Law of Jante

The Law of Jante (Danish: Janteloven)[note 1] is a code of conduct said to be common in Nordic countries, that portrays doing things out of the ordinary, being overtly personally ambitious, or not conforming, as unworthy and inappropriate.

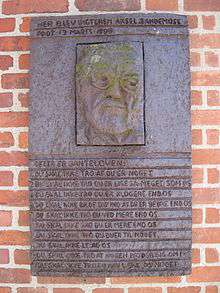

The attitudes were first formulated in the form of the ten rules of Jante Law by the Dano-Norwegian author Aksel Sandemose, in his satirical novel A Fugitive Crosses His Tracks (En flyktning krysser sitt spor, 1933), but the actual attitudes themselves would be older.[1] His novel portrays the fictional small Danish town Jante, which he modelled upon his native town Nykøbing Mors in the 1930s, which was typical of all small towns and communities, where nobody was anonymous.[2]

Used generally in colloquial speech in the Nordic countries as a sociological term to denote a condescending attitude towards individuality and success, the term refers to a mentality that diminishes individual effort and places all emphasis on the collective, while simultaneously denigrating those who try to stand out as individual achievers.[3]

Definition

There are ten rules in the law as defined by Sandemose, all expressive of variations on a single theme and usually referred to as a homogeneous unit: You are not to think you're anyone special or that you're better than us.

The ten rules state:

- You're not to think you are anything special.

- You're not to think you are as good as we are.

- You're not to think you are smarter than we are.

- You're not to imagine yourself better than we are.

- You're not to think you know more than we do.

- You're not to think you are more important than we are.

- You're not to think you are good at anything.

- You're not to laugh at us.

- You're not to think anyone cares about you.

- You're not to think you can teach us anything.

In the book, the Janters who transgress this unwritten 'law' are regarded with suspicion and some hostility, as it goes against the town's communal desire to preserve harmony, social stability and uniformity.

An eleventh rule recognised in the novel as 'the penal code of Jante' is:

- Perhaps you don't think we know a few things about you?

From the chapter Maybe you don't think I know something about you:

"That one sentence (the eleventh rule), which acts as the penal code of Jante, as such was rich in content. It was a charge of all sorts of things, and that it also had to be, because absolutely nothing was allowed. It was also an elaborate indictment, with all kinds of unspecified penalties given to be expected. Furthermore it was useful, depending fully on tone of voice, in financial extortion and enticement into criminal acts, and it could also be the best means of defense."

Sandemose wrote about the working class in the town of Jante, a group of people of the same social position. He expressly stated in later books that the social norms of Jante were universal and not intended to depict any particular town or country. Sandemose did not invent the rules; he was seeking to formulate and describe attitudes that had already been part of the Danish and Norwegian psyche for centuries.

Sociological effects

Although intended as criticism, the meaning of the Law of Jante has shifted to refer to personal criticism of people who want to break out of their social groups and reach a higher position in society in general.[4]

It is common in Scandinavia to claim the Law of Jante as something quintessentially Danish, Norwegian or Swedish. The rules are treated as a way of behaving in order to fit in and results in dressing similarly and the types of cars that people buy and buying similar products for their homes.[5]

It's commonly stated that Jante Law is for people in the provinces, but commentators have suggested that metropolitan areas are also affected.[5]

While the original intention was as satire, Kim Orlin Kantardjiev, a Norwegian politician[6] and educational advisor, claims that the Law of Jante is taught in schools, is treated more as a social code to encourage group behaviour, and has been credited with making Nordic countries more harmonious and equal by pointing out the intrinsic conflicts between individuality and social conformity. He also asserts that the laws may be one of the reasons Nordic countries have high happiness scores.[5] and feels the law might be summarised as "You shouldn't think you're better than everyone else."[5]:4:59 Though the law, as defined by Sandemose, is meant to control and shame achievers of all kinds, regardless of wealth, Kantardjiev makes the association that in countries such as America, being rich allows people to behave differently, and Jante Laws tend to level out society, as the people as a whole get to set the rules, not the rich alone.[5]

In Scandinavia, articles appear regularly, however, which link the Law of Jante to high suicide rates.[7]

Backlash has occurred against the rules, and in Norway someone even placed a grave for Jante Laws, declaring them dead in 2005. However, others have questioned whether they will ever go away, as they may be firmly entrenched in society.[5]

See also

References

- ↑ Scott, Mark (18 December 2003). "Signs of Cracks in the Law of Jante". The New York Times. Retrieved 2013-12-22.

Taken from a book by the Danish author Aksel Sandemose, the concept suggests that the culture within Scandinavian countries discourages people from promoting their own achievements over those of others.

- ↑ Translator note, En flygtning krydser sit spor, 2nd ed.

- ↑ Adleswärd, Viveka (2 November 2003). "Avundsjukan har urgamla anor" [Jealousy has ancient ancestry]. Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ↑ Andersen, Steen (6 July 1992). "Den løbske Jantelov" [The Runaway Jante Law]. Morsø Folkeblad. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 BBC Ideas Forget hygge: The laws that really rule in Scandinavia

- ↑ Agenda Magasin online

- ↑ Klas Leffler in MittMedia Allehanda Västernorrland 2016-07-16

Notes

Further reading

- Sandemose, Aksel (1933). En flyktning krysser sitt spor. Oslo: Aschehoug (Repr. 2005). ISBN 82-03-18914-8

- Sandemose, Aksel (1936). A fugitive crosses his tracks. translated by Eugene Gay-Tifft. New York: A.A. Knopf.

- Koldau, Linda Maria (2013): Jante Universitet. (Jante University). Vol. 1: Den skønne facade (The Beautiful Facade); Vol. 2: Uddannelseskatastrofen (Educational Disaster); Vol. 3: Totalitære strukturer (Totalitarian Structures). Hamburg: Tredition. ISBN 978-3-8495-0351-2 (Vol. 1); ISBN 978-3-8495-0350-5 (Vol. 2); ISBN 978-3-8495-0266-9 (Vol. 3). In Danish language.

- Koldau, Linda Maria (2013): Educational Disaster. The Destruction of Our Universities: The Danish Case. (abridged English version of Jante Universitet containing the most important analyses and a chapter on Jante Law mentality in Danish education). Hamburg: Tredition (forthcoming). ISBN 978-3-8495-4936-7. In English language.

- Steffen, Juliane (2011): "Hjem til Jante" (Home to Jante), concise analysis of the mechanisms of Jante Law at Danish universities, published in: Linda Maria Koldau: Jante Universitet. Vol. 2: Uddannelseskatastrofen. Hamburg: Tredition, 2013, pp. 464–466. ISBN 978-3-8495-0350-5 (Vol. 2). In Danish language.

Andersen, Steen: Nye forbindelser. Pejlinger i Aksel Sandemoses forfatterskab. Vordingborg: Attika, 2015. ISBN 978-87-7528-8700. In Danish Language.