John Simon, 1st Viscount Simon

| The Right Honourable The Viscount Simon GCSI GCVO OBE PC | |

|---|---|

| |

| Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain | |

|

In office 10 May 1940 – 27 July 1945 | |

| Prime Minister | Winston Churchill |

| Preceded by | The Viscount Caldecote |

| Succeeded by | The Viscount Jowitt |

| Chancellor of the Exchequer | |

|

In office 28 May 1937 – 10 May 1940 | |

| Prime Minister | Neville Chamberlain |

| Preceded by | Neville Chamberlain |

| Succeeded by | Sir Kingsley Wood |

| Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs | |

|

In office 5 November 1931 – 7 June 1935 | |

| Prime Minister | Ramsay MacDonald |

| Preceded by | The Marquess of Reading |

| Succeeded by | Sir Samuel Hoare, Bt |

| Home Secretary | |

|

In office 7 June 1935 – 28 May 1937 | |

| Prime Minister | Stanley Baldwin |

| Preceded by | Sir John Gilmour, Bt |

| Succeeded by | Sir Samuel Hoare, Bt |

|

In office 27 May 1915 – 12 January 1916 | |

| Prime Minister | H. H. Asquith |

| Preceded by | Reginald McKenna |

| Succeeded by | Herbert Samuel |

| Attorney-General | |

|

In office 19 October 1913 – 25 May 1915 | |

| Prime Minister | H. H. Asquith |

| Preceded by | Sir Rufus Isaacs |

| Succeeded by | Sir Edward Carson |

| Solicitor-General | |

|

In office 7 October 1910 – 19 October 1913 | |

| Prime Minister | H. H. Asquith |

| Preceded by | Sir Rufus Isaacs |

| Succeeded by | Sir Stanley Buckmaster |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

John Allsebrook Simon 28 February 1873 Moss Side, Manchester, Lancashire, England |

| Died | 11 January 1954 (aged 80) |

| Political party | Liberal Party |

| Other political affiliations | National Liberal Party |

| Spouse(s) |

Ethel Venables (1899–1902; her death) Kathleen Rochard Manning (1917–1954; his death) |

| Children | 3 |

| Alma mater | Wadham College, Oxford |

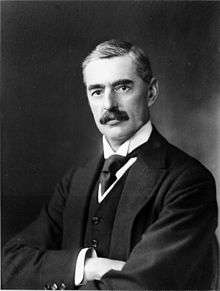

John Allsebrook Simon, 1st Viscount Simon, GCSI, GCVO, OBE, PC (28 February 1873 – 11 January 1954) was a British politician who held senior Cabinet posts from the beginning of the First World War to the end of the Second. He is one of only three people to have served as Home Secretary, Foreign Secretary and Chancellor of the Exchequer, the others being R. A. Butler and James Callaghan.

He also served as Lord Chancellor, the most senior position in the British legal system. Beginning his career as a Liberal (identified with the left-wing[1] and later the right-wing of the Party[2]), he joined the National Government in 1931, creating the Liberal National Party in the process. At the end of his career he was, essentially, a Conservative.

Background and education

Simon was born in a terraced house on Moss Side, Manchester, the eldest child and only son[3][4] of Edwin Simon (1843–1920) and Fanny Allsebrook (1846–1936).[5] His father was a Congregationalist minister like three of his five brothers and was pastor of Zion Chapel in Hulme District, Manchester; his mother was a farmer’s daughter and a descendant of Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury.[3]

Congregational Ministers were expected to move about the country.[6] Simon was educated at King Edward's School, Bath, as his father was President of Somerset Congregational Union.[3] He was then a scholar of Fettes College in Edinburgh[6][3] where he was Head of School and won many prizes.[7]

He failed to win a scholarship to Balliol College, Oxford, but won an open scholarship to Wadham College, Oxford.[3][7] He arrived at Wadham in 1892.[8] He achieved Seconds in Mathematics and Classical Moderations.[8] He campaigned for Herbert Samuel for South Oxfordshire in the 1895 election[8] and after two terms as Junior Treasurer became President of the Oxford Union in Hilary (spring) Term 1896,[3][8] Simon won the Barstow Law Scholarship and graduated with a first in Greats in 1896.[3][8]

Simon's attendance at Wadham overlapped with those of F. E. Smith, the cricketer C.B. Fry[3] and the journalist F. W. Hirst.[8] Smith, Fry and Simon played in the Wadham Rugby XV together.[9][8] Simon and Smith began a rivalry which lasted throughout their legal and political careers over the next thirty years. Simon was, in David Dutton's view, a finer scholar than Smith. Smith thought Simon pompous, while Simon, in the words of a contemporary, thought Smith excelled at "the cheap score".[8] A famous – although clearly untrue – malicious story had it that F. E. Smith and Simon had tossed a coin to decide which party to join.[10]

