Japanese Canadian internment

In 1942, Japanese Canadian Internment occurred when over 22,000 Japanese Canadians from British Columbia were evacuated and interned in the name of ‘national security’. This decision followed the events of the Japanese invasions of Hong Kong and Malaya, the attack on Pearl Harbor, and the subsequent Canadian declaration of war on Japan during World War II. This forced relocation subjected many Japanese Canadians to government-enforced curfews and interrogations, job and property losses, and forced repatriation to Japan.[1]

Beginning after the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and lasting until 1949, Japanese Canadians were stripped of their homes and businesses and sent to internment camps and farms in the B.C. interior and across Canada.[2] The internment and relocation program was funded in part by the sale of property belonging to this forcefully displaced population, which included fishing boats, motor vehicles, houses, and personal belongings.[1]

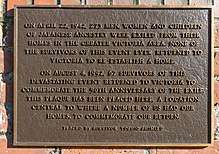

In August 1944, Prime Minister Mackenzie King announced that Japanese Canadians were to be moved east out of the British Columbia interior. The official policy stated that Japanese Canadians must move east of the Rocky Mountains or be repatriated to Japan following the end of the war.[3] By 1947, many Japanese Canadians had been granted exemption to this enforced no-entry zone. Yet it was not until April 1, 1949 that Japanese Canadians were granted freedom of movement and could re-enter the "protected zone" along B.C.'s coast.[4][5] On September 22, 1988, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney delivered an apology, and the Canadian government announced a compensation package.

Prewar history

Early settlement

Tension between Canadians and Japanese immigrants to Canada existed long before the outbreak of World War II. Starting as early as 1858 with the influx of Asian immigrants during the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush, beliefs and fears about Asian immigrants began to affect the populace in British Columbia. Canadian sociologist Forrest La Violette reported in the 1940s that these early sentiments had often been "...organized around the fear of an assumed low standard of living [and] out of fear of Oriental cultural and racial differences".[6] It was a common prejudiced belief within British Columbia that both Japanese and Chinese immigrants were stealing jobs away from white Canadians. Due to this fear, Canadian academic Charles H. Young concluded that many Canadians argued that "Oriental labour lowers the standard of living of White groups".[7] It was also argued that Asian immigrants were content with a lower standard of living. The argument was that many Chinese and Japanese immigrants in British Columbia lived in unsanitary conditions and were not inclined to improve their living space, thereby proving their inferiority and their unwillingness to become truly Canadian. Forrest E. La Violette refuted this claim by stating that while Japanese and Chinese immigrants did often have poor living conditions, both of the groups were hindered in their attempt to assimilate due to the difficulty they had in finding steady work at equal wages.[8]

In reference to Japanese Canadians specifically, human geographer Audrey Kobayashi argues that prior to the war, racism "had defined their communities since the first immigrants arrived in the 1870s."[9] Starting in 1877 with Manzo Nagano, a nineteen-year-old sailor who was the first Japanese person to officially immigrate to Canada, and entering the salmon-exporting business, the Japanese were quick to integrate themselves into Canadian industries.[10] Some Canadians felt that while the Chinese were content with being "confined to a few industries", the Japanese were infiltrating all areas of industry and competing with white workers.[11] This sense of unease among white Canadians was worsened by the growing rate of Japanese fishermen in the early 1900s. In 1919, 3,267 Japanese immigrants held fishing licenses and 50 percent of the total licenses issued that year were issued to Japanese fishermen. These numbers were alarming to Canadian fishermen who felt threatened by the growing number of Japanese competitors.[12] Japanese immigrants were also accused of being resistant to assimilation into Canadian society, because of Japanese-language schools, Buddhist temples, and low inter-marriage rates, among other examples. It was asserted that the Japanese had their own manner of living,[13] and that many who had become Canadian citizens did so to obtain fishing licences rather than out of a desire to become Canadian.[14] These arguments reinforced the idea that the Japanese remained strictly loyal to Japan.

1907 riots

The situation was exacerbated when, in 1907, the United States began prohibiting Japanese immigrants from accessing mainland America through Hawaii, resulting in a massive influx (over 7,000 as compared to 2,042 in 1906)[15] of Japanese immigrants into British Columbia. Largely as a result, on August 12, 1907, a group of Vancouver labourers formed an anti-Asiatic league, known as the Asiatic Exclusion League, with its membership numbering "over five hundred".[15] On September 7, 1907, some 5,000 people marched on Vancouver City Hall in support of the League, where they had arranged a meeting with presentations from both local and American speakers. By the time of the meeting, it was estimated that at least 25,000 people had arrived at Vancouver City Hall and, following the speakers, the crowd broke out in rioting, marching into Chinatown and Japantown. The rioters stormed through Chinatown first, breaking windows and smashing store fronts.[16] Afterwards, the rioters turned to the Japanese Canadian neighbourhood. Alerted by the previous rioting, Japanese Canadians in Little Tokyo were able to repel the mob without any serious injury or loss of life.[17] After the riot, the League and other nativist groups used their influence to push the government into an arrangement similar to the United States' Gentlemen's Agreement, limiting the number of passports given to male Japanese immigrants to 400 per year.[18] Women were not counted toward the quota, so "picture brides," women who married by proxy and immigrated to Canada to join (and in many cases, meet for the first time) their new husbands, became common after 1908. The influx of female immigrants — and soon after, Canadian-born children — shifted the population from a temporary workforce to a permanent presence, and Japanese-Canadian family groups settled throughout British Columbia and southern Alberta.[18]

World War I

During World War I, opinions of Japanese Canadians improved slightly. They were seen as an ally of the United Kingdom and some Japanese Canadians enlisted in the Canadian Forces. On the home front, many businesses began hiring groups that had been underrepresented in the workforce (including women, Japanese immigrants, and Yugoslavian and Italian refugees who had fled to Canada during the war) to help fill the increasing demands of Britain and its allies overseas. Businesses that had previously been opposed to doing so were now more than happy to hire Japanese Canadians as there was "more than enough work for all".[19] However, by the end of the war, soldiers returning home to find their jobs filled by others, including Japanese immigrants, were outraged. While they had been fighting in Europe, the Japanese had established themselves securely in many business and were now, more than ever, perceived as a threat to white workers. "'Patriotism' and 'Exclusion' became the watchwords of the day."[19]

Interwar years

While groups like the Asiatic Exclusion League and the White Canada Association viewed Japanese Canadians as cultural and economic threats, by the 1920s other groups had begun to come forward to the defence of Japanese Canadians, such as the Japan Society. In contrast to rival groups' memberships consisting of mostly labourers, farmers, and fishermen, the Japan Society was primarily made up of wealthy white businessmen whose goal was to improve relations between the Japanese and Canadians both at home and abroad. The heads of the organization included a "prominent banker of Vancouver" and a "manager of some of the largest lumbering companies in [British Columbia]."[20] They saw Japanese Canadians as being important partners in helping to open Japanese markets to businesses in British Columbia.

