Kalenjin prehistory

Kalenjin prehistory refers to the history of the linguistic ancestors of the Kalenjin people before the adoption of writing, this being from the time they separated from the Highland Nilotes (estimated to correspond to the late 1st millennium AD) and before, until the mid-19th century. The Kalenjin like a number of African and other world cultures had an oral tradition. The efficacy of the tradition is highlighted by confirmation of narratives spanning thousands of years using contemporary studies such as linguistics and archaeology, although the details in the narratives have often been distilled to the bare essential. The terms "ancient history", "early history", and "pre-colonial history" are also used by different sources to describe this same period of Kalenjin history.

Origins

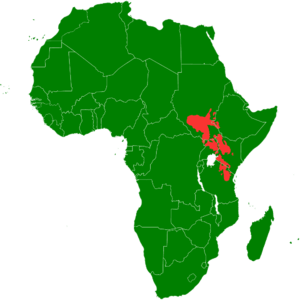

Linguistic evidence points to the eastern Middle Nile Basin south of the Abbai River as the ancient homelands of the Kalenjin. That is to say south-east of present-day Khartoum. They were not a distinct group of people at this time but part of a wider society today referred to as Nilotic peoples.[1]

Beginning in the second millennium B.C., particular Nilotic communities began to move southward into present day South Sudan where most settled. However the societies today referred to as the Southern Nilotes pushed further on, reaching what is present day north-eastern Uganda by 1000 B.C.[1] The most northern area that is recognized as inhabited by these early Kalenjin lies in the present day Jie and Dodoth country in Uganda.[2]

Early presence in Kenya

Eastern Cushitic Interaction

Ehret postulates that between 1000 and 700 BC, the Southern Nilotic speaking communities, who kept domestic stock and possibly cultivated sorghum and finger millet,[3] lived next to an Eastern Cushitic speaking community with whom they had significant cultural interaction. The general location of this point of cultural exchange being somewhere near the common border between Sudan, Uganda, Kenya and Ethiopia.

This corresponds with a number of historical narratives from the various Kalenjin sub-tribes which point to Tulwetab/Tuluop Kony (Mount Elgon) as their original point of settlement in Kenya. However, there are also accounts from Kalenjin speaking communities, in particular the Sebeii/Sabaot, living near Mt Elgon who point to Kong'asis (the East) and more specifically the Cherangani Hills as their original homelands in Kenya.[4]

The impact of the cultural exchange that occurred in near the Mt Elgon region was most notable in borrowed loan words, adoption of the practice of circumcision and the cyclical system of age-set organisation.[5]

Bantu Interaction

Linguistic studies indicate separate and significant interaction between the Southern Nilotic speakers and Bantu speaking communities. Word evidence shows that in this interaction, there was highly gendered migration from the Bantu speaking communities into Southern Nilotic-speaking areas during the period, ca. 500-800 A.D., with Luhya women being the migrants.

The evidence for this lies in the words that passed from the Bantu language into the Southern Nilotic language during this period. In contrast to the wide variety of Kalenjin loanwords in Luhya today, all but one of the words that were adopted from Luhya relate to cultivation and cooking, which were traditionally women's duties in ancient Luhya society.

It has been suggested that the social institution of marriage led to the select migration. In that, whereas the Southern Nilotic speaking pastoralists contracted marriage through payment of cattle and other livestock by the groom's family to the prospective bride's family, the Bantu of 1500 to 2000 years ago likely contracted marriage through bride service, whereby the prospective groom would work in the potential bride's household for a period of time. This arrangement therefore served to make men the migrants in contrast to payment of bride price which made women the migrants.

