Jiexiu

| Jiexiu 介休市 | |

|---|---|

| County-level city | |

Xianshenlou | |

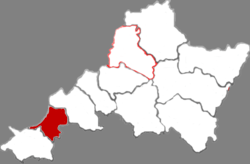

Jiexiu in Jinzhong | |

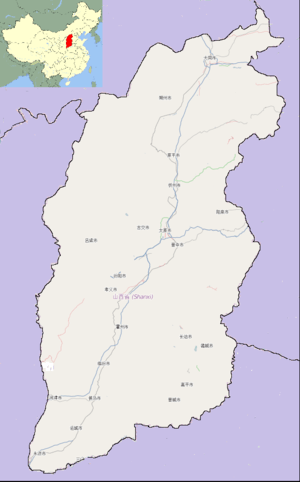

Jiexiu Location in Shanxi | |

| Coordinates: 37°01′37″N 111°55′01″E / 37.027°N 111.917°ECoordinates: 37°01′37″N 111°55′01″E / 37.027°N 111.917°E | |

| Country | People's Republic of China |

| Province | Shanxi |

| Prefecture-level city | Jinzhong |

| Area | |

| • Total | 744 km2 (287 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 756 m (2,480 ft) |

| Population () | |

| • Total | 370,000 |

| • Density | 500/km2 (1,300/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (China Standard) |

| Postal code | 031200 |

| Area code(s) | 0354 |

| Jiexiu | |||||||||

| Chinese | 介休市 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literal meaning | City of Jie Zitui's Eternal Rest | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Former names | |||||||||

| Mianshang | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 綿上 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 绵上 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Downy[lower-alpha 1] Heights | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Pingchang | |||||||||

| Chinese | 平昌 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Peaceful-&-Prosperous | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Jiezhou | |||||||||

| Chinese | 介州 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Jie Prefecture | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Jiexiu is a county-level city in the central part of Shanxi Province, China. It is under the administration of the prefecture-level city of Jinzhong and is located in the latter's western confines. It has jurisdiction over Mianshan, the site of the AAAAA-rated tourist attraction Mount Mian.

Names

The territory around Mt Mian was known as Mianshang under the Zhou.[1] By the Jin, the territory was known as Dingyang and the settlement at Jiexiu proper as Pingchang.[2] Under the Northern Wei (4th–5th century), both became known as Jiexiu Commandery.[2] Under the Tang, this was renamed Jiezhou AD 618–627.[2]

History

Mianshang was supposedly set apart by Duke Chong'er to endow sacrifices for his retainer Jie Zhitui c. 636 BC. The early histories state that Jie had loyally followed Chong'er in exile around China for 19 years but, when Chong'er was installed as duke of Jin by a Qin army, Jie had chosen to retire as a hermit rather than debase himself by asking for favors.[3][4][5][6][7] In time, this caused him to be seen as a Taoist immortal.[8] Later legend embellished the tale, having Jie save Chong'er from starvation[9] by cooking a soup made from meat from his own thigh[10][11] only to be killed when Chong'er listened to advice from Jin courtiers that the way to drive him out of the mountains was to light a forest fire.[12] The idea was that Jie's duty to his mother would overcome his pride and they would flee together;[13] instead, their corpses were found days later beneath a willow.[13][9][12] Temples were erected in Jie's honor[9] and, by the Han, the people of Shanxi tried to curry favor with his spirit by observing a Cold Food Festival in the dead of winter.[14][15][16] They ignored repeated attempts to ban it[15][17][18][19][20] although, as it moved to spring[21] and spread throughout China,[22][23] it eventually developed into the present-day Tomb-Sweeping Festival.[24][25]

During the Warring States Period, the area of Jiexiu was held by Zhao before its conquest by Qin.[26] Under the Han, it was part of Dingyang County (t 定陽縣, s 定阳县, Dìngyáng Xiàn) in Shang Commandery.[27] Jiexiu County was created under the Jin, but with its seat southeast of the current town.[2] The Northern Wei moved to the present location—then known as Pingchang—around AD 484 and made it the seat of a commandery.[2] This was made a county again by the Sui in 598, restored by the Tang in 617, and changed to a prefecture the next year.[2]