Despite the work of organizations like the Japan Society, many groups still opposed Japanese immigration to Canada, especially in B.C.'s fishing industry during the 1920s and 1930s. Prior to the 1920s, many Japanese labourers were employed as pullers, a job that required them to help the net men row the boats out to fish. The job required no license, so it was one of the few jobs for first-generation Japanese immigrants who were not Canadian citizens. In 1923, however, the government lifted a ban on the use of motorboats and required that pullers be licensed. This meant that first-generation immigrants, known as Issei, were unable to get jobs in the fishing industry, which resulted in large–scale unemployment among these Issei. Second-generation Japanese immigrants, known as Nisei, and who were Canadian citizens, began entering the fishing industry at a younger age to compensate for this, but even they were hindered as the increased use of motorboats resulted in less need for pullers and only a small number of fishing licenses were issued to Japanese Canadians.[21]

This situation escalated in May 1938 when the Governor General abolished the puller license entirely despite Japanese Canadians protests. This resulted in many younger Japanese Canadians being forced from the fishing industry, leaving Japanese Canadian net men to fend for themselves. Later that year, in August, a change to the borders of fishing districts in the area resulted in the loss of licenses for several Japanese-Canadian fishermen, who claimed they had not been informed of the change.[22] While these events did result in reduced competition from Japanese Canadians in the fishing industry, it created further tensions elsewhere.

Japanese Canadians had already been able to establish a secure position in many businesses during World War I, but their numbers had remained relatively small as many had remained in the fishing industry. As Japanese Canadians began to be pushed out of the fishing industry, they increasingly began to work on farms and in small businesses. This outward move into farming and business was viewed as more evidence of the economic threat Japanese Canadians posed towards white Canadians, leading to increased racial tension.[23]

In the years leading up to World War II, approximately 29,000 people of Japanese ancestry lived in British Columbia; 80% of these were Canadian nationals.[24] At the time, they were denied the right to vote and barred by law from various professions. Racial tensions often stemmed from the belief of many Canadians that all Japanese immigrants, both first-generation Issei and second-generation Nisei, remained loyal to Japan alone. Published in Maclean's Magazine, a professor at the University of British Columbia stated that the "Japanese in B.C. are as loyal to [Japan] as Japanese anywhere in the world."[25] Other Canadians felt that tensions, in British Columbia specifically, originated from the fact that the Japanese were clustered together almost entirely in and around Vancouver. As a result, as early as 1938, there was talk of encouraging Japanese Canadians to begin moving east of the Rocky Mountains,[26] a proposal that was reified during World War II.

The actions of Japan leading up to World War II were also seen as cause for concern. Japan withdrew from the League of Nations in 1934, ignored the naval ratio set up by the Washington Naval Conference of 1922, refused to follow the Second London Naval Treaty in 1936, and allied with Germany with the Anti-Comintern Pact. Because many Canadians believed that resident Japanese immigrants would always remain loyal to their home country, the Japanese in British Columbia, even those born and raised in Canada, were often judged for these militant actions taken by their ancestral home.[27]

World War II

When the Pacific War began, discrimination against Japanese Canadians increased. Following the Attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Japanese Canadians were categorized as enemy aliens under the War Measures Act, which began to remove their personal rights.[28] Starting on December 8, 1941, 1,200 Japanese-Canadian-owned fishing vessels were impounded as a "defence measure."[29] On January 14, 1942, the federal government passed an order calling for the removal of male Japanese nationals between 18 to 45 years of age from a designated protected area of 100 miles inland from the British Columbia coast. The federal government also enacted a ban against Japanese-Canadian fishing during the war, banned shortwave radios, and controlled the sale of gasoline and dynamite to Japanese Canadians.[30] Japanese nationals removed from the coast after the January 14 order were sent to road camps around Jasper, Alberta.

Three weeks later, on February 19, 1942, US President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which called for the removal of 110,000 people of Japanese ancestry from the American coastline. Anne Sunahara, a historian of internment, argues that "the American action sealed the fate of Japanese Canadians."[31] On February 24, the federal government passed order-in-council PC 1486, which allowed for the removal of "all persons of Japanese origin."[32] This order-in-council granted the Minister of Justice the broad powers of removing people from any protected area in Canada, but was meant for Japanese Canadians on the Pacific coast in particular. On February 25, the federal government announced that Japanese Canadians were being moved for reasons of national security.[33] In all, some 27,000 people were detained without charge or trial, and their property confiscated. Others were deported to Japan.[34]

However, not all Canadians believed that Japanese Canadians posed a threat to national security, including select senior officials of the RCMP, Royal Canadian Navy, and Department of Labour and Fisheries.[35] Notable individuals on the side of the Japanese Canadians included Hugh Llewellyn Keenleyside, Assistant Under-Secretary at External Affairs during the internment of Japanese Canadians. Anne Sunahara argues that Keenleyside was a sympathetic administrator who advocated strongly against the removal of Japanese Canadians from the BC coast. He unsuccessfully tried to remind other government officials of the distinction between Japanese foreign nationals and Canadian citizens in regards to personal and civil rights.[36]

Frederick J. Mead, RCMP Assistant Commissioner, also used his position to advocate for Japanese Canadians and mitigate government actions. Mead was given the task of implementing several federal policies, including the removal of Japanese Canadians from the "protected zone" along the coast in 1942. Mead attempted to slow down the process, allowing individuals and families more time to prepare by following the exact letter of the law, which required a complicated set of permissions from busy government ministers, rather than the spirit of quick removal it intended.[37]

However, it was not just government officials, but also private citizens, who were sympathetic to the Japanese-Canadian cause. Writing his first letter in January 1941, Captain V.C. Best, a Salt Spring Island resident, advocated against mistreatment of Japanese Canadians for over two years.[38] Best wrote to Keenleyside directly for much of that period, protesting anti-Japanese sentiment in the press, advocating for Japanese-Canadian enlistment in the armed forces, and, when the forced removal and internment of Japanese-Canadians was underway, the conditions Japanese-Canadians faced in internment camps.[39]

Mackenzie King

William Lyon Mackenzie King served his final term as Prime Minister between 1935 and 1948, at which point he retired from Canadian politics. He had served two previous terms as Prime Minister, but this period was perhaps his most well-known. His policies during this period included unemployment insurance and tariff agreements with the UK and the United States.[40]

Prime Minister King wrote in his diary daily for most of his life. These diary entries have provided historians with a sense of the thoughts and feelings King held during the war. Historian N.F. Dreisziger has written that "though he undoubtedly considered himself a man of humanitarian outlook, he was a product of his times and shared the values of his fellow Canadians. He was—beyond doubt—an anti-Semite, and shouldered, more than any of his Cabinet colleagues, the responsibility of keeping Jewish refugees out of the country on the eve of and during the war."[41]

