List of Major League Baseball perfect games

Over the 140 years of Major League Baseball history, and over 210,000 games played,[1] there have been 23 official perfect games by the current definition. No pitcher has ever thrown more than one. The perfect game thrown by Don Larsen in game 5 of the 1956 World Series is the only postseason perfect game in major league history and one of only two postseason no-hitters. The first two major league perfect games, and the only two of the premodern era, were thrown in 1880, five days apart. The most recent perfect game was thrown on August 15, 2012, by Félix Hernández of the Seattle Mariners. There were three perfect games in 2012; the only other year of the modern era in which as many as two were thrown was 2010. By contrast, there have been spans of 23 and 33 consecutive seasons in which not a single perfect game was thrown. Though two perfect-game bids have gone into extra innings, no extra-inning game has ever been completed to perfection.

The first two pitchers to accomplish the feat did so under rules that differed in many important respects from those of today's game: in 1880, for example, only underhand pitching—from a flat, marked-out box 45 feet from home plate—was allowed, it took eight balls to draw a walk, and a batter was not awarded first base if hit by a pitch.[2] Lee Richmond, a left-handed pitcher for the Worcester Ruby Legs, threw the first perfect game. He played professional baseball for six years and pitched full-time for only three, finishing with a losing record. The second perfect game was thrown by John Montgomery Ward for the Providence Grays. Ward, an excellent pitcher who became an excellent position player, went on to be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Though convention has it that the modern era of Major League Baseball begins in 1900, the essential rules of the modern game were in place by the 1893 season. That year the pitching distance was moved back to 60 feet, 6 inches, where it remains, and the pitcher's box was replaced by a rubber slab against which the pitcher was required to place his rear foot. Two other crucial rules changes had been made in recent years: In 1887, the rule awarding a hit batsman first base was instituted in the National League (this had been the rule in the American Association since 1884: first by the umpire's judgment of the impact; as of the following year, virtually automatically).[3] In 1889, the number of balls required for a walk was reduced to four.[4] Thus, from 1893 on, pitchers sought perfection in a game whose most important rules are the same as today, with two significant exceptions: counting a foul ball as a first or second strike, enforced by the National League as of 1901 and by the American League two years later, and the use of the designated hitter in American League games since the 1973 season.[5]

During baseball's modern era, 21 pitchers have thrown perfect games. Most were accomplished major leaguers. Six have been inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame: Cy Young, Addie Joss, Jim Bunning, Sandy Koufax, Catfish Hunter, and Randy Johnson. Roy Halladay won two Cy Young Awards and was named to eight All-Star teams. David Cone won the Cy Young once and was named to five All-Star teams. Félix Hernández is likewise a one-time Cy Young winner, as well as a six-time All-Star. Four other perfect-game throwers, Dennis Martínez, Kenny Rogers, David Wells and Mark Buehrle, each won over 200 major league games. Matt Cain, though he ended with a 104–118 record, was a three-time All-Star, played a pivotal role on two World Series–winning teams, and twice finished top ten in Cy Young voting. For a few, the perfect game was the highlight of an otherwise unremarkable career. Mike Witt and Tom Browning were solid major league pitchers; Browning was a one-time All-Star with a career record of 123–90, while Witt was a two-time All-Star, going 117–116. Larsen, Charlie Robertson, and Len Barker were journeyman pitchers—each finished his major-league career with a losing record; Barker made one All-Star team, Larsen and Robertson none. Dallas Braden retired with a 26–36 record after five seasons due to a shoulder injury. Philip Humber's perfect game was the only complete game he ever recorded, and his major league career, in which he went 16–23, ended the year after he threw it.

Major League Baseball perfect games

19th century

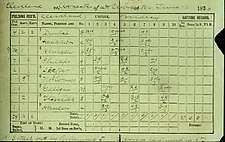

| Pitcher | Date | Game |

|---|---|---|

| Lee Richmond (Wor) LHP, 23 5 K | June 12, 1880 |

|

| John Montgomery Ward (Prov) RHP, 20 5 K | June 17, 1880 |

|

Lee Richmond

Richmond was pitching in his first full season in the big leagues after appearing in one game in 1879. He was apparently considered a good hitter, as he batted second in the lineup. His perfect game featured an unusual 9–3 putout, with Worcester right fielder Lon Knight throwing out Cleveland's Bill Phillips at first.[6] The play came on one of three balls Cleveland hit out of the infield.[7] Three outs were recorded on "foul bounds": balls caught after bouncing once in foul territory (the foul bound rule was eliminated three years later). In the seventh inning, the game was delayed for seven minutes due to rain; Richmond dried the ball off with sawdust when he returned to the mound.[8] A monument marks the site of the Worcester Agricultural Fairgrounds where the game took place, now part of the campus of Becker College.[9] The feat was recognized as unusual: a newspaper report described it as "the most wonderful game on record".[10][11]

John Montgomery Ward

Monte Ward threw his perfect game at the Grays' park in Providence, but Buffalo, by virtue of a coin toss, which was the custom under the rules at that time, was officially the "home" team, batting in the bottom of each inning. At the age of 20 years, 105 days, Ward is the youngest pitcher ever to throw a perfect game. He batted sixth in the lineup. Beginning in 1881, the year after his perfect game, Ward spent more time as a position player than a pitcher; in 1885, following an arm injury, he became a full-time infielder.[12] The five days between Ward's game and Richmond's is the shortest amount of time between major-league perfect games.

Modern era

| Pitcher | Date | Game |

|---|---|---|

| Cy Young (BOS) RHP, 37 8 K | May 5, 1904 |

|

| Addie Joss (CLE) RHP, 28 74 pitches, 3 K | October 2, 1908 |

|

| Charlie Robertson (CHW) RHP, 26 90 pitches, 6 K | April 30, 1922 |

|

| Don Larsen (NYY) RHP, 27 97 pitches, 7 K | October 8, 1956 |

|

| Jim Bunning (PHI) RHP, 32 90 pitches, 10 K | June 21, 1964 |

|

| Sandy Koufax (LAD) LHP, 29 113 pitches, 14 K | September 9, 1965 |

|

| Catfish Hunter (OAK) RHP, 22 107 pitches, 11 K | May 8, 1968 |

|

| Len Barker (CLE) RHP, 25 103 pitches, 11 K | May 15, 1981 |

|

| Mike Witt (CAL) RHP, 24 94 pitches, 10 K | September 30, 1984 |

|

| Tom Browning (CIN) LHP, 28 100 pitches, 7 K | September 16, 1988 |

|

| Dennis Martínez (MON) RHP, 36 95 pitches, 5 K | July 28, 1991 |

|

| Kenny Rogers (TEX) LHP, 29 98 pitches, 8 K | July 28, 1994 |

|

| David Wells (NYY) LHP, 34 120 pitches, 11 K | May 17, 1998 |

|

| David Cone (NYY) RHP, 36 88 pitches, 10 K | July 18, 1999 |

|

| Randy Johnson (ARI) LHP, 40 117 pitches, 13 K | May 18, 2004 |

|

| Mark Buehrle (CHW) LHP, 30 116 pitches, 6 K | July 23, 2009 |

|

| Dallas Braden (OAK) LHP, 26 109 pitches, 6 K | May 9, 2010 |

|

| Roy Halladay (PHI) RHP, 34 115 pitches, 11 K | May 29, 2010 |

|

| Philip Humber (CHW) RHP, 29 96 pitches, 9 K | April 21, 2012 |

|

| Matt Cain (SF) RHP, 27 125 pitches, 14 K | June 13, 2012 |

|

| Félix Hernández (SEA) RHP, 26 113 pitches, 12 K | August 15, 2012 |

|

Cy Young

Young's perfect game was part of a hitless streak of 24 or 25⅓ straight innings—depending on whether partial innings at either end of the streak are included. In either calculation, the streak remains a record. It was also part of a streak of 45 straight innings in which Young did not give up a run, which was then a record.[13]

Addie Joss

Joss's was the most pressure-packed of any regular-season perfect game. With just four games left on their schedule, the Cleveland Naps were involved in a three-way pennant race with the Tigers and the White Sox, that day's opponents. Joss's counterpart, Ed Walsh, struck out 15 and gave up just four scattered singles. The lone, unearned run scored as a result of a botched pickoff play and a wild pitch.[15] The Naps ended the day tied with the Tigers for first, with the White Sox two games back; the Tigers won the league by a half game over the Naps. Joss threw a second no-hitter against the White Sox in 1910, making him and Tim Lincecum of the San Francisco Giants the only major league pitchers ever to throw two no-hitters against the same team.

