Indian provincial elections, 1937

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

1585 provincial seats contested | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

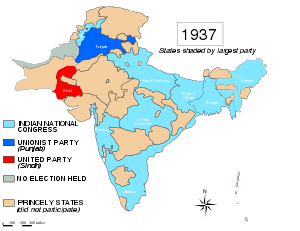

Provincial elections were held in British India in the winter of 1936-37 as mandated by the Government of India Act 1935. Elections were held in eleven provinces - Madras, Central Provinces, Bihar, Orissa, United Provinces, Bombay Presidency, Assam, NWFP, Bengal, Punjab and Sindh.

The final results of the elections were declared in February 1937. The Indian National Congress emerged in power in eight of the provinces - the three exceptions being Bengal, Punjab, and Sindh. The All-India Muslim League failed to form the government in any province.

The Congress ministries resigned in October and November 1939, in protest against Viceroy Lord Linlithgow's action of declaring India to be a belligerent in the Second World War without consulting the Indian people.

Election results

The 1937 election was the first in which large masses of Indians were eligible to participate. An estimated 30.1 million persons, including 4.25 million women, had acquired the right to vote (12% of the total population), and 15.5 million of these, including 917,000 women, participated to exercise their franchise. Nehru admitted that while the elections were on a restricted franchise, they were a big improvement as compared to earlier elections conducted by the British raj that had been extremely restricted.[1]

The results were in favour of the Indian National Congress. Of the total of 1,585 seats, it won 707 (44.6%). Among the 864 seats assigned "general" constituencies, it contested 739 and won 617. Of the 125 non-general constituencies contested by Congress, 59 were reserved for Muslims and in those the Congress won 25 seats, 15 of them in the entirely-Muslim North-West Frontier Province. The All-India Muslim League won 106 seats (6.7% of the total), placing it as second-ranking party. The only other party to win more than 5 percent of the assembly seats was the Unionist Party (Punjab), with 101 seats.[2]

Neither the Muslim League nor the Congress did well in the Muslim constituencies. While the Muslim League fared better on Muslim seats from the non-Muslim majority provinces, its performance was less impressive in the Muslim majority provinces such as Punjab and Bengal. The Congress was also unable to show popularity among Muslims. The elections showed that Muslims thought along provincial or local lines and were less interested in all-India matters.[3]

Legislative Assemblies

| Province | Congress | Muslim League | Other parties | Independents | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assam | 33 | 10 | 24 (Muslim Party) 14 (Non-Congress) | 27 | 108 |

| Bengal | 54 | 37 | 36 (Krishak Praja Party) 10 (Independent Muslims) | 113 | 250 |

| Bihar | 92 | 20 (Muslim Independent Party) 05 (Muslim United Party) 03 (Majlis-e-Ahrar-e-Islam) | 32 | 152 | |

| Bombay | 86 | 18 | 14 (Ambedkarites) 9 (Non-Brahmin) 6 (Other) | 42 | 175 |

| Central Provinces | 70 | 5 | 8 (Muslim Parliamentary Board) 8 (Other) | 21 | 112 |

| Madras | 159 | 9 | 21 (Justice Party) | 26 | 215 |

| North West Frontier Province | 19 | 7 (Hindu-Sikh Nationalists) | 24 | 50 | |

| Orissa | 36 | 14 | 10 | 60 | |

| Punjab | 18 | 1 | 95 (Unionist Party) 14 (Khalsa National Board) 11 (Hindu Election Board) 10 (Akalis) 4 (Majlis-e-Ahrar-e-Islam) | 22 | 175 |

| Sind | 7 | 17 (United Party) 16 (Ghulam Husain's) 12 (Hindu) 3 (Europeans) | 5 | 60 | |

| United Provinces | 133 | 26 | 22 (National Agriculturists) | 47 | 228 |

| Total | 707 | 106 | 397 | 385 | 1585 |

Legislative Councils

| Province | Congress | Muslim League | Other parties | Independents | Europeans | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assam | 10 (Non-Congress) 6 (Muslim Party) | 2 | 3 | 21 | ||

| Bengal | 9 | 7 | 9 (Krishak Praja Party) | 32 | 6 | 63 |

| Bihar | 8 | 2 (United) | 16 | 3 | 29 | |

| Bombay | 13 | 2 | 2 (Democratic Swaraj) | 9 | 4 | 30 |

| Madras | 26 | 3 | 5 (Justice Party) | 12 | 8 | 54 |

| United Provinces | 8 | 4 (National Agriculturists) | 40 | 8 | 60 | |

| Total | 64 | 12 | 38 | 111 | 32 | 257 |

Madras Presidency

In Madras, the Congress won 74% of all seats, eclipsing the incumbent Justice Party (21 seats).[2]

Sindh

The Sind Legislative Assembly had 60 members. The Sind United Party emerged the leader with 22 seats, and the Congress secured 8 seats. Mohammad Ali Jinnah had tried to set up a League Parliamentary Board in Sindh in 1936, but he failed, though 72% of the population was Muslim.[4] Though 34 seats were reserved for Muslims, the Muslim League could secure none of them.[5]

United Provinces

The UP legislature consisted of a Legislative Council of 52 elected and 6 or 8 nominated members and a Legislative Assembly of 228 elected members: some from exclusive Muslim constituencies, some from "General" constituencies, and some "Special" constituencies.[6] The Congress won a clear majority in the United Provinces, with 133 seats,[7] while the Muslim League won only 27 out of the 64 seats reserved for Muslims.[8]

Assam

In Assam, the Congress won 33 seats out of a total of 108 making it the single largest party, though it was not in a position to form a ministry. The Governor called upon Sir Muhammad Sadulla, ex-Judicial Member of Assam and Leader of the Assam Valley Muslim Party to form the ministry.[9] The Congress was a part of the ruling coalition.

Bombay

In Bombay, the Congress fell just short of gaining half the seats. However, it was able to draw on the support of some small pro-Congress groups to form a working majority. B.G. Kher became the first Chief Minister of Bombay.

Other provinces

In three additional provinces, Central Provinces, Bihar, and Orissa, the Congress won clear majorities. In the overwhelmingly Muslim North-West Frontier Province, Congress won 19 out of 50 seats and was able, with minor party support, to form a ministry.[10]

The Unionist Party under Sikander Hyat Khan formed the government in Punjab with 95 out of 175 seats. The Congress won 18 seats and the Akali Dal, 10.[11] In Bengal, though the Congress was the largest party (with 54 seats), The Krishak Praja Party of A. K. Fazlul Huq (with 36 seats) was able to form a coalition government.[12]

Muslim League

The election results were a blow to the League. After the election, Muhammad Ali Jinnah of the League offered to form coalitions with the Congress. The League insisted that the Congress should not nominate any Muslims to the ministries, as it (the League) claimed to be the exclusive representative of Indian Muslims. This was not acceptable to the Congress, and it declined the League's offer. The elections too brought the League with a few benefits: ● The party learned a great deal about how to contest elections. ● The League now knew that its (League's) support lay more in areas where Muslims were in minority, rather than a majority. ● The League also realised that they had an 'image problem'. Its leaders were seen as aristocrats and princes, whereas many Muslims at that time were poor and illiterate.

Resignation of Congress ministries

Viceroy Linlithgow declared India at war with Germany on 3 September 1939.[13] The Congress objected strongly to the declaration of war without prior consultation with Indians. The Congress Working Committee suggested that it would cooperate if there a central Indian national government were formed, and a commitment were made to India's independence after the war.[14] The Muslim League promised its support to the British,[15] with Jinnah calling on Muslims to help the Raj by "honourable co-operation" at the "critical and difficult juncture," while asking the Viceroy for increased protection for Muslims.[16]

The government did not come up with any satisfactory response. Viceroy Linlithgow could only offer to form a 'consultative committee' for advisory functions. Thus, Linlithgow refused the demands of the Congress. On 22 October 1939, all Congress ministries were called upon to tender their resignations. Both Viceroy Linlithgow and Muhammad Ali Jinnah were pleased with the resignations.[13][14] On 2 December 1939, Jinnah put out an appeal, calling for Indian Muslims to celebrate 22 December 1939 as a "Day of Deliverance" from Congress:[17]

I wish the Musalmans all over India to observe Friday 22 December as the "Day of Deliverance" and thanksgiving as a mark of relief that the Congress regime has at last ceased to function. I hope that the provincial, district and primary Muslim Leagues all over India will hold public meetings and pass the resolution with such modification as they may be advised, and after Jumma prayers offer prayers by way of thanksgiving for being delivered from the unjust Congress regime.

References

- ↑ Nehru, Jawaharlal (1 November 2004). The Discovery of India. Allahabad: Penguin Books. p. 59. ISBN 0143031031.

- 1 2 Joseph E. Schwartzberg. "Schwartzberg Atlas". A Historical Atlas of South Asia. Retrieved 2012-04-05.

- ↑ Pandey, Deepak (1978). "Congress-Muslim League Relations 1937-39: 'The Parting of the Ways'". Modern Asian Studies. 12 (4): 629–654.

The Muslim-League, on the other hand, did not fare well at all, especially in the Muslim majority provinces of the Punjab and Bengal. Although it did better in the non-Muslim provinces, yet that was not enough to enable the League to boast of being the sole representative organization of the Muslims. The success of provincial parties like the Krishak Lok Party in Bengal and the Unionist Party in the Punjab showed that the Muslim electorates still thought in terms of ‘provincial’ or ‘local’ considerations, and were not moved so much by all-India issues. What was true of the League was also true of the Congress so far as the Muslims were concerned. The latter, too, was not able to capture Muslim seats in numbers adequate enough to demonstrate its popularity amongst Muslims.

- ↑ Jalal, Ayesha (1994). The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League and the Demand for Pakistan. Cambridge University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-521-45850-4.

- ↑ Afzal, Nasreen. Role of Sir Abdullah Haroon in Politics of Sindh (1872-1942) pp. 185

- ↑ Reeves, P. D. (1971). "Changing Patterns of Political Alignment in the General Elections to the United Provinces Legislative Assembly, 1937 and 1946". Modern Asian Studies. 5 (2): 111–142. doi:10.1017/S0026749X00002973. JSTOR 312028.

- ↑ Visalakshi Menon. "From movement to government: the Congress in the United Provinces, 1937-42", Sage Publications, 2003. pp 60

- ↑ Abida Shakoor. "Congress-Muslim League tussle 1937-40: a critical analysis", Aakar Books, 2003, pp 90

- ↑ "Ministry-making in Assam". The Indian Express. 13 March 1937.

- ↑ Schwartzberg Atlas - Digital South Asia Library. Dsal.uchicago.edu. Retrieved on 2013-12-06.

- ↑ Grewal, J. S. (1990). The Sikhs of the Punjab. The New Cambridge History of India. II.3. Cambridge University Press. p. 170. ISBN 0-521-26884-2.

- ↑ Jalal, Ayesha (1994). The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League and the Demand for Pakistan. Cambridge University Press. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-0-521-45850-4