K-19: The Widowmaker

| K-19: The Widowmaker | |

|---|---|

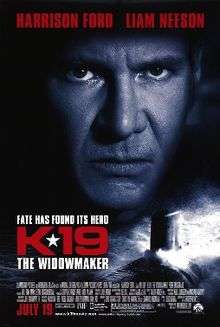

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Kathryn Bigelow |

| Produced by |

|

| Screenplay by | Christopher Kyle |

| Story by | Louis Nowra |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Klaus Badelt |

| Cinematography | Jeff Cronenweth |

| Edited by | Walter Murch |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | |

Release date |

|

Running time | 138 minutes[1] |

| Country |

|

| Language |

English Russian |

| Budget | $90 million[2] |

| Box office | $65.7 million[3] |

K-19: The Widowmaker is a 2002 historical thriller film about the first of many disasters that befell the Soviet submarine K-19.

K-19: The Widowmaker was directed by Kathryn Bigelow, and stars Harrison Ford and Liam Neeson. The screenplay was adapted by Christopher Kyle, with the story written by Louis Nowra, based on real life events depicted in a book by Peter Huchthausen. The film is an international co-production between the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, and Canada.

Plot

In 1961, the Soviet Union launches its first ballistic missile nuclear submarine, the K-19, commanded by Captain Alexei Vostrikov (Harrison Ford), aided by executive officer Mikhail Polenin (Liam Neeson). Polenin was the crew's original captain, and they have served together for some time; Vostrikov's appointment is alleged to have been aided by his wife's political connections, as well as Polenin's tendency to put the crew's morale and safety before the pride of the Soviet Union. During his first inspection, Vostrikov discovers the reactor officer to be drunk and asleep on duty and sacks him, ordering Polenin to request a replacement.

The replacement reactor officer, Vadim Radtchenko (Peter Sarsgaard), is fresh from the naval academy's nuclear program. Before the launch, the medical officer is killed when struck by an oncoming truck, and is replaced by command's foremost medical officer, who hails from the army and has never been out to sea. During the official launch of the K-19, the bottle of champagne fails to break when it strikes the bow, considered to be a sign of ill fortune (according to some naval traditions, a young woman is supposed to break a bottle of alcoholic/celebratory beverage against a ship's hull at its christening/maiden launch; if the bottle did not break, it was taken to be an ill omen).

With Captain Vostrikov's constant drilling, the crew's performance improves. The first mission of the K-19 is to surface in the Arctic to fire an unarmed intercontinental ballistic missile as a test, then to patrol a zone in the Atlantic within striking range of New York City and Washington D.C. as a Soviet deterrent to American ambitions. To test the submarine's limits, Vostrikov orders the K-19 to submerge past its maximum operational depth of 250 meters to a depth closer to its "crush depth" (300 meters), then surface rapidly at full-speed to break through the Arctic pack-ice, estimated at no more than one meter thick. Polenin regards this maneuver as dangerous and storms off the bridge. Scraping along the underside of the ice, the K-19 breaks through with little difficulty. The test missile is launched successfully.

En route to the patrolling area, a pipe for the reactor cooling system springs a leak and then bursts completely. Control rods are inserted to stop the reactor, but without coolant the reactor temperature continues to rise rapidly. During an officers' review of emergency protocols, it is revealed that back-up coolant systems were not installed; without these, the protocols are useless (they are based on the assumption that back-up systems are in place). The K-19 surfaces to contact fleet command about the accident and await orders. The cable for the long-range transmitter antenna on the conning tower, however, is damaged, possibly due to the earlier surfacing maneuver in the Arctic.

An engineering team conceives a plan to rig a makeshift coolant system; because Polenin has discovered that the submarine was supplied with chemical, not nuclear, suits, teams are instructed to work in 10-minute shifts to limit radiation exposure. The first group emerges vomiting and heavily blistered; the second and third teams succeed in cooling the reactor, but all are severely ill with radiation poisoning. As radiation levels slowly rise inside the ship, the submarine surfaces and most of the crewmen are ordered topside. Radtchenko, the reactor officer, is initially assigned to go as part of the third team to finish the operation, but his fear upon witnessing the first team's radiation injuries overtakes him, and the crew chief joins the third team in his place.

A United States Navy helicopter from a nearby destroyer approaches the K-19; the destroyer and asks if the K-19 requires assistance. Vostrikov tells the destroyer "no" and refuses to allow the Americans anywhere near K-19. Back in the Soviet Union, the government worries about the condition of the K-19 because it has ceased contact with fleet command (due to its disabled long-range communicator) but has been spotted by Soviet spy aircraft in the vicinity of the American destroyer.

