Chinatown, Vancouver

| Chinatown, Vancouver | |||||||||||||||

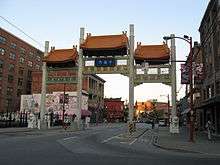

Millennium Gate on Pender Street in Chinatown | |||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 溫哥華唐人街 | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 温哥华唐人街 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 溫哥華華埠 | ||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 温哥华华埠 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Designations | |

|---|---|

| Official name | Vancouver's Chinatown National Historic Site of Canada |

| Designated | 2011 |

Chinatown in Vancouver, British Columbia, is Canada's largest Chinatown. Centred on Pender Street, it is surrounded by Gastown and the Downtown financial and central business districts to the west, the Downtown Eastside to the north, the remnant of old Japantown to the northeast, and the residential neighbourhood of Strathcona to the east. The approximate borders of Chinatown as designated by the City of Vancouver are the alley between Pender and Hastings Streets, Georgia Street, Gore Avenue, and Taylor Street,[1] although unofficially the area extends well into the rest of the Downtown Eastside. Main, Pender, and Keefer Streets are the principal areas of commercial activity.

Chinatown remains a popular tourist attraction and is one of the largest historic Chinatowns in North America. However, it experienced decline as newer members of Vancouver's Cantonese Chinese community dispersed to other parts of the metropolitan area. It has been more recently overshadowed by the newer Chinese immigrant business district along No. 3 Road in the City of Richmond, south of Vancouver. Many affluent Hong Kong and Taiwanese immigrants have moved there since the late 1980s, coinciding with the increase of Chinese ethnic retail and restaurants in that area. This new area is designated the "Golden Village" by the City of Richmond. The proposed renaming of the area to "Chinatown" met resistance both from merchants in Vancouver's Chinatown and from non-Chinese residents and merchants in Richmond itself.

Chinatown was once known for its neon signs, but like the rest of the city, lost many signs to changing times and a sign bylaw passed in 1974. The last of these was the Ho Ho sign (which showed a rice bowl and chop sticks), which was removed in 1997. Ongoing efforts at revitalization include efforts by the business community to improve safety by hiring private security, considering new marketing promotions, and introducing residential units into the neighbourhood by restoring and renovating heritage buildings. The current focus is on the restoration and adaptive reuse of the distinctive association buildings.

Due to the large ethnic Chinese presence in Vancouver—especially represented by multi-generation Chinese Canadians and first-generation immigrants from Hong Kong—the city has been referred to as "Hongcouver".[2]

Amenities

Chinatown is becoming more prosperous as new investment and old traditional businesses flourish. Today the neighbourhood features many traditional restaurants, banks, markets, clinics, tea shops, clothing stores, and other shops catering to the local community and tourists alike. The Vancouver office of Sing Tao Daily, one of the city's four Chinese-language dailies, remains in Chinatown. OMNI British Columbia (formerly Channel M) had its television studio in Chinatown from 2003 to 2010.

Recent developments

Vancouver experienced large numbers of immigrants from the Asia-Pacific region in the last two decades of the twentieth century, most notably from China, whose population in the Vancouver Census Metropolitan Area was estimated at 300,000 in the mid-1990s.[3] A significant development since the 1980s has been the increase of transnational awareness among the Chinese. The heightened mobility of capital, information, people, and commodities across territorial boundaries and distance challenged the traditional meaning of migration. Compared to Chinatown itself, more Chinese immigrants have settled in Richmond, drawn by its lower house prices, considerable concentration of Chinese retailers, and the nearby Vancouver airport. The business heart of Chinatown was visibly affected after the arrival of suburban Asian shopping districts, such as Richmond's Aberdeen Centre, which was promoted as North America's largest enclosed Asian mall in the proximity of other Chinese shopping centres, and which offered more parking and open space than historic Chinatown.

In 1979, the Chinatown Historic Area Planning Committee sponsored a streetscape improvement program to add various Chinese-style elements to the area, such as specially paved sidewalks and red dragon streetlamps that demarcated the area's borders while emphasizing it as a destination for heritage tourism. Starting with its designation by the province as a historic area in 1971 and subsequent economic shifts,[4] Chinatown shifted from a central business district to playing a largely cultural role. Murality, a local non-profit, is installing a mural on East Pender Street with the aim of bringing colour and vitality to the neighbourhood.

