Little Free Library

A Little Free Library | |

| Founded | 2009 |

|---|---|

| Founder | Todd Bol[1] |

| Type | 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization[2] |

| 45-4043708[3] | |

| Headquarters | Hudson, Wisconsin |

| Coordinates | 44°59′31″N 92°41′11″W / 44.9920°N 92.6863°WCoordinates: 44°59′31″N 92°41′11″W / 44.9920°N 92.6863°W |

| Todd Bol[4] | |

| Monnie McMahon[4] | |

Revenue (2015) | $729,567[3] |

| Expenses (2015) | $820,893[3] |

Employees (2015) | 14[3] |

Volunteers (2015) | 24,000[3] |

| Website |

littlefreelibrary |

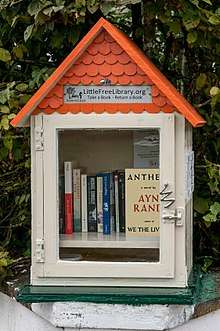

Little Free Library is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization[2] that aims to inspire a love of reading, build community, and spark creativity by fostering neighborhood book exchanges around the world. More than 60,000 public bookcases are registered with the organization and branded as Little Free Libraries. Through Little Free Libraries, present in all 50 of the United States and over 80 countries, millions of books are exchanged each year, with the aim of increasing access to books for readers of all ages and backgrounds. The Little Free Library nonprofit is based in Hudson, Wisconsin, United States.[5]

History

The first Little Free Library was built in 2009 by Todd Bol in Hudson, Wisconsin. He mounted a wooden container designed to look like a one-room schoolhouse on a post on his lawn and filled it with books as a tribute to his mother, who was a book lover and school teacher. Bol shared his idea with his partner, Rick Brooks, and the idea spread rapidly, soon becoming a "global sensation".[6] Little Free Library officially incorporated on May 16, 2012,[7] and the Internal Revenue Service recognized Little Free Library as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization in the same year.[8][9]

The original goal was the creation of 2,150 Little Libraries, which would surpass the number of libraries founded by Andrew Carnegie. As of November 2016, there were 50,000 registered Little Free Libraries worldwide.[10]

The Little Free Library nonprofit has been honored by the National Book Foundation, the Library of Congress, Library Journal, and others for its work promoting literacy and a love of reading.[11]

Margret Aldrich wrote The Little Free Library Book to chronicle the movement.[12]

The Little Free Library organization has used funds raised to donate book exchanges and create a reading program called the Action Book Club.[13][14]

How Little Free Libraries work

Like other public bookcases, anyone passing by can take a book to read or leave one for someone else to find. The organization relies on volunteers, known as stewards, to construct, install, and maintain book exchange boxes. For a book exchange box to be registered and legally use the Little Free Library brand name, stewards must purchase a Library box kit or a charter sign.[15] This sign reads Little Free Library and displays an official charter number.[16][17]

Registered Little Free Libraries are eligible to be featured on the Little Free Library World Map,[18] which lists locations with GPS coordinates and other information. Little Free Libraries are located around the world, although the majority are located in the United States.

Little Free Libraries of all shapes and sizes exist, from small, brightly painted wooden houses to a larger library based on Doctor Who's TARDIS.[19][20]

Zoning

Little Free Libraries are typically welcomed by communities; if zoning problems arise, however, local governments often work with residents to find solutions. In late 2012, the village of Whitefish Bay, Wisconsin, denied permission to potential Little Free Library projects and required that an existing Little Free Library be removed because of a village ordinance that prohibited structures in front yards. Village trustees also worried about inappropriate material being placed in the boxes.[21] However, in August 2013, the village approved a new ordinance that specifically allowed Little Free Library boxes to be put up on private property.[22]