Prior to the dropping of the atomic bombs on Japan, Prime Minister King was not considered a racist. He seemed concerned for humanity and was against the use of the atomic bomb and even its creation. When King learned of the estimated date of the bomb dropping, he wrote in his diary: "It makes one very sad at heart to think of the loss of life that it [the bomb] will occasion among innocent people as well as those that are guilty".[42] Historians, however, point to King's specific diary entry on August 6, 1945 when referring to King's racism toward the Japanese. On August 6, King wrote in his diary:

- "It is fortunate that the use of the bomb should have been upon the Japanese rather than upon the white races of Europe".[43]

Japanese Canadians serving in the war

For many Japanese Canadians, World War I provided an opportunity to prove their loyalty to Canada and their allies through military service in the hopes of gaining previously denied citizenship rights. In the early years of the war, however, the supply of enlisting men surpassed demand, so recruiting officers could be selective in who they accepted. However, large numbers of Japanese Canadians volunteered, as did members of other visible minorities like Black Canadians and First Nations, so the Canadian government proposed a compromise that, if enlisted, minorities could fight separately.[44] The Japanese Canadian community was very energetic on this front. The Canadian Japanese Association of Vancouver offered to raise a battalion in 1915 and, upon receiving a polite reply, proceeded to enlist and train 277 volunteers at the expense of the Japanese Canadian community.[45] This offer, however, was rejected by Prime Minister Robert Borden and his federal cabinet. Yet, by the summer of 1916, the death toll in the trenches had risen, creating a new demand for soldiers and an increased need for domestic labour, which meant that the recruitment of minorities was reconsidered. Under this new policy, Japanese Canadians were able to enlist individually by travelling elsewhere in Canada where their presence was deemed less of a threat.[46] By the end of World War I, 185 Japanese Canadians served overseas in 11 different battalions.[47]

During World War II, some of the interned Japanese Canadians were combat veterans of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, including several men who had been decorated for bravery on the Western Front. Despite the first iterations of veterans affairs associations established during World War II, fear and racism drove policy and trumped veterans' rights, meaning that virtually no Japanese-Canadian veterans were exempt from being removed from the BC coast.[48]

Small numbers of military-age Japanese-Canadian men were permitted to serve in the Canadian Army in the Second World War as interpreters and in signal/intelligence units.[49] By January 1945, several Japanese Canadian men were attached to British units in the Far East as interpreters and translators. In total, about 200 Canadian Nisei joined Canadian forces during World War II.[50]

Throughout the war, Canadians of "Oriental racial origin" were not called upon to perform compulsory military service.[49] Japanese Canadian men who had chosen to serve in the Canadian army during the war to in order to prove their allegiance to Canada were discharged only to discover they were unable to return to the BC coast, or unable to have their Canadian citizenship rights reinstated.[51]

Internment camps

The December 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor spurred prominent British Columbians, including members of municipal governments, local newspapers, and businesses to call for the internment of ethnic Japanese living in Canada under the Defence of Canada Regulations. In British Columbia, there were fears that some Japanese Canadians who worked in the fishing industry were charting the coastline for the Japanese Navy and spying on Canada's military. British Columbia borders the Pacific Ocean, and was therefore believed to be easily susceptible to enemy attacks from Japan. In total, 22,000 Japanese Canadians (14,000 of whom were born in Canada, including David Suzuki) were interned starting in 1942. Even though both the RCMP and the Department of Defence lacked proof of any sabotage or espionage, Prime Minister Mackenzie King decided to intern Japanese Canadian citizens based on speculative evidence.[52]

Widespread internment began on February 24, 1942 with an order-in-council passed under the Defence of Canada Regulations of the War Measures Act, which gave the federal government the power to intern all "persons of Japanese racial origin."[53] A 100-mile (160 km) wide strip along the Pacific coast was deemed "protected", and men of Japanese origin between the ages of 18 and 45 were removed.

Sugar beet farms, road work, and prisoner-of-war camps

Many of the Japanese nationals removed from the coast after January 14, 1942 were sent to road camps in the British Columbia interior or sugar beet projects on the Prairies, such as in Taber, Alberta. Despite the 100-mile quarantine, a few Japanese Canadian men remained in McGillivray Falls, which was just outside the protected zone. However, they were employed at a logging operation at Devine (near D'Arcy in the Gates Valley), which was in the protected zone but without road access to the coast. Japanese Canadians interned in Lillooet Country found employment within farms, stores, and the railway.[54]

The Liberal government also deported able-bodied Japanese-Canadian labourers to camps near fields and orchards, such as the Okanagan Valley in British Columbia. The Japanese-Canadian labourers were used as a solution to a shortage of farm workers.[55] This obliterated any Japanese competition in the fishing sector. During the 1940s, the Canadian government created policies to direct Chinese, Japanese, and First Nations into farming, and other sectors of the economy that "other groups were abandoning for more lucrative employment elsewhere".[56]

The forced removal of many Japanese-Canadian men to become labourers elsewhere in Canada created confusion and panic among families, causing some men to refuse orders to ship out to labour camps. On March 23, 1942, a group of Nisei refused to be shipped out and so were sent to prisoner-of-war camps in Ontario to be detained.[57] The Nisei Mass Evacuation Group was formed to protest family break-ups and lobbied government organizations on the topic. However, their attempts were ignored and members of the group began going underground, preferring to be interned or sent to Ontario rather than join labour groups.[58]

By July 1942, after strikes occurred within the labour camps themselves, the federal government made a policy to keep families together in their removal to internment camps in the BC interior or sugar beet farms across the prairies.[59]

"Self-supporting projects"

In early March, all ethnic Japanese people were ordered out of the protected area, and a daytime-only curfew was imposed on them. Various camps in the Lillooet area and in Christina Lake were formally "self-supporting projects" (also called "relocation centres") which housed selected middle- and upper-class families and others not deemed as much of a threat to public safety.[54][60][61]

Internment camps

Before being sent off to road camps, sugar beet farms, or prisoner-of-war camps, many Japanese-Canadian men and their families were processed through Hastings Park in Vancouver, BC. Many of the men were separated from their families and sent into the B.C. interior or across Canada, but most women and children stayed in the park until they were sent to internment camps in the interior or decided as a family to join the sugar beet farms in the prairies.[62]

Effects of internment camps on women and children

Japanese-Canadian women and children faced a specific set of challenges that greatly affected their way of life and broke down the social and cultural norms that had developed. Whole families were taken from their homes and separated from each other. Husbands and wives were almost always separated when sent to camps and, less commonly, some mothers were separated from their children as well. Japanese-Canadian families typically had a patriarchal structure, meaning the husband was the centre of the family. Since husbands were often separated from their families, wives were left to reconfigure the structure of the family and the long-established divisions of labour that were so common in the Japanese-Canadian household.[63]

Life after internment

Oftentimes after internment, families could not be reunited. Many mothers were left with children, but no husband. Furthermore, communities were impossible to rebuild. The lack of community led to an even more intensified gap between the generations. Children had no one with whom to speak Japanese with outside the home and as a result they rarely learned the language fluently. This fracturing of community also led to a lack of Japanese cultural foundation and many children lost a strong connection with their culture. Mothers had also learned to be bolder in their own way and were now taking on wage-earning jobs, which meant that they had less time to teach their children about Japanese culture and traditions. The internment camps forever changed the way of Japanese-Canadian life.[64]