Charlie Robertson

Robertson's perfect game was only his fifth appearance, and fourth start, in the big leagues. He finished his career with a 49–80 record, the fewest wins of any perfect-game pitcher until Dallas Braden; Robertson's winning percentage of .380 remains the lowest of anyone who ever threw a perfect game. The Tigers, led by player-manager Ty Cobb, accused Robertson of illegally doctoring the ball with oil or grease.[16] In terms of the opposing team's ability to get on base, this is statistically the most unlikely of perfectos: the 1922 Tigers had an on-base percentage (OBP) of .373.[17]

Don Larsen

Larsen did not know he would pitch in Game 5 of the 1956 World Series until a few hours before game time.[18] This was his second start of the Series; he had lasted less than two innings in Game 2. In his perfect game, Larsen employed the style he had adopted in mid-season, working without a windup. Just one Dodgers batter—Pee Wee Reese, in the first inning—worked a three-ball count.[19] The Dodgers had the highest season winning percentage of any team ever to lose a perfect game: .604. The image of catcher Yogi Berra leaping into Larsen's arms after the final strike is one of the most famous in baseball history.[20] The 34 years between Robertson's feat and Larsen's is the longest gap between perfect games.

Jim Bunning

Bunning's perfect game, pitched on Father's Day, was the first in the National League since Ward's 84 years before. Defying the baseball superstition that holds one should not talk about a no-hitter in progress, Bunning spoke to his teammates about the perfect game as it developed to loosen them up and relieve the pressure.[21]

Sandy Koufax

Koufax's perfect game was the first one pitched at night. It was nearly a double no-hitter, as Cubs pitcher Bob Hendley gave up only one hit, a bloop double to left-fielder Lou Johnson in the seventh inning that did not figure in the scoring. The Dodgers scored their only run in the fifth inning: Lou Johnson reached first on a walk, advanced to second on a sacrifice bunt, stole third, and scored when Cubs catcher Chris Krug overthrew third base on the play. The game also set records for the fewest hits by both teams, one, and the fewest base runners by both teams, two (both Johnson). Koufax's 14 strikeouts are tied with Matt Cain for the most ever thrown by a perfect game pitcher.

Catfish Hunter

Hunter, a talented batter, was also the hitting star of his perfect game. He went 3 for 4 with a double and 3 RBIs, including a bunt single that drove home the first and thus winning run in the seventh inning—easily the best offensive performance ever by a perfect game pitcher. At 22 years and 30 days old, Hunter was the youngest pitcher to throw a perfect game in the modern era. This was the first no-hitter of the Athletics' Oakland tenure, which was only 25 games old.[22]

Len Barker

Barker's perfect game was the first one in which designated hitters were used. He did not reach a three-ball count in the entire game.[23] Toronto shortstop Alfredo Griffin, who played for the losing team in this game, went on to play for the losers in the perfect games of Browning and Martínez. Also on the losing end of this game was Danny Ainge, who played 14 seasons in the National Basketball Association. All 11 of Barker's strikeouts were swinging.[24]

Mike Witt

Witt's perfect game came on the last day of the 1984 season. Reggie Jackson, who drove in the only run of the game on a seventh-inning fielder's choice ground ball, was also on the winning team in Catfish Hunter's perfect game. On April 11, 1990, Witt, pitching out of the bullpen, combined with starting pitcher Mark Langston to throw a no-hitter for the California Angels.

Tom Browning

Browning's perfect game, for the Cincinnati Reds against the Los Angeles Dodgers in September 1988, came against the team that eventually won that year's World Series, the only time that has happened. A two-hour, twenty-seven-minute rain delay[25] caused the game to start at approximately 10 PM. Right fielder Paul O'Neill, who played for the winning side in this game, also played for the winning side in the perfect games of Wells and Cone. The following July 4, Browning came within an inning of becoming the first pitcher to throw two perfect games, retiring the first 24 batters in a game against the Phillies before surrendering a leadoff double in the ninth.[26]

Dennis Martínez

Martínez, born in Granada, Nicaragua, was the first major league pitcher born outside of the United States to throw a perfect game. He achieved the feat for the Montreal Expos against the Los Angeles Dodgers in July 1991. Opposing pitcher Mike Morgan was perfect through five full innings, the latest the opposing starter in a perfect game has remained perfect. Two days earlier, Expos pitcher Mark Gardner no-hit the Dodgers through nine innings but lost the no-hitter in the tenth, meaning the Expos narrowly missed throwing a no-hitter and a perfect game in the same series. Martínez's catcher, Ron Hassey, had also caught Len Barker's perfect game. This was the third perfect game pitched against the Brooklyn/Los Angeles Dodgers, joining those of Larsen and Browning; the only other teams to lose more than one perfect game are the Twins (Hunter and Wells) and the Rays (Buehrle, Hernandez and Braden).

Kenny Rogers

Rogers benefited from center fielder Rusty Greer's fantastic diving catch of a line drive hit by Rex Hudler, leading off the ninth inning.[27] Rogers' performance against the Angels came 10 seasons after Witt's perfect game against the Rangers. The Angels and Rangers are the only major league teams to record perfect games against each other. The home plate umpire was a minor league fill-in, Ed Bean, who was working his 29th Major League game and seventh behind the plate. Bean, who was substituting for 17-year veteran Ken Kaiser, worked only seven more MLB games following Rogers' performance.

David Wells

Wells attended the same high school as Don Larsen: Point Loma High School, San Diego, California. They also both enjoyed the night life. Casey Stengel once said of Larsen, "The only thing he fears is sleep." Wells has claimed to have been "half-drunk" and suffering from a "raging, skull-rattling hangover" during his perfect game.[28] Wells' perfect game comprised the core of a streak of 38 consecutive retired batters (May 12–23, 1998), an American League record he held until 2007.

David Cone

Cone's perfect game occurred on Yogi Berra Day. Don Larsen threw out the ceremonial first pitch to Berra, who had been his catcher during the 1956 World Series perfect game. As the game wore on, television cameras showed Larsen, the only perfect game pitcher to attend another perfect game. No Expo worked even a three-ball count.[29] Cone's perfect game, which took only 88 pitches, was interrupted by a 33-minute rain delay and is the only one to date in regular-season interleague play. Following teammate Wells's perfect game the previous season, this also represents the only time two successive perfect games have been thrown by the same team.