The growth of Chinatown during much of the 20th century created a healthy, robust community that gradually became an aging one as many Chinese immigrants no longer lived nearby. Noticing local businesses suffering, the Chinatown Merchants Association cited the lack of parking and restrictive heritage district rules as impediments to new uses and renovations. Their concerns subsequently led to a relaxation of zoning laws to allow for a wider range of uses, including necessary demolition.[5] Additions in the mid-1990s included a large parkade, a shopping mall, and the largest Chinese restaurant in Canada. More residential projects around the community and a lowering of property taxes helped to maintain a more rounded community. Reinvigoration was a discussed topic along government members, symbolically embedded in the Millennium Gate project, which opened in 2002.[6] It can be argued that the role of the early Chinese settlers in Vancouver's Chinatown area in the late 19th and early 20th centuries helped to put Vancouver on the global map as a popular destination for Asian investment and immigration.

New business strategies

Chinatown's businesses today predominantly consist of those selling lower-order, working-class goods, such as groceries, tea shops, and souvenir stores. While some businesses, such as restaurants, stand out, they are no longer the only Chinese food establishments in the city, a shift that contributed to a visible decline in foot traffic and nighttime activity in Chinatown. As the vacancy rate in Chinatown currently stands at 10%, it has been acknowledged that Chinatown needs a new approach to development, since some businesses have relocated to suburban shopping centres while others simply retired or went out of business. Examples include the closing of some restaurants and shops, sometimes in instances where the family did not have successors or where the business could not sustain itself any longer. Although there is a considerable business vacancy, Chinatown lease rates are considered the cheapest in the city, at $15–$30 per square foot—about one-tenth of the asking price on Vancouver's Downtown Robson Street, the city's upscale shopping district.

The new Chinatown business plan encourages new entrepreneurs to move in—and has attracted a longboard store and German sausage shop—as ways of restoring storefronts and bringing in a younger crowd, and to make higher-income people more comfortable in the area.[7] Attracted to the lower rent and the building's heritage status, younger businesses have moved in, often with white owners who also live in apartments above the shops.[8] The general consensus is that Chinatown's priority is to attract people of all backgrounds to Chinatown, and it is believed that the opening of non-traditional stores will bring a new flow of energy and income to the streets.[9] As a result, the commercial activity is becoming more diversified, dotted with Western chain stores such as Waves Coffeeshop and Dollar Giant. Other additions include vintage stores, two art galleries, bars, and a nightclub, built on the site of the former Ming's restaurant,[10] in an attempt to bring something of a nightlife atmosphere, reminiscent of the 1950s and 1960s, back to the neighbourhood. The diversity of new shops and businesses is believed to be necessary in creating a new image for Chinatown in order to bring vibrancy back to the area and encourage commercial activities in general, and as a way to compete with suburban districts as well as nearby Gastown and Downtown Vancouver.

Chinatown Revitalization Action Plan

The Chinatown Historic Area planning committee, along with AECOM Economics, a US-based planning firm, helped to prepare a Chinatown Revitalization Action Plan for Vancouver's planning department in November 2011.[11] Vancouver planners surveyed 77 businesses and found that 64% reported a decrease in revenue between 2008 and 2011. The majority of consumers, 58%, were local residents, with 21% coming from elsewhere in the Lower Mainland. Tourist spending accounted for only 12% of Chinatown customers.[12] Recognizing the shifting role of Chinatown, the report highlighted key points to help the district keep up with the times:

- Although Chinatown experienced rapid residential growth, Vancouver's Chinese population is no longer concentrated in the Chinatown area, as new immigration settlement is dispersed throughout Metro Vancouver, especially in Richmond.

- Historically, Chinese immigrants to Vancouver were predominantly from Southern China, while immigrants today come from throughout China and Asia. Therefore, Chinatown restaurants need to broaden their offerings beyond mostly Cantonese dishes to cuisine from other parts of China and Asia in order to serve a more diversified consumer base.