Simon was briefly a trainee leader writer for the Manchester Guardian under C. P. Scott.[9] Simon shared lodgings with Leo Amery whilst both were studying for the All Souls Fellowship (both were successful).[8] He became a Fellow of All Souls in 1897.[3]

Simon left Oxford at the end of 1898[3] and was called to the bar at the Inner Temple in 1899.[5] He was a pupil of A. J. Ram and then of Sir Reginald Acland.[3] Like many barristers, his career got off to a slow start: he earned a mere £27 in his first year at the Bar.[9] At first he earned some extra money by coaching candidates for the Bar exams.[8] As a barrister he relied on logic and reason rather than oratory and histrionics, and excelled at simplifying complex issues.[3] He was a brilliant advocate of complex cases before judges, although rather less so before juries.[11] Some of his work was done on the Western Circuit at Bristol. He worked exceptionally hard, often preparing his cases through the night several nights a week. His initial lack of connections made his eventual success at the Bar all the more impressive.[8]

Simon was widowed in 1902 (see below) and took solace in his work. He became a successful lawyer and in 1903 he acted for the British Government in the Alaska boundary dispute. Even three years after his wife's death, he spent Christmas Day 1905 alone, walking aimlessly in France.[3]

Before the First World War

Simon entered the House of Commons as a Liberal Member of Parliament (MP) for Walthamstow at the January 1906 general election. In 1908 he became a KC (senior barrister).[3] Simon and F. E. Smith became KCs simultaneously.[7] Simon annoyed Smith by not telling his rival in advance that he was applying for silk.[8]

In 1909 Simon spoke out strongly in Parliament in support of David Lloyd George's progressive "People's Budget".[12] He entered the Government on 7 October 1910 as Solicitor-General,[13] succeeding Rufus Isaacs, and was knighted later that month[14] as was usual for Government law officers at the time (Asquith brushed aside his objections).[15] At 37 he was the youngest solicitor-general since the 1830s.[3] In February 1911 he successfully prosecuted Edward Mylius for criminal libel for claiming that King George V was a bigamist.[3] As required by the law at the time, he resigned his Parliamentary seat and fought a by-election on appointment as Solicitor-General.[15]

He was honoured with the KCVO in 1911.[16] Asquith referred to him as "the Impeccable" for his intellectual self-assurance,[16] although after a series of social encounters, he wrote that "The Impeccable" was becoming "The Inevitable". [17]

Along with Rufus Isaacs, Simon represented the Board of Trade at the public inquiry into the sinking of the RMS Titanic in 1912; their close questioning of witnesses helped to prepare the way for improved maritime safety measures.[18] Unusually for a government law officer, he was active in partisan political debate.[15] When F. E. Smith first spoke from the Conservative front bench in 1912, Simon was put up next to oppose his old rival.[8] He was promoted on 19 October 1913 to Attorney-General,[3][19] again succeeding Isaacs. Unusually for an Attorney-General, he was made a full member of Cabinet (as Isaacs had been) rather than simply being invited to attend as required. He was already being tipped as a potential future Liberal Prime Minister.[3]

He was the leader of the (unsuccessful) Cabinet rebels against Winston Churchill's 1914 naval estimates. Asquith thought Simon had organised "a conclave of malcontents" (Lloyd George, Reginald McKenna, Samuel, Charles Hobhouse and Beauchamp). He wrote to Asquith that the "loss of WC, though regrettable, is not by any means the splitting of the party". Lloyd George referred to Simon as "a kind of Robespierre".[20]

Simon contemplated resigning in protest at the declaration of war in August 1914 but in the end changed his mind.[3] He was accused of hypocrisy, even though his position was not actually very different to that of Lloyd George.[6] He remained in the Cabinet after Asquith reminded him of his public duty and hinted at promotion. He damaged himself in the eyes of Hobhouse (Postmaster-General), Charles Masterman and the journalist C. P. Scott. Roy Jenkins believes Simon was genuinely opposed to war.[21]

Early in 1915 Asquith rated Simon as "equal seventh" in his score list of the Cabinet, after his "malaise of last autumn".[21]

