Lindworm

Also known as a "snake" (ormr) or "dragon" (dreki), lindworms were popular motifs on runestones in 11th century Sweden. This runestone is identified as U 871. | |

| Grouping | Mythical creature |

|---|---|

| Other name(s) | White worm or whiteworm |

| Country | Various |

| Region | Northern Europe |

The Lindworm (cognate with Old Norse linnormr 'ensnaring snake', Norwegian linnorm 'dragon', Swedish lindorm, Danish lindorm 'serpent', German Lindwurm 'dragon') is either a dragon-like creature or serpent monster. In British heraldry, lindworm is a technical term for a wingless serpentine monster with two clawed arms in the upper body. In Norwegian heraldry a lindorm is the same as the wyvern in British heraldry.

A lindworm's appearance can vary from country to country and from tale to tale, but the most common depiction of lindworm is a wingless lindworm with a serpentine body, a dragon-like head, scaled or reptilian skin and two clawed arms in the upper body. The most common depiction of lindworms implies that such lindworms do not walk on their two limbs like a wyvern, but move like a mole lizard: they slither like a snake but they also use their arms to move themselves.

Etymology

In modern Scandinavian languages, the cognate lindorm can refer to any 'serpent' or monstrous snake, but in Norwegian heraldry, it is also a technical term for a 'sea serpent' (sjøorm), although it may also stand for a 'lindworm' in British heraldry.

In tales

In Norse mythology, the dwarf Fafnir from the Norse Völsunga saga is turned into a lindworm. In Grímnismál, Odin tells of several lindworms gnawing on Yggdrasil from below, "more than a unlearned fool would know". Odin names these lindworms (using the word "ormr" meaning snake and serpent) as Níðhöggr, Grábakr, Grafvölluðr (meaning he who digs deep beneath), Ofnir, Svafnir, Grafvitni (grave-wolf) and his sons Góinn and Móinn.[1][2] Grafvitni is used as a kenning for "serpent" in Krákumál.

The lindworm originates from Norse mythology and lindworms such as Fafnir. Later in the High Middle Ages, the lindworm myth spread throughout Europe, mostly north western Europe. Fafnir appears in the German Nibelungenlied as a lindwurm that lived near Worms.

Saxo Grammaticus begins his story of Ragnar Loðbrók, a semi-legendary king of Denmark and Sweden, by telling that a certain Þóra Borgarhjörtr receives a baby lindworm (lyngormr) as a gift from her father Herrauðr, the Earl of Götaland. As the lindworm grows, it eventually takes Þóra hostage, demanding to be supplied with no less than one ox a day, until she is freed by a young man in fur-trousers named Ragnar, who thus obtains the byname of Loðbrók ("hairy britches") and becomes Þóra's husband.

Some depictions of lindworms feature a lindworm with poisonous breath like Fafnir, while others don't.

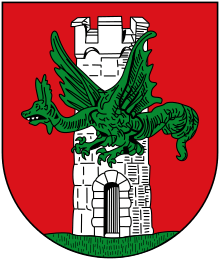

Another German tale from the 13th century tells of a lindworm that lived near Klagenfurt. Flooding threatened travelers along the river, and the presence of a dragon was blamed, when it was actually a lindworm. The story tells that a Duke offered a reward for anyone who could capture it; so some young men tied a bull to a chain, and when the lindworm swallowed the bull, it was hooked like a fish and killed.[3] The head of a 1590 lindworm statue in Klagenfurt is modeled on the skull of a woolly rhinoceros found in a nearby quarry in 1335. It has been cited as the earliest reconstruction of an extinct animal.[4][5]

The shed skin of a lindworm was believed to greatly increase a person's knowledge about nature and medicine.[6]

A serpentine monster with the head of a "salamander" features in the legend of the Lambton Worm, a serpent caught in the River Wear and dropped in a well, which after 3–4 years terrorized the countryside of Durham while the nobleman who caught it was at the Crusades. Upon return, he received spiked armour and instructions to kill the serpent, but thereafter to kill the next living thing he saw. His father arranged that after the lindworm was killed, a dog would be released and the son would kill that; but instead of releasing the dog the father ran to his son, and so incurred a malediction by the son's refusal of patricide. Bram Stoker used this legend in his short story Lair of the White Worm.