Randy Johnson

Johnson threw his perfect game at the age of 40 years, 256 days, becoming by more than three and a half years the oldest pitcher to achieve the feat. The former holder of the mark, Cy Young, threw his at the age of 37 years, 37 days. Johnson is also the tallest perfect game pitcher at 6' 10", surpassing Mike Witt by three inches. Of the teams to have a perfect game thrown against them, the 2004 Braves have the second-highest OBP (.343) and are tied for the second-highest winning percentage (.593).[30] In contrast, the Diamondbacks had by far the worst season winning percentage (.315) of any team to benefit from a perfect game.[31]

Mark Buehrle

Buehrle was assisted by a dramatic ninth-inning wall-climbing catch by center fielder DeWayne Wise to rob Gabe Kapler of a home run; Wise had just entered the game as a defensive replacement before Kapler's at-bat. This was the first major league perfect game in which the pitcher and catcher were battery-mates for the first time; Ramón Castro had been acquired by the White Sox less than two months before.[32] This was also the first perfect game to feature a grand slam, by Josh Fields in the bottom of the second inning. Umpire Eric Cooper, who called the game, had been behind the plate for Buehrle's previous no-hitter.[33] On July 28, Buehrle followed up with another 5 2/3 perfect innings to set the major league record for consecutive batters retired at 45 (this includes the final batter he faced in his appearance before the perfect game).[34] That record was broken by Yusmeiro Petit of the San Francisco Giants in 2014[35]

Dallas Braden

Braden's perfect game, pitched on Mother's Day, was the first complete game of his career. His grandmother attended the game and celebrated on the field with him. It was the first time a perfect game had been pitched against the team with the best record in the majors at the time; coming into the contest, the Rays were 22–8.[36] The 2010 Rays are tied for the second-highest winning percentage (.593) of any team to be on the receiving end of a perfect game.[37] MLB's previous perfect game had also been thrown against the Rays, making them the second team to have successive perfect games against them (the first was the Dodgers in 1988 and 1991).[38] This game came 290 days after Buehrle's, the shortest period between modern-day perfect games—a record which lasted just three weeks, until Halladay's perfect game.

Roy Halladay

Halladay pitched the second perfect game of the 2010 season 20 days after Braden's, the shortest period between perfect games in the modern era.[39] Mark Buehrle's perfect game had been 10 months earlier, marking the first time that three perfect games occurred within a one-year span. Seven batters reached three-ball counts against Halladay.[40] Halladay nearly pitched a second perfect game in the 2010 NL Division Series against the Reds but gave up a walk to Jay Bruce. The hurler had to settle for a no-hitter and became the only perfect game pitcher to throw another no-hitter in the same season, and the fifth with two no-hitters. Halladay is the second pitcher to throw a perfect game and win the Cy Young Award in the same season; Sandy Koufax did so in 1965.[41]

Philip Humber

On April 21, 2012, Philip Humber of the Chicago White Sox pitched the third perfect game in White Sox history. The final out of Humber's perfect game came after a full-count check-swing third strike to Brendan Ryan on a ball that catcher A. J. Pierzynski dropped. As Ryan disputed umpire Brian Runge's decision that he had swung, Pierzynski threw the ball to first base for the final out.[42] As with Braden, Humber's perfect game was the first complete game of his career.[43] Humber's lifetime major league record of 16-23 gives him the fewest career wins of any pitcher who has thrown an MLB perfect game. The White Sox became the second franchise with three perfect games, joining the Yankees.

Matt Cain

On June 13, 2012, Matt Cain of the San Francisco Giants pitched the first perfect game in Giants franchise history, the second of three in 2012, and the 22nd in MLB history. Third baseman Joaquín Árias threw out Jason Castro for the final out on a chopped grounder he fielded deep behind the bag. Cain tallied 14 strikeouts, tying Sandy Koufax for the most strikeouts in a perfect game. Cain's 125 pitches are the most ever thrown in a perfect game. Cain was aided by a running catch at the wall by Melky Cabrera in the 6th and a diving catch by Gregor Blanco in the 7th. The winning Giants scored 10 runs, making this the highest-scoring perfect game. Home plate umpire Ted Barrett had also called Cone's perfect game, making him the only person to call two; having umpired at third base for Humber's game, Barrett also became just the second man, after Alfredo Griffin, to have been on the field for three perfect games—within two months; since then, there have been four more.

Félix Hernández

On August 15, 2012, Félix Hernández of the Seattle Mariners threw the 23rd perfect game in MLB history (and the first in August) against the Tampa Bay Rays. This was the first perfect game in Mariners history, and the franchise's fourth no-hitter.[44] Hernandez's performance was highlighted by 12 strikeouts and a career-high 26 swinging-strikes. In an on-field interview immediately following the last out, Hernandez said he had started thinking about the possibility of a perfect game in the second inning. It was the third time in the past four seasons that Tampa Bay was on the losing side of a perfect game. Four Rays—Evan Longoria, Carlos Peña, B.J. Upton, and Ben Zobrist—joined Alfredo Griffin in having played in three perfect games for the losing team; all four also participated in Buehrle's and Braden's.

General notes

Three perfect-game pitchers had RBIs in their games: Hunter (3), Bunning (2), and Young (1). Hunter had three hits; Richmond, Ward, Bunning, Martínez, and Cain each had one. Cain is the only pitcher to score a run during a perfect game (Gregor Blanco followed him in the order and hit a home run). Barker, Witt, Rogers, Wells, Cone, Buehrle, Braden, Humber, and Hernández did not bat in their perfect games, as the American League adopted the designated hitter rule in 1973. The latest the winning run has been scored in a perfect game is the seventh inning—this occurred in the games of Hunter (bottom), Witt (top), and Martínez (top).

Seven perfect-game pitchers have also thrown at least one additional no-hitter: Young, Joss, Bunning, Koufax, Johnson, Buehrle, and Halladay. Witt participated in a combined no-hitter. Koufax has the most total no-hitters of any perfect-game pitcher, with four. Richmond and Robertson were rookies, though each had made a single appearance in a previous season. Although by the latter part of the twentieth century, major league games were being played predominantly at night, six of the last ten perfect games, and four of the last six, have taken place in the daytime. Since 1973, nine perfect games have been thrown with the DH rule in effect (including one interleague game held at an American League park) and only five without it.

Perfect games by team

Of the thirty franchises that currently make up Major League Baseball, seven have never as of the end of the 2017 season been involved in a perfect game, win or lose, including three of the “Original 16” franchises (the Cardinals, Pirates, and Orioles) and four of the fourteen teams that joined MLB in the expansion era (the Royals, Brewers, Padres, and Rockies). The table below shows the number of perfect games won and lost by the remaining twenty-three franchises.

| Franchise | Perfect games won | Perfect games won against |

|---|---|---|

| Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim | 1 | 1 |

| Houston Astros | 0 | 1 |

| Oakland Athletics | 2 | 1 |

| Toronto Blue Jays | 0 | 1 |

| Atlanta Braves | 0 | 1 |

| Chicago Cubs | 0 | 1 |

| Arizona Diamondbacks | 1 | 0 |

| Los Angeles Dodgers | 1 | 3 |

| San Francisco Giants | 1 | 0 |

| Cleveland Indians | 2 | 0 |

| Seattle Mariners | 1 | 1 |

| Miami Marlins | 0 | 1 |

| New York Mets | 0 | 1 |

| Washington Nationals | 1 | 1 |

| Philadelphia Phillies | 2 | 0 |

| Texas Rangers | 1 | 1 |

| Tampa Bay Rays | 0 | 3 |

| Cincinnati Reds | 1 | 0 |

| Boston Red Sox | 1 | 0 |

| Detroit Tigers | 0 | 1 |

| Minnesota Twins | 0 | 2 |

| Chicago White Sox | 3 | 1 |

| New York Yankees | 3 | 0 |

Unofficial perfect games

There have been three instances in which a major league pitcher retired every player he faced over nine innings without allowing a baserunner, but, by the current definition, is not credited with a perfect game, either because there was already a baserunner when he took the mound, or because the game went into extra innings and an opposing player eventually reached base:

- On June 23, 1917, Babe Ruth, then a pitcher with the Boston Red Sox, walked the Washington Senators' first batter, Ray Morgan, on four straight pitches. Ruth, who had already been shouting at umpire Brick Owens about the quality of his calls, became even angrier and, in short order, was ejected. Enraged, Ruth charged Owens, swung at him, and had to be led off the field by a policeman. Ernie Shore came in to replace Ruth, while catcher Sam Agnew took over behind the plate for Pinch Thomas. Morgan was caught stealing by Agnew on the first pitch by Shore, who proceeded to retire the next 26 batters. All 27 outs were made while Shore was on the mound. Once recognized as a perfect game by Major League Baseball, this still counts as a combined no-hitter.[45][46]

- On May 26, 1959, Harvey Haddix of the Pittsburgh Pirates pitched what is often referred to as the greatest game in baseball history.[47] Haddix carried a perfect game through 12 innings against the Milwaukee Braves, only to have it ruined when an error by third baseman Don Hoak allowed Félix Mantilla, the leadoff batter in the bottom of the 13th inning, to reach base. A sacrifice by Eddie Mathews and an intentional walk to Hank Aaron followed; the next batter, Joe Adcock, hit a home run that became a double when he passed Aaron on the bases. Haddix and the Pirates had lost the game 1–0; despite their 12 hits in the game, they could not bring a run home. The 12 perfect innings–36 consecutive batters retired in a single game—remains a record.[48]

- On June 3, 1995, Pedro Martínez of the Montreal Expos had a perfect game through nine innings against the San Diego Padres. The Expos scored a run in the top of the tenth inning, but in the bottom, Martínez gave up a leadoff double to Bip Roberts, and was relieved by Mel Rojas, who retired the next three batters. Martínez was therefore the winning pitcher in a 1–0 Expos victory.[49]

Four other games in which one team failed to reach base are not official perfect games because they were called off before nine innings were played:[50]

- On August 11, 1907, Ed Karger of the St. Louis Cardinals pitched seven perfect innings against the Boston Braves; second game of doubleheader called by prior agreement.[50][51]

- On October 5, 1907, Rube Vickers of the Philadelphia Athletics pitched five perfect innings against the Senators; second game of doubleheader called on account of darkness. Vickers achieved his feat on the last day of the season. He also pitched the final 12 innings of the 15-inning first game.[51] His back-to-back victories were his only wins of the year.[52]

- On August 6, 1967, Dean Chance of the Minnesota Twins pitched five perfect innings against the Red Sox; game called on account of rain.[51]

- On April 21, 1984, David Palmer of the Expos pitched five perfect innings against the Cardinals; second game of doubleheader called on account of rain.[53]

On March 14, 2000, in a spring training game—by definition unofficial—the Red Sox used six pitchers to retire all 27 Toronto Blue Jays batters in a 5–0 victory. The starting pitcher for the Red Sox was Pedro Martínez (see above).[54]

Perfect games spoiled by the 27th batter

On thirteen occasions in Major League Baseball history, a perfect game has been spoiled when a batter reached base with two out in the ninth inning. Unless otherwise noted, the pitcher in question finished and won the game without allowing any more baserunners:[55]

- On July 4, 1908, Hooks Wiltse of the New York Giants hit Philadelphia Phillies pitcher George McQuillan on a 2–2 count in a scoreless game—the only time a 0–0 perfect game has been broken up by the 27th batter. Umpire Cy Rigler later admitted that he should have called the previous pitch strike 3. Wiltse pitched on, winning 1–0; his ten-inning no-hitter set a record for longest complete game no-hitter that has been tied twice but never broken.[56]

- On August 5, 1932, Tommy Bridges of the Detroit Tigers gave up a pinch-hit single to the Washington Senators' Dave Harris.[57]

- On June 27, 1958, Billy Pierce of the Chicago White Sox gave up a double, which landed just inches in fair territory, on his first pitch to Senators pinch hitter Ed Fitz Gerald.[58]

- On September 2, 1972, Milt Pappas of the Chicago Cubs walked San Diego Padres pinch hitter Larry Stahl on a borderline 3–2 pitch. Pappas finished with a no-hitter. The umpire, Bruce Froemming, was in his second year; he went on to a 37-year career in which he umpired a record 11 no-hitters. Pappas believed he had struck out Stahl, and years later continued to bear ill will toward Froemming.[59]

- On April 15, 1983, Milt Wilcox of the Tigers surrendered a pinch-hit single to the White Sox' Jerry Hairston, Sr.[60]

- On May 2, 1988, Ron Robinson of the Cincinnati Reds gave up a two-strike single to the Montreal Expos' Wallace Johnson. Robinson then allowed a two-run homer to Tim Raines and was removed from the game. The final score was 3–2, with Robinson the winner.[61] (Robinson's teammate Tom Browning threw his perfect game later that season.)

- On August 4, 1989, Dave Stieb of the Toronto Blue Jays gave up a double to the New York Yankees' Roberto Kelly, followed by an RBI single by Steve Sax. Stieb finished with a 2–1 victory.[62] This was the third time Stieb had a no-hitter broken up with two outs in the ninth inning.[63]

- On April 20, 1990, Brian Holman of the Seattle Mariners gave up a home run to Ken Phelps of the Oakland Athletics.[64][65]

- On September 2, 2001, Mike Mussina of the Yankees gave up a two-strike single to Boston Red Sox pinch hitter Carl Everett. The opposing pitcher in the game was David Cone, who had thrown the most recent perfect game two years earlier as a Yankee.[66]

- On June 2, 2010, Armando Galarraga of the Tigers was charged with a single when first-base umpire Jim Joyce incorrectly ruled Jason Donald of the Cleveland Indians safe on an infield grounder. After the game, Joyce acknowledged his mistake: "I just cost that kid a perfect game. I thought he beat the throw. I was convinced he beat the throw, until I saw the replay."[67] Tyler Kepner of the New York Times wrote that no call had been "so important and so horribly botched" since the 1985 World Series.[68] Galarraga retired the next batter as Donald advanced to third base via defensive indifference.[69] Having taken place just four days after Halladay's feat, the game would have set a new mark for proximity had it been perfect; it would also have been the third perfect game in a 25-day span. Donald was awarded first base on Galarraga's 83rd pitch, which would have made it the second most efficient perfect game on record.

- On April 2, 2013, Yu Darvish of the Texas Rangers gave up a first pitch single to Marwin González of the Astros on a ground ball between Darvish's legs and through the middle infield. Darvish was removed from the game without facing another batter, having thrown 111 pitches. With 14 strikeouts through the first 26 batters, Darvish had a chance to tie (or exceed, had he struck out González) a record for a perfect game. The Rangers won the game 7-0.

- On September 6, 2013, Yusmeiro Petit of the San Francisco Giants retired the first 26 Arizona Diamondbacks batters before giving up a single to pinch hitter Eric Chávez on a 3-2 pitch. Giants right fielder Hunter Pence dove for the ball but came up just a couple of inches short. Petit retired the next batter to finish the one-hit shutout.