First World War

On 25 May 1915, Simon became Home Secretary in H. H. Asquith's new coalition government. He declined an offer of the job of Lord Chancellor, as it would have meant going to the Lords and restricting his active political career thereafter.[3] As Home Secretary he satisfied nobody. He tried to defend the Union of Democratic Control against Edward Carson's attempt to prosecute them, but at the same time he tried to ban The Times and the Daily Mail for criticising the government's conduct of the war, but did not get Cabinet support.[22]

He resigned in January 1916 in protest against the introduction of conscription of single men, which he thought a breach of Liberal principles.[3] McKenna and Walter Runciman also opposed conscription but because they thought it would weaken British industry, and wanted Britain to concentrate her war effort on the Royal Navy and supporting the other Allies with finance.[22] In his memoirs Simon later admitted that his resignation from the Home Office had been a mistake.[23]

After Asquith's fall in December 1916, Simon remained in opposition as an Asquithian Liberal.[23]

Simon proved his patriotism by serving as an officer on Trenchard's staff in the Royal Flying Corps[3] for about a year starting in the summer of 1917.[23] Simon's duties included purchasing supplies in Paris – he married his second wife there towards the end of 1917.[24] Amidst questions as to whether it was appropriate for a serving officer to do so, Simon spoke in Trenchard’s defence in Parliament when Trenchard resigned as Chief of Air Staff after falling out with the President of the Air Council Lord Rothermere. Rothermere soon resigned but Simon was attacked in the Northcliffe Press (Northcliffe was Rothermere's brother).[25]

Simon lost his seat at Walthamstow, at the "Coupon Election" in 1918.[3] He lost by the large margin of over 4,000 votes.[23]

1920s

Out of Parliament

In 1919, he attempted to return to Parliament at the Spen Valley by-election. Lloyd George put up a coalition Liberal candidate in Spen Valley to keep Simon out[26] and was active behind the scenes trying to see him defeated.[27]

Although the Coalition Liberals, who had formerly held the seat, were pushed into third place, Simon came second; in the view of Maurice Cowling (The Impact of Labour 1920-4), his defeat by Labour marked the point at which Labour began to be seen as a serious threat by the older parties.

Deputy leader of the Liberals

In the early 1920s, he practised successfully at the Bar before being elected for Spen Valley at the general election in 1922, and from 1922 to 1924, he served as deputy leader of the Liberal Party (under Asquith).[28][29] In the early 1920s he spoke in the House of Commons about socialism, the League of Nations, unemployment and Ireland. He may well have hoped to succeed Asquith as Liberal leader. He retired temporarily from the Bar at this time.[30]

In October 1924 Simon moved the amendment which brought down the First Labour Government. At the ensuing general election the Conservatives were returned to power and the Liberal Party was reduced to a rump of just over 40 MPs. Although Asquith, who had lost his seat, remained Leader of the Party, Lloyd George was elected chairman of the Liberal MPs by 29 votes to 9. Simon abstained in the vote. Simon, who was increasingly anti-socialist and quite friendly to the Conservative leader Stanley Baldwin, clashed with Lloyd George. He stood down as deputy leader and went back to the Bar again.[26][30]

General Strike and Simon Commission

Unlike Lloyd George, Simon opposed the General Strike in 1926. On 6 May 1926, the fourth day of the Strike, he declared in the House of Commons that the General Strike was illegal.[26] He argued that the strike was not entitled to the legal privileges of the Trade Disputes Act 1906, and that the union bosses would be "liable to the utmost farthing" in damages for the harm they inflicted on businesses and for inciting the men to break their contracts of employment. Simon was highly respected as an authority on the law but was not popular and not seen as a political leader.[31]

Simon was at this time one of the highest-paid barristers of his generation, believed to earn between £36,000 and £70,000 per annum (around £2m–£3.5m at 2016 prices).[23][32] It seemed for a while that he might abandon politics altogether.[26] Simon spoke for Newfoundland in the Labrador boundary dispute with Canada, before announcing his permanent retirement from the Bar.[33]

From 1927 to 1931 he chaired the Indian Constitutional Development Committee, known as the Simon Commission on India's constitution.[34][26] His personality was already something of an issue: Neville Chamberlain wrote of him to the Viceroy of India Lord Irwin (12 August 1928): "I am always trying to like him, and believing I shall succeed when something crops up to put me off".[35][26] Dutton describes his eventual report as a "lucid exposition of the problems of the subcontinent in all their complexity". However, he had been hampered by the Inquiry’s terms of reference (no Indians were included on the committee) and his conclusions were overshadowed by the Irwin Declaration of October 1929, to which Simon was opposed, which promised India eventual dominion status.[34][26] Simon was awarded the GSCI 1930.[16]