Climate

Jiexiu experiences a semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification BSk). Spring is dry, with frequent dust storms, followed by early summer heat waves. Summer tends to be warm to hot with most of the year's rainfall concentrated in July and August. Winter is long and cold, but dry and sunny. Because of the aridity, there tends to be considerable diurnal variation in temperature, except during the summer. The monthly 24-hour average temperature ranges from −4.4 °C (24.1 °F) in January to 23.9 °C (75.0 °F) in July, while the annual mean is 10.64 °C (51.2 °F). With monthly percent possible sunshine ranging from 49% in July to 60% in May, the city receives 2,425 hours of bright sunshine annually.

| Climate data for Jiexiu (1971−2000) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 2.5 (36.5) |

5.7 (42.3) |

12.0 (53.6) |

20.1 (68.2) |

25.5 (77.9) |

29.3 (84.7) |

30.1 (86.2) |

28.3 (82.9) |

24.1 (75.4) |

18.3 (64.9) |

10.2 (50.4) |

3.9 (39) |

17.5 (63.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −10 (14) |

−6.9 (19.6) |

−1.1 (30) |

5.5 (41.9) |

10.6 (51.1) |

15.0 (59) |

18.4 (65.1) |

16.9 (62.4) |

11.0 (51.8) |

4.8 (40.6) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

−7.4 (18.7) |

4.6 (40.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 3.7 (0.146) |

5.1 (0.201) |

14.1 (0.555) |

23.2 (0.913) |

32.0 (1.26) |

55.7 (2.193) |

111.7 (4.398) |

103.7 (4.083) |

55.9 (2.201) |

34.2 (1.346) |

11.4 (0.449) |

4.1 (0.161) |

454.8 (17.906) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 2.2 | 3.1 | 4.8 | 5.6 | 6.4 | 9.4 | 12.5 | 11.4 | 8.4 | 6.3 | 3.5 | 1.7 | 75.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 51 | 50 | 54 | 50 | 54 | 60 | 72 | 78 | 73 | 66 | 61 | 55 | 60 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 175.6 | 167.3 | 189.8 | 227.7 | 259.5 | 240.1 | 217.5 | 214.6 | 195.5 | 194.8 | 175.5 | 166.7 | 2,424.6 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 58 | 55 | 52 | 58 | 60 | 55 | 49 | 51 | 53 | 56 | 57 | 56 | 55 |

| Source: China Meteorological Administration | |||||||||||||

Government

Jiexiu administers an area divided into 5 subdistricts, 7 towns, and 3 townships:

| Subdistricts | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Simp. | Trad. | Pinyin |

| Beiguan | 北关街道 | 北關街道 | Běiguān Jiēdào |

| Xiguan | 西关街道 | 西關街道 | Xīguān Jiēdào |

| Dongnan | 东南街道 | 東南街道 | Dōngnán Jiēdào |

| Xinan | 西南街道 | 西南街道 | Xīnán Jiēdào |

| Beitan | 北坛街道 | 北關街道 | Běitán Jiēdào |

| Towns | |||

| Yi'an | 义安镇 | 義安鎮 | Yì'ānzhèn |

| Zhanglan | 张兰镇 | 張蘭鎮 | Zhānglánzhèn |

| Lianfu | 连福镇 | 連福鎮 | Liánfúzhèn |

| Hongshan | 洪山镇 | 洪山鎮 | Hóngshānzhèn |

| Longfeng | 龙凤镇 | 龍鳳鎮 | Lóngfèngzhèn |

| Mianshan | 绵山镇 | 綿山鎮 | Miánshānzhèn |

| Yitang | 义棠镇 | 義棠鎮 | Yìtángzhèn |

| Townships | |||

| Chengguan | 城关乡 | 城關鄉 | Chéngguānxiāng |

| Songgu | 宋古乡 | 宋古鄉 | Sònggǔxiāng |

| Sanjia | 三佳乡 | 三佳鄉 | Sānjiāxiāng |

Transport

Notes

References

Citations

- ↑ Xiao & al. (1996), p. 274.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Xiong (2016).

- ↑ Legge (1872), p. 191–2.

- ↑ Lü Buwei & al., "An Account of Jie", Master Lü's Spring & Autumn Annals [《呂氏春秋》, Lǚshì Chūnqiū] . (in Chinese)

- ↑ Knoblock & al. (2000), p. 263–4.

- ↑ Nienhauser & al. (2006), pp. 331–5.

- ↑ Sima Qian & al., "The Dynasty of Jin", Records of the Grand Historian [《史記》, Shǐjì], Vol. 39 . (in Chinese).