- On June 20, 2015, Max Scherzer of the Washington Nationals retired the first 26 Pittsburgh Pirates batters before hitting pinch-hitter José Tábata with a pitch on a 2-2 count. It has been argued that Tábata intentionally leaned into the pitch—by rule, if "the batter makes no attempt to avoid being touched by the ball", let alone attempts to be hit by it, he is not entitled to first base. If the umpires had so ruled, the at-bat would have continued with a full count. Scherzer retired the following batter to complete the no-hitter, joining Wiltse and Pappas as only the third pitcher to do so after being denied a perfect game with two outs in the ninth.[70]

Other notable near-perfect games

Nine or more consecutive innings of perfection

There have been fifteen occasions in Major League Baseball history when a pitcher—or, in one case, multiple pitchers—recorded at least 27 consecutive outs after one or more runners reached base. In four instances, the game went into extra innings and the pitcher(s) recorded more than 27 consecutive outs:

- On May 11, 1919, Walter Johnson, pitching for the Senators against the Yankees, retired 28 batters in a row: After surrendering a one-out single in the first to Roger Peckinpaugh and then retiring the next two batters to end the inning, he was perfect in the second through the ninth. He recorded two outs in the tenth, before giving up a walk to Home Run Baker. The first Sunday game to be played legally in New York, it was ended after the 12th inning, still scoreless, because Yankee owner Jacob Ruppert mistakenly believed the new law barred play after 6 PM.[71]

- On September 24, 1919, Waite Hoyt, pitching for the Red Sox against the Yankees in the second game of a doubleheader, gave up a run in the second inning. The Red Sox tied the game in the ninth on a solo home run by Babe Ruth, his then record-breaking 28th of the season. The game report in the New York Times states, "Hoyt gave a remarkable performance of his pitching skill, and from the fourth inning to the thirteenth he did not allow a hit and not a Yankee runner reached first base. In these nine hitless innings the youngster was at the top of his form". The Yankees eventually won 2–1 when, in the 13th, Wally Pipp tripled and was brought home by a sacrifice fly. (The New York Times report states that Pipp tripled with "two out"—evidently a typographical or counting error, as the subsequent sacrifice fly, which is described in detail, would not then have been possible.)[72] Play-by-play records are not currently available for the game, but it appears that Hoyt recorded no less than 28 consecutive outs—the last out in the third inning and 27 in the perfect nine innings encompassing the fourth through the 12th.[73]

- On September 18, 1971, Rick Wise, pitching for the Phillies against the Cubs, gave up a home run to the leadoff batter in the second inning, Frank Fernández. He did not allow another baserunner until Ron Santo singled with two outs in the top of the 12th. Wise retired the next batter and the Phillies scored in the bottom of the inning, making him the winner, 4–3. Wise had been perfect for 10 2/3, retiring 32 consecutive batters—the record for most consecutive outs in a game by a winning pitcher. At the plate, Wise helped his cause by going 3 for 6, with a double and the game-winning RBI in the bottom of the 12th. The starting pitcher for the Cubs was Milt Pappas, who had his near-perfect game one year later.[74]

- On July 6, 2005, A. J. Burnett, then pitching for the Florida Marlins, surrendered a two-out single in the third inning that gave the Milwaukee Brewers a 4–1 lead. It was the fourth hit he had given up, on top of five walks. He then retired the next ten batters before leaving the game with the Marlins trailing 4–2. In his six innings, he struck out 14. Jim Mecir pitched a perfect seventh and Guillermo Mota pitched a perfect eighth and ninth as the Marlins rallied to send the game into extra innings. Todd Jones was perfect in the 10th and 11th and Valerio de los Santos picked up the win with a perfect 12th, for a total of 28 straight batters retired starting with the final batter of the third inning.[75]

In the eleven other instances, the leadoff batter (or batters) reached base in the first inning, followed by 27 consecutive batters (or batters and baserunners) being retired through the end of a nine-inning game.[76] In two cases, the leadoff baserunner was retired, meaning the pitcher faced the minimum:

- On June 30, 1908, Red Sox pitcher Cy Young walked the New York Highlanders' leadoff batter, Harry Niles, who was caught stealing. No one else reached base against Young, who also had three hits and four RBIs in Boston's 8–0 win. It was the third no-hitter of Young's career and about as close as possible to being his second perfect game.[77] He is the only pitcher in major league history to retire 27 consecutive men in a game on two separate occasions.

- On June 23, 1917, Ernie Shore of the Red Sox was on the mound when Ray Morgan, the leadoff batter, who had been walked by Babe Ruth, the previously ejected pitcher, was picked off. Shore retired the next 26 batters in succession (see "Unofficial perfect games" above).

The remaining instances in which a pitcher recorded 27 consecutive outs in a game, noting how the opponent's leadoff batter (or batters) reached base:

- May 24, 1884, Al Atkinson/Philadelphia Athletics (Pittsburgh Alleghenys' Ed Swartwood hit by pitch, stole second, reached third on a groundout, and scored on a passed ball)[78]

- May 16, 1953, Curt Simmons/Philadelphia Phillies (single by Milwaukee Braves' Bill Bruton)[79]

- May 13, 1954, Robin Roberts/Phillies (home run by Reds' Bobby Adams)[80]

- July 1, 1966, Woodie Fryman/Pittsburgh Pirates (single by New York Mets' Ron Hunt)[81]

- May 19, 1981, Jim Bibby/Pirates (single by Atlanta Braves' Terry Harper)[82]

- June 11, 1982, Jerry Reuss/Los Angeles Dodgers (double by Reds' Eddie Milner, who reached third on a sacrifice bunt and scored on a fielder's choice)[83]

- April 22, 1993, Chris Bosio/Seattle Mariners (walks by Red Sox Ernest Riles and Carlos Quintana, the latter of whom was retired on a double play)[84]

- July 7, 2006, John Lackey/Los Angeles Angels (double by Oakland Athletics' Mark Kotsay)[85]

- May 10, 2013, Shelby Miller/St. Louis Cardinals (single by Colorado Rockies' Eric Young, Jr.)[86]

No-hit, no-walk, no–hit batsman games

In Major League Baseball play since 1893, with the essential modern rules in place, there have been ten instances when a pitcher allowed not a single baserunner through his pitching efforts over a complete game of at least nine innings, but was not awarded a perfect game because of one or more fielding errors:

- On June 13, 1905, Christy Mathewson of the New York Giants pitched masterfully, but two Cubs nonetheless reached base on errors by shortstop Bill Dahlen and second baseman Billy Gilbert. In a classic pitching duel, the Cubs' Mordecai "Three Finger" Brown also carried a no-hitter into the ninth, losing it and the game, 1–0.[87]

- On September 5, 1908, the Brooklyn Dodgers' Nap Rucker blanked the Boston Doves with a flawless pitching performance, despite errors that allowed three Doves to reach base. In more than a century since, no otherwise perfect game has been spoiled by multiple errors.[88]

- On July 1, 1920, an error by Senators second baseman Bucky Harris was the lone defect in a game dominated by Walter Johnson's no-hit, no-walk, no–hit batsman effort. Harry Hooper, the Red Sox who reached base, was batting leadoff in the seventh.[89]

- On September 3, 1947, with one out in the second, Philadelphia Athletics first baseman Ferris Fain, after fielding a routine grounder, threw wildly to pitcher Bill McCahan, covering first base. Stan Spence of the Senators made it all the way to second, the only blemish on McCahan's otherwise perfect game.[90]

- On July 19, 1974, flawless through 3 2/3 innings, Cleveland Indians pitcher Dick Bosman, handling a grounder off the bat of Oakland Athletic Sal Bando, threw over the first baseman's head. Not one other Athletic reached base, making this the only occasion in major league history when the sole demerit on an otherwise perfect defensive line was the pitcher's own fielding error.[91]

- On June 27, 1980, Jerry Reuss of the Los Angeles Dodgers pitched a virtually immaculate game, but without hope of perfection—a first-inning throwing error by shortstop Bill Russell allowed the San Francisco Giants' Jack Clark to reach base. Russell atoned for his gaffe with a sharp fielding play in the eighth inning.[92]