Liberal National split and moving towards the Conservatives

Before serving on the Committee Simon had obtained a guarantee that he would not be opposed by a Tory candidate at Spen Valley at the election, and indeed he was never opposed by a Conservative ever again.[36] During the late 1920s and especially during the 1929-31 Parliament, in which Labour had no majority but continued in office with the help of the Liberals, Simon was seen as the leader of the minority of Liberal MPs who disliked Lloyd George's inclination to support Labour rather than the Conservatives. Simon still supported free trade during the 1929-31 Parliament.[26]

In 1930 Simon headed the official inquiry into the R101 airship disaster.[26]

In June 1931, before the formation of the National Government, Simon resigned the Liberal whip. In the September of that year Simon and his thirty or so followers became the Liberal Nationals (later renamed the "National Liberals") and increasingly aligned themselves with the Conservatives for practical purposes.[26][34] He was accused by Lloyd George of leaving "the slime of hypocrisy" as he crossed the floor (on another occasion Lloyd George is said to have commented that he had "sat on the fence so long the iron has entered into his soul", although the latter quote is harder to verify).[37]

1930s: the National Government

Foreign Secretary

Simon was not initially included in Ramsay MacDonald's National Government when it was formed in August 1931. He offered to give up his seat at Spen Valley to Ramsay MacDonald if he had trouble holding Seaham (MacDonald held the seat in 1931, but lost it in 1935).[38] On 5 November 1931 Simon was appointed Foreign Secretary when the National Government was reconstituted.[38][26] The appointment was at first greeted with acclaim.[26] Simon's National Liberals continued to support protectionism and Ramsay MacDonald's National Government after the departure of the mainstream Liberals under Herbert Samuel, who left the government in 1932 and formally went into Opposition in November 1933.[26]

Simon's tenure of office saw a number of important events in foreign policy, including the Japanese invasion of Manchuria (which had begun in September 1931, before he took office). Simon attracted particular opprobrium for his speech to the General Assembly of the League of Nations at Geneva on 7 December 1932 in which he failed to denounce Japan unequivocally.[26][39] Thereafter Simon was known as the "Man of Manchukuo" and was compared unfavourably to the young Anthony Eden, who was popular at Geneva.[40]

This period also saw the coming to power of Adolf Hitler in Germany in January 1933. Hitler immediately withdrew Germany from the League of Nations and announced a programme of rearmament, initially to give Germany armed forces commensurate with France and other powers. Simon did not foresee the sheer scale of Hitler's ambitions, but as Dutton points out neither did many others at the time.[26]

Simon's term of office also saw the failure of the World Disarmament Conference (1932-4). His contribution was not entirely in vain, as he proposed qualitative (seeking to limit or ban certain types of weapon) rather than quantitative (simple numbers of weapons) disarmament.[26]

Simon does not appear to have been considered for the post of Chancellor of Oxford University in succession to Viscount Grey in 1933, as he was then at the depth of his unpopularity as Foreign Secretary. Lord Irwin was elected, and as he lived until 1959 the job did not fall vacant again in Simon's lifetime.[41]

There was talk of Neville Chamberlain, who dominated the government's domestic policy, becoming Foreign Secretary, but this would have been intolerable to MacDonald, who took a keen interest in foreign affairs and wanted a leading non-Conservative in that role. In 1933 and late 1934 Simon was being criticised by both Austen and Neville Chamberlain, Anthony Eden, Lloyd George, Nancy Astor, David Margesson, Vincent Massey, Runciman, Jan Smuts and Churchill.[38]

Simon accompanied MacDonald to negotiate the Stresa Front with France and Italy in April 1935, although it was MacDonald who took the lead in the negotiations.[42] Simon himself did not think that Stresa would stop German rearmament, but he thought that it might be a useful deterrent against territorial aggression by Hitler.[43] The first stirrings of Italian aggression towards Abyssinia (modern Ethiopia) were also seen at this time. During Simon's tenure of the Foreign Office British defence strength was at its lowest point of the interwar period, severely limiting his freedom of action.[26]

Even Simon’s colleagues thought he had been a disastrous Foreign Secretary, "the worst since Æthelred the Unready" as one wag put it. He was better at analysing a problem than at concluding and acting.[26] Jenkins comments that he was a bad Foreign Secretary, in the view of his contemporaries and ever since and concurs that he was better at analysing than solving. Neville Chamberlain thought he always sounded as though he was speaking from a brief.[44][38] Simon’s officials despaired of him – he had few thoughts of his own, solutions were imposed on him by others and he defended them only weakly.[45] Leo Amery was a rare defender of Simon's record: in 1937 he recorded that Simon “really had been a sound foreign minister – and Stresa marked the nearest Europe has been to peace since 1914”.[46]