- ↑ Pseudo-Liu Xiang (ed.), "Jiezi Tui", Collected Biographies of the Immortals [《列仙傳》, Lièxiān Zhuàn] . (in Chinese)

- 1 2 3 Zhang (2015).

- ↑ Liao (1959), Bk. VIII, Ch. xxvii.

- ↑ Legge & al. (1891), Bk. XXIX, §10.

- 1 2 Huang & al. (2016), p. 82–3.

- 1 2 Lan & al. (1996).

- ↑ Pokora (1975), pp. 122 & 136–7.

- 1 2 Fan Ye, Book of the Later Han [《後漢書》, Hòu Hàn Shū], Vol. 61, §2024 . (in Chinese)

- ↑ Holzman (1986), p. 52–4.

- ↑ Li Fang, Imperial Reader of the Taiping Era [《太平御覽》, Tàipíng Yùlǎn], Vol. 28, §8a; Vol. 30, §6a–b; Vol. 869, §7b . (in Chinese)

- ↑ Fang Xuanling, Book of Jin [《晉書》, Jìn Shū], Vol. 105, §2749–50 . (in Chinese)

- ↑ Wei Shou, Book of Wei [《魏書》, Wèi Shū], Vol. 7A, §140, & Vol. 7B, §179 . (in Chinese)

- ↑ Holzman (1986), pp. 54–9.

- ↑ Holzman (1986), p. 69.

- ↑ Essential Techniques for the Welfare of the People [《齊民要術》, Qímín Yàoshù], Vol. 9, §521 (in Chinese)

- ↑ Holzman (1986), pp. 60–1.

- ↑ Zhang (2017).

- ↑ Wu (2014), p. 126

- ↑ Barbieri-Low & al. (2015), p. 1021.

- ↑ Barbieri-Low & al. (2015), pp. lvi, lxvi, & 1021.

Bibliography

- Barbieri-Low, Anthony J.; et al. (2015), Law, State, and Society in Early Imperial China, Sinica Leidensia, No. 247, Leiden: Brill .

- Confucius (1872), Legge, James, ed., The Ch‘un Ts‘ew, with the Tso Chuen, Pt. I, The Chinese Classics, Vol. V, Hong Kong: Lane, Crawford, & Co.

- Han Fei (1959), Liao Wên-kuei, ed., The Complete Works of Han Fei Tzŭ with Collected Commentaries, Oriental Series, Nos. XXV & XXVI, London: Arthur Probsthain .

- Holzman, Donald (June 1986), "The Cold Food Festival in Early Medieval China", Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Vol. 46 (No. 1), Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 51–79 .

- Huan Tan (1975), Pokora, T., ed., Hsin-lun and Other Writings, Michigan Papers in Chinese Studies, No. 20, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press .

- Huang, Julie Shiu-lan; et al. (2016), Along the River during the Qingming Festival, Cosmos Classics .

- Lan Peijin; et al. (1996), "Carrying His Mother into the Mountain[s]", Long Corridor Paintings at [the] Summer Palace, Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, p. 115 .

- Lü Buwei & al. (2000), Knoblock, John; et al., eds., The Annals, Stanford: Stanford University Press, ISBN 0-8047-3354-6 .

- Sima Qian & al. (2006), Nienhauser, William H. Jr.; et al., eds., The Grand Scribe's Records, Vol. V: The Hereditary Houses of Pre-Han China, Pt. 1, Bloomington: Indiana University Press .

- Wu Dongming (2014), A Panoramic View of Chinese Culture, Simon & Schuster .

- Xiao Tong; et al. (1996), Wen Xuan or Selections of Refined Literature, Vol. III, Princeton: Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-05346-4 .

- Xiong, Victor Cunrui (2016), "Jiexiu" & "Jiezhou", Historical Dictionary of Medieval China, Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, pp. 293–4 .

- Zhang Hui (27 Mar 2015), "Jiexiu: Doorway to the Past", Global Times, Beijing: People's Daily .

- Zhang Qian (1 April 2017), "Change of Weather, Rich Food Mark the Arrival of Qingming", Shanghai Daily, Shanghai: Shanghai United Media Group .

- Zhuang Zhou (1891), "The Writings of Kwang Tse, Pt. 2", in Legge, James; et al., The Texts of Taoism, Pt. II, The Sacred Books of China, Vol. VI, The Sacred Books of the East, Vol. XL, Oxford: Oxford University Press .

External links

- www.xzqh.org (in Chinese)