Camp conditions

Many Canadians were unaware of the living conditions in the internment camps. The Japanese Canadians who resided within the camp at Hastings Park were placed in stables and barnyards, where they lived without privacy in an unsanitary environment.[65] Kimiko, a former internee, attested to the "intense cold during the winter" and her only source of heat was from a "pot-bellied stove" within the stable.[66] General conditions were poor enough that the Red Cross transferred fundamental food shipments from civilians affected by the war to the internees.[67]

Some internees spoke out against their conditions, often complaining to the British Columbia Security Commission directly whenever possible. In one incident, fifteen men who had been separated from their families and put to work in Slocan Valley protested by refusing to work for four days straight. Despite attempts at negotiation, the men were eventually informed that they would be sent to the Immigration Building jail in Vancouver for their refusal to work.[68] Their mistreatment caused several of the men to begin hoping that Japan would win the war and force Canada to compensate them.[69]

Tashme, a camp on Highway 3 just east of Hope, was notorious for the camp's harsh conditions and existed just outside the protected area. Other internment camps, including Slocan, were in the Kootenay Country in southeastern British Columbia.[70] Leadership positions within the camps were only offered to Nisei, or Canadian-born citizens of Japanese origin, thereby excluding Issei, the original immigrants from Japan.

The internment camps in the B.C. interior were often ghost towns with little infrastructure to support the influx of people. When Japanese Canadians began arriving in the summer and fall of 1942, any accommodations given were shared between multiple families and many had to live in tents while shacks were constructed in the summer of 1942.The shacks were small and built with damp, green wood. When winter came, the wood made everything damp and the lack of insulation meant that the inside of the shacks often froze during the night.[71]

Very little was provided for the internees – green wood to build accommodation and a stove was all that most received. Men could make some money in construction work to support their families, but women had very few opportunities. Yet, finding work was almost essential since interned Japanese Canadians had to support themselves and buy food using the small salaries they had collected or through allowances from the government for the unemployed. The relief rates were so low that many families had to use their personal savings to live in the camps.[71]

By the spring of 1943, however, some conditions began to change as Japanese Canadians in the camp organized themselves. Removal from the coast to ghost towns had been done based location, so many communities moved together and were placed in same camp together. This preserved local communal ties and facilitated organizing and negotiating for better conditions in the camp.[71]

Camp locations

- Camps and relocation centres in the Kootenay region of British Columbia

- Bay Farm

- Greenwood

- Kaslo

- Lemon Creek

- New Denver

- Popoff

- Rosebery

- Sandon

- Slocan City

- Camps and relocation centres elsewhere in British Columbia

- Camps and relocation centres elsewhere in Canada

Restriction of property rights

Those living in "relocation camps" were not legally interned—they could leave, so long as they had permission—however, they were not legally allowed to work or attend school outside the camps.[73] Since the majority of Japanese Canadians had little property aside from their (confiscated) houses, these restrictions left most with no opportunity to survive outside the camps.[73]

It was the hope of the Canadian government that selling all of the Japanese Canadians' personal possessions and property would deter them from returning to British Columbia.[74]

Prime Minister King issued a ruling that all property would be removed from Japanese Canadian inhabitants. They were made to believe that their property would be held in trust until they had resettled elsewhere in Canada.[75]

Dispossession began with the seizure and forced sale of Japanese-Canadian fishing vessels in December 1941. After their seizure, the boats sat in disrepair for several months before being sold by the "Japanese Fishing Vessel Disposal Committee" at below-market prices.[76]

With this precedent set, B.C. politician Ian Mackenzie, federal Minister of Pensions and Health, wanted to ensure that Japanese Canadians never returned home and achieved this by selling Japanese Canadian farms and property as cheaply as possible.[74] In his mind, this would stop Japanese Canadians from returning to the coast after the war and would provide farms for the Veterans Land Act program, a program to resettle World War II veterans after the war.[77]

In 1943, the Canadian "Custodian of Enemy Property" liquidated all possessions belonging to the 'enemy aliens'. The Custodian of Enemy Property held auctions for these items, ranging from farm land, homes, and clothing. Japanese Canadians lost their fishing boats, bank deposits, stocks, and bonds; all items that had provided them with financial security.[78] Japanese Canadians protested that their property was sold at prices far below the fair market value at the time.[79] Prime Minister King responded to the objections by stating that the "Government is of the opinion that the sales were made at a fair price."[80] In all, 7,068 pieces of property, personal and landholdings alike, were sold for a total of $2,591,456.[48]

As well, robberies against businesses in Japantown rose after Pearl Harbor was bombed. At least one person died during a botched robbery.[81][82]

Confinement in the internment camps transformed the citizenship of many Japanese Canadians into an empty status and revoked their right to work.

Fishing boats

There were some economic benefits that came with the internment of Japanese Canadians. Specifically, white fishermen directly benefited due to the impounding of all Japanese-Canadian-owned fishing boats. Fishing for salmon was a hotly contested issue between the white Canadians and Japanese Canadians. In 1919, Japanese Canadians received four thousand and six hundred of the salmon-gill net licences, representing roughly half of all of the licences the government had to distribute. In a very public move on behalf of the Department of Fisheries in British Columbia, it was recommended that in the future Japanese Canadians should never again receive more fishing licences than they had in 1919 and also that every year thereafter that number be reduced. These were measures taken on behalf of the provincial government to oust the Japanese from salmon fishing. The federal government also got involved in 1926, when the House of Commons’ Standing Committee on Fisheries put forward suggestions that the number of fishing licences issued to Japanese Canadians be reduced by ten percent a year, until they were entirely removed from the industry by 1937. Yet, the reason the government gave for impounding the few remaining and operating Japanese-Canadian fishing boats was that the government feared these boats would be used by Japan to mount a coastal attack on British Columbia.

Many boats belonging to Japanese Canadians were damaged, and over one hundred sank.[73] A few properties owned by Japanese Canadians in Richmond and Vancouver were vandalized, including the Steveston Buddhist Temple.

