League Park

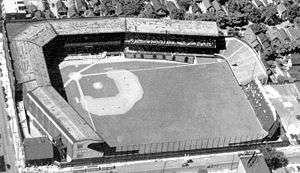

League Park from the air | |

| Former names | Dunn Field (1921–1927) |

|---|---|

| Location |

E 66th St. & Lexington Ave. Cleveland Ohio, United States |

| Coordinates | 41°30′41″N 81°38′39″W / 41.51139°N 81.64417°WCoordinates: 41°30′41″N 81°38′39″W / 41.51139°N 81.64417°W |

| Capacity |

9,000 (1891) 21,414 (1910) 22,500 (final) |

| Field size |

Left Field – 375 ft (114 m) Left-Center – 415 ft (127 m) Deep Center Field – 460 ft (140 m) Center Field – 420 ft (128 m) Right-Center – 340 ft (104 m) Right Field – 290 ft (88 m) |

| Surface | Grass |

| Construction | |

| Broke ground | 1891 |

| Opened | May 1, 1891 |

| Renovated | April 21, 1910 |

| Closed | September 21, 1946 |

| Demolished | 1951 |

| Architect | Osborn Engineering Company (1910) |

| Tenants | |

|

Cleveland Spiders (NL) (1891–1899) | |

|

League Park | |

| |

| Location | Lexington Ave. and E. 66th St., Cleveland, Ohio |

| Coordinates | 41°30′42″N 81°38′39″W / 41.51167°N 81.64417°W |

| Area | 1 acre |

| Built | 1908 |

| NRHP reference # | 79001808[1] |

| Added to NRHP | August 8, 1979 |

League Park was a baseball park located in Cleveland, Ohio, United States. It is situated at the northeast corner of E. 66th Street and Lexington Avenue in the Hough neighborhood. It was built in 1891 as a wood structure and rebuilt using concrete and steel in 1910. The park was home to a number of professional sports teams, most notably the Cleveland Indians of Major League Baseball. League Park was first home to the Cleveland Spiders of the National League from 1891 to 1899 and of the Cleveland Lake Shores of the Western League, the minor league predecessor to the Indians, in 1900. During 1914-1915, League Park also hosted the Toledo Mud Hens of the minor league American Association, under the name Cleveland Bearcats and then Spiders. In the late 1940s, the park was also the home field of the Cleveland Buckeyes of the Negro American League.

In addition to baseball, League Park was also used for American football, serving as the home field for several successive teams in the Ohio League and early National Football League (NFL) during the 1920s and 1930s, as well as for college football. Most notably, the Cleveland Rams of the NFL played at League Park in 1937 and for much of the early 1940s. Later in the 1940s, the Cleveland Browns used League Park as a practice field.

The Western Reserve Red Cats college football team from Western Reserve University played a majority of homes games at League Park from 1929 to 1941, and all home games after joining the Mid-American Conference from 1947 to 1949.[2] Western Reserve played many of its big-time college football games at League Park, including against the Ohio State Buckeyes,[3] Pittsburgh Panthers,[4] West Virginia Mountaineers,[5] and Cincinnati Bearcats.[2] Western Reserve and Case Tech often showcased their annual Thanksgiving Day rivalry game against one another,[6] as well as playing other Big Four Conference games against John Carroll and Baldwin-Wallace.

Although Cleveland Stadium opened in 1932 and had a much larger seating capacity and better access by car, League Park continued to be used by the Indians through the 1946 season, mainly for weekday games. Weekend games, games expecting a larger crowd, and night games were held at Cleveland Stadium. Most of the League Park structure was demolished in 1951, although some remnants still remain, including the original ticket office built in 1909.

After extensive renovation, the site was rededicated on August 23, 2014, as the Baseball Heritage Museum and Fannie Lewis Community Park at League Park.[7]

History

League Park was built for the Cleveland Spiders, who were founded in 1887 and played first in the American Association before joining the National League in 1889. Team owner Frank Robison chose the site for the new park, at the corner of Lexington Avenue and Dunham Street, later renamed East 66th Street, in Cleveland's Hough neighborhood, because it was along the streetcar line he owned. The park opened May 1, 1891, with 9,000 wooden seats, in a game against the Cincinnati Reds. The first pitch was made by Cy Young, and the Spiders won 12–3.[8] During their tenure, the Spiders finished as high as 2nd-place in the NL in 1892, 1895, and 1896, and won the Temple Cup, an early version of the modern National League Championship Series, in 1895. During the 1899 season, however, the Spiders had most of their best players stripped from the roster and sent to St. Louis by their owners, who had purchased the St. Louis Browns that year. Cleveland finished 20–134, drawing only 6,088 fans for the entire season, and were contracted by the National League. They were replaced the very next year by the Cleveland Lake Shores, then a minor league team in the American League. The American League declared itself a major league after the 1900 season and the Cleveland franchise, initially called the Blues, was a charter member for the 1901 season. The park was rebuilt for the 1910 season as a concrete-and-steel stadium, one of two to open that year in the American League, the other being Comiskey Park. The new park seated over 18,000 people, more than double the seating capacity of its predecessor. It opened April 21, 1910, with a 5–0 loss to the Detroit Tigers in front of 18,832 fans in a game also started by pitcher Cy Young.[9]