In June 2014, city officials in Leawood, Kansas shut down a Little Free Library under a city ordinance prohibiting detached structures.[23] The family of the nine-year-old boy who built the structure created a Facebook page to support the amendment of Leawood's city code.[24] Another resident of the city who erected a Little Free Library was threatened with a $25 fine.[25] In July, the city council unanimously approved a temporary moratorium to permit Little Free Libraries on private property.[26]

On January 29, 2015, the Metropolitan Planning Commission in Shreveport, Louisiana shut down a Little Free Library. Zoning administrator Alan Clarke said that city ordinances only permitted libraries in commercial zones and that the one that was shut down had “bothered someone.”[27] The following month, the city council temporarily legalized book exchange boxes until the zoning ordinances could be amended to permanently allow them.[28]

See also

- Public bookcase for history and generic aspects of the phenomenon

References

- ↑ Durst, Kristen (7 March 2012). "'Little Free Libraries' Hope For Lending Revolution". All Things Considered. National Public Radio. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- 1 2 "Little Free Library Ltd." Exempt Organizations Select Check. Internal Revenue Service. Retrieved May 10, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax". Little Free Library Ltd. Guidestar. December 31, 2015.

- 1 2 "People of Little Free Library". Little Free Library. Retrieved May 10, 2017.

- ↑ "About Little Free Library | Little Free Library". littlefreelibrary.org. Retrieved 2017-02-27.

- ↑ "Little Free Library: What People Are Saying" (PDF). Retrieved February 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Little Free Library, Ltd." Corporate Records. Wisconsin Department of Financial Institutions. Retrieved May 11, 2017.

- ↑ "Little Free Library Ltd". Guidestar. Retrieved May 11, 2017.

- ↑ "History of Little Free Library". Little Free Library. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ↑ Aldrich, Margaret. "Big Little Milestone: There Are Now 50,000 Little Free Libraries Worldwide". Book Riot. November 7, 2016. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ↑ "Little Free Library Milestones". Little Free Library. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ↑ Aldrich, Margaret. The Little Free Library Book. Coffee House Press. ISBN 978-1566894074. April 14, 2015.

- ↑ https://littlefreelibrary.org/impact-about/

- ↑ https://littlefreelibrary.org/actionbookclub/

- ↑ https://littlefreelibrary.org/registration-process/

- ↑ Karnowski, Steve. "Wis. Man's Little Free Library Copied Worldwide". Associated Press. Yahoo! News. December 25, 2012.

- ↑ NBC nightly News Archived 2012-05-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Little Free Library World Map". Little Free Library via Google Maps. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ↑ Turner, Brodie. "Little Free Library: How a Loving Tribute Became a Worldwide Sensation". Good News Shared. Retrieved February 22, 2015.

- ↑ Ford, Dick. "The Mize Tardis". Mize City Library (Mize, Mississippi). Instagram. January 4, 2016.

- ↑ Stingl, Jim (10 November 2012). "Village slaps endnote on Little Libraries". Wisconsin Journal Sentinel. Madison, Wisc. Archived from the original on 2013-03-08. Retrieved November 12, 2012.

- ↑ "News & Notes: Aug. 7". Whitefish Bay Now. 7 August 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- ↑ Waxman, Olivia B. (20 June 2014). "City Forces 9-Year-Old Boy to Move 'Little Free Library' From Front Yard". Time.

- ↑ "Spencer's Little Free Library". Facebook. 19 June 2014.

- ↑ McCallister, Laura; Fowler, Brix (18 June 2014). "City to fine owners of Little Free Libraries". KFVS-TV.

- ↑ Baumann, Caroline (7 July 2014). "'Little Free Libraries' legal in Leawood thanks to 9-year-old Spencer Collins". Kansas City Star (updated 8 July 2014).

- ↑ Burris, Alexandria (30 January 2015). "Other Little Free Libraries could be ordered to cease". Shreveport Times.

- ↑ Burris, Alexandria (10 February 2015). "Little Free Libraries made legal — for now". Shreveport Times.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Little Free Library. |