdom of Mapungubwe in Limpopo  Kingdom of Mapungubwe (South Africa) | |

| Historical states in present-day South Africa |

|---|

|

|

before 1600

|

|

1600–1700

|

|

1700–1800

|

|

1800–1850

|

|

1850–1875

|

|

1875–1900

|

|

1900–present

|

|

|

The Kingdom of Mapungubwe (1075–1220) was a pre-colonial state in Southern Africa located at the confluence of the Shashe and Limpopo rivers, south of Great Zimbabwe. The name is derived from either Venda or Shona. The name may mean "Hill of Jackals".[1] The kingdom was the first stage in a development that would culminate in the creation of the Kingdom of Zimbabwe in the 13th century, and with gold trading links to Rhapta and Kilwa Kisiwani on the African east coast. The Kingdom of Mapungubwe lasted about 80 years, and at its height its population was about 5000 people. The Mapungubwe Collection is a museum collection of artifacts found at the archaeological site and is housed in the Mapungubwe Museum in Pretoria.

This archaeological site can be attributed to the Bukalanga Kingdom, which comprises the Bakalanga people from northeast Botswana, the Karanga from Western Zimbabwe, the Vha Venda in the northeast of South Africa. They were the first Bantu to cross the Limpopo River to the south, and established their kingdom where the Shashe and Limpopo conjoined (Sha-limpo).

Origin

The largest settlement from what has been dubbed the Leopard's Kopje culture is known as K2 culture and was the immediate predecessor to the settlement of Mapungubwe.[2] The people from K2 culture, probably derived from the ancestral Khoi culture, were attracted to the Shashi-Limpopo area, likely because it provided mixed agricultural possibilities.[3] The area was also prime elephant country, providing access to valuable ivory. The control of the gold and ivory trade greatly increased the political power of the K2 culture.[4] By 1075, the population of K2 had outgrown the area and relocated to Mapungubwe Hill.[5]

Stone masonry

Spatial organisation in the kingdom of Mapungubwe involved the use of stone walls to demarcate important areas for the first time. There was a stone-walled residence likely occupied by the principal councillor.[6] Stone and wood were used together. There would have also been a wooden palisade surrounding Mapungubwe Hill. Most of the capital's population would have lived inside the western wall.[6]

Origins of the name

The capital of the kingdom was called Mapungubwe, which is where the kingdom gets its name.[5] The site of the city is now a World Heritage Site, South African National Heritage Site,[7] national park, and archaeological site. There is controversy regarding the origin and meaning of the name Mapungubwe. Conventional wisdom has it that Mapungubwe means "place of Jackals," or alternatively, "place where Jackals eat", thavha ya dzi phunguhwe, or, according to Fouché—one of the earliest excavators of Mapungubwe—"hill of the jackals" (Fouché, 1937 p. 1). It also means "place of wisdom" and "the place where the rock turns into liquid"—from various ethnicities in the region including the Pedi, Sotho, Venda and Shona.

In Shona, the language spoken in Zimbabwe, the word mapungu is the plural form of the word chapungu, denoting the bateleur eagle, which is widely believed to be the model for the Zimbabwean birds that once graced the massive Great Zimbabwe royal complex. The ending "bwe" is a diminutive of the word "ibwe," which means stone or rock in Shona language. Mapungubwe, in this respect, means the 'rocks of the bateleur eagles'—an indication that there were many bateleurs in the area or location. Chapungu Village in Harare, Zimbabwe's capital, which showcases the country's arts and sculpture traditions, is a tribute to the spirit of the bateleur, a bird which has deep religious connotations in Shona culture.The word Mapungubwe may also have originated from the Shona word mhungu which means black mamba, the plural of mhungu is mapungu. Mapungubwe is then a diminutive for ibwe re mapungu which refers to a rocky area where the black mamba snakes are a common sight. It is not uncommon practice in Zimbabwe to shorten phrases with a solid word as is the case with the name Zimbabwe itself which was diminished from dzimba dzemabwe(house of stone), Great Zimbabwe. These rocky places are found throughout Zimbabwe, in Chikomba district under Chief Chandiwana there exists one of the imposing rocky plateaus called Maringobwe which refers to ibwe remaringo. Kuringa is a verb which means to look in the Zezuru dialect of the Shona people. This suggests the elevated place may have been used for surveillance of the surrounding areas, numerous rock paintings credited to the nomadic hunter gatherer bushmen or Khoisan who roamed the area before Bantu migration are a common sight.

Culture and society

Mapungubwean society is thought by archaeologists to be the first class-based social system in southern Africa; that is, its leaders were separated from and higher in rank than its inhabitants. Thovhele Shiriyadenga Nemapungubwe was the king (Thovhele in Venda) of Mapungubwe. He later divided his state into districts that were then given and ruled by his children who then became Paramount Chiefs, who had to report to the king himself. Mapungubwe's architecture and spatial arrangement also provide "the earliest evidence for sacred leadership in southern Africa".[8]

Life in Mapungubwe was centred on family and farming. Special sites were created for initiation ceremonies, household activities, and other social functions. Cattle lived in kraals located close to the residents' houses, signifying their value.

Most speculation about society continues to be based upon the remains of buildings, since the Mapungubweans left no written record.