During 1914-1915, the Toledo Mud Hens of the minor league American Association were temporarily moved to League Park, to discourage the Federal League from trying to place a franchise in Cleveland. During their two-year stay, they were initially known as the Bearcats, then the Spiders, reviving the old National League club's name.

The Indians hosted games four through seven of the 1920 World Series at League Park. The series, won by the Indians five games to two, was notable as the first championship in franchise history, as well as for Game 5, which featured the first grand slam in World Series history and the first, and so far only, unassisted triple play in postseason history.[10]

In 1921, team owner "Sunny Jim" Dunn, who had purchased the team in 1916, renamed the park Dunn Field.[11][12] When Dunn died in 1922, his wife inherited the ballpark and the team. When Dunn's widow, by then known as Mrs. George Pross, sold the franchise in 1927 for $1 million to a group headed by Alva Bradley the name reverted to the more prosaic "League Park" (there were a number of professional teams' parks generically called "League Park" at the time).

From July 1932 through the 1933 season, the Indians played at the new and far larger Cleveland Stadium. However, the players and fans complained about the huge outfield, which reduced the number of home runs. Moreover, as the Great Depression worsened, attendance at the stadium plummeted.[11] After the 1933 season, the Indians exercised their escape clause in the lease at the stadium and returned to League Park for the 1934 season.[13]

The Indians played all home games at League Park for the 1934 and 1935 seasons, and played one home game at Cleveland Stadium in 1936 as part of the Great Lakes Exposition. In 1937, the Indians began splitting their schedule between the two parks, playing Sunday and holiday games at the stadium during the summer and the remainder at League Park, adding selected important games to the stadium schedule in 1938. Lights were never installed at League Park, and thus no major league night games were played there. However, at least one professional night game was played on July 27, 1931, between the Homestead Grays and the House of David, who borrowed the portable lighting system used by the Kansas City Monarchs.[13]

By 1940, the Indians played most of their home schedule at Cleveland Stadium, abandoning League Park entirely after the 1946 season. The final Indians game at League Park was played on Saturday, September 21, a 5–3 loss in 11 innings to the Detroit Tigers in front of 2,772 fans. League Park became the last stadium used in Major League Baseball never to install permanent lights.[14]

The Indians continued to own League Park until March 1950 when they sold it to the city of Cleveland for $150,000. After the demise of the Cleveland Buckeyes of the Negro American League during the 1950 season, League Park was no longer used as a regular sports venue. Most of the structure was demolished in 1951 by the city to convert the facility for use by local amateur teams and recreation and to prevent any competition with Cleveland Stadium. The lower deck seating between first base and third base remained, as did the Indians clubhouse under the third base stands. The Cleveland Browns began using League Park as a practice field in 1952, including the former clubhouse, until 1965. All of the remaining seating areas were removed in 1961 except for the area above the former clubhouse, which was finally torn down in 2002.[15]

Structure

When it originally opened in 1891, it had 9,000 wooden seats.[8] A single deck grandstand was behind homeplate, a covered pavilion was along the first base line, and bleachers were located at various other places in the park. The ballpark was shoehorned to fit into the Cleveland street grid, which contorted the dimensions into a rather odd rectangular shape by modern standards. The fence in left field was 385 feet (117 m), a tremendous 460 feet (140 m) away in center, and a short 290 feet (88 m) down the right field foul line.[16] However, batters had to hit the ball over a 40-foot (12 m) fence to get a home run (by comparison, the Green Monster at Fenway Park is 37 feet (11 m) high).[17]

It was essentially rebuilt prior to the 1910 season, with concrete and steel double-decker grandstands, expanding the seating capacity to 21,414. The design work was completed by Osborn Architects & Engineers, a local architecture firm that would go on to design several iconic ballparks over the next three years, including Comiskey Park, the Polo Grounds, Tiger Stadium, and Fenway Park. The front edge of the upper and lower decks were vertically aligned, bringing the up-front rows in the upper deck closer to the action, but those in back could not see much of foul territory.