The marrying of Luhya women to Kalenjin men would have conferred benefits to men of both societies at the time since for the Kalenjin, Luhya women would have contributed expanded agricultural variety and productivity to the homestead. On the other hand, a Luhya father, by marrying his daughter to a Kalenjin man could increase his own wealth and position within Luhya society. Over the long term such relations, by increasing men's wealth in cattle, undoubtedly helped bring into being new customary balance's between men and women's authority and status in Luhya society. These societies are today patrilineal unlike the ancient Luhya societies which appear to have been matrilineal.[6]

Sirikwa era

From the archaeological record, it is postulated that the emergence and early development of the Sirikwa culture occurred in the central Rift Valley i.e. Rongai/Hyrax Hill, not later than the 12th century A.D. From here the culture expanded into the western highlands, the Mt. Elgon region and possibly into Uganda.[7]

For several centuries, the Sirikwa, linguistic ancestors of the Kalenjin would be the dominant population of the western highlands of Kenya. At their greatest extent, their territories covered the highlands from the Chepalungu and Mau forests northwards as far as the Cherangany Hills and Mount Elgon. There was also a south-eastern projection, at least in the early period, into the elevated Rift grasslands of Nakuru which was taken over permanently by the Maasai, probably no later than the seventeenth century. Here Kalenjin place names seem to have been superseded in the main by Maasai names[8] notably Mount Suswa (Kalenjin - place of grass) which was in the process of acquiring its Maasai name, Ol-doinyo Nanyokie, the red mountain during the period of European exploration.[9]

Archaeological evidence indicates a highly sedentary way of life and a cultural commitment to a closed defensive system for both the community and their livestock during the Sirikwa era of Kalenjin prehistory. Family homesteads featured small individual family stock pens, elaborate gate-works and sentry points and houses facing into the homestead; defensive methods primarily designed to proof against individual thieves or small groups of rustlers hoping to succeed by stealth.[10] A commitment to trade in this period is also highlighted by fact that the ancient caravan routes from the Swahili coast led to the territories of the Kalenjin ancestors.[11]

The Maasai era

The innovation of heavier and deadlier spears amongst the neighboring Maasai led to significant changes in methods and scale of raiding bringing about the Maasai era. The change in methods introduced by the Maasai however consisted of more than simply their possession of heavier, and more deadly spears. There were more fundamental differences of strategy, in fighting and defense and also in organization of settlements and of political life.[10] As cattle raiding increased - or as the methods and scale of raiding were transformed during the early part of the Maasai era - the traditional defensive methods, and the settlement system and social organization which were integrated with them, proved vulnerable. 'One might be tempted to imagine the Sirikwa, as they felt competition, cattle theft and military threats more keenly, redoubling their defensive efforts and developing an increasingly inward world-view'. The old settlement system, the archaeological 'Sirikwa holes' proved inadequate against larger, longer-distance raiding parties which, in rounding up cattle did not hesitate to smash or burn down fences. Therefore, far from being effective devices for livestock protection, they became veritable traps. They and the Sirikwa way of living had to be discontinued.[3]

In the Maasai era, guarding cattle on the plateaus depended less on elaborate defenses and more on mobility and cooperation, both of these being combined with grazing and herd-management strategies. The practice of the later Kalenjin - that is, after they had abandoned the Sirikwa pattern and had ceased in effect to be Sirikwa - illustrates this change vividly. On their reduced pastures, notably on the borders of the Uasin Gishu plateau, they would when bodies of raiders approached relay the alarm from ridge to ridge, so that the herds could be combined and rushed to the cover of the forests. There, the approaches to the glades would be defended by concealed archers, and the advantage would be turned against the spears of the plains warriors.[3]

By the close of the 18th century, the Sirikwa, an era that represented both a period and people with a distinctive way of living, had been abandoned and the Kalenjin period had begun. Some Sirikwa, especially in the south-east around Nakuru, were Maasai-ized, their cultural and ecological experience proving instrumental to Maasai pastoralism as it established itself in the fine high grasslands and then radiated southwards. Certain Sirikwa elements moved further afield, southwards, some appear to have been assimilated into Maasai sections in the Loita-Mara region and others in Tatog. Equally large, or larger numbers helped to form the Kuria and related peoples between the Mara and Lake Victoria where they adopted a Bantu language but retained the form and nomenclature of certain Sirikwa-Kalenjin social institutions. Northward again, more has been recorded about likely Sirikwa elements, now essentially assimilated into the Pokot, Karimojong and other peoples. Sometimes, they are linked to 'Oropom' memories in the region. the names 'Siger' and 'Sangwir', are usedboth of places and people considered semantically if not etymologically cognate with Sirikwa. For the most part however, the main body of the Sirikwa remained where they had always been and re-accultured to form the new Kalenjin communities all around the Uasin Gishu plateau and further south.[12]