Other property

The dispossession and liquidation of Japanese-Canadian property began in April 1942, when Ian Mackenzie asked the head of the Soldier Settlement Board, Thomas A. Crerar, and administrative head Gordon Murchison, to look into taking over Japanese Canadian farms for the Veteran’s Land Act program, which was not yet put into law.[77] They undertook a survey of the farms, but their survey metrics were flawed. They used measures from the Depression Era, when property values were low, did not take into account current crops or other land uses, and discounted the value of buildings by 70%.[77] In June 1942, Order in Council PC 5523 authorized Crerar to buy or lease Japanese Canadian farms without consulting their owners. Because of this, 572 farms were sold for $841,225, substantially less than their assessed value of $1,239,907.[83]

What started with the sale of farms soon expanded to include the sale of residential properties. In November 1942, the Custodian of Enemy Property, which already controlled most Japanese-Canadian property, began hinting towards obtaining the right to sell the property, not just administer it. This idea was well received by the Department of Labour, who were unsure how to pay for Japanese Canadian internment; selling their property would help Japanese Canadians pay for their own detention.[84]

Separately, the City of Vancouver also pushed for the sale of Japanese Canadian properties in the Powell Street "ghetto" to allow for redevelopment in the area. What began with discussions in the summer of 1942 about city-level urban renewal was quickly co-opted by the federal government in an attempt to sell all Japanese-Canadian properties, far beyond what the City of Vancouver had initially suggested.[85][86]

On January 11, 1943, the Cabinet Committee on Japanese Problems recommended the sale of urban and rural Japanese-Canadian properties, arguing that it would be safeguarding them and that it would be in the Japanese-Canadian owners’ best interest to sell because the value of their properties would go down.[87]

On January 23, 1943, an Order in Council was passed by the federal government that gave the Custodian of Enemy Property the right to sell Japanese Canadian property without the owner’s consent, and by March, 1943, the full dispossession of all property began.[88]

Japanese Canadians tried to resist the forced sale of their properties. At an internment camp in Kaslo, BC, Japanese Canadian property owners formed the "Japanese Property Owners’ Association" with branches at other internment camps across B.C.[89] Their aim was to explore the possibilities for legal action, and in May 1944 they launched a claim with the Exchequer Court in Ottawa.[90] The claim was delayed in courts until August 28, 1947, and in the meantime, approximately $11.5 million worth of Japanese Canadian property had been sold for just over $5 million.[90][91]

For those Japanese Canadians living in the internment camps, the forced sale of their properties meant they now had less money and resources. They were not receiving any rental income from their properties, and the Custodian of Enemy Property took control of the funds resulting from property sales. The Custodian did not provide interest on the funds, and restricted withdrawals from the funds held in their possession.[91] What little funds Japanese Canadians were able to receive went to supporting themselves and their families in the camps, often helping those who could not work or were not able to live off inadequate government subsidies. As a result, many families and single men began leaving B.C. in search of employment elsewhere.[92]

Bird Commission

In 1946 and 1947, pressure began to build for the federal government to address the forced sale of Japanese Canadian property. In 1947, representatives from the Co-operative Committee on Japanese Canadians and the Japanese Canadian Committee for Democracy asked the federal government’s Public Accounts Committee to launch a Royal Commission to look into the losses associated with the forced sales. In June 1947, the Public Accounts Committee recommended that a commission be struck to examine the claims of Japanese Canadians living in Canada (many Japanese Canadians had been deported to Japan during the war) for losses resulting from receiving less than the fair market value of their property.[93]

A Royal Commission was set up later that year, headed by Justice Henry Bird, with terms of reference that placed the onus on the Japanese-Canadian claimant to prove that the Custodian of Enemy Property was negligent in the handling of their property. The terms of reference soon expanded to also include the sale of property below market value, but no cases were accepted that dealt with issues outside the control of the Custodian of Enemy Property.[94]

In late 1947, Bird began to hear individual claims, but by 1948 it became clear to the commission that the magnitude of claims and amount of property in dispute could take years to settle and become very expensive for claimants because of legal fees. Thus, in the spring of 1949, the Bird Commission adopted a category formula that set out certain reimbursement percentages for each category of claim, except for unusual circumstances.[95]

The commission concluded in 1950, and the report stated that:[96]

- The commission found that claims relating to fishing boats should receive 12.5% of sale price as compensation and receive the Custodian of Enemy Property’s 13.5% commission. Out of the 950 fishing boats seized in 1941, only 75 claims were processed by the Bird Commission.

- Claims relating to fishing nets and gear should receive 25% of sale price.

- Claims relating to cars and trucks should receive 25% of sale price.

- Claims relating to the sale of personal belongings were deemed mostly worthless and claimants received the Custodian of Enemy Property’s commission plus 6.8% of the sale price.

- Very few claims relating to personal real estate received any form of compensation because the Commission concluded that most were sold for fair market value.

- Farmers whose property had been seized by the Soldier Settlement Board received $632,226.61 combined, despite that being only half of their total claim.

The top monetary award was $69,950 against a $268,675 claim by the Royston Lumber Company, and the smallest claim was $2.50 awarded to Ishina Makino for a claim against a car.[97] After the report was released, the CCJC and National Japanese Canadian Citizens’ Association wanted to push for further compensation, however when claimants accepted their Bird Commission reimbursements, they had to sign a form agreeing that they would not press any further claims.[98]

By 1950, the Bird Commission awarded $1.3 million in claims to 1,434 Japanese Canadians. However, it only accepted claims based on loss of property, refusing to compensate for wrongdoing in terms of civil rights, damages due to loss of earnings, disruption of education, or other factors.[73] The issue of Japanese Canadian losses was not revisited in-depth until the Price Waterhouse study in 1986.

Resettlement and repatriation

| “ | "It is the government’s plan to get these people out of B.C. as fast as possible. It is my personal intention, as long as I remain in public life, to see they never come back here. Let our slogan be for British Columbia: ‘No Japs from the Rockies to the seas.'" | ” |

| — Ian Mackenzie, Minister of Pensions[99] | ||

British Columbian politicians began pushing for the permanent removal of Japanese Canadians in 1944. By December, U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt had announced that Japanese Americans would soon be allowed to return to the West Coast, and pressure to publicize Canada's plans for their interned Japanese Canadians was high. Officials created a questionnaire to distinguish "loyal" from "disloyal" Japanese Canadians and gave internees the choice to move east of the Rockies immediately or be "repatriated" to Japan at the end of the war. Some 10,000 Japanese Canadians, unable to move on short notice or simply hesitant to remain in Canada after their wartime experiences, chose deportation.[18] The rest opted to move east, many to the city of Toronto, where they could take part in agricultural work. By 1947, most Japanese Canadians not slated for deportation had moved from British Columbia to the Toronto area, where they often become farmhands or took on similar labour jobs as they had done before.[100] Several Japanese Canadians who resettled in the east wrote letters back to those still in British Columbia about the harsh labour conditions in the fields of Ontario and the prejudiced attitudes they would encounter.[101] White-collar jobs were not open to them, and most Japanese Canadians were reduced to "wage-earners".[101]

When news of Japan's surrender in August 1945 reached the internment camps, thousands balked at the idea of resettling in the war-torn country and attempted to revoke their applications for repatriation.[18] All such requests were denied, and deportation to Japan began in May 1946. While the government offered free passage to those who were willing to be deported to Japan,[80] thousands of Nisei born in Canada were being sent to a country they had never known. Families were divided, and being deported to a country that had been destroyed by bombs and was now hunger-stricken due to the war.[102] Public attitudes towards the internees had softened somewhat since the start of the war, and citizens formed the Cooperative Committee on Japanese Canadians to protest the forced deportation. The government relented in 1947 and allowed those still in the country to remain; however, by this time 3,964 Japanese Canadians had already been deported to Japan.[18][103]

Postwar history

Following public protest, the order-in-council that authorized the forced deportation was challenged on the basis that the forced deportation of Japanese Canadians was a crime against humanity and that a citizen could not be deported from his or her own country. The federal cabinet referred the constitutionality of the order-in-council to the Supreme Court of Canada for its opinion. In a five to two decision, the Court held that the law was valid. Three of the five found that the order was entirely valid. The other two found that the provision including both women and children as threats to national security was invalid. The matter was then appealed to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in Britain, at that time the court of last resort for Canada. The Judicial Committee upheld the decision of the Supreme Court. In 1947, due to various protests among politicians and academics, the Federal Cabinet revoked the legislation to repatriate the remaining Japanese Canadians to Japan.[104] It was only in April 1949 that all restrictions were lifted from Japanese Canadians.