Home Secretary

Simon served as Home Secretary (in Stanley Baldwin's Third Government) from 7 June 1935 to 28 May 1937. This position was, in Dutton's view, better suited to his abilities than the Foreign Office had been.[26][47][26] He also became Deputy Leader of the House of Commons, on the understanding that the latter job would be given to Neville Chamberlain after the election (in the event, it did not).[48]

In 1935 Simon was the last Home Secretary to attend a Royal Birth (of the present Duke of Kent).[48] He passed the Public Order Act 1936, restricting the activities of Oswald Mosley's Blackshirts. He also played a key role behind the scenes in the Abdication Crisis of 1936.[26] He introduced the Factories Act 1937.[48]

Simon was devoted to his mother,[45] and wrote a well-received Portrait of My Mother in 1936 after her death.[16]

Chancellor of the Exchequer

Peace

In 1937 Neville Chamberlain succeeded Baldwin as Prime Minister. Simon succeeded Chamberlain as Chancellor of the Exchequer in his government (1937-40). He was raised to GCVO in 1937. As chancellor he tried to keep arms spending as low as possible, believing that a strong economy was the "fourth arm of defence".[16] In 1937 he presented a finance bill based on the budget which Chamberlain had drawn up before being promoted.[49]

In 1938 public expenditure passed the then unthinkable level of £1,000m for the first time. In the Spring 1938 budget Simon raised income tax from 5s to 5s 6d, and increased duties on tea and petrol.[49]

Simon had become a close political ally of Chamberlain.[5] He flattered Chamberlain a great deal. In autumn 1938 he led the Cabinet to Heston Airport to wish him God speed on his flight to meet Hitler, and he helped to persuade Chamberlain to make the "high" case for Munich, i.e. that he had achieved a lasting peace rather than limited potential damage.[50] He retained the support of Neville Chamberlain until around the middle of 1939.[49]

In the spring 1939 budget income tax was unchanged, and surtax was increased, as were indirect taxes on cars, sugar and tobacco. This was not a war budget even though it came after Hitler had broken the Munich agreement and occupied Prague.[49]

War

On 2 September 1939 Simon led a deputation of ministers to see Neville Chamberlain, to insist that Britain honour her guarantee to Poland and go to war if Hitler did not withdraw. He became a member of the small War Cabinet.[5]

On the outbreak of war sterling was devalued, with very little attention, from $4.89 to $4.03.[51] By the time of the emergency budget of September 1939 public expenditure passed £2,000m, income tax was increased from 5s 6d (27.5%) to 7s 6d (37.5%), whilst duties on alcohol, petrol and sugar were hiked, and a 60% tax on excess profits was introduced.[49]

Simon's political position weakened as he came to be seen as a symbol of foot-dragging and lack of commitment to total war. Along with Labour's dislike of Chamberlain he was used as an excuse by the Opposition parties for not joining the government on the outbreak of war. Archibald Sinclair, leader of the "official" Liberal Party, said that for over seven years Simon had been "the evil genius of British foreign policy". Hugh Dalton and Clement Attlee were very critical of Simon, as were many government backbenchers.[51]

Chamberlain privately told colleagues that he found Simon "very much deteriorated". Simon's position weakened after Churchill rejoined the Cabinet on the outbreak of war and got on surprisingly well with Chamberlain. Chamberlain toyed with the idea of replacing Simon with former Chancellor Reginald McKenna (then aged 76) or Lord Stamp, chairman of the LMS Railway who had a secret meeting at Number Ten about the job. Even Captain Margesson, the Chief Whip, fancied his chances as Chancellor.[51]

Simon's last budget in April 1940 saw public spending pass £2,700m, of which 46% was paid for from taxation and the rest from borrowing.[49] Simon's April 1940 budget kept income tax at 7s 6d – a Punch cartoon expressed a widely-held view that it should have been increased to 10s (50%). Tax allowances were increased. Postal charges were increased, as were charges on tobacco, matches and alcohol. Purchase tax, an ancestor of today’s VAT, was introduced.[51]

In April 1940 he rejected Maynard Keynes' idea of a forced loan (taxation disguised as a compulsory purchase of government securities). Keynes wrote a coruscating letter of rebuke to The Times. Simon found himself criticised, from opposite ends of the spectrum, by Leo Amery and Aneurin Bevan.[52]