More than any of the other sections, the Nandi and Kipsigis, in response to Maasai expansion, borrowed from the Maasai some of the traits that would distinguish them from other Kalenjin: large-scale economic dependence on herding, military organization and aggressive cattle raiding, as well as centralized religious-political leadership. The family that established the office of orkoiyot (warlord/diviner) among both the Nandi and Kipsigis were nineteenth-century Maasai immigrants. By 1800, both the Nandi and Kipsigis were expanding at the expense of the Maasai. This process was halted in 1905 by the imposition of British colonial rule.[13]

Resistance to British rule

In the later decades of the 19th century, at the time when the early European explorers started advancing into the interior of Kenya, Nandi territory was a closed country. Thompson in 1883 was warned to avoid the country of the Nandi, who were known for attacks on strangers and caravans that would attempt to scale the great massif of the Mau.[14]

Matson, in his account of the resistance, shows 'how the irresponsible actions of two British traders, Dick and West, quickly upset the precarious modus vivendi between the Nandi and incoming British'.[15] This would cause more than a decade of conflict led on the Nandi side by Koitalel Arap Samoei, the Nandi Orkoiyot at the time.

Until the mid-20th century, the Kalenjin did not have a common name known to the external world and were usually referred to as the 'Nandi-speaking tribes' by scholars and colonial administration officials.[16]

References

- 1 2 Ehret, Christopher. An African Classical Age: Eastern & Southern Africa in World History 1000 B.C. to A.D.400. University of Virginia, 1998, p.7

- ↑ De Vries, Kim. Identity Strategies of the Argo-pastoral Pokot: Analyzing ethnicity and clanship within a spatial framework. Universiteit Van Amsterdam, 20007 p. 39

- 1 2 3 Spear, T. and Waller, R. Being Maasai: Ethnicity & Identity in East Africa. James Currey Publishers, 1993, p. 47 (online)

- ↑ Kipkorir, B.E. The Marakwet of Kenya: A preliminary study. East Africa Educational Publishers Ltd, 1973, pg. 64

- ↑ Ehret, Christopher. An African Classical Age: Eastern & Southern Africa in World History 1000 B.C. to A.D.400. University of Virginia, 1998, p.161-164

- ↑ Lacassen, J. Lacassen, L. and Manning, P, Migration History in World History: Multidisciplinary Approaches, 2010 pg. 139

- ↑ Kyule, David M., 1989, Economy and subsistence of iron age Sirikwa Culture at Hyrax Hill, Nakuru: a zooarcheaological approach p.211

- ↑ Spear, T. and Waller, R. Being Maasai: Ethnicity & Identity in East Africa. James Currey Publishers, 1993, p. 42 (online)

- ↑ Pavitt, N. Kenya: The First Explorers, Aurum Press, 1989, p. 107

- 1 2 Spear, T. and Waller, R. Being Maasai: Ethnicity & Identity in East Africa. James Currey Publishers, 1993, p. 44-46 (online)

- ↑ Hollis A.C, The Nandi - Their Language and Folklore. The Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1909, p. xvii

- ↑ Spear, T. and Waller, R. Being Maasai: Ethnicity & Identity in East Africa. James Currey Publishers, 1993, p. 47-48 (online)

- ↑ Nandi and Other Kalenjin Peoples - History and Cultural Relations, Countries and Their Cultures. Everyculture.com forum. Accessed 19 August 2014

- ↑ Pavitt, N. Kenya: The First Explorers, Aurum Press, 1989, p. 121

- ↑ Nandi Resistance to British Rule 1890–1906. By A. T. Matson. Nairobi: East African Publishing House, 1972. Pp. vii+391

- ↑ cf. Evans-Pritchard 1965.