Issues surrounding the internment of Japanese Canadians also led to changes to Canadian immigration policy, with the legislation gaining momentum after a statement made by the Prime Minister on May 1, 1947:

"There will, I am sure, be general agreement with the view that people of Canada do not wish, as a result of mass immigration, to make a fundamental alteration in the character of our population. Large-scale immigration from the orient would change the fundamental composition of the Canadian population ... The government, therefore, has no thought of making any changes in immigration regulations which would have consequences of the kind.[105]

This reform to immigration policy was deemed necessary on two grounds: the inevitable post-war crisis of displaced persons from Europe, and the growing number of Canadians who wished to bring family to Canada following the war—the large number of war brides being the chief concern on this front. Mackenzie King believed that Canada was under no legal obligations to make such accommodations, only a moral obligation. During this time, the Canadian government also made provisions to begin the repeal of the discriminatory Chinese Immigration Act.[105]

Redress

In the postwar years, Japanese Canadians had organized the Japanese Canadian Committee for Democracy, which later became the National Association of Japanese Canadians (NAJC). In 1977, during the celebration of the 100th anniversary of the arrival of the first Japanese immigrant to Canada, discussions of redress began to have an effect. Meeting in basements and coffee houses, Japanese Canadian anger arose again, and the sense of shame was gradually replaced by one of indignation.[34] This encouraged Japanese Canadians to fight for their rights and to gain compensation for what they had been through during the war.

In 1983, the NAJC mounted a major campaign for redress which demanded, among other things, a formal government apology, individual compensation, and the abolition of the War Measures Act.[73]

| “ | "Born in Canada, brought up on big-band jazz, Fred Astaire and the novels of Henry Rider Haggard, I had perceived myself to be as Canadian as the beaver. I hated rice. I had committed no crime. I was never charged, tried or convicted of anything. Yet I was fingerprinted and interned." | ” |

| — Ken Adachi[106] | ||

To help their case, the NAJC hired Price Waterhouse to examine records to estimate the economic losses to Japanese Canadians resulting from property confiscations and loss of wages due to internment. Statisticians consulted the detailed records of Custodian of Enemy Property, and in their 1986 report, valued the total loss to Japanese Canadians at $443 million (in 1986 dollars).[73]

On September 22, 1988, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney delivered an apology, and the Canadian government announced a compensation package, one month after President Ronald Reagan made similar gestures in the United States. The package for interned Japanese Canadians included $21,000 to each surviving internee, and the re-instatement of Canadian citizenship to those who were deported to Japan.[107] Following Mulroney's apology, the Japanese Canadian Redress Agreement was established in 1988, along with the Japanese Canadian Redress Foundation (JCRF) (1988-2002), in order to issue redress payments for internment victims, with the intent of funding education.[108] However, of the $12 million community fund, it was agreed upon by the JCRF board members that $8 million would go towards building homes and service centres for Issei senior citizens. Due to the fact that Issei had been stripped of their wealth, property, and livelihoods during internment, it was a main concern of the JCRF to provide aid to their community elders.[108] Nothing was given for those that had been interned and died before compensation was paid out.

Following redress, there was increased education in the public education system about internment.[109] By utilizing this outlet, Canadians were able to confront the social injustice of Japanese Internment in a way that accepts those affected and aids in creating a community that values social reconstruction, equality, and fair treatment.[109] Public education provides an outlet for wronged individuals to share their stories and begin to heal, which is a necessary process to repair their trust in a government that can care for and protect their individual and cultural rights.[109] "The first step to recognition of Japanese-Canadian redress as an issue for all Canadians was recognition that it was an issue for all Japanese Canadians, not in the interests of retribution for their 'race', nor only in the interests of justice, but in recognition of a need to assert principles of human rights so that racism and other forms of discrimination might be challenged."[107] The question of whether Canada and Japanese Canadians can truly move on from the past has been explored in first-hand accounts and literature, such as Joy Kogawa's Obasan[110]

The Nikkei Memorial Internment Centre in New Denver, British Columbia, is an interpretive centre that honours the history of interned Japanese Canadians, many of whom were confined nearby.[111]

See also

- Head tax (Canada)

- Japanese American Internment

- Masumi Mitsui

- Ukrainian Canadian Internment

- Social exclusion in Canada

- Obasan

References

- 1 2 Sugiman (2004), p. 360

- ↑ Sunahara, Ann (1981). The Politics of Racism: The Uprooting of Japanese Canadians during the Second World War. Toronto: J. Lorimer. pp. 66, 76.

- ↑ Roy (2002), p. 70

- ↑ Roy (2002), p. 76

- ↑ Adachi, Ken (1976). The Enemy That Never Was: A History of the Japanese Canadians. Toronto: McClelland and Steward. pp. 343–344.

- ↑ La Violette (1948), p. 4

- ↑ Young (1938), p. xvi

- ↑ La Violette (1948), pp. 5–6

- ↑ Kobayashi, Audrey (Fall 2005). "The Uprooting of Japanese Canadians and Japanese Americans during the 1940s: SECURITY OF WHOM?". Canadian Issues: 28–30.

- ↑ Roy (1990), p. 3

- ↑ Young (1938), p. xxii

- ↑ La Violette (1948), p. 17

- ↑ La Violette (1948), p. 8

- ↑ La Violette (1948), p. 18

- 1 2 Young (1938), pp. 8–9

- ↑ Gilmore, Julie. Trouble on Main Street: Mackenzie King, Reason, Race and the 1907 Riots.Toronto: Allan Lane, 2014, pp. 18.