Building on these points, the report recommended that Chinatown needs:

- More life on the streets at night and on weekends as a way to dilute social problems

- To provide better restaurants, as these make up the heart of Chinatown and are key to improving its business sector

- To modernize the cultural centre and museum as a viable attraction while keeping its neighbourhood aspects

- To cater more to its residents through everyday services such as groceries and restaurants

- To take advantage of its fine-grained streetscape pattern, which offers a unique sidewalk experience compared to newer auto-oriented suburban areas

- To involve younger community members in decision-making roles

- To renovate its 20 heritage buildings, creating a historic district unparalleled in Western Canada, which will increase appeal to tourists and residents, leading to more local spending

- To be clean and safe in order to reduce negative images, such as illegal drug use and panhandling, associated with the Downtown Eastside in general

Condominium Development

Vancouver city councillors voted in 2011 to raise building height restrictions in Chinatown in order to boost its population density. A limit of 9 stories for most of the neighbourhood was set, with a maximum of 15 stories on the busiest streets.[13] Highrises close to Stadium-Chinatown Station have already been built, with more condominium towers under construction, some projects taking advantage of empty lots that sat unused for decades. Due to the unconventional lot sizes, one 9-storey condominium is only 25 feet wide. However, that is not expected to be a problem in Vancouver, which has a market for affordable smaller-scale homes. Critics of highrise development speculate that the plan will effectively divide up the neighbourhood to form a "Great Wall of Chinatown" as lower-income residents are marginalized and displaced.

Facts and figures

- The China Gate on Pender Street was donated to the City of Vancouver by the Government of the People's Republic of China following the Expo 86 world's fair, where it was on display. After being displayed for almost 20 years at its current location, the gate was rebuilt and received a major renovation of it façade employing stone and steel. Funding for the renovation came from government and private sources; the renovated gate was unveiled during the October 2005 visit of Guangdong governor Huang Huahua.

- The Sam Kee Building: The Sam Kee Company, run by Chang Toy, one of the wealthier merchants in turn-of-the-20th-century Chinatown, bought this land as a standard-sized lot in 1903. However, in 1912 the city widened Pender Street, expropriating all but 6 feet of the Pender Street side of the lot. In 1913 the architects Brown and Gillam designed this narrow, steel-framed free-standing building on the remaining 6-foot strip. The basement, extending under the sidewalk and much wider than the rest of the building, housed public baths, with shops on the ground floor and offices above (such basements in Vancouver were once common and zoned as "areaways"). The 1980s' rehabilitation of the building for Jack Chow was designed by Soren Rasmussen Architect and completed in 1986. The building is the narrowest commercial building in the world, according to the Guinness Book of Records.

- Lord Strathcona Elementary School, the oldest public school in Greater Vancouver, is the only public school serving Vancouver's Chinatown.

- Wing Sang Building is one of the oldest buildings in Chinatown. Built in 1889 by Thomas Ennor Julian, the 6-storey home was home to Yip Sang's Wing Sang Company (Wing Sang Limited) from 1889 to 1955.

- In addition to Han Chinese from Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Mainland China, Chinese Latin Americans have also settled in the Chinatown area. Most of them were from Peru and arrived shortly after Juan Velasco Alvarado took over that country in a military coup in 1968. Others have come from Brazil, Mexico, and Nicaragua.

- The neighbourhood was designated a National Historic Site of Canada in 2011.[14]

