MCR-1

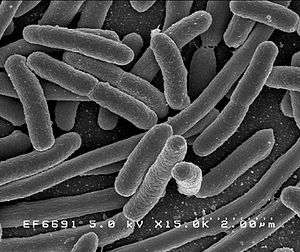

The mobilized colistin resistance (mcr-1) gene confers plasmid-mediated resistance to colistin, one of a number of last-resort antibiotics for treating gram negative infections. mcr-1 is capable of horizontal transfer between different strains of a bacterial species and after discovery in November 2015 in E. coli (strain SHP45) from a pig in China it has been found in Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica, Klebsiella pneumonia, Enterobacter aerogenes, and Enterobacter cloacae. As of 2017, it has been detected in more than 30 countries on 5 continents in less than a year.

Description

The "mobilized colistin resistance"(mcr-1) gene confers plasmid-mediated resistance to colistin, a polymyxin and one of a number of last-resort antibiotics for treating infections.[1][2] The gene is found in no less than ten species of the Enterobacteriaceae: Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Klebsiella pneumonia, Enterobacter aerogenes, Enterobacter cloacae, Chronobacter sakazakii, Shigella sonnei, Kluyvera species, Citrobacter species, and Raoultella ornithinolytica. The mcr-2 gene is a rare variant of mcr-1 and is found only in Belgium. Additional variants, mcr-3, mcr-4, and mcr-5, were identified in E. coli and Salmonella.[3]

mcr-1 is the first polymyxin resistance gene known to be capable of horizontal transfer between different strains of a bacterial species.[1]

The mechanism of resistance of the MCR gene is a phosphatidylethanolamine transferase. The enzyme transfers a phosphoethanolamine residue to the lipid A present in the cell membrane of gram-negative bacteria. The altered lipid A has much lower affinity for colistin and related polymyxins resulting in reduced activity of the antimicrobial. This type of resistance is known as target modification.[4]

Discovery and geographical spread

The gene was first discovered in E. coli (strain SHP45) from a pig in China April 2011 and published in November 2015.[5][6] It was identified by independent researchers in human samples from Malaysia, China,[1] England,[7][8] Scotland,[9] and the United States.[10]

In April 2016, a 49-year-old woman sought medical care at a Pennsylvania clinic for UTI symptoms. PCR of an E. coli isolate cultured from her urine revealed the mcr-1 gene for the first time in the United States,[11] and the CDC sent an alert to health care facilities. In the following twelve months, four additional people were reported to have infections with mcr-1 carrying bacteria.[12]

As of February 2017 mcr-1 has been detected in more than 30 countries on 5 continents in less than a year,[13] and it appears to be spreading in hospitals in China.[14] The prevalence in five Chinese provinces between April 2011 and November 2014 was 15% in raw meat samples and 21% in food animals during 2011–14, and 1% in people hospitalized with infection.[1]

Origins

Using genetic analysis, researchers believe that they have shown that the origins of the gene were on a Chinese pig farm where colistin was routinely used.[15][16]

Inhibition

Given the importance of mcr-1 in enabling bacteria to acquire polymyxin resistance, MCR-1 (the protein that is encoded by mcr-1) is a current inhibition target for the development of new antibiotics.[17] For example, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, a metal-chelating agent, was shown to inhibit MCR-1 as it is a zinc-dependent enzyme.[4] Substrate analogues, such as ethanolamine and glucose, were also shown to inhibit MCR-1.[18] The use of a combined antibiotics regime has shown to be able to overcome the resistance that is caused by mcr-1, although the mechanism of action may not be directly targeting the MCR-1 protein.[19]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Liu YY, Wang Y, Walsh TR, Yi LX, Zhang R, Spencer J, et al. (18 November 2015). "Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study". Lancet Infect Dis. 16: 161–8. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7. PMID 26603172.

- ↑ Reardon, Sara (21 December 2015). "Spread of antibiotic-resistance gene does not spell bacterial apocalypse — yet". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2015.19037.

- ↑ Sun J, Zhang H, Liu YH, Feng Y (March 2018). "Towards Understanding MCR-like Colistin Resistance". Trends in Microbiology. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2018.02.006. PMID 29525421.