- ↑ Roy (1990), p. 9

- 1 2 3 4 5 Izumi, Masumi. "Japanese Canadian exclusion and incarceration". Densho Encyclopedia. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- 1 2 Young (1938), p. 13

- ↑ Young (1938), p. 124

- ↑ Shibata (1977), pp. 9–10

- ↑ Shibata (1977), pp. 16–17

- ↑ Young (1938), p. 123

- ↑ Summary of Memorandum, Maj. Gen. Maurice Pope, Vice Chief of General Staff (VCGS) to Chief of General Staff (Permanent), 13 January 1942, extracted from HQS 7368, vol. I, Defence Records, 322.009(D358), DND. in The Politics of Racism by Ann Gomer Sunahara

- ↑ Young (1938), p. 175

- ↑ Young (1938), pp. 188–189

- ↑ La Violette (1948), p. 24–25

- ↑ Fujiwara, Aya. "Japanese-Canadian Internally Displaced Persons:Labour Relations and Ethno-Religious Identity in Southern Alberta, 1942–1953. Page 65

- ↑ Sunahara (1981), 28.

- ↑ Sunahara (1981), 37.

- ↑ Sunahara (1981), 46.

- ↑ Sugiman, Pamela. "Life is Sweet: Vulnerability and Composure in the Wartime Narratives of Japanese Canadians". Journals of Canadian Studies. Winter 2009: 186–218, 262.

- ↑ Sunahara, Ann. "The Politics of Racism: The Uprooting of Japanese Canadians During the Second World War." Toronto: J, Larimer, 1981.Pg 47–48.

- 1 2 Kobayashi, Audrey. "The Japanese-Canadian redress settlement and its implications for ‘race relations’" Canadian Ethnic Studies. Vol. 24, Issue 1.

- ↑ Paolini, David. "Japanese Canadian Internment and Racism During World War II" The Canadian Studies Undergraduate. 23 March 2010.

- ↑ Sunahara (1981), chapter 2.

- ↑ Sunahara (1981), chapter 3.

- ↑ Library and Archives Canada (LAC), RG25, vol. 3037, file 4166-40, letter from Captain V.C. Best to Hugh Keenleyside, 9 January 1941.

- ↑ LAC, RG25, vol. 3037, file 4166-40, letter from Captain V.C. Best to Hugh Keenleyside, 2 February 1941. LAC, RG25, vol. 3037, file 4166-40, letter from Captain V.C. Best to Hugh Keenleyside, 13 January 1942. LAC, RG25, vol. 3037, file 4166-40, letter from Captain V.C. Best to Hugh Keenleyside, 7 February 1943.

- ↑ World Leaders of the Twentieth Century. Pasedena, CA: Salem Press. 2000. p. 425.

- ↑ Dreisziger, N F. "7 December 1941: A turning point in Canadian wartime policy toward enemy ethnic groups?" Journal of Canadian Studies. Spring 1997: 93–11

- ↑ Johnson, Gregory A. "An Apocalyptic Moment: Mackenzie King and the Bomb". Pg 103

- ↑ King Diary, 6 August 1945.

- ↑ Walker, James W. St. G. (Mar 1989). "Race and Recruitment in World War I: Enlistment of Visible Minorities in the Canadian Expeditionary Force". Canadian Historical Review. 70 (1): 3, 6. doi:10.3138/chr-070-01-01.

- ↑ Walker (1989), 7.

- ↑ Dick, Lyle (2010). "Sergeant Masumi Mitsui and the Japanese Canadian War Memorial" (PDF). Canadian Historical Review. 3. 91: 442–43. doi:10.1353/can.2010.0013.

- ↑ Walker (1989), 12.

- 1 2 Neary, Peter (2004). "Zennousuke Inouye's Land: A Canadian Veterans Affairs Dilemma". Canadian Historical Review. 85 (3): 423–450. doi:10.1353/can.2004.0123.

- 1 2 "Will Register B.C Japanese to Eliminate Illegal Entrants," Globe and Mail (Toronto: January 9, 1941)

- ↑ "National Association of Japanese Canadians". Najc.ca. Archived from the original on 2011-08-26. Retrieved 2014-02-06.

- ↑ Omatsu (1992), p. 77-78

- ↑ Omatsu (1992), p. 12

- ↑ Wild Daisies in the Sand: Life in a Canadian Internment Camp, Tsuneharu Gonnami, Pacific Affairs, Winter 2003/2004.

- 1 2 My Sixty Years in Canada, Dr. Masajiro Miyazaki, self-publ.

- ↑ "Propose Japs Work in Orchards of B.C," Globe and Mail (Toronto: January 16, 1942)

- ↑ Carmela Patrias, "Race, Employment Discrimination, and State Complicity in Wartime Canada, 1939–1945," Labour no. 59 (April 1, 2007), 32.

- ↑ Sunahara (1981), 66.

- ↑ Sunahara (1981), 68.

- ↑ Sunahara (1981), 74–75.

- ↑ Explanation of different categories of internment, Nat'l Assn. of Japanese Canadians website Archived 2006-06-22 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Map of Internment Centres in BC, Nat'l Assn. of Japanese Canadians website Archived 2007-03-25 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Sunahara (1981), 55, 78.

- ↑ Oikawa, Mona. Cartographies of Violence: Japanese Canadian Women, Memory, and the Subjects of the Internment. Toronto: U of Toronto, 2012. Print.

- ↑ Henderson, Jennifer, and Pauline Wakeham. Reconciling Canada: Critical Perspectives on the Culture of Redress. Toronto: U of Toronto, 2013. Print

- ↑ James (2008), p. 22

- ↑ Omatsu (1992), pp. 73–74

- ↑ Japanese Canadian Internment Archived 2007-06-13 at the Wayback Machine., University of Washington Libraries

- ↑ Nakano (1980), p. 41

- ↑ Nakano (1980), p. 45

- ↑ The Dewdney Trail, 1987, Heritage House Publishing Company Ltd.

- 1 2 3 Sunahara (1981), chapter 4.

- ↑ Hester, Jessica Leigh (9 December 2016). "The Town That Forgot About Its Japanese Internment Camp". CityLab. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Establishing Recognition of Past Injustices: Uses of Archival Records in Documenting the Experience of Japanese Canadians During the Second World War. Roberts-Moore, Judith. Archivaria: The Journal of the Association of Canadian Archivists, 53 (2002).

- 1 2 Sunahara (1981), 101.

- ↑ Omatsu (1992), p. 73

- ↑ Sunahara (1981), 102.

- 1 2 3 Sunahara (1981), 103.

- ↑ Forrest E. LaViolette, "Japanese Evacuation in Canada," Far Eastern Survey, Vol. 11, No. 15 (Institute of Pacific Relations, 1942),165.

- ↑ "Jap Expropriation Hearing May Last 3 Years, Is Estimate," Globe and Mail (Toronto: January 12, 1948)

- 1 2 "Retreat Under Pressure," Globe and Mail (Toronto: January 27, 1947)

- ↑ Merciful Injustice, Facebook page of Merciful Injustice documentary

- ↑ Vancouver Sun series Merciful Injustice

- ↑ Adachi (1976), 320.

- ↑ Sunahara (1981), 104.

- ↑ Sunahara (1981), 105.

- ↑ Stanger-Ross, Jordan. "Suspect Properties: The Vancouver Origins of the Forced Sale of Japanese-Canadian-Owned Property, WWII". Journal of Planning History. 2016: 1–3.