The fence was rejiggered, bringing the left field fence in 10 feet closer (375 feet (114 m)) and center field fence in 40 feet (420 feet (130 m)); the right field fence remained at 290 feet (88 m).[16]

Batters still had to surmount a 40-foot (12 m) fence to hit a home run (by comparison, the Green Monster at Fenway Park is three feet shorter at 37 feet (11 m) high).[17] The fence in left field was only five feet tall, but batters had to hit the ball 375 feet (114 m) down the line to hit a home run, and it was fully 460 feet (140 m) to the scoreboard in the deepest part of center field. The diamond, situated in the northwest corner of the block, was slightly tilted counterclockwise, making right field not quite as easy a target as Baker Bowl's right field (which had a 60-foot (18 m) wall), for example.

Modern League Park

Today the site is a public park. A small section of the exterior brick facade (along the first-base side) still stands, as well as the old ticket office behind what was the right field corner. The last remnant of the grandstand, crumbling and presumably unsafe, was taken down in 2002 as part of a renovation process to the decaying playground.

On February 7, 2011, the Cleveland City Council approved a plan to restore the ticket house and remaining bleacher wall, as well as build a new diamond on the site of the old one (and with the same slightly counterclockwise tilt from the compass points).[18][19] On October 27, 2012, city leaders including Mayor Frank G. Jackson and Councilman TJ Dow took part in the groundbreaking of the League Park restoration. The project included a museum, a restoration of the ball field, and a community park featuring pavilions and walking trails.[20] The community park was dedicated in September 2013 as the Fannie M. Lewis Community Park at League Park.[21] Lewis was a city councilwoman who encouraged League Park's restoration.[21] Restoration was completed in 2014, and League Park reopened August 23 of that year.[7] As part of the renovation, the Baseball Heritage Museum (housing artifacts from baseball history as well as many specifically from the history of League Park) was relocated from downtown Cleveland to the restored ticket house.[7][22]

Notable events

Some historic events that took place at League Park include the following:

- May 1, 1891: The ballpark opened. Cy Young delivered the first pitch and the Spiders defeated the Cincinnati Reds 12–3.[23]

- October 17,18,19, 1892: The ballpark hosted the first three games of the first "split season" in the history of the National League. The opposing Boston Beaneaters eventually won the series over the Spiders.

- October 2,3,5, 1895: The ballpark hosted the first three games of that year's Temple Cup Series, a World Series precursor, the Spiders facing the Baltimore Orioles. Cleveland eventually clinched the series in Baltimore.

- October 8, 1896: The ballpark hosted the final game of that year's Temple Cup, a sweep by Baltimore, as well as Cleveland's final post-season appearance for the National League.

- November 26, 1896: The ballpark hosted its first college football game, seeing Case defeat Western Reserve 12-10.[24]

- August 30, 1899: Cleveland plays its final National League home game at League Park[25] in a season in which the team would win only 20 games while losing a record 134.

- 1900: The new American League, nominally a minor league, returns professional baseball to Cleveland after the National League contracted following the 1899 season.

- April 29, 1901: Cleveland's first home game in the American League after the league had declared itself a major league.[26]

- October 2, 1907: The debut of female pitching sensation Alta Weiss[27]

- October 2, 1908: Addie Joss' perfect game against the Chicago White Sox.[28]

- October 10, 1920: Game 5 of the 1920 World Series against the Brooklyn Dodgers,[29] includes several World Series "firsts":

- In the bottom of the first inning, Cleveland right fielder Elmer Smith hit the first grand slam home run in the history of the Series.

- In the bottom of the fourth inning, Cleveland pitcher Jim Bagby hit the first home run by a pitcher in a World Series game.

- In the top of the fifth inning, Cleveland second baseman Bill Wambsganss executed the first (and only, so far) unassisted triple play in Series history.

- October 12, 1920: The Cleveland Indians won their first World Series, winning game seven 3–0.[30]

- August 11, 1929: Babe Ruth hit his 500th career home run, the first player to achieve that milestone.[31]

- July 16, 1941: The final game of Joe DiMaggio's 56-game hitting streak. The streak was snapped the following night at Cleveland Stadium.[32]

- 1945: The Cleveland Buckeyes won the Negro Leagues World Series.

- December 2, 1945: The Cleveland Rams played their last game at League Park by topping the Boston Yanks, 20-7. Two weeks later, at Cleveland Stadium, they defeated the Washington Redskins, 15-14, to win the NFL Championship. A month later the franchise moved to Los Angeles.