Lord Chancellor

In May 1940, after the Norway Debate, Simon urged Chamberlain to stand firm as Prime Minister, although he offered to resign and take Samuel Hoare with him.[52]

By 1940, Simon, along with his successor as Foreign Secretary Sir Samuel Hoare, had come to be seen as one of the "Guilty Men" responsible for appeasement of the dictators, and like Hoare, his continued service in the War Cabinet was not regarded as acceptable in Churchill's new coalition. Hugh Dalton thought Simon "the snakiest of the lot".[53]

Simon became Lord Chancellor in Churchill's government although without a place on the War Cabinet. Attlee commented that he “will be quite innocuous” in the role.[52][54] On 13 May 1940 he was created Viscount Simon, of Stackpole Elidor in the County of Pembroke, a village from which his father traced descent.[16]

In Dutton's view, of all the senior positions which he held, this was the one for which he was most suited. As Lord Chancellor he delivered important judgements on the damages due for death caused by negligence, and on how the judge ought to direct the jury in a murder trial if a possible defence of manslaughter arose.[16] In 1943 alone he delivered 43 major judgements on complex cases. RVF Heuston (Lives of the Lord Chancellors) described him as a “superb” Lord Chancellor. Jenkins comments that this is even more impressive in that many senior judges had over twenty years’ experience at that level, whereas Simon had been retired from the Law since 1928.[55]

Simon interrogated Rudolf Hess after his flight to Scotland.[16][55] He also chaired the Royal Commission on the Birthrate.[55]

Simon's portrait (by Frank O. Salisbury, 1944) is in the National Portrait Gallery.[56]

In May 1945, after the end of the wartime Coalition, Simon continued as Lord Chancellor but was not included in the Cabinet of the short-lived Churchill caretaker ministry. After Churchill's election defeat in July 1945, Simon never held office again.[52]

Later life

Although he had won plaudits for his legal skills as Lord Chancellor, Clement Attlee declined to appoint him to the British delegation at the Nuremberg War Trials, telling him bluntly in a letter that his role in the pre-war governments made this unwise.[55] Simon remained active in the House of Lords and as a senior judge on the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. He wrote a well-regarded practitioners' text Simon on Income Tax in 1948.[16]

In 1948 Simon succeeded Lord Sankey as High Steward of Oxford University.[16] This position is often held by a distinguished Oxonian lawyer. Relations with his near-alcoholic wife were somewhat strained, and he increasingly spent his weekends at All Souls.[41] He was Senior Fellow of All Souls.[8]

Simon was a vigorous campaigner against socialism, across the country, in the general elections of 1945, 1950 and 1951.[41] Churchill blocked Simon, who had stepped down as leader of the National Liberals in 1940, from joining the Conservative Party.[16] Churchill was keen to lend Conservative support to the (official) Liberals, including his old friend Lady Violet Bonham Carter, but blocked a full merger between the Conservatives and the National Liberals, although a constituency-level merger was negotiated with the Conservative Party chairman Lord Woolton in 1947 (thereafter the National Liberals were increasingly absorbed into the Conservatives for practical purposes, formally merging in 1968).[41]

Although Simon was still physically and mentally vigorous (aged 78) when the Conservatives returned to power in 1951, Churchill did not offer him a return to the Woolsack, or any other office.[16] In 1952, Simon published his memoirs, Retrospect.[16] The quote "I so very tire of politics. The early death of too many a great man is attributed to her touch" is from Simon's memoir. Harold Nicolson reviewed the book as describing the "nectarines and peaches of office" as if they were "a bag of prunes".[11]

Viscount Simon died from a stroke on 11 January 1954. He was an atheist and was cremated in his Oxford robes.[16] His estate was valued for probate at £93,006 12s (around £2.3m at 2016 prices).[57][16][58] Despite his huge earnings at the Bar, he was not particularly greedy for money: he was generous to All Souls, to junior barristers and to the children of friends.[45]

His personal papers are preserved in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.[59]

Private life and personality

Simon married Ethel Mary Venables, a niece of the historian J R Green, on 24 May 1899 in Headington, Oxfordshire: she was later vice-principal of St Hugh's Hall, Oxford. They had three children: Margaret (born 1900, who later married Geoffrey Edwards), Joan (born 1901, who later married John Bickford-Smith) and John Gilbert, 2nd Viscount Simon (1902–1993). Ethel died soon after the birth of their son Gilbert, in September 1902.[3]