With the hope that fleet command will send some diesel submarines to tow the K-19 back to port, Vostrikov ceases the mission and orders a heading that would return to port, but at a pace that could kill the entire crew with radiation sickness if rescue is not forthcoming. Shortly thereafter, the repair crews' pipework springs leaks and the reactor temperature begins to rise once again. This incites unrest among some of the crew, and in an accident, fuel that had been previously removed from a torpedo ignites, causing a fire in that compartment. Initially ordering the emergency fire suppression system to be activated (which would deprive the fire of oxygen, but suffocate anyone inside that area), Vostrikov is talked down by Polenin, who personally goes to assist the fire crew in putting out the fire. This leaves Vostrikov facing some hostile crew and officers who no longer have Polenin present to moderate them, and two officers enact a pre-planned mutiny to remove Vostrikov from command. Radtchenko, who earlier panicked and backed out from joining the repair crews, this time enters the reactor area alone and commences a second repair attempt.

Polenin returns to the command deck after helping put out the torpedo room fire; upon seeing Vostrikov handcuffed to a ladder, he deceives the mutineers into handing over their weapons, places them under arrest, and then frees Vostrikov. Believing the repairs to have failed and unaware that Radtchenko had gone in alone to patch up the new leaks, Vostrikov, at the behest of Polenin, tells the crew what has happened, and his rationale for a subsequent dive to attempt another repair; he is afraid that if the reactor were to overheat, it could set off the actual nuclear warheads carried by the K-19 and the accident would destroy not just the K-19 but also the nearby American ship, provoking an American retaliatory attack and possibly inciting nuclear war. Vostrikov then waits for the crew to respond to his recommendation; the crew subsequently responds in the affirmative, and the K-19 dives. Vostrikov then goes back to the reactor section after hailing Radtchenko and receiving no reply. Radtchenko's repairs were successful, but he received a heavier dose of radiation than earlier teams, having stayed in 18 minutes to complete his repair. Unable to see and too weak to properly extricate himself from the reactor chamber, Radtchenko is dragged out personally by Captain Vostrikov. The repairs prevent a reactor meltdown, but radiation is leaking throughout the submarine due to irradiated steam leakage from the reactor's damage.

A Soviet diesel submarine finally reaches the K-19; it relays orders from fleet command to confine the crew on the submarine until a freighter can pick them up. Knowing it would be too dangerous to stay, Vostrikov orders the crew to be evacuated to the diesel submarine, despite knowing he will most likely lose his command and be sent to a gulag for countermanding a direct order. The crew is evacuated and returns to the Soviet Union, without having to receive assistance from the nearby Americans. After the incident, Captain Vostrikov is tried for endangering the mission and disobeying a direct order, but Polenin and the other officers and crew of the K-19 come to his defense.

Epilogue

Epilogue lead-in text indicates that charges against Captain Vostrikov were dropped, but that the former crew of the K-19 is ordered to maintain silence regarding the incident, and Vostrikov is never given command of a submarine again. All seven men who went into the reactor chamber to effect repairs died of radiation poisoning days after returning home, and twenty other crew members later died from radiation sickness acquired during the incident. It is not until the fall of Communism nearly three decades later that the members of the K-19 crew could openly discuss what happened.

Later in 1989, an aged Captain Vostrikov meets Polenin on the anniversary of the day they were rescued. The commanders enter a cemetery where K-19 survivors have met since the incident. Vostrikov is visibly moved as he greets the men and informs them that he nominated the crewmen who died from radiation poisoning — 28 in total — for the Hero of the Soviet Union award, but was told the honor was reserved for combat veterans. Remarking that "what good are honors from such people," referring to the committee that turned down his recommendation, Vostrikov toasts the survivors and the deceased crew who sacrificed their lives to honor their duty to their crewmates.

Cast

- Harrison Ford as Captain 2nd Rank Alexei Vostrikov, Commanding Officer

- Liam Neeson as Captain 3rd Rank Mikhail "Misha" Polenin, Executive Officer

- Peter Sarsgaard as Lieutenant Vadim Radtchenko, Reactor Officer

- Joss Ackland as Marshal Zolentsov, Defense Minister

- John Shrapnel as Admiral Bratyeev

- Donald Sumpter as Captain 3rd Rank Gennadi Savran, Medical Officer

- Tim Woodward as Vice-Admiral Konstantin Partonov

- Steve Nicolson as Captain 3rd Rank Yuri Demichev, Torpedo Officer

- Ravil Isyanov as Captain 3rd Rank Igor Suslov, Political Officer

- Christian Camargo as Petty Officer Pavel Loktev, Senior Reactor Technician

- George Anton as Captain-Lieutenant Konstantin Poliansky, Missile Officer

- James Francis Ginty as Seaman Anatoly Subachev, Reactor Technician

- Lex Shrapnel as Captain-Lieutenant Mikhail Kornilov, Communications Officer

- Ingvar Eggert Sigurðsson as Captain 3rd Rank Viktor Gorelov, Chief Engineer

- Sam Spruell as Senior Seaman Dmitri Nevsky

- Sam Redford as Petty Officer 2nd Class Vasily Mishin

- Peter Stebbings as Kuryshev

- Shaun Benson as Chief Petty Officer Leonid Pashinski

- Kristen Holden-Ried as Captain-Lieutenant Anton Malahov

- Dmitry Chepovetsky as Sergei Maximov

- Tygh Runyan as Petty Officer 1st Class Maxim Portenko, Sonar Operator

- Jacob Pitts as Grigori

- Michael Gladis as Senior Seaman Yevgeny Borzenkov

- JJ Feild as Andrei Pritoola

- Peter Oldring as Vanya Belov

- Joshua Close as Viktor

- Jeremy Akerman as Fyodor Tsetkov, Captain of the S-270

Production

"The Widowmaker" nickname was used only in the film. In real life, the submarine had no nickname until the nuclear accident on July 3, 1961, when she got her actual nickname "Hiroshima".[4]