The sighting of a "whiteworm" once was thought to be an exceptional sign of good luck.[6]

The knucker or the Tatzelwurm is a wingless biped, and often identified as a lindworm. In legends, lindworms are often very large and eat cattle and bodies, sometimes invading churchyards and eating the dead from cemeteries.

In the 19th-century tale of "Prince Lindworm" (also "King Lindworm"), from Scandinavian folklore, a "half-man half-snake" lindworm is born, as one of twins, to a queen, who, in an effort to overcome her childless situation, has followed the advice of an old crone, who tells her to eat two onions. She did not peel the first onion, causing the first twin to be a lindworm. The second twin is perfect in every way. When he grows up and sets off to find a bride, the lindworm insists that a bride be found for him before his younger brother can marry. Because none of the chosen maidens are pleased by him, he eats each until a shepherd's daughter who spoke to the same crone is brought to marry him, wearing every dress she owns. The lindworm tells her to take off her dress, but she insists he shed a skin for each dress she removes. Eventually his human form is revealed beneath the last skin. Some versions of the story omit the lindworm's twin, and the gender of the soothsayer varies. A similar tale occurs in C.S. Lewis' novel The Voyage of the Dawn Treader.

Late belief in lindorm in Sweden

The belief in the reality of a lindorm, a giant limbless serpent, persisted well into the 19th century in some parts. The Swedish folklorist Gunnar Olof Hyltén-Cavallius collected in the mid 19th century stories of legendary creatures in Sweden. He met several people in Småland, Sweden that said they had encountered giant snakes, sometimes equipped with a long mane. He gathered around 50 eyewitness reports, and in 1884 he set up a big reward for a captured specimen, dead or alive.[7] Hyltén-Cavallius was ridiculed by Swedish scholars, and since nobody ever managed to claim the reward it resulted in a cryptozoological defeat. Rumours about lindworms as actual animals in Småland rapidly died out.[8][9]

See also

References

- ↑ "76 (Salmonsens konversationsleksikon / Anden Udgave / Bind X: Gradischa—Hasselgren)". runeberg.org.

- ↑ "Sången om Grimner (Eddan, De nordiska guda- och hjältesångerna)". runeberg.org. 22 January 2018.

- ↑ J. Rappold, Sagen aus Kärnten (1887).

- ↑ Mayor, Adrienne (2000). The first fossil hunters: paleontology in Greek and Roman times. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-08977-9.

- ↑ Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London. Academic Press. 147-148. 1887.

- 1 2 "645-646 (Nordisk familjebok / Uggleupplagan. 16. Lee - Luvua)". runeberg.org. 22 January 2018.

- ↑ G. O. Hyltén-Cavallius, Om draken eller lindormen, mémoire till k. Vetenskaps-akademien, 1884.

- ↑ Meurger, Michel (1996). "The Lindorms of Småland". Arv - Nordic Yearbook of Folklore. 52: 87–9.

- ↑ 1925-, Sjögren, Bengt, (1980). Berömda vidunder. [Laholm]: Settern. ISBN 9175860236. OCLC 35325410.

External links

- King Lindorm, translated from: Grundtvig, Sven, Gamle danske Minder i Folkemunde (Copenhagen, 1854—1861).

- Gesta Danorum, Book 9 by Saxo Grammaticus.

- A retelling of Ragnar Lodbrok's story from Teutonic Myth and Legend by Donald Mackenzie.

- Saint George Legends from Germany and Poland

- Lindorm, an article from Nordisk Familjebok (1904–1926), a Swedish encyclopedia now in the Public Domain.

- Lindormen, a ballad in Swedish published at the Mutopia project.