There are some suggestions that his first wife's death may have been caused by misguided use of homeopathic medicines, adding to Simon's guilt. Widowerhood, although not uncommon amongst politicians of the era may in Jenkins’ view have affected Simon's coldness and personality problems. He later apparently tried to persuade Mrs Ronnie Greville, the hostess of Polesden Lacey, to marry him.[9] Mrs Greville later claimed that he had told her he would marry the next woman he met.[60]

In 1917, in Paris, Simon married the abolition activist Kathleen Rochard Manning (1863/64–1955), a widow with one adult son, who had for a while been governess to his children.[3] Her social gaucheness and inability to play the part of a great lady caused embarrassment on the Simon Commission in the late 1920s, while Neville Chamberlain found her “a sore trial”. She had increasing health problems and “dr[ank] to excess” as she grew older.[60] Jenkins writes that she was tactless and by the late 1930s had become a virtual alcoholic, but that Simon treated her with "tolerance and kindness".[15] In 1938 Simon stepped down at Spen Valley and was selected as candidate for Great Yarmouth, as he needed a seat nearer London for the sake of his wife’s health (in the event he never stood for his new seat, remaining MP for Spen Valley until his elevation to the Lords in 1940).[60]

Simon bought De Lisle Manor in Fritwell, Oxfordshire in 1911 and lived there until 1933.[61]

Simon was neither liked nor trusted, and was never seriously considered for Prime Minister.[62] He possessed an unfortunately chilly manner, and from at least 1914 onwards, he had difficulty in conveying an impression that he was acting from honourable motives. His awkward attempts to strike up friendships with his colleagues (asking his Cabinet colleagues to call him "Jack" – only J.H. Thomas did so, whilst Neville Chamberlain settled on "John") often fell flat.[63] Jenkins likens him to the nursery rhyme character Dr Fell.[64] In the 1930s his reputation sank particularly low. Although Simon’s athletic build and good looks were remarked on even into old age, the cartoonist Low portrayed him with, in Low's own words, a "sinuous writhing body" to reflect his "disposition to subtle compromise".[16] Harold Nicolson, after Simon had grabbed his arm from behind to talk to him (19 October 1944), wrote pithily "God what a toad and a worm Simon is!"[65] Another anecdote, from the late 1940s, tells how the socialist intellectual G. D. H. Cole got into a third-class compartment on the train back from Oxford to London, to break off conversation with Simon; to his dismay Simon followed suit, only for both men to produce first class tickets when the inspector did his rounds.[66]

Cases

- Nokes v Doncaster Amalgamated Collieries Ltd [1940] AC 1014

References

- ↑ Keith Laybourn. "Fifty Key Figures in Twentieth-century British Politics". Books.google.co.uk. p. 209. Retrieved 2016-04-01.

- ↑ Jennings, Ivor (1961). Party Politics: Volume 2: The Growth of Parties. Cambridge University Press. p. 268. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Matthew 2004, p. 664.

- ↑ Jenkins 1999, p. 369, states that he was an only child.

- 1 2 3 4 Dutton, D. J. (2011) [2004]. "Simon, John Allsebrook, first Viscount Simon (1873–1954)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36098. (subscription required)

- 1 2 3 Jenkins 1999, p. 369.

- 1 2 3 Jenkins 1999, p. 370.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Dutton 1992, pp. 7–9.

- 1 2 3 4 Jenkins 1999, p. 371.

- ↑ Jenkins 1999, p. 370. Jenkins states that F. E. Smith and Simon both started at Wadham on the same day in 1891, which is not supported by David Dutton's more detailed biography.

- 1 2 Jenkins 1999, p. 367.

- ↑ "Finance Bill. (Hansard, 4 November 1909)". Hansard.millbanksystems.com. Retrieved 2016-04-01.

- ↑ "No. 28424". The London Gazette. 4 October 1910. p. 7247.

- ↑ "No. 28429". The London Gazette. 28 October 1910. p. 7611.

- 1 2 3 4 Jenkins 1999, p. 372.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Matthew 2004, p. 666.

- ↑ Jenkins 1999, p366

- ↑ Dutton 1992, p17

- ↑ "No. 28766". The London Gazette. 21 October 1913. p. 7336.

- ↑ Jenkins 1999, p373

- 1 2 Jenkins 1999, p. 374.

- 1 2 Jenkins 1999, p. 375.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jenkins 1999, p. 376.

- ↑ Dutton 1992, p45

- ↑ Dutton 1992, p. 46. Dutton states erroneously that Trenchard resigned as Commander of the Royal Flying Corps, the job he had performed on the Western Front in 1916–17

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Matthew 2004, p. 665.