The kingdom was likely divided into a three-tiered hierarchy with the commoners inhabiting low-lying sites, district leaders occupying small hilltops, and the capital at Mapungubwe hill as the supreme authority.[6] Elites within the kingdom were buried in hills. Royal wives lived in their own area away from the king. Important men maintained prestigious homes on the outskirts of the capital. This type of spatial division occurred first at Mapungubwe but would be replicated in later Butua and Rozwi states.[5] The growth in population at Mapungubwe may have led to full-time specialists in ceramics, specifically pottery. Gold objects were uncovered in elite burials on the royal hill (Mapungubwe hill).[6]

Re-discovery

On New Year's Eve 1932, ESJ van Graan, a local farmer and prospector, and his son, a former student of the University of Pretoria, set out to follow up on a legend he had heard about.

According to an article published in 1985, translated from the Afrikaans text: Remains of a Rock Fort located on top of the hill were under investigation, dated back to the 11th century. The Archeological site is closed to the public, except for supervised visits and tours. However some of the items discovered were on display at the Department of Archeology, at the University of Pretoria. Mapungubwe Hill and K2 were declared national monuments in the 1980s by the government.[9] Two years later Muhammad Muaaz Vawda discovered a grave.

Burials at Mapungubwe Hill

At least twenty four skeletons were unearthed on Mapungubwe hill but only eleven were available for analysis, with the rest disintegrating upon touch or as soon as they were exposed to light and air. Most of the skeletal remains were buried with few or no accessories with most adults buried with glass beads. Two adult burials (labeled numbers 10 and 14 by the early excavators) as well as one unlabelled skeleton (referred to as the original gold burial)[10] were associated with gold artefacts and were unearthed from the so-called grave area upon Mapungubwe hill. Recent genetic studies found these first two skeletons to be of Khoi/San descent and thought to be a king and queen of Mapungubwe. Despite this latest information the remains were all buried in the traditional Bantu burial position (sitting with legs drawn to the chest, arms folded round the front of the knees) and they were facing west. The Skeleton numbered 10, a male, was buried with his hand grasping the golden Scepter.

The skeleton labelled number 14 (female) was buried with at least 100 gold wire bangles around her ankles and there were at least one thousand gold beads in her grave. The last gold burial (male), who was most probably the King, was buried with a headrest and three objects made of gold foil tacked onto a wooden core, depicting a bowl, scepter and rhino. At least two more rhino were in the sample, but their association with a specific grave is unknown.

In 2007, the South African Government gave the green light for the skeletal remains that were excavated back in 1933 to be reburied on Mapungubwe hill in a ceremony that took place on 20 November 2007.

The Mapungubwe Landscape was declared a World Heritage Site on 3 July 2003.

Mapungubwe National Park

The area is now part of Mapungubwe National Park, which with the Tuli Block (Botswana) and the Tuli Safari area (Zimbabwe), forms part of the Limpopo-Shashe Transfrontier Conservation Area, now officially known as Greater Mapungubwe Transfrontier Conservation Area.

Entrance to Mapungubwe National Park, Limpopo Province, South Africa

Entrance to Mapungubwe National Park, Limpopo Province, South Africa Taken from South Africa, to the left is Botswana and Zimbabwe is on the right. The river running from left to right is the Limpopo River. The river which disappears on the horizon is the Shashe

Taken from South Africa, to the left is Botswana and Zimbabwe is on the right. The river running from left to right is the Limpopo River. The river which disappears on the horizon is the Shashe Sandstone rock formations typical of Mapungubwe National Park

Sandstone rock formations typical of Mapungubwe National Park Treetop Boardwalk. All facilities at Mapungubwe National Park are wheelchair-friendly.

Treetop Boardwalk. All facilities at Mapungubwe National Park are wheelchair-friendly. Mapungubwe Hill viewed from the north

Mapungubwe Hill viewed from the north An archaeological excavation site at Mapungubwe.

An archaeological excavation site at Mapungubwe.

See also

Notes

- ↑ http://www.sahistory.org.za/article/mapungubwe

- ↑ Hrbek, page 322

- ↑ Hrbek, page 323

- ↑ Hrbek, page 326

- 1 2 3 Hrbek, page 324

- 1 2 3 4 Hrbek, page 325

- ↑ "9/2/240/0001 - Mapungubwe Archaeological Site, Greefswald, Messina District". South African Heritage Resources Agency. Archived from the original on 19 August 2013. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- ↑ Origin of Species and Evolution, Wits University Showcase

- ↑ "Mapungubwe National Park and World Heritage Site: History of the Park". SANParks. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- ↑ A. Duffey 2012. Mapungubwe: Interpretation of the Gold Content of the Original Gold Burial M1, A620. Journal of African Archaeology 10 (2), 2012, pages 175–187.

References

- Fouché, L. (1937). Mapungubwe: Ancient Bantu Civilisation on the Limpopo. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 183 pages.

- Gardner, G.A. (1949). "Hottentot Culture on the Limpopo". South African Archeological Journal. 4 (16): 116–121.

- Gardner, G.A. (1955). "Mapungubwe: 1935 – 1940". South African Archeological Journal. 10 (39): 73–77.

- Hall, Martin; Rebecca Stefoff (2006). Great Zimbabwe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 48 pages. ISBN 0-19-515773-7.

- Hrbek, Ivan; Fasi, Muhammad (1988). Africa from the Seventh to the Eleventh Century. London: Unesco. pp. 869 pages. ISBN 92-3-101709-8.

- Walton, J. (1956). "Mapungubwe and Bambandyanalo". South African Archeological Journal. 11 (41): 27.

- Walton, J. (1956). "Mapungubwe and Bambandyanalo". South African Archeological Journal. 11 (44): 111.

- Duffey, Sian Tiley-Nel et al. The Art and Heritage Collections of the University of Pretoria.Univ. of Pretoria, 2008.