- September 13, 1946: The Boston Red Sox clinched the American League pennant, the game's only score coming on a first-inning home run by Ted Williams.[33][34]

- September 21, 1946: The final game at League Park, a 5–3 loss to the Detroit Tigers. The Indians rounded out their 1946 home season with three games at Cleveland Stadium.[35]

- October 23. 1948: Kent State Golden Flashes and Western Reserve Red Cats played to a 14–14 tie in Ohio's first televised intercollegiate football game.[36]

References

- ↑ National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 http://www.case.edu/its/archives/Seasons/wfoot1947.htm

- ↑ http://www.case.edu/its/archives/Seasons/wfoot1934.htm

- ↑ http://www.case.edu/its/archives/Seasons/wfoot1948.htm

- ↑ http://www.case.edu/its/archives/Seasons/wfoot1938.htm

- ↑ http://blog.case.edu/archives/2010/11/15/case_vs_wru_thanksgiving_day_football_game

- 1 2 3 Warsinskey, Tim (August 23, 2014). "League Park reopens to a historic appreciation, beautiful restoration and hopeful future". The Plain Dealer. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- 1 2 Briggs, David (August 8, 2007). "League Park may glisten once again". MLB.com. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- ↑ Krsolovic, Ken; Fritz, Bryan (2013). League Park: historic home of Cleveland baseball, 1891–1946. McFarland & Company, Inc. pp. 8–12, 36–38. ISBN 978-0-7864-6826-3.

- ↑ Lewis, Franklin (2006) [1949]. The Cleveland Indians. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press [G.P. Putnam & Sons]. pp. 153–156. ISBN 978-0-87338-885-6.

- 1 2 "Clem's Baseball ~ League Park (IV)". Andrewclem.com. 1909-11-21. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- ↑ Krsolovic & Fritz, p. 71

- 1 2 Krsolovic & Fritz, pp. 99–104

- ↑ Krsolovic & Fritz, pp. 124–125

- ↑ Krsolovic & Fritz, pp. 157–177

- 1 2 League Park ballparksofbaseball.com (accessed July 22, 2010)

- 1 2 Krsolovic & Fritz, pp. 33–34

- ↑ Gillispie, Mark (2011-02-08). "Cleveland City Council approves spending to get historic League Park project started". Retrieved 2011-05-21.

- ↑ Briggs, David (2007-08-08). "League Park may glisten once again". Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- ↑ Scali, Maria. "Historic League Park to be Restored to Old Glory". WJW-TV. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- 1 2 Scali, Maria (2013-09-07). "Park Created to Honor Baseball's History". WJW-TV. Retrieved 2013-09-08.

- ↑ Martin, Angela. "Baseball Heritage Museum moves to fitting place — renovated League Park". MLB Pro Blog TribeVibe. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ↑ "1891 Log For League Park III in Cleveland, OH". Retrosheet.org. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- ↑ http://www.case.edu/its/archives/Seasons/cfoot1896.htm

- ↑ "Events of Wednesday, August 30, 1899". Retrosheet.org. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- ↑ "Events of Monday, April 29, 1901". Retrosheet.org. 1902-04-29. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- ↑ "Miss Alta Weiss of the Weiss All-Stars of Cleveland, Ohio". Retrieved 2009-09-26.

- ↑ "Addie Joss Perfect Game Box Score by Baseball Almanac". Baseball-almanac.com. 1908-10-02. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- ↑ "Retrosheet Boxscore: Cleveland Indians 8, Brooklyn Robins 1". Retrosheet.org. 1920-10-10. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- ↑ "Retrosheet Boxscore: Cleveland Indians 3, Brooklyn Robins 0". Retrosheet.org. 1920-10-12. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- ↑ "Retrosheet Boxscore: Cleveland Indians 6, New York Yankees 5". Retrosheet.org. 1929-08-11. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- ↑ "CNN/SI – The New York Yankees Greatest Hits". Sportsillustrated.cnn.com. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- ↑ "Retrosheet Boxscore: Boston Red Sox 1, Cleveland Indians 0". Retrosheet.org. 1946-09-13. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- ↑ "FDA approved US store. Cialis Sale – FDA APPROVED Drug Store". Baseballlibrary.com. Archived from the original on 2012-12-19. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- ↑ "Retrosheet Boxscore: Detroit Tigers 5, Cleveland Indians 3". Retrosheet.org. 1946-09-21. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- ↑ http://publish.netitor.com/photos/schools/mac/sports/m-footbl/auto_pdf/05_084-160_History.pdf

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to League Park. |

- League Park Information Site

- Diagram re-creation, and photo of the remnants of the ballpark

- Baseball Heritage Museum at League Park

| Events and tenants | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by National League Park |

Home of the Cleveland Spiders 1891–1899 |

Succeeded by last ballpark |

| Preceded by first ballpark |

Home of the Cleveland Indians 1901–1946 |

Succeeded by Cleveland Municipal Stadium |

| Preceded by first stadium Cleveland Municipal Stadium |

Home of the Cleveland Rams 1937 1942, 1944–1945 |

Succeeded by Shaw Stadium Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum |