Interpol

| International Criminal Police Organization | |

|---|---|

| |

| Common name | Interpol |

| Abbreviation | ICPO-INTERPOL |

| Motto | “Connecting police for a safer world” |

| Agency overview | |

| Formed | 1923 |

| Employees | 756 (2013)[1] |

| Annual budget |

€78 million (2013) €113 million (2017) |

| Jurisdictional structure | |

| International agency | |

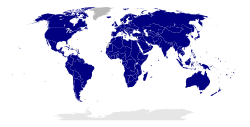

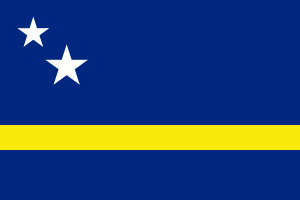

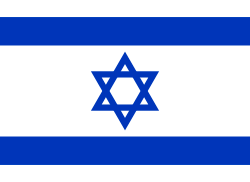

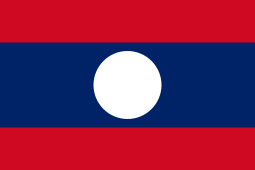

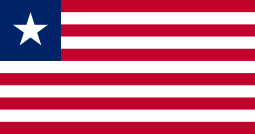

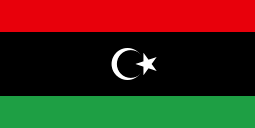

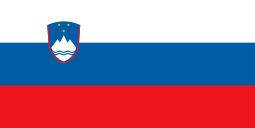

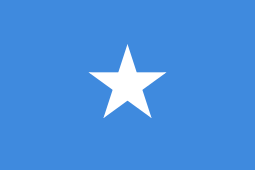

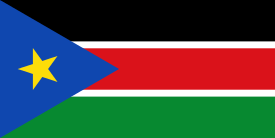

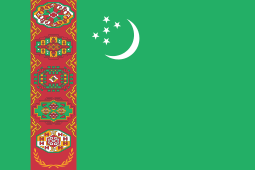

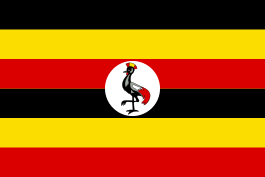

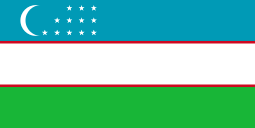

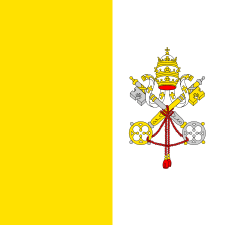

| Countries | 192 member countries |

| |

| Map of International Criminal Police Organization's jurisdiction. | |

| Governing body | INTERPOL General Assembly |

| Constituting instrument | |

| Headquarters | Lyon, France |

|

| |

| Agency executives |

|

| Facilities | |

| National Central Bureaus | 192 |

| Website | |

|

www | |

The International Criminal Police Organization (ICPO-INTERPOL; French: Organisation internationale de police criminelle), more commonly known as Interpol, is the international organization that facilitates international police cooperation. It was established as the International Criminal Police Commission (ICPC) in 1923; it chose INTERPOL as its telegraphic address in 1946, and made it its common name in 1956.[4]

INTERPOL has an annual budget of around €113 million, most of which is provided through annual contributions by its membership of police forces in 192 countries (as of 2017). In 2013, the INTERPOL General Secretariat employed a staff of 756, representing 100 member countries.[1] Its current Secretary-General is Jürgen Stock, the former deputy head of Germany's Federal Criminal Police Office. He replaced Ronald Noble, a former United States Under Secretary of the Treasury for Enforcement, who stepped down in November 2014 after serving 14 years.[5] Interpol's acting President is Kim Jong Yang of South Korea, replacing Meng Hongwei, Deputy Minister of Public Security of China, who resigned by mail in October 2018 after his detention by Chinese authorities on corruption charges.[6]

To keep INTERPOL as politically neutral as possible, its charter forbids it, at least in theory, from undertaking interventions or activities of a political, military, religious, or racial nature or involving itself in disputes over such matters.[7] Its work focuses primarily on public safety and battling transnational crimes against humanity, child pornography, cybercrime, drug trafficking, environmental crime, genocide, human trafficking, illicit drug production,[8] copyright infringement, missing people, illicit traffic in works of art, intellectual property crime, money laundering, organized crime, corruption, terrorism, war crimes, weapons smuggling, and white-collar crime.

History

In the first part of the 20th century, several efforts were taken to formalize international police cooperation, but they initially failed.[9] Among these efforts were the First International Criminal Police Congress in Monaco in 1914, and the International Police Conference in New York in 1922. The Monaco Congress failed because it was organized by legal experts and political officials, not by police professionals, while the New York Conference failed to attract international attention.

In 1923, a new initiative was taken at the International Criminal Police Congress in Vienna, where the International Criminal Police Commission (ICPC) was successfully founded as the direct forerunner of INTERPOL. Founding members included police officials from Austria, Germany, Belgium, Poland, China, Egypt, France, Greece, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Romania, Sweden, Switzerland, and Yugoslavia.[10] The United Kingdom joined in 1928.[11] The United States did not join Interpol until 1938, although a US police officer unofficially attended the 1923 congress.[12]

Following Anschluss in 1938, the organization fell under the control of Nazi Germany, and the Commission's headquarters were eventually moved to Berlin in 1942.[13] Most members withdrew their support during this period.[10] From 1938 to 1945, the presidents of the ICPC included Otto Steinhäusl, Reinhard Heydrich, Arthur Nebe, and Ernst Kaltenbrunner. All were generals in the SS, and Kaltenbrunner was the highest ranking SS officer executed after the Nuremberg Trials.

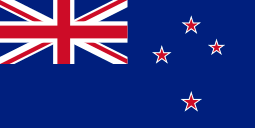

After the end of World War II in 1945, the organization was revived as the International Criminal Police Organization by officials from Belgium, France, Scandinavia and the United Kingdom. Its new headquarters were established in Saint-Cloud, a suburb of Paris. They remained there until 1989, when they were moved to their present location in Lyon.

Until the 1980s, INTERPOL did not intervene in the prosecution of Nazi war criminals in accordance with Article 3 of its Charter, which prohibited intervention in "political" matters.[14]

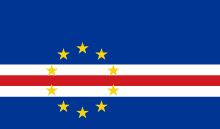

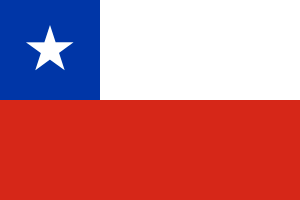

In July 2010, former INTERPOL President Jackie Selebi was found guilty of corruption by the South African High Court in Johannesburg for accepting bribes worth €156,000 from a drug trafficker.[15] After being charged in January 2008, Selebi resigned as president of INTERPOL and was put on extended leave as National Police Commissioner of South Africa.[16] He was temporarily replaced by Arturo Herrera Verdugo, the National Commissioner of Investigations Police of Chile and former vice president for the American Zone, who remained acting president until October 2008 and the appointment of Khoo Boon Hui.[17]

On 8 November 2012, the 81st General Assembly closed with the election of Deputy Central Director of the French Judicial Police Mireille Ballestrazzi as the first female president of the organization.[18][19]

In November 2016, Meng Hongwei, a politician from the People's Republic of China, was elected president during the 85th Interpol General Assembly, and was to serve in this capacity until 2020.[20] At the end of September 2018, Interpol President Meng Hongwei was reported missing during a trip to China, after being "taken away" for questioning by "discipline authorities". [21][22] On 7 October 2018, the organization announced that Meng had resigned his post with immediate effect and that the Presidency would be temporarily occupied by INTERPOL Senior Vice-President (Asia) Kim Jong Yang of South Korea.

Constitution

The role of INTERPOL is defined by the general provisions of its constitution.[2]

Article 2 states that its role is:

- To ensure and promote the widest possible mutual assistance between all criminal police authorities within the limits of the laws existing in the different countries and in the spirit of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

- To establish and develop all institutions likely to contribute effectively to the prevention and suppression of ordinary law crimes.

Article 3 states:

It is strictly forbidden for the Organization to undertake any intervention or activities of a political, military, religious or racial character.

Methodology

Contrary to frequent portrayals in popular culture, Interpol is not a supranational law enforcement agency and has no agents who are allowed to make arrests.[23] Instead, it is an international organization that functions as a network of criminal law enforcement agencies from different countries. The organization thus functions as an administrative liaison among the law enforcement agencies of the member countries, providing communications and database assistance, assisted via the central headquarters in Lyon, France.[24]

Interpol's collaborative form of cooperation is useful when fighting international crime because language, cultural and bureaucratic differences can make it difficult for police officials from different nations to work together. For example, if FBI special agents track a terrorist to Italy, they may not know whom to contact in the Polizia di Stato, if the Carabinieri have jurisdiction over some aspect of the case, or who in the Italian government must be notified of the FBI's involvement. The FBI can contact the Interpol National Central Bureau in Italy, which would act as a liaison between the United States and Italian law enforcement agencies.

Interpol's databases at the Lyon headquarters can assist law enforcement in fighting international crime.[23] While national agencies have their own extensive crime databases, the information rarely extends beyond one nation's borders. Interpol's databases can track criminals and crime trends around the world, specifically by means of authorized collections of fingerprints and face photos, lists of wanted persons, DNA samples, and travel documents. Interpol's lost and stolen travel document database alone contains more than 12 million records. Officials at the headquarters also analyze these data and release information on crime trends to the member countries.

An encrypted Internet-based worldwide communications network allows Interpol agents and member countries to contact each other at any time. Known as I-24/7, the network offers constant access to Interpol's databases.[23] While the National Central Bureaus are the primary access sites to the network, some member countries have expanded it to key areas such as airports and border access points. Member countries can also access each other's criminal databases via the I-24/7 system.

Interpol issued 13,637 notices in 2013, of which 8,857 were Red Notices, compared to 4,596 in 2008 and 2,037 in 2003. As of 2013, there are currently 52,880 valid notices in circulation.[1]

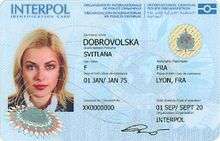

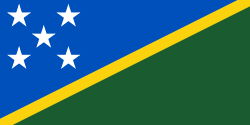

In the event of an international disaster, terrorist attack, or assassination, Interpol can send an Incident Response Team (IRT). IRTs can offer a range of expertise and database access to assist with victim identification, suspect identification, and the dissemination of information to other nations' law enforcement agencies. In addition, at the request of local authorities, they can act as a central command and logistics operation to coordinate other law enforcement agencies involved in a case. Such teams were deployed eight times in 2013.[1] Interpol began issuing its own travel documents in 2009 with hopes that nations would remove visa requirements for individuals traveling for Interpol business, thereby improving response times.[25] In September 2017, the organization voted to accept Palestine and the Solomon Islands as members.[26]

Finances

In 2013, Interpol's operating income was €78 million, of which 68 percent was contributed by member countries, mostly in the form of statutory contributions (67 percent) and 26 percent came from externally funded projects, private foundations and commercial enterprises. Financial income and reimbursements made up the other six percent of the total.[1] With the goal of enhancing the collaboration between Interpol and the private sector to support Interpol's missions, the Interpol Foundation for a Safer World was created in 2013. Although legally independent of Interpol, the relationship between the two is close enough for Interpol's president to obtain in 2015 the departure of HSBC CEO from the foundation board after the Swiss Leaks allegations.[27]

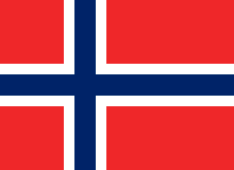

From 2004 to 2010, Interpol's external auditors was the French Court of Audit.[28][29] In November 2010, the Court of Audit was replaced by the Office of the Auditor General of Norway for a three-year term with an option for a further three years.[30][31]

Criticism

Despite its politically neutral stance, some have criticized the agency for its role in arrests that critics contend were politically motivated. In the year 2008, the office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees pointed to the problem of arrests of refugees on the request of Interpol[32] in connection with politically motivated charges. In their declaration, adopted in Oslo (2010),[33] Monaco (2012),[34] Istanbul (2013),[35] and Baku (2014),[36] the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly criticized some OSCE member States for their abuse of mechanisms of the international investigation and urged them to support the reform of Interpol in order to avoid politically motivated prosecution. The Istanbul Declaration of the OSCE cited specific cases of such prosecution, including those of the Russian activist Petr Silaev, financier William Browder, businessman Ilya Katsnelson, Belarusian politician Ales Michalevic, and Ukrainian politician Bohdan Danylyshyn. The resolution of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe of 31 January 2014 criticizes the mechanisms of operation of the Commission for the Control of Interpol's files, in particular, non-adversarial procedures and unjust decisions.[37][38] In 2014, PACE adopted a decision to thoroughly analyse the problem of the abuse of Interpol and to compile a special report on this matter.[39] In May 2015, within the framework of the preparation of the report, the PACE Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights organized a hearing, during which both representatives of NGOs and Interpol had the opportunity to speak.[40]

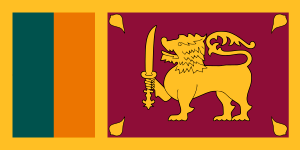

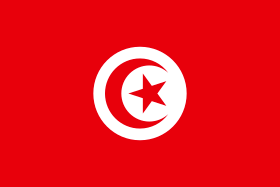

Organizations, such as the Open Dialog Foundation,[41] Fair Trials International,[42] Centre for Peace Studies,[43] International Consortium of Investigative Journalists[44] indicate that non-democratic states use Interpol in order to harass opposition politicians, journalists, human rights activists and businessmen. According to them, countries that frequently abuse the Interpol system include: China,[45] Russia, Iran, Turkey, Kazakhstan, Belarus, Tunisia.[41][42][44]

The Open Dialog Foundation's report analysed 44 high-profile political cases, which went through the Interpol system.[41] A number of persons who have been granted refugee status in the EU and the US, including: Russian businessman Andrey Borodin,[46] Chechen Arbi Bugaev,[47] the Kazakh opposition politician Mukhtar Ablyazov[48] and his associate Artur Trofimov,[49] a journalist from Sri Lanka Chandima Withana[50] continue to remain on the public Interpol list. Some of the refugees remain on the list of Interpol even after courts have refused to extradite them to a non-democratic state (for example, Pavel Zabelin,[51] a witness in the case of Mikhail Khodorkovsky, Alexandr Pavlov,[52] former security chief of the Kazakh oppositionist Ablyazov).

Interpol has recognized some requests to include persons on the wanted list as politically motivated, e.g., Indonesian activist Benny Wenda, Georgian politician Givi Targamadze,[53] ex-president of Georgia Mikheil Saakashvili,[54] ex-president of Honduras Manuel Zelaya Rosales;[55] these persons have been removed from the wanted list. However, in most cases, Interpol removes a "red notice" against refugees only after an authoritarian state closes a criminal case or declares amnesty (for example, the cases of Russian activists, and political refugees: Petr Silaev, Denis Solopov, Aleksey Makarov, and Turkish sociologist Pinar Selek).[56][57][58][59] The election of Meng Hongwei as president and Alexander Prokopchuk, a Russian, as vice president of Interpol for Europe drew criticism in western media and raised fears of Interpol accepting politically motivated requests from China and Russia.[60][61][62]

Refugees who are included in the list of Interpol can be arrested when crossing the border.[42] The procedure for filing an appeal with Interpol is a long and complex one. For example, the Venezuelan journalist Patricia Poleo and a colleague of Kazakh activist Ablyazov, Tatiana Paraskevich, who were granted refugee status, sought to overturn the politically motivated request for as long as one and a half years, and six months, respectively.[63][64][65]

In 2013, Interpol was criticised over its multimillion-dollar deals with such private sector bodies as FIFA, Philip Morris, and the pharmaceutical industry. The criticism was mainly about the lack of transparency and potential conflicts of interest such as Codentify.[66][67][68][69][70][71] After the 2015 FIFA scandal, the organization has severed ties with all the private-sector bodies that evoked such criticism, and has adopted a new and transparent financing framework.

In 2016, Taiwan criticised Interpol for turning down Taiwan's application to join the General Assembly as an observer.[72] The United States supports Taiwan's participation, and the U.S. Congress passed legislation directing the Secretary of State to develop a strategy to obtain observer status for Taiwan.[73]

According to Stockholm Center for Freedom's report that was issued on September 2017, Turkey has weaponized Interpol mechanisms to hunt down legitimate critics and opponents in violation of Interpol's own constitution. The report lists abuse cases where not only arrest warrants but also revocation of travel documents and passports were used by Turkey as persecution tool against critics and opponents. The harassment campaign targeted foreign companies as well.[74]

On 25 July 2014, despite Interpol's Constitution prohibiting them from undertaking any intervention or activities of a political or military nature,[75] the Ukrainian nationalist paramilitary leader Dmytro Yarosh was placed on Interpol's international wanted list at the request of Russian authorities,[76] which made him the only person wanted internationally after the beginning of the conflict between Ukraine and Russia in 2014. For a long time, Interpol refused to place former President of Ukraine Viktor Yanukovych on the wanted list as a suspect in the mass killing of protesters during Euromaidan.[77][78] Yanukovych was eventually placed on the wanted list on 12 January 2015.[79] However, on 16 July 2015, after an intervention of Joseph Hage Aaronson LLP, the British law firm hired by the former Ukrainian President Yanukovych, the international arrest warrant against the former president of Ukraine was suspended pending further review.[80] In December 2014, the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) liquidated a sabotage and reconnaissance group that was led by a former agent of the Ukrainian Bureau of Interpol that also has family relations in the Ukrainian counter-intelligence agencies.[81] In 2014, Russia made attempts to place on the Interpol wanted list Ukrainian politician Ihor Kolomoyskyi and Ukrainian civic activist Pavel Ushevets, subject to criminal persecution in Russia following his pro-Ukrainian art performance in Moscow.[82]

According to The Open Dialog Foundation, Russia and other former Soviet republics like Azerbaijan, Belarus and Kazakhstan frequently misuse the Interpol system. The foundation's reports cite 44 politically motivated cases which have passed through the Interpol system. Of these, 18 cases originated in Russia, 10 in Kazakhstan and five in Belarus.[83]

Reform of Interpol mechanisms

From 1–3 July 2015, Interpol organized a session of the Working Group on the Processing of Information, which was formed specifically in order to verify the mechanisms of information processing. The Working Group heard the recommendations of civil society as regards the reform of the international investigation system and promised to take them into account, in light of possible obstruction or refusal to file crime reports nationally.[84]

Human rights organization, The Open Dialog Foundation, recommended that Interpol, in particular: create mechanism for the protection of rights of people having international refugee status; initiate closer cooperation of the Commission for the Control of Files with human rights NGO and experts on asylum and extradition; enforce sanctions for violations of Interpol's rules; strengthen cooperation with NGOs, the UN, OSCE, the PACE and the European Parliament.[85]

Fair Trials International proposed to create effective remedies for individuals who are wanted under a Red Notice on unfair charges; to penalize nations which frequently abuse the Interpol system; to ensure more transparency of Interpol's work.[86]

The Centre for Peace Studies also created recommendations for Interpol, in particular to delete Red Notices and Diffusions for people who were granted refugee status according to 1951 Refugee Convention issued by their countries of origin, and to establish an independent body to review Red Notices on a regular basis.[43]

Emblem

The current emblem of Interpol was adopted in 1950 and includes the following elements:[4]

- the globe indicates worldwide activity

- the olive branches represent peace

- the sword represents police action

- the scales signify justice

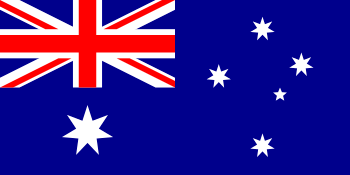

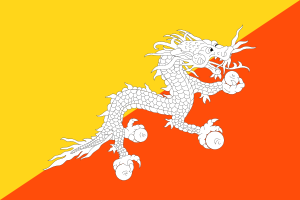

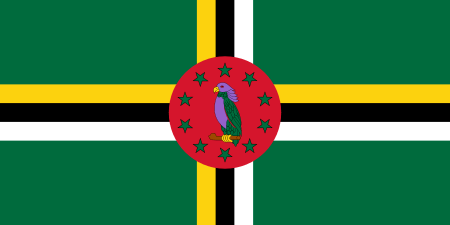

Members

.svg.png)

Sub-bureaus

UN member states without membership

Partially recognized states and entities without membership or sub-bureau status

Unrecognized states without membership or sub-bureau status

Offices

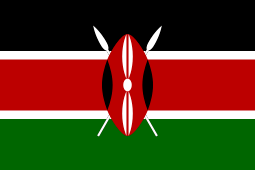

In addition to its General Secretariat headquarters in Lyon, Interpol maintains seven regional bureaus:[1]

- Buenos Aires, Argentina

- San Salvador, El Salvador

- Yaoundé, Cameroon

- Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire

- Nairobi, Kenya

- Harare, Zimbabwe

- Bangkok, Thailand (Liaison Office)

- Belgium, Brussels Liaison office

- Kingdom of the Netherlands, Den Haag Europol

Interpol's Command and Coordination Centres offer a 24/7 point of contact for national police forces seeking urgent information or facing a crisis. The original is in Lyon with a second in Buenos Aires added in September 2011. A third was opened in Singapore in September 2014.[87]

Interpol opened a Special Representative Office to the United Nations in New York in 2004[88] and to the European Union in Brussels in 2009.[89]

The organization has constructed the Interpol Global Complex for Innovation (IGCI) in Singapore to act as its research and development facility, and a place of cooperation on digital crimes investigations. It was officially opened in April 2015, but had already become active beforehand. Most notably, a worldwide takedown of the SIMDA botnet infrastructure was co-ordinated and executed from IGCI's Cyber Fusion Centre in the weeks before the opening, as was revealed at the launch event.[90]

Secretaries-general and presidents

Secretaries-general since organization's inception in 1923:

| 1923–1946 | |

| 1946–1951 | |

| 1951–1963 | |

| 1963–1978 | |

| 1978–1985 | |

| 1985–2000 | |

| 2000–2014 | |

| 2014– |

Presidents since organization's inception in 1923:

| 1923–1932 | |

| 1932–1934 | |

| 1934–1935 | |

| 1935–1938 | |

| 1938–1940 | |

| 1940–1942 | |

| 1942–1943 | |

| 1943–1945 | |

| 1945–1956 | |

| 1956–1960 | |

| 1960–1963 | |

| 1963–1964 | |

| 1964–1968 | |

| 1968–1972 | |

| 1972–1976 | |

| 1976–1980 | |

| 1980–1984 | |

| 1984–1988 | |

| 1988–1992 | |

| 1992–1994 | |

| 1994–1996 | |

| 1996–2000 | |

| 2000–2004 | |

| 2004–2008 | |

| 2008 (acting) | |

| 2008–2012 | |

| 2012–2016 | |

| 2016–2018 | |

| 2018 (acting) |

See also

- Cybercrime

- Europol, a similar EU-wide organization.

- Intelligence assessment

- International Criminal Court

- Interpol notice

- Interpol Terrorism Watch List

- Interpol Travel Document

- InterPortPolice

- UN Police

Notes

- ↑ Taiwan was an Interpol member as the Republic of China until 1984, when it was replaced by the People's Republic of China. Taiwan was offered an option to continue as China's sub-bureau under name "Taiwan, China", but as this could imply that Taiwan was part of the People's Republic of China, it refused and withdrew from the organization.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Annual Report 2013" (PDF). Interpol. 2014. p. 9. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- 1 2 "Constitution of the International Criminal Police Organization – INTERPOL" (PDF). INTERPOL. 1956. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 February 2016. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- ↑ "General Regulations of the International Criminal Police Organization – INTERPOL" (PDF). Interpol, Office of Legal Affairs. 1956. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 February 2016. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- 1 2 "Name and logo". INTERPOL. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ↑ "Germany's Jurgen Stock new INTERPOL chief". Sky News Australia. APP. 8 November 2014. Archived from the original on 10 November 2014. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- ↑ "China accuses ex-Interpol chief Meng of bribery and corruption". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ↑ "Neutrality (Article 3 of the Constitution)". INTERPOL. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ↑ "War crimes". INTERPOL. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ↑ Deflem, M. (2000). "Bureaucratization and Social Control: Historical Foundations of International Police Cooperation". Law & Society Review. 34 (3): 739–778. doi:10.2307/3115142. JSTOR 3115142.

- 1 2 "Interpol: Frequently Asked Questions" (PDF). Fair Trials International. November 2011. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ↑ "Interpol Member States: The United Kingdom". Interpol. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ↑ "Interpol Member States: The United States". Interpol. Retrieved 5 January 2012.

- ↑ Deflem, Mathieu (2002). "The Logic of Nazification: The Case of the International Criminal Police Commission('Interpol')". International Journal of Comparative Sociology. 43 (1): 21. doi:10.1177/002071520204300102. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ↑ Barnett, M.; Coleman, L. (2005). "Designing Police: INTERPOL and the Study of Change in International Organizations". International Studies Quarterly. 49 (4): 593. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2478.2005.00380.x.

- ↑ "Ex-S Africa police chief convicted". Al Jazeera. 2 July 2010. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- ↑ Craig Timberg (13 January 2008). "S. African Chief of Police Put On Leave". The Washington Post. Rustenburg. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ↑ "INTERPOL President Jackie Selebi resigns from post". Lyon: INTERPOL. 13 January 2008. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ↑ "France's Ballestrazzi becomes first female President of INTERPOL". Rome: Interpol. 8 November 2012. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

- ↑ "Interpol: Mireille Ballestrazzi". Interpol. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ↑ "Interpol: President". Interpol. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ↑ "Interpol plea on missing president". BBC News. 2018-10-06. Retrieved 2018-10-06.

- ↑ "French police launch investigation after Interpol chief goes missing for a week in China". The Independent. Retrieved 2018-10-06.

- 1 2 3 Helmut K. Anheier; Mark Juergensmeyer (2012). Encyclopedia of Global Studies. SAGE Publications. pp. 956–958. ISBN 978-1-4129-6429-6. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ↑ Stearns, Peter N. (2008). Oxford Encyclopedia of the Modern World. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195176322.001.0001. ISBN 9780195176322.

- ↑ "INTERPOL issues its first ever passports". Singapore: INTERPOL. 13 October 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ↑ Ravid, Barak (2017-09-27). "Interpol Votes to Accept 'State of Palestine' as Member Country". Haaretz. Retrieved 2017-09-27.

- ↑ "Interpol foundation shows HSBC boss the door". swissinfo.ch. Swissinfo. February 24, 2015. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ↑ "AG-2004-RES-05: Appointment of Interpol External Auditor" (PDF). Cancún: INTERPOL. 8 October 2004. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ↑ "Questions and Answers: What is Canada's financial contribution to INTERPOL?". Royal Canadian Mounted Police. 17 March 2010. Archived from the original on 25 March 2017. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ↑ "Financial Statements for the year ended 31 December 2011" (PDF). Interpol. 25 May 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ↑ "Audit assignments and secondments". Riksrevisjonen – Office of the Auditor General of Norway. Archived from the original on 1 July 2013. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ↑ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (18 January 2008). ""Terrorism as a Global Phenomenon", UNHCR presentation to the Joint Seminar of the Strategic Committee on Immigration, Frontiers and Asylum (SCIFA) and Committee on Article 36 (CATS)" (PDF). UNHCR. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ↑ "2010 Oslo Annual Session". oscepa.org.

- ↑ "Se confirma victoria europeísta en elecciones ucranianas avaladas por la OSCE" [Europeanist victory confirmed in Ukrainian elections endorsed by the OSCE] (in Spanish). OSCE PA. 27 October 2014. Archived from the original on 19 September 2015.

- ↑ "Kiew hat ein neues Parlament, aber keine Aufbruchstimmung" [Kiev has a new parliament, but no lift in mood] (in German). OSCE PA. 27 October 2014. Archived from the original on 19 September 2015.

- ↑ "2014 Baku Annual Session". oscepa.org.

- ↑ Beneyto, José María (17 December 2013). "Doc. 13370: Accountability of international organisations for human rights violations" (PDF). Council of Europe. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ↑ "Vote on Resolution: Assembly's voting results: Vote of José María BENEYTO (EPP/CD)". assembly.coe.int. 2014. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ↑ "Parliamentary Assembly". coe.int.

- ↑ "Synopsis of the meeting held in Yerevan, Armenia on 19–20 May 2015" (PDF). Council of Europe. 26 May 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- 1 2 3 "The report: The Interpol system is in need of reform". The Open Dialog Foundation.

- 1 2 3 "Policy report: INTERPOL and human rights". FairTrials.org. 26 November 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- 1 2 "Safeguarding non refoulement within Interpol's mechanisms". Safeguarding non refoulement within Interpol’s mechanisms – CMS.

- 1 2 "Interpol's Red Notices used by some to pursue political dissenters, opponents". International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

- ↑ "Interpol Is Helping Enforce China's Political Purges".

- ↑ "INTERPOL". interpol.int.

- ↑ "INTERPOL". interpol.int.

- ↑ "INTERPOL". interpol.int.

- ↑ "INTERPOL". interpol.int.

- ↑ "INTERPOL". interpol.int.

- ↑ "INTERPOL". interpol.int.

- ↑ "INTERPOL". interpol.int.

- ↑ "Интерпол и Литва сочли преследование Таргамадзе политическим". lenta.ru.

- ↑ "Archived copy" Прес-служба Одеської ОДА про рішення Інтерполу [Press service of the Odessa Regional State Administration on the Interpol decision]. odessa.gov.ua (in Ukrainian). 31 July 2015. Archived from the original on 16 March 2016. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- ↑ "PR065 / 2009 / News / News and media / Internet / Home – INTERPOL". interpol.int. Archived from the original on 10 September 2015. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- ↑ "INTERPOL reinstates alert against Russian refugee". FairTrials.org.

- ↑ "Грани.Ру: Фигуранты 'химкинского дела' Солопов и Силаев амнистированы – Амнистия". grani.ru.

- ↑ "В ФРГ арестован беженец из России Алексей Макаров. – Русская планета". rusplt.ru.

- ↑ "Turkey: Sociologist Pınar Selek acquitted for the fourth time in 16 years". pen-international.org. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- ↑ Robbie Gramer (10 November 2016). "China and Russia Take the Helm of Interpol". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 14 February 2017. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- ↑ "China to push for greater cooperation on graft, terrorism at Interpol meeting". Reuters. 24 September 2017. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- ↑ Jonathan Kaiman (10 November 2016). "Chinese public security official named head of Interpol, raising concerns among human rights advocates". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 26 July 2017. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- ↑ Ida Karlsson. "Interpol accused of undermining justice". aljazeera.com.

- ↑ "UA:295/13 Index:EUR 71/008/2013 – Urgent Action: Woman faces torture if extradited" (PDF). Amnesty International. 21 October 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ↑ "Written question – Impact of Interpol Red Notice on Schengen Information System- E-009196/2015". europa.eu.

- ↑ Mathieu Martinière; Robert Schmidt (30 October 2013). "The smoke and mirrors of the tobacco industry's funding of Interpol". mediapart.fr. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- ↑ Trina Tune. "Industry-INTERPOL deal signals challenges to illicit trade protocol". fctc.org.

- ↑ Robert Schmidt; Mathieu Martiniere (21 October 2013). "Interpol: Wer hilft hier wem?". Die Zeit.

- ↑ Robert Schmidt; Mathieu Martiniere (7 June 2013). "Tabakindustrie: Interpol, die Lobby und das Geld". Die Zeit.

- ↑ Luk Joossens; Anna B Gilmore (12 March 2013). "The transnational tobacco companies' strategy to promote Codentify, their inadequate tracking and tracing standard" (PDF). tobaccocontrol.bmj.com. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ↑ Robert Schmidt; Mathieu Martiniere. "Interpol : le lobby du tabac se paie une vitrine". lyoncapitale.fr.

- ↑ "Taiwan excluded from Interpol meet".

- ↑ "S.2426 – A bill to direct the Secretary of State to develop a strategy to obtain observer status for Taiwan in the International Criminal Police Organization, and for other purposes". 2016-03-18.

- ↑ Stockholm Center for Freedom (September 2017). "Abuse of the Interpol System by Turkey" (PDF). Stockholm Center for Freedom. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ↑ "Neutrality (Article 3 of the Constitution)". INTERPOL.int. 1956. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- ↑ Mark Rachkevych (25 July 2014). "Interpol issues wanted notice for nationalist leader Yarosh at Russia's behest". KyivPost. Archived from the original on 25 July 2014.

- ↑ Інтерпол відмовився оголосити у розшук Януковича і К° [Interpol has declined putting Yanukovych and Co on wanted list] (in Ukrainian). Ukrinform. 8 December 2014. Archived from the original on 10 August 2015.

- ↑ МВС розслідує політичні мотиви Інтерполу у справах Януковича і Ко [Ministry of Internal Affairs is investigating Interpol's political motives regarding Yanukovych and Co] (in Ukrainian). Ukrinform. 17 November 2014. Archived from the original on 3 July 2015.

- ↑ "YANUKOVYCH, VIKTOR: Wanted by the judicial authorities of Ukraine for prosecution / to serve a sentence". 2014.

- ↑ "Ex-Ukrainian president Yanukovych no longer on Interpol wanted list". uatoday.tv. Archived from the original on 2015-07-22.

- ↑ Групою бойовиків керував колишній працівник Інтерполу – СБУ [Group of militants was run by a former employee of Interpol – SBU]. Ukrayinska Pravda (in Ukrainian). 19 December 2014. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- ↑ Andriy Osavoliyk (17 September 2014). "Russia continues to abuse the mechanisms of international criminal prosecution". The Open Dialog Foundation. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- ↑ Anna Koj (10 March 2015). "Interpol needs reform. ODF appeals to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees". The Open Dialog Foundation. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- ↑ "Working group starts review of INTERPOL's information processing mechanisms". interpol.int. 3 July 2015. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- ↑ Lyudmyla Kozlovska (14 July 2015). "ODF drafted recommendations on the reform of Interpol". The Open Dialog Foundation. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- ↑ "Fair Trials Makes Recommendations to Interpol on Red Notice Abuse". FairTrials.org. 28 July 2015. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- ↑ "Command & Coordination Centre". Interpol. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ↑ "Order on Interpol Work Inside U.S. Irks Conservatives". The New York Times. New York. 30 December 2009.

- ↑ "Official opening of INTERPOL's office of its Special Representative to the European Union marks milestone in co-operation". Brussels: Interpol. 25 September 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ↑ "S'pore, Interpol reaffirm excellent partnership". Channel NewsAsia. Singapore: MediaCorp. 22 May 2013. Archived from the original on 10 July 2013. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Interpol. |