- 1 2 Hinchliffe, Philip; Yang, Qiu E.; Portal, Edward; Young, Tom; Li, Hui; Tooke, Catherine L.; et al. (2017). "Insights into the Mechanistic Basis of Plasmid-Mediated Colistin Resistance from Crystal Structures of the Catalytic Domain of MCR-1". Scientific Reports. 7: 39392. doi:10.1038/srep39392. ISSN 2045-2322.

- ↑ "Newly Reported Gene, mcr-1, Threatens Last-Resort Antibiotics". Antibiotic/Antimicrobial Resistance: AR Solutions in Action. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 30 November 2016.

- ↑ Gao R, Hu Y, Li Z, Sun J, Wang Q, Lin J, Ye H, Liu F, Srinivas S, Li D, Zhu B, Liu YH, Tian GB, Feng Y (28 November 2016). "Dissemination and Mechanism for the MCR-1 Colistin Resistance". PLOS Pathogens. 12 (11): e1005957. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1005957. PMC 5125707. PMID 27893854.

- ↑ Schnirring, Lisa (18 December 2015). "More MCR-1 findings lead to calls to ban ag use of colistin". CIDRAP News. CIDRAP — Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy. Retrieved 2015-12-22.

- ↑ McKenna, Maryn. "Apocalypse Pig Redux: Last-Resort Resistance in Europe". Phenomena. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ↑ "Antibiotic-resistant bacteria detected in Scotland". BBC News. 2016-08-03. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- ↑ The U.S. Military HIV Research Program (MHRP). "First discovery in United States of colistin resistance in a human E. coli infection". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2016-05-27.

- ↑ Wappes, Jim (26 May 2016). "Highly resistant MCR-1 'superbug' found in US for first time". CIDRAP News. CIDRAP — Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy. Retrieved 2016-08-09.

- ↑ "Tracking mcr-1". Antibiotic/Antimicrobial Resistance: Biggest Threats. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 24 February 2017.

- ↑ Yi L, Wang J, Gao Y, Liu Y, Doi Y, Wu R, Zeng Z, Liang Z, Liu JH (2017). "mcr-1-Harboring Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium Sequence Type 34 in Pigs, China". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 23 (2): 291–295. doi:10.3201/eid2302.161543. PMC 5324782. PMID 28098547.

- ↑ Dall, Chris (27 January 2017). "Studies show spread of MCR-1 gene in China". CIDRAP News. CIDRAP — Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy.

- ↑ Nield, David. "A Dangerous Antibiotic-Resistant Gene Has Spread The World. We Now Know Where It Started". ScienceAlert. Retrieved 2018-04-02.

- ↑ Wang, Ruobing; Dorp, Lucy; Shaw, Liam P.; Bradley, Phelim; Wang, Qi; Wang, Xiaojuan; Jin, Longyang; Zhang, Qing; Liu, Yuqing (2018-03-21). "The global distribution and spread of the mobilized colistin resistance gene mcr-1". Nature Communications. 9 (1). doi:10.1038/s41467-018-03205-z. ISSN 2041-1723.

- ↑ Son, Soo Jung; Huang, Renjie; Squire, Christopher J.; Leung, Ivanhoe K. H. (2018). "MCR-1: a promising target for structure-based design of inhibitors to tackle polymyxin resistance". Drug Discovery Today. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2018.07.004. PMID 30036574.

- ↑ Wei, Pengcheng; Song, Guangji; Shi, Mengyang; Zhou, Yafei; Liu, Yang; Lei, Jun; Chen, Peng; Yin, Lei (2018). "Substrate analog interaction with MCR-1 offers insight into the rising threat of the plasmid-mediated transferable colistin resistance". FASEB Journal. 32: 1085–1098. doi:10.1096/fj.201700705R. PMID 29079699.

- ↑ MacNair, Craig R.; Stokes, Jonathan M.; Carfrae, Lindsey A.; Fiebig-Comyn, Aline A.; Coombes, Brian K.; Mulvey, Michael R.; Brown, Eric D. (2018). "Overcoming mcr-1 mediated colistin resistance with colistin in combination with other antibiotics". Nature Communications. 9: 458. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-02875-z. PMC 5792607. PMID 29386620.