- On August 15, 1990, Philadelphia Phillies pitcher Terry Mulholland lost his perfect-game bid in the seventh inning when the Giants' Rick Parker, batting leadoff, reached base on a throwing error by third baseman Charlie Hayes. Parker was retired when the next batter, Dave Anderson, grounded into a double play. Mulholland pitched flawlessly and faced the minimum 27 batters, but still did not qualify for a perfect game. Hayes redeemed himself for the fielding error by making a spectacular catch on a line drive in the ninth inning, protecting Mulholland's no-hitter.[93]

- On July 10, 2009, the Giants' Jonathan Sánchez pitched perfectly against the San Diego Padres through one out in the eighth inning. Third baseman Juan Uribe, who switched positions from second base to start the seventh inning, committed an error on a ground ball, his first chance at third, that allowed Chase Headley to reach first—the latest an error has resulted in the sole baserunner in an otherwise perfect game. Headley advanced to second on a wild pitch. It was the first complete game of Sánchez's career.[94]

- On June 18, 2014, reigning NL Cy Young winner Clayton Kershaw of the Dodgers threw a game against the Colorado Rockies that was perfect save for shortstop Hanley Ramírez's throwing error with no outs in the seventh inning. Kershaw's 15 strikeouts were at that point the most in a no-hit, no-walk game and his game score of 102 was the highest-ever in any no-hitter.[95]

- On October 3, 2015, Max Scherzer of the Washington Nationals surpassed both of Kershaw's marks, setting the record for a no-hit, no-walk game by striking out 17 and achieving a game score of 104 against the New York Mets. Scherzer's masterpiece, his second no-hitter of the year, was denied perfection by third baseman Yunel Escobar's sixth-inning throwing error.[96][97]

No otherwise perfect game in major league history has ever been spoiled solely by a dropped third strike, interference, or outfield error. On August 23, 2017, the Dodgers' Rich Hill had been pitching perfectly when third baseman Logan Forsythe booted a grounder by the Pirates' first batter in the bottom of the ninth inning, Jordy Mercer. It was the first time in major league history a perfect-game bid was ruined by an error in the ninth. Hill retired the next three batters, but as the Dodgers had not supported his effort with a single run (as they failed to in the top of the first extra frame, as well), Hill took his no-hit, no-walk, no–hit batsman game into the bottom of the 10th inning. The leadoff batter, Josh Harrison, became the first player ever to spoil a no-hitter with a walk-off homer in extra innings.[98][99]

See also

- List of Major League Baseball no-hitters

- Nippon Professional Baseball perfect games

- Golden set in tennis

- Maximum break in snooker

- Nine-dart finish in darts

- Perfect game in bowling

References

- ↑ Forman, Sean. "MLB's 200,000th Game". Baseball Reference. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- ↑ Nemec (2006), pp. 21–22, 85, 123.

- ↑ Dickson (2009), p. 415.

- ↑ "Baseball Rules Chronology 1845–1899". BaseballLibrary.com. Archived from the original on October 1, 2007. Retrieved August 20, 2007.

- ↑ "Baseball Rules Chronology 1900–present". BaseballLibrary.com. Archived from the original on August 26, 2014. Retrieved November 28, 2010.

- ↑ Akin, William (2003). "Bill Phillips". SABR Baseball Biography Project. Retrieved August 20, 2007.

- ↑ Hanlon (1968).

- ↑ "J. Lee Richmond's Remarkable 1879 Season"

- ↑ "Becker College: History". Becker College. Archived from the original on February 6, 2009. Retrieved June 1, 2009.

- ↑ Egan (2008), pp. 100, 295 n. 6, quotes the line within a longer passage quoted from the Cleveland Leader, June 14, 1880. Buckley (2002), p. 14, credits the Chicago Tribune with the line. Deutsch (1975), p. 14, presents a clipping from the New York Herald with the line.

- ↑ Okrent and Wulf (1989), pp. 14–15, describe a story that later emerged that Richmond hurled his historic perfecto after staying up all night following a pre-graduation dinner at Brown University, pitching in an early morning class game, and taking a train to Worcester just in time to perform his professional duties. The BaseballLibrary.com entry on Richmond Archived July 28, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. claims that a similar sequence of events preceded not his perfect game, but a game he pitched against the Chicago White Stockings on June 16. Egan (2008), p. 101, debunks the tale.

- ↑ Buckley (2002), p. 27.

- ↑ Browning (2003), pp. 145, 248.

- ↑ Coffey (2004), p. 28.

- ↑ Anderson (2000), pp. 185–186. BaseballLibrary.com Archived June 29, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. claims it was a passed ball.

- ↑ Buckley (2005), pp. 58, 61–64.

- ↑ 1922 American League Season Summary. Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved on September 16, 2010. See Coffey (2004), p. 43, for an analysis of Detroit's relatively desultory hitting at the point in the season when the game was played.

- ↑ Buckley (2002), pp. 73–74.

- ↑ Kennedy (1996).

- ↑ Lupica (1999), p. 51.

- ↑ Buckley (2002), p. vi.

- ↑ 1968 Oakland Athletics Game Log. Retrosheet. Retrieved on July 26, 2009.

- ↑ Newman (1981).

- ↑ Buckley (2002), p. 141.

- ↑ Buckley (2002), p. 169.

- ↑ "100 Most Memorable Reds Moments of the 20th Century". Cincinnati Enquirer. 1999. Retrieved June 3, 2010. Box score: July 4, 1989—Cincinnati Reds at Philadelphia Phillies Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved on June 3, 2010.

- ↑ Nightengale, Bob (July 29, 1994). "The Pitcher Is Perfect, but Greer Gets the Save". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 7, 2009. Richards, Charles (July 29, 1994). "Rogers Fires Perfect Game For Rangers; Diving Grab in 9th Saves Gem". Washington Post. Retrieved August 7, 2009.

- ↑ "Wells Claims "25 to 40 Percent" of Players Use Steroids". ESPN/Associated Press. February 27, 2003. Retrieved March 6, 2009.

- ↑ Gallagher (2003), p. 431.

- ↑ The OBP of the 2009 Rays, against which Buehrle later threw his perfect game, also rounds to .343.2004 Atlanta Braves Batting, Pitching, & Fielding Statistics. Baseball-Reference.com. 2009 Tampa Bay Rays Batting, Pitching, & Fielding Statistics. Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved on July 1, 2011.

- ↑ 2004 National League Season Summary. Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved on July 26, 2009.

- ↑ Schlegel, John (July 24, 2009). "For Buehrle, a Perfect Day for History". MLB.com. Retrieved July 24, 2009.

- ↑ Just, David (July 23, 2009). "Same Ump Called Both Buehrle No-Nos". MLB.com. Retrieved July 24, 2009.

- ↑ "Buehrle Breaks Record". ESPN.com. July 29, 2009. Retrieved July 29, 2009.

- ↑ "SB Nation". SBNation.com. August 28, 2014. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ↑ "Standings and Games on Saturday, May 8, 2010". Baseball-Reference.com. May 8, 2010. Retrieved May 9, 2010.

- ↑ 2010 American League Season Summary. Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved on October 6, 2010.

- ↑ "Braden's Perfect Game 19th Ever and Second Straight Against Rays". ESPN. Associated Press. May 9, 2010. Retrieved May 9, 2010.

- ↑ "Perfect Phillie: Halladay Pitches Perfect Game". MSNBC. May 29, 2010. Retrieved May 29, 2010.

- ↑ "Halladay's Perfect Game Is This Season's Second". ESPN/Associated Press. May 29, 2010. Retrieved May 29, 2010.

- ↑ "Second Cy Young Boosts Halladay's Hall of Fame Credentials". Sports Illustrated. November 16, 2010. Retrieved November 26, 2010.