- ↑ Roy, Patricia. The Triumph of Citizenship: The Japanese and Chinese in Canada, 1941–67. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2007, 116.

- ↑ Sunahara (1981), 105–106.

- ↑ Sunahara (1981), 107.

- 1 2 Adachi (1976), 322.

- 1 2 Sunahara (1981), 110.

- ↑ Sunahara (1981), 111.

- ↑ Adachi (1976), 325.

- ↑ Adachi (1976), 325–326.

- ↑ Adachi (1976), 327.

- ↑ Adachi (1976), 329–331.

- ↑ Adachi (1976), 321.

- ↑ Adachi (1976), 332.

- ↑ Japanese Internment – CBC

- ↑ Uprooted Citizens Living New Lives, Seem Contented in Toronto Area," Globe and Mail (Toronto: September 20, 1947)

- 1 2 Carmela Patrias, "Race, Employment Discrimination, and State Complicity in Wartime Canada," 36.

- ↑ Omatsu (1992), pp. 82, 83

- ↑ James (2008), p. 23

- ↑ James (2008), p. 24

- 1 2 Vineberg (2011), p. 199

- ↑ Toronto Star, Sept. 24, 1988

- 1 2 Apology and compensation, CBC Archives

- 1 2 Wood, Alexandra L. (2014). "Rebuild Or Reconcile: American and Canadian Approaches to Redress for World War II Confinement". American Review of Canadian Studies. 44.3: 352 – via Scholars Portal Journals.

- 1 2 3 Wood, Alexandra L. (2012). "Challenging History: Public Education and Reluctance to Remember the Japanese Canadian Experience in British Columbia". Historical Studies in Education. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ↑ Davis, Laura K. (2012). "Joy Kogawa's Obasan: Canadian Multiculturalism and Japanese-Canadian Internment". British Journal of Canadian Studies. 25.1: 57–76 – via ProQuest.

- ↑ Gagnon, Monika K. (2006). "Tender Research: Field Notes from the Nikkei Internment Memorial Centre, New Denver, BC". Canadian Journal of Communication. 31.1: 215–225 – via ProQuest.

Bibliography

- James, Kevin (2008). Seeking specificity in the universal: a memorial for the Japanese Canadians interned during the Second World War. Dalhousie University.

- La Violette, Forrest E. (1948). The Canadian Japanese and World War II: a Sociological and Psychological Account. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: University of Toronto Press.

- Nakano, Takeo Ujo (1980). Within the Barbed Wire Fence: a Japanese Man's Account of his Internment in Canada. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-2382-7.

- Omatsu, Maryka (1992). Bittersweet Passage: Redress and the Japanese Canadian Experience. Toronto: Between the Lines.

- Roy, Patricia E. (1990). Mutual Hostages: Canadians and Japanese during the Second World War. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-5774-8.

- Roy, Patricia E. (2002). "Lessons in citizenship, 1945–1949: the delayed return of the Japanese to Canada's Pacific coast". Pacific Northwest Quarterly. 93 (2): 69–80. JSTOR 40492798.

- Shibata, Yuko (1977). The Forgotten History of the Japanese Canadians: Volume I. Vancouver, BC: New Sun Books.

- Sugiman, Pamela (2004). "Memories of internment: narrating Japanese Canadian women's life stories". The Canadian Journal of Sociology. 29 (3): 359–388. doi:10.1353/cjs.2004.0049. JSTOR 3654672.

- Vineberg, Robert (2011). "Continuity in Canadian immigration policy 1947 to present: taking a fresh look at Mackenzie King's 1947 immigration policy statement". Journal of International Migration and Intergation. 12 (2): 199–216. doi:10.1007/s12134-011-0177-5.

- Young, Charles H. (1938). The Japanese Canadians. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: The University of Toronto Press.

Further reading

- Adachi, Ken. The Enemy that Never Was: A History of the Japanese Canadians (1976)

- Bangarth, Stephanie. "The long, wet summer of 1942: the Ontario Farm Service Force, small-town Ontario and the Nisei." Canadian Ethnic Studies Journal, Vol. 37, No. 1, 2005, p. 40-62. Academic OneFile, http://link.galegroup.com.proxy1.lib.uwo.ca/apps/doc/A137919909/AONE?u=lond95336&sid=AONE&xid=7bc85c86. Accessed 30 May 2018.

- Bangarth, Stephanie. Voices Raised in Protest: Defending North American Citizens of Japanese Ancestry, 1942–49 (UBC Press, 2008)

- Caccia, Ivana. Managing the Canadian Mosaic in Wartime: Shaping Citizenship Policy, 1939–1945 (McGill-Queen's University Press, 2010)

- Daniels, Roger. "The Decisions to Relocate the North American Japanese: Another Look," Pacific Historical Review, Feb 1982, Vol. 51 Issue 1, pp 71–77 argues the U.S. and Canada coordinated their policies

- Day, Iyko. "Alien Intimacies: The Coloniality of Japanese Internment in Australia, Canada, and the U.S." Amerasia Journal, 2010, Vol. 36 Issue 2, pp 107–124

- Dhamoon, Rita, and Yasmeen Abu-Laban. "Dangerous (Internal) Foreigners and Nation-Building: The Case of Canada." International Political Science Review / Revue Internationale De Science Politique, vol. 30, no. 2, 2009, pp. 163–183. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25652897.

- Dowe, David. "The Protestant Churches and the Resettlement of Japanese Canadians in Urban Ontario, 1942–1955," Canadian Ethnic Studies, 2007, Vol. 39 Issue 1/2, pp 51–77

- Kogawa, Joy. "Obasan" (Lester & Orpen Dennys, 1981)

- Roy, Patricia E. The Triumph of Citizenship: The Japanese and Chinese in Canada 1941–1967 (2007)

- Sugiman, Pamela. "'Life is Sweet': Vulnerability and Composure in the Wartime Narratives of Japanese Canadians," Journal of Canadian Studies, Winter 2009, Vol. 43 Issue 1, pp 186–218

- Sunahara, Ann Gomer. The politics of racism: The uprooting of Japanese Canadians during the Second World War (James Lorimer & Co, 1981)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Internment of Japanese-Canadians. |

- The New Canadian, a newspaper published by interned Japanese Canadians

- CBC Archives – Relocation to Redress: The Internment of the Japanese Canadians

- Co-operative Committee on Japanese Canadians v. Attorney-General for Canada, [1947] A.C. 87 – Privy Council decision, 2 Dec. 1946

- "Kimiko Murakami: A Picture of Strength" by John Endo Greenaway

- "The Politics of Racism" by Ann Gomer Sunahara 1981 book in PDF and HTML formats.

- Canada's Human Rights History

- TASHME: Life in a Japanese Canadian Internment Camp, 1942–1946

- Records of Japanese Canadian Blue River Road Camp Collection are held by Simon Fraser University's Special Collections and Rare Books