List of historic buildings in Chinatown

| Name | Location | Builder/Designer | Year | Built by/for | Photo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sam Kee Building | 8 West Pender Street | Brown and Gillam | 1913 | Sam Kee Company | |

| Wing Sang Building | 51 East Pender Street | Thomas Ennor Julian | 1889–1901 | Wing Sang Company | |

| Chinese Freemasons Building | 1 West Pender Street | 1901 | |||

| Chinese Benevolent Association of Vancouver | 104–108 E Pender Street | 1901–10 | Chinese Benevolent Association | ||

| Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden | 578 Carrall St | Joe Wai, Donald Vaughan, Wang Zu-Xin | 1986 | [15] | |

| Lim Sai Hor Association Building | 525–531 Carrall Street | Samuel Buttrey Birds, W. H. Chow[16] | 1903 | Chinese Empire Reform Association | |

| Mah Society of Canada | 137–139 E Pender Street | 1913 | |||

| Shon Yee Benevolent Association | 258 E Pender Street | 1914 | |||

| Yue Shan Society | 33–47 E Pender St. | W.H. Chow | 1898, 1920 | ||

| Chinese Times Building | 1 East Pender Street | William Tuff Whiteway | 1902 | Wing Sang Company | |

| Mon Keang School | 123 East Pender Street | J.A. Radford and G.L. Southall | 1921 | Mon Keang School | |

| Lee Building | 129–131 East Pender Street | Henriquez and Todd | 1907 | Lee's Association | |

| Carnegie Community Centre | 401 Main Street | G.W. Grant | 1902–03 | Vancouver Public Library; later as Vancouver Museum and City Archives | |

| Commercial Buildings | 237–257 East Hastings Street | 1901–13 | |||

| Hotel East | 445 Gore Street | S.B. Birds | 1912 | ||

| Kuomintang Building | 296 East Pender Street | W.E. Sproat | 1920 | The Kuomintang (KMT, or Chinese Nationalist League) | |

| Chin Wing Chun Society | 160 East Pender Street | R.A. McKenzie | 1925 | ||

| Ho Ho Restaurant and Sun Ah Hotel | 102 East Pender Street | R.T. Perry and White and Cockrill | 1911 | Loo Gee Wing | |

| May Wah Hotel | 258 East Pender Street | William Frederick Gardiner Architect for Messrs. Barrett and Deane | 1913 | Shon Yee Benevolent Association of Canada | [17] |

| Chau Luen Tower | 325 Keefer | 1971 | Chau Luen Benevolent Society | ||

| London Drugs | 800 Main St | Unknown-1968 (Expropriated) | Chau Luen Benevolent Society | [18] |

International Village

In recent years Chinatown has seen growth in new construction as a downtown building boom continued into the former Expo 86 lands, which adjoin Chinatown. New high-rise towers are being constructed around the old Expo 86 site, including International Village, which was built in 1998 and is located next to Stadium–Chinatown SkyTrain station. Anchored by Cineplex Odeon International Village Cinemas and flanked by Rexall Drugstore and Yokoyaya 123, the International Village Shopping Centre is a 300,000 ft² entertainment and shopping venue. It is one of the first master-planned communities in Greater Vancouver; is the central hub connecting Gastown, Chinatown, and Yaletown; and is adjacent to the Rogers Arena, the Plaza of Nations, and BC Place Stadium.

International Village was designed to be downtown's answer to the Asian malls found in the Golden Village, though it is not as racially exclusive and includes businesses and residents that are non-Chinese.

International Village also refers to the name given to the area by developer Henderson Development (Canada) Ltd., a subsidiary of Henderson Land Development.

International Village was commonly called Tinseltown, based on one of the brands of theatre chain Cinemark Theatres, which owned the building before Cineplex did.

Clan societies

Chinese immigrants, primarily men, first came to Vancouver in the late 19th century. As more people of Chinese heritage came to Vancouver, clan associations were formed to help the newcomers assimilate in their adopted homeland and to provide friendship and support. Clan societies were often formed around a shared surname lineage, county (e.g., Kaiping, Zhongshan), or other feature of identity.[19]

Notable residents

- Wong Foon Sien, journalist and social activist

- Bessie Lee, community organizer and civic activist

- Mary Lee Chan, civic activist

- Shirley Chan, civic activist

- Yip Sang, businessman

- Yucho Chow, photographer

- Wayson Choy, author, educator

Community Groups

- Chinatown Today, newspaper

- Hua Foundation, non-profit

See also

- Chinese Canadians in British Columbia

- Everything Will Be, Julia Kwan's 2014 documentary film about Chinatown

References

- ↑ Map of official boundaries of Chinatown, City of Vancouver website

- ↑ Chinese Vancouver: A decade of change Archived 2007-10-30 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Ng, Wing Chung (1999). The Chinese in Vancouver 1945-80. Vancouver: UBC Press. p. 137. ISBN 0-7748-0733-4.