- ↑ Caple, Jim (April 21, 2012). "Phil Humber Completes Perfect Game". MLB.com. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ↑ Powers, Scott (April 21, 2012). "Phil Humber Throws Perfect Game". ESPN.com. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ↑ Tucker, Heather (August 15, 2012). "Felix Hernandez Pitches Perfect Game". USA Today. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ↑ Vass (2002).

- ↑ Ernie Shore hastily relieves and Sam Agnew takes over behind the plate for Pinch Thomas Archived October 20, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Baseball Library. Retrieved on May 6, 2011.

- ↑ See, e.g., Chen (2009); Reisler (2007), p. 57; Thielman (2005), p. 169; Sullivan (2002), p. 139.

- ↑ Boxscore—Game Played on Tuesday, May 26, 1959 (N) at County Stadium Retrosheet. Retrieved on July 21, 2008.

- ↑ Boxscore—Game Played on Saturday, June 3, 1995 (N) at Jack Murphy Stadium Retrosheet. Retrieved on June 6, 2009.

- 1 2 Robbins (2004), p. 242.

- 1 2 3 Rothe, Emil H. The Shortened No-Hitters Baseball Research Journal. SABR. Retrieved on June 6, 2009.

- ↑ Zingg and Medeiros (1994), p. 27.

- ↑ Boxscore—Game Played on Saturday, April 21, 1984 (N) at Busch Stadium II Retrosheet. Retrieved on June 6, 2009.

- ↑ Pedro Martinez: Perfect Game—Spring Training 1918RedSox.com. Retrieved on June 6, 2009.

- ↑ See Buckley (2002) for descriptions of perfect games spoiled by the 27th batter through 2001. Note that Coffey (2004) gives incorrect years for the near-perfect games of Wiltse, Stieb, Holman, and Mussina (p. 279).

- ↑ Nemec (2006), pp. 86–87; Simon (2004), p. 54; "No Hitter Records". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved August 20, 2007. Vass (1998) notes that, as of his writing, this was one of only three otherwise perfect games where the sole lapse was a hit batsman. The pitchers in the two other cases were Lew Burdette (August 18, 1960; fifth inning) and Kevin Brown (June 10, 1997; eighth inning). Max Scherzer's June 20, 2015, game, described later in the section, is the fourth such instance.

- ↑ Deveaux (2001), p. 111; James (2003), p. 891.

- ↑ Boxscore—Game Played on Friday, June 27, 1958 (N) at Comiskey Park I Retrosheet; Billy Pierce Interview Baseball Almanac. Retrieved on June 6, 2009.

- ↑ Boxscore—Game Played on Saturday, September 2, 1972 (D) at Wrigley Field Retrosheet. Retrieved on June 6, 2009; Amspacher, Bruce (April 11, 2003). "What Really Happened? An Interview with Major League Pitching Great Milt Pappas". Professional Sports Authenticator. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved August 20, 2007. Weinbaum, William (September 20, 2007). "Froemming Draws Pappas' Ire, 35 Years Later". ESPN. Retrieved September 26, 2007.

- ↑ Boxscore—Game Played on Friday, April 15, 1983 (N) at Comiskey Park I Retrosheet. Retrieved on June 6, 2009.

- ↑ Boxscore—Game Played on Monday, May 2, 1988 (N) at Riverfront Stadium Retrosheet. Retrieved on June 6, 2009.

- ↑ Box score: August 4, 1989—New York Yankees at Toronto Blue Jays Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved on May 14, 2009.

- ↑ "David Brown, August 9, 2010. Retrieved August 9, 2010". Yahoo! Sports. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ↑ Box score: April 20, 1990—Seattle Mariners at Oakland Athletics Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved on May 14, 2009.

- ↑ Larry Stone (April 15, 2010). "Losing a perfect game was tough — but Brian Holman's been through tougher". Seattle Times. Archived from the original on November 4, 2011. Retrieved October 7, 2011.

- ↑ Box score: September 2, 2001—New York Yankees at Boston Red Sox Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved on May 14, 2009.

- ↑ "Umpire: 'I Just Cost That Kid a Perfect Game'". ESPN/Associated Press. June 2, 2010. Retrieved June 2, 2010.

- ↑ Kepner, Tyler (June 2, 2010). "Pitcher Loses Perfect Game on Questionable Call". New York Times. Retrieved June 2, 2010.

- ↑ "MLB.com At Bat". Major League Baseball. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ↑ Corcoran, Cliff (June 20, 2015). "Blame Umpires, Not Tabata for Scherzer's Lost Chance at Perfection". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ↑ Deveaux (2001), p. 49; Washington Post, "The Game in Detail", May 12, 1919, p. 4.

- ↑ New York Times, "Ruth Wallops Out His 28th Home Run", September 24, 1919, p. 23 (available online).

- ↑ See, e.g., Cook (2004), p. 236.

- ↑ Nowlin (2005), p. 69; Box score: September 18, 1971—Chicago Cubs at Philadelphia Phillies Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved on May 14, 2009.

- ↑ Burnett K's 14 over Six Innings Associated Press via ESPN.com. Retrieved on August 13, 2010; Box score: July 6, 2005—Milwaukee Brewers at Florida Marlins Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved on 2011-07-27.

- ↑ Arnold, Bill (July 14, 2006). "Beyond the Box Score—Almost Perfect". MLB.com. Retrieved May 11, 2009. Arnold does not list Bosio's 1993 game, as his list is restricted to games in which only the leadoff man reached base before the next 27 batters were retired.

- ↑ Elston (2006), pp. 173–174.

- ↑ Charlton's Baseball Chronology–1884 (May) Archived October 17, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Baseball Library. Retrieved on May 11, 2009. Note that this was an American Association game; the National League had not yet instituted the rule awarding hit batsmen first base. Charlton's Baseball Chronology, the source for this game, incorrectly describes Monte Ward retiring 27 straight batters after the first singled in a game of July 23, 1880. In fact, he also walked a batter and another reached on an error. See Boston Globe, "Providence 5, Cincinnati 0", July 24, 1880, p. 4.

- ↑ Boxscore—Game Played on Saturday, May 16, 1953 (D) at County Stadium Retrosheet. Retrieved on January 12, 2009.

- ↑ Boxscore—Game Played on Thursday, May 13, 1954 (N) at Connie Mack Stadium Retrosheet. Retrieved on January 12, 2009.

- ↑ Boxscore—Game Played on Friday, July 1, 1966 (N) at Shea Stadium Retrosheet. Retrieved on January 12, 2009.

- ↑ Boxscore—Game Played on Tuesday, May 19, 1981 (N) at Three Rivers Stadium Retrosheet. Retrieved on January 12, 2009.

- ↑ Boxscore—Game Played on Friday, June 11, 1982 (N) at Dodger Stadium Retrosheet. Retrieved on May 11, 2009.

- ↑ Boxscore—Game Played on Thursday, April 22, 1993 (N) at Kingdome Retrosheet. Retrieved on January 12, 2009.

- ↑ Boxscore—Game Played on Friday, July 7, 2006 (N) at Network Associates Coliseum Retrosheet. Retrieved on November 21, 2007.

- ↑ Boxscore—Game Played on Friday, May 10, 2013 at Busch Stadium ESPN. Retrieved on May 10, 2013.

- ↑ Schott and Peters (2003), p. 410.

- ↑ Fenster, Kenneth R. (May 1, 2006). "Nap Rucker (1884–1970)". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved June 1, 2009.

- ↑ Deveaux (2001), p. 53; Robbins (2004), pp. 238–239.

- ↑ Robbins (2004), p. 239. See also Deveaux (2001), pp. 170–171.