- ↑ Jenkins 1999, p377

- ↑ "London Correspondence", Glasgow Herald, 24 November 1922, p.9

- ↑ Dutton 1992, p. 59.

- 1 2 Jenkins 1999, p. 378.

- ↑ Jenkins 1999, p379

- ↑ Compute the Relative Value of a U.K. Pound

- ↑ Jenkins 1999, p380

- 1 2 3 Jenkins 1999, p. 381.

- ↑ Jenkins, Roy The Chancellors (London: Macmillan, 1998), pp. 366–67.

- ↑ Jenkins 1999, pp. 377, 381.

- ↑ Jenkins 1999, p366

- 1 2 3 4 Jenkins 1999, p. 382.

- ↑ Douglas Reed, All Our Tomorrows (1942), p. 62: Geneva, 1931, "Sir John Simon congratulated by the Japanese emissary for presentation of Japan's case against China".

- ↑ Jenkins 1999, p384

- 1 2 3 4 Jenkins 1999, p. 392.

- ↑ Jenkins 1999, p384

- ↑ Dutton 1992, p220

- ↑ Jenkins 1999, p383

- 1 2 3 Jenkins 1999, p. 368.

- ↑ Dutton 1992, p207

- ↑ Rose, Kenneth (1983). King George V. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 402. ISBN 0-297-78245-2. OCLC 9909629.

It was thus that on the morning of 20 January 1936, three members of the Privy Council came down to Sandringham... MacDonald, the Lord President of the Council; Hailsham, the Lord Chancellor; and Simon, the Home Secretary.

- 1 2 3 Jenkins 1999, p. 385.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Jenkins 1999, p. 388.

- ↑ Jenkins 1999, p. 386.

- 1 2 3 4 Jenkins 1999, p. 389.

- 1 2 3 4 Jenkins 1999, p. 390.

- ↑ Jenkins 1999, p366

- ↑ At that time, besides being Minister in charge of the judiciary, the Lord Chancellor was also Speaker of the House of Lords and himself the most senior judge. He sat as one of the Law Lords, the senior judges who carried out the Judicial functions of the House of Lords. They were an ancestor body to today's Supreme Court of the United Kingdom

- 1 2 3 4 Jenkins 1999, p. 391.

- ↑ "NPG 5833; John Allsebrook Simon, 1st Viscount Simon – Portrait – National Portrait Gallery". Npg.org.uk. Retrieved 2016-04-01.

- ↑ Keith Laybourn. "British Political Leaders: A Biographical Dictionary". Books.google.co.uk. p. 298. Retrieved 2016-04-01.

- ↑ Compute the Relative Value of a U.K. Pound

- ↑ Langley, Helen (1979). "Catalogue of the papers of John Allsebrook Simon, 1st Viscount Simon, mainly 1894-1953". bodley.ox.ac.uk. Bodleian Libraries, Oxford. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 Dutton 1992, pp. 325–6.

- ↑ Lobel, Mary D. (ed.) (1959). Victoria County History: A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 6. pp. 134–46.

- ↑ Jenkins 1999, p365

- ↑ Jenkins, Roy The Chancellors (London: Macmillan, 1998), pp. 366.

- ↑ Jenkins 1999, p. 369: "I do not like thee Dr Fell, the reason why I cannot tell, but this I know and know full well, I do not like thee Dr Fell."

- ↑ Jenkins 1999, p366

- ↑ Jenkins, Roy The Chancellors (London: Macmillan, 1998), pp. 366–67.

Bibliography

- Dutton, David (1992). Simon: a political biography of Sir John Simon. London: Aurum Press. ISBN 1854102044.

- Dutton, D.J. (2011) [2004]. "Simon, John Allsebrook, first Viscount Simon (1873–1954)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36098. (subscription required)

- Jenkins, Roy (1999). The Chancellors. London: Papermac. ISBN 0333730585. (essay on Simon, pp365-92)

- Matthew (editor), Colin (2004). Dictionary of National Biography. 50. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198614111. (pp.663-6), essay on Simon written by David Dutton.

- Simon, John Simon, 1st Viscount (1952). Retrospect: the Memoirs of the Rt. Hon. Viscount Simon G.C.S.I., G.C.V.O. London: Hutchinson.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John Simon, 1st Viscount Simon. |

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by the Viscount Simon

- A Chessplaying Statesman

- Biography of Simon

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography website

- Portraits of John Simon, 1st Viscount Simon at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Newspaper clippings about John Simon, 1st Viscount Simon in the 20th Century Press Archives of the German National Library of Economics (ZBW)

.svg.png)