Isfiya

Isfiya

| |

|---|---|

| Hebrew transcription(s) | |

| • ISO 259 | ʕisp̄íyaˀ |

View of the village | |

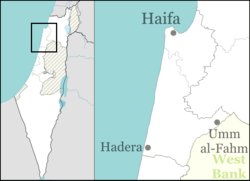

Isfiya Location within Israel | |

| Coordinates: 32°43′10″N 35°03′48″E / 32.71944°N 35.06333°ECoordinates: 32°43′10″N 35°03′48″E / 32.71944°N 35.06333°E | |

| Grid position | 156/236 PAL |

| District |

|

| Government | |

| • Type | Local council |

| Area | |

| • Total | 15,561 dunams (15.561 km2 or 6.008 sq mi) |

| Population (2017)[1] | |

| • Total | 12,136 |

| • Density | 780/km2 (2,000/sq mi) |

| Name meaning | The devious (road)[2] |

Isfiya (Arabic: عسفيا, Hebrew: עִסְפִיָא), also known as Ussefiya or Usifiyeh, is a Druze village and local council in northern Israel. Located on Mount Carmel, it is part of Haifa District. In 2017 its population was 10,543.[3] In 2003, the local council was merged with nearby Daliyat al-Karmel to form Carmel City. However, the new city was dissolved in 2008 and the two villages resumed their independent status.

History

Isfiya was built on the ruins of a Byzantine settlement. Crusader remnants have been found in the village. In 1930, remains of a 5th-century Jewish town, Husifah, were unearthed in Isfiya.[4] Among the finds are a synagogue with a mosaic floor bearing Jewish symbols and the inscription "Peace upon Israel." A cache of 4,500 gold coins were found dating from the Roman period.[5] A building, dating from the second–fourth centuries CE have been excavated, together with ceramics and coins dating from the period.[6]

Isfiya was mentioned as part of the domain of the Sultan during the hudna between the Crusaders based in Acre and the Mamluk sultan al-Mansur (Qalawun) declared in 1283.[7]

Ottoman era

The Druze came to the village in the early eighteenth century. The inhabitants made their living from olive oil, honey and grapes.[5]

Isfiya was one of only two villages remaining on Mount Carmel after the expulsion of Ibrahim Pasha in 1841. Seventeen other villages disappeared. The village's survival was attributed partly to "the exceptional valour" of the inhabitants, partly to buying protection from a local chief, Aqil Agha.[8]

In 1859, the English consul Rogers estimated the population to be 400, who cultivated 20 feddans of land.[9]

In the 1863, H.B. Tristram visited the village, which he described as Druze and Christian, with a Christian Sheikh.[10] Tristam noted that the women's clothing in this village were much like those of El Bussah, being either "plain, patched or embroidered in the most fantastic and grotesque shapes".[11]

In 1870, the French explorer Victor Guérin found that the village had six hundred inhabitants, almost all Druze, with the exception of sixty, who belonged to the "Schismatic Greeks". Gardens were grown all around the village. Some houses seemed very old and dated, Guérin surmised from the Middle Ages or even earlier, from the time of the Crusades.[12]

In 1881 the Palestine Exploration Fund's Survey of Western Palestine described it as standing "on the highest part of the Carmel watershed, and the highest house was therefore the trigonometrical station on the ridge. It is a moderate-sized village of stone houses, with a well on the south-west. The inhabitants are all Druses. [..] Corn-land and olives surround the land."[13]

A population list from about 1887 showed that Isfiya had about 555 inhabitants; 480 Druze and 75 Catholic Christians.[14]

British Mandate

In the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, 'Asfia had population of 733; 590 Druse, 17 Muslims and 126 Christians,[15] where the Christians were 6 Orthodox, 6 Roman Catholics, 107 Greek Catholics (Melchites), and 7 Maronites.[16] At the time of the 1931 census, Isfiya had 251 occupied houses and a population of 742 Druzes, 187 Christians, and 176 Muslims; a total of 1105. These counts included the smaller localities Damun Farm, Shallala Farm and El Jalama.[17]