- ↑ Schneider (2005), p. 142; Robbins (2004), p. 240; Boxscore—Game Played on Friday, July 19, 1974 (N) at Cleveland Stadium. Retrosheet. Retrieved on April 22, 2009.

- ↑ McNeil (2003), p. 342; Robbins (2004), pp. 240–241; Boxscore—Game Played on Friday, June 27, 1980 (N) at Candlestick Park. Retrosheet. Retrieved on April 22, 2009.

- ↑ Westcott (2005), p. 77; Robbins (2004), pp. 241–242; Boxscore—Game Played on Wednesday, August 15, 1990 (N) at Veterans Stadium. Retrosheet. Retrieved on April 22, 2009.

- ↑ "Sanchez Makes Most of Opportunity, Throws No-hitter in Front of Father". ESPN.com/Associated Press. July 10, 2009. Retrieved July 11, 2009. Boxscore—Game Played on Friday, July 10, 2009 (N) at AT&T Park. Retrosheet. Retrieved on June 3, 2010.

- ↑ Greenberg, Neil (June 19, 2014). "Dodgers' Clayton Kershaw Throws the Best No-hitter of All Time". Washington Post. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ↑ Kepner, Tyler (October 3, 2015). "In Terms of One Outing, at Least, Max Scherzer Has Few Peers". New York Times. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ↑ Ladson, Bill; DiComo, Anthony (October 3, 2015). "No-no Encore: Scherzer Tosses 2nd of 2015". MLB.com. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ↑ Joseph, Andrew (August 23, 2017). "Rich Hill Lost a 9-inning No-hitter in the Most Heartbreaking Way Possible". USA Today. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ↑ "Los Angeles Dodgers at Pittsburgh Pirates Box Score, August 23, 2017". Baseball Reference. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

Sources

- Alvarez, Mark, ed. (1993). The Perfect Game: A Classic Collection of Facts, Figures, Stories and Characters from the Society for American Baseball Research (Taylor). ISBN 0-87833-815-2

- Anderson, David W. (2000). More Than Merkle: A History of the Best and Most Exciting Baseball Season in Human History (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press). ISBN 0-8032-1056-6

- Browning, Reed (2003). Cy Young: A Baseball Life (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press). ISBN 1-55849-398-0

- Buckley, Jr., James (2002). Perfect: The Inside Story of Baseball's Seventeen Perfect Games (Triumph Books). ISBN 1-57243-454-6

- Chen, Albert (2009). "The Greatest Game Ever Pitched", Sports Illustrated (June 1; available online).

- Coffey, Michael (2004). 27 Men Out: Baseball's Perfect Games (New York: Atria Books). ISBN 0-7434-4606-2

- Cook, William A. (2004). Waite Hoyt: A Biography of the Yankees' Schoolboy Wonder (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland). ISBN 0786419601

- Deutsch, Jordan A. et al. (1975). The Scrapbook History of Baseball (New York: Bobbs-Merrill). ISBN 0-672-52028-1

- Deveaux, Tom (2001). The Washington Senators, 1901–1971 (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland). ISBN 0-7864-0993-2

- Dewey, Donald, and Nicholas Acocella (1995). The Biographical History of Baseball (New York: Carroll & Graf). ISBN 1-57243-567-4

- Dickson, Paul (2009). The Dickson Baseball Dictionary, 3d ed. (New York: W. W. Norton). ISBN 0-393-06681-9

- Egan, James M. (2008). Base Ball on the Western Reserve: The Early Game in Cleveland and Northeast Ohio, Year by Year and Town by Town, 1865–1900 (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland). ISBN 0-7864-3067-2

- Elston, Gene (2006). A Stitch in Time: A Baseball Chronology, 3d ed. (Houston, Tex.: Halcyon Press). ISBN 1-931823-33-2

- Fleitz, David L. (2004). Ghosts in the Gallery at Cooperstown: Sixteen Little-Known Members of the Hall of Fame (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland). ISBN 0-7864-1749-8

- Forker, Dom, Robert Obojski, and Wayne Stewart (2004). The Big Book of Baseball Brainteasers (Sterling). ISBN 1-4027-1337-1

- Gallagher, Mark (2003). The Yankee Encyclopedia, 6th ed. (Champaign, Ill.: Sports Publishing LLC). ISBN 1-58261-683-3

- Hanlon, John (1968). "First Perfect Game In the Major Leagues", Sports Illustrated (August 26; available online).

- James, Bill. The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, rev. ed. (Simon and Schuster, 2003). ISBN 0-7432-2722-0

- Kennedy, Kostya (1996). "His Memory Is Perfect", Sports Illustrated (October 14; available online)

- Lewis, Allen (2002). "Tainted No-hitters", Baseball Digest (February; available online).

- Lupica, Mike (1999). Summer of '98: When Homers Flew, Records Fell, and Baseball Reclaimed America (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons). ISBN 0-399-14514-1

- McNeil, William F. (2003). The Dodgers Encyclopedia, 2d ed. (Champaign, Ill.: Sports Publishing LLC). ISBN 1-58261-633-7

- Nemec, David (2006 [1994]). The Official Rules of Baseball Illustrated (Guilford, Conn.: Globe Pequot). ISBN 1-59228-844-8

- Newman, Bruce (1981). "Perfect in Every Way", Sports Illustrated (May 25; available online).

- Nowlin, Bill (2005). "Rick Wise", in '75: The Red Sox Team That Saved Baseball, ed. Bill Nowlin and Cecilia Tan (Cambridge, Mass.: Rounder). ISBN 1-57940-127-9

- Okrent, Daniel, and Steve Wulf (1989). Baseball Anecdotes (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press). ISBN 0-19-504396-0

- Reisler, Jim (2007). The Best Game Ever: Pirates vs. Yankees, October 13, 1960 (New York: Carroll & Graf). ISBN 0-7867-1943-5

- Robbins, Mike (2004). Ninety Feet from Fame: Close Calls with Baseball Immortality (New York: Carroll & Graf). ISBN 0-7867-1335-6

- Schneider, Russell (2005). The Cleveland Indians Encyclopedia, 3d ed. (Champaign, Ill.: Sports Publishing LLC). ISBN 1-58261-840-2

- Schott, Tom, and Nick Peters (2003). The Giants Encyclopedia (Champaign, Ill.: Sports Publishing LLC). ISBN 1-58261-693-0

- Simon, Thomas P., ed. (2004). Deadball Stars of the National League (Brassey's). ISBN 1-57488-860-9

- Sullivan, Dean, ed. (2002). Late Innings: A Documentary History of Baseball, 1945–1972 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press). ISBN 0-8032-9285-6

- Thielman, Jim (2005). Cool of the Evening: The 1965 Minnesota Twins (Minneapolis, Minn.: Kirk House Publishers). ISBN 1886513716

- Vass, George (1998). "Here Are the 13 Most Fascinating No-Hitters", Baseball Digest (June).

- Vass, George (2002). "Seven Most Improbable No-Hitters", Baseball Digest (August; available online).

- Vass, George (2007). "One Out Away from Fame: The Final Out of Hitless Games Has Often Proved to Be a Pitcher's Toughest Conquest", Baseball Digest (June; available online).

- Westcott, Rich (2005). Veterans Stadium: Field of Memories (Philadelphia: Temple University Press). ISBN 1-59213-428-9

- Young, Mark C. (1997). The Guinness Book of Sports Records (Guinness Media). ISBN 0-9652383-1-8

- Zingg, Paul J., and Mark D. Medeiros (1994). Runs, Hits, and an Era: the Pacific Coast League, 1903–58 (Champaign: University of Illinois Press). ISBN 0-252-06402-X