K-19: The Widowmaker cost $100 million to produce,[5][6] but gross returns were only $35 million in the United States and $30.5 million internationally.[3] The film was not financed by a major studio (National Geographic was owned by National Geographic Partners, a joint venture with 21st Century Fox and The National Geographic Society), making it one of the most expensive independent films to-date. K-19: The Widowmaker was filmed in Canada, specifically Toronto, Ontario; Gimli, Manitoba; and Halifax, Nova Scotia.

The producers made some efforts to work with the original crew of K-19, who took exception to the first version of the script available to them.[7] The submarine's captain presented an open letter to the actors and production team, and a group of officers and crew members presented another. In a later script, several scenes were cut, and the names of the crew changed at the request of the crew members and their families.

The most significant difference between the plot and the historical events is the scene that replaces an incident where the captain threw almost all the submarine's small arms overboard out of concern about the possibility of a mutiny; the film instead portrays an actual attempt at mutiny.

The Hotel-class submarine K-19 was portrayed in the film by the Juliett-class K-77, which was significantly modified for the role. Her Majesty's Canadian Submarine Ojibwa portrayed the Soviet Whiskey-class submarine S-270. HMCS Terra Nova portrayed USS Decatur. The Canadian Halifax Shipyards stood in for the Sevmash shipyard of northern Russia.

Klaus Badelt wrote the film's late-Romantic-styled score.

Reception

K-19: The Widowmaker received mixed reviews with a total of 60% positive reviews on Rotten Tomatoes. It is summarized as being "A gripping drama even though the filmmakers have taken liberties with the facts."[8]

When K-19: The Widowmaker was premiered in Russia in October 2002, 52 veterans of the K-19 submarine accepted flights to the Saint Petersburg premiere; despite what they saw as technical as well as historical compromises, they praised the film and in particular the performance of Harrison Ford.[9]

In his review, film critic Roger Ebert compared K-19: The Widowmaker to other classic films of the genre, "Movies involving submarines have the logic of chess: The longer the game goes, the fewer the possible remaining moves. 'K-19: The Widowmaker' joins a tradition that includes Das Boot and The Hunt for Red October and goes all the way back to Run Silent, Run Deep. The variables are always oxygen, water pressure and the enemy. Can the men breathe, will the sub implode, will depth charges destroy it?"[10]

References

Notes

- ↑ – The Widowmaker' (12A)." British Board of Film Classification, June 18, 2002. Retrieved: January 20, 2013.

- ↑ – The Widowmaker' (12A)." The Numbers. Retrieved: April 28, 2017.

- 1 2 "K-19 The Widowmaker (2002)." BoxOfficeMojo.com. Retrieved: July 3, 2016.

- ↑ Huchthausen 2002, p. 167.

- ↑ "K-19: The Widowmaker (2002)." DVDmg.com, March 14, 2009. Retrieved: July 3, 2016.

- ↑ "Hollywood's biggest names- Are they still worth their price?" EZ-Entertainment.net. Retrieved: July 3, 2016.

- ↑ Gentleman, Amelia. "Hollywood infuriates Russian veterans." The Guardian, February 23, 2001. Retrieved: July 3, 2016.

- ↑ "K-19: The Widowmaker Movie Reviews, Pictures". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 19 August 2009.

- ↑ Titova, Irina."K-19 Film Premieres at Mariinsky Theater." The St. Petersburg Times, 2002.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger. "K-19: The Widowmaker Movie Review (2002)." RogerEbert.com, July 19, 2003. Retrieved: July 3, 2016.

Bibliography

- Huchthausen, Peter. K-19, The Widowmaker: The Secret Story of The Soviet Nuclear Submarine. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic, 2002. ISBN 978-0-7922-6472-9.

- K-19, The Widowmaker: Handbook of Production Information. Los Angeles, California: Paramount Pictures, 2002.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: K-19: The Widowmaker |

- K-19: The Widowmaker at the TCM Movie Database

- K-19: The Widowmaker on IMDb

- K-19: The Widowmaker at AllMovie

- K-19: The Widowmaker at the American Film Institute Catalog

- K-19: The Widowmaker at Box Office Mojo

- K-19: The Widowmaker at Rotten Tomatoes

- K-19: The Widowmaker at Metacritic

- K-19: The Widowmaker at National Geographic