In the 1945 statistics the population of Isfiya consisted of 1,790; 180 Muslims, 300 Christians and 1,310 classified as "others", that is, Druze,[18] while the land area was 46,905 dunams, according to an official land and population survey.[19] Of this, 1,103 dunams were designated for plantations and irrigable land, 17,357 for cereals,[20] while 74 dunams were built-up areas.[21]

During the 1936-39 Arab revolt in Palestine, the villagers initially supported a local rebel group led by Yusuf Abu Durra. However, after local leaders were abducted and murdered, the notables turned to the British, who destroyed the gang. A Druze self-defense force was established that received arms from the British and sometimes coordinated its activities with local Jewish forces.[22]

Post-1948

Though Isfiya is predominantly Druze, a number of Jews live there and in other Druze villages due to their low rent rates.[23]

Demographics

Isfiya consists of 10,543 citizens, 85% of which are Druze, 10% are Christian and about 5% are Muslim, and a few Jewish families .[24] The Christian population is mostly Roman Catholic, with a few Maronite households.

Landmarks

The tomb of Abu Abdallah is located in Isfiya. Abu Abdullah was one of three religious leaders chosen by Caliph Al-Hakem in 996 CE to proclaim the Druze faith. He is said to have been the first Druze religious judge (qadi). The Druze make an annual visit to this shrine on November 15.[25]

Mevo Carmel high-tech park

Isfiya and Daliyat al-Karmel joined Yokneam Illit and the Megiddo Regional Council to develop the Mevo Carmel Jewish-Arab Industrial Park[26] to benefit from the existing high-tech ecosystem.[27][28]

Notable residents

See also

References

- ↑ "List of localities, in Alphabetical order" (PDF). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

- ↑ Palmer, 1881, p. 109

- ↑ "The Central Bureau of Statistics - Populations in Israel by Town". www.cbs.gov.il. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- ↑ "Astrology and Judaism in Late Antiquity".

- 1 2 Druze Jewish Virtual Library

- ↑ Oren, 2008, ‘Isfiya

- ↑ Dan Barag (1979). "A new source concerning the ultimate borders of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem". Israel Exploration Journal. 29. pp. 197–217.

- ↑ Tristram, 1865, p. 112

- ↑ Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP I, p. 282

- ↑ Tristram, 1865, pp 111- 114

- ↑ Weir, 1989, p. 80, citing Tristram, 1865, p. 68

- ↑ Guérin, 1875, pp. 248-249

- ↑ Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP I, pp. 281 -282

- ↑ Schumacher, 1888, p. 178

- ↑ Barron, 1923, Table XI, Sub-District of Haifa, p. 33

- ↑ Barron, 1923, Table XVI, p. 49

- ↑ Mills, 1932, p. 92

- ↑ Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 14

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 48

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 90

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 140

- ↑ Archived July 11, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Jews Moving to Druze Villages". Arutz Sheva.

- ↑ "הרשות לפיתוח הגליל - בואו להכיר את עוספיא". www.galil.gov.il. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- ↑ The Abu Abdullah Shrine in Isfiya Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs

- ↑ "מבוא כרמל".

- ↑ "Mevo Carmel". The Center for Jewish - Arab Economic Development. Archived from the original on 1 August 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-10-06. Retrieved 2014-04-27.

Bibliography

- Barag, Dan (1979). "A new source concerning the ultimate borders of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem". Israel Exploration Journal. 29: 197–217.

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 1. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Guérin, V. (1875). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). 2: Samarie, pt. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Oren, Eliran (2008-12-04). "'Isfiya" (120). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Schumacher, G. (1888). "Population list of the Liwa of Akka". Quarterly statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. 20: 169–191.

- Tristram, H.B. (1865). Land of Israel, A Journal of travel in Palestine, undertaken with special reference to its physical character. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

- Weir, Shelagh (1989). Palestinian Costume. British Museum Publications Ltd. ISBN 0-7141-2517-2.

External links

- Welcome To 'Isfiya

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 5: IAA, Wikimedia commons