- ↑ Davis, Chuck (2011). The Chuck Davis History of Metropolitan Vancouver. Harbour Publishing. p. 351. ISBN 978-1-55017-533-2.

- ↑ Yee, Paul (2006). Saltwater City. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre Ltd. p. 219. ISBN 978-1-55365-174-1.

- ↑ "Millennium Gate". Archived from the original on 8 October 2012. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ "Behind the Changing Face of Vancouver's Chinatown". Toronto: Globe and Mail. 13 January 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ Quinn, Stephen (8 February 2013). "Saving Chinatown, One Sausage and Pilates pose at a Time". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ Allingham, Jeremy. "Vancouver's Chinatown embraces change". CBC News. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ "Fortune Sound Club". Archived from the original on 19 February 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ "Chinatown Revitalization". Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ Howell, Mike. "Vancouver prepares plan to renew ailing Chinatown". Vancouver Courier. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ Hutchinson, Brian (Sep 28, 2012). "Can condo-zones save Vancouver's beleaguered Chinatown?". National Post. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ Vancouver's Chinatown. Directory of Federal Heritage Designations. Parks Canada. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ↑ "Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden". Wikipedia. 2018-02-26.

- ↑ "HistoricPlaces.ca - HistoricPlaces.ca". www.historicplaces.ca. Retrieved 2018-03-17.

- ↑ "HistoricPlaces.ca - HistoricPlaces.ca". www.historicplaces.ca. Retrieved 2018-03-17.

- ↑ "Chinatown and Hogan's Alley advocates call for greater reconciliation in Vancouver's Northeast False Creek Plan | Metro Vancouver". metronews.ca. Retrieved 2018-03-17.

- ↑ Contractor to City of Vancouver (2005). HISTORIC STUDY OF THE SOCIETY BUILDINGS IN CHINATOWN. http://vancouver.ca/files/cov/historic-study-of-the-society-buildings-in-chinatown.pdf: City of Vancouver. p. 1.

Further reading

- Anderson, Kay. Vancouver's Chinatown: Racial Discourse in Canada, 1875–1980 (Montreal and Buffalo: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1991).

- Anderson, Kay. Cultural Hegemony and the Race Definition Process in Vancouver's Chinatown: 1880–1980 in Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 1988. Reprinted in 1996, Social Geography: A Reader, ed. Hamnett C., (Arnold, London)

- Anderson, Kay. The idea of Chinatown: the Power of Place and Institutional Practice in the Making of a Racial Category in Annals Association of American Geographers (1987 - vol. 77, no. 4). Reprinted in 1992, A Daunting Modernity: A Reader in Post-Confederation Canada ed. McKay, I (McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ontario).

- Ng, Wing Chung. ' 'The Chinese in Vancouver 1945–80: The Pursuit of Identity and Power' ' (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1999).

- Yee, Paul. Saltwater City: An Illustrated History of the Chinese in Vancouver (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2006).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chinatown, Vancouver. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Gastown-Chinatown. |

- Vancouver Chinatown Revitalization Committee website

- "For the love of Chinatown," 1968 clip from CBC Radio

- Chinese Community Policing Centre

- Vincent Miller, "Mobile Chinatowns: The Future of Community in a Global Space of Flows." Article analyzing the differences between Vancouver's Chinatown and the Chinese community in Richmond.

- "Yin and Yang: Chinatown Past and Present," Multimedia site from Knowledge Network based on Paul Yee's book, Saltwater City: An Illustrated History of the Chinese in Vancouver,Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 1988.

- Walking Tour: Chinatown

- "Chinatown Revitalization Project on the City of Vancouver Planning Department"

- "Chinatown Canada: The first in a four-part video series about Canada's Chinatowns from CityTv"

- Vancouver Chinatown - Simon Fraser University

Coordinates: 49°16′48″N 123°5′58″W / 49.28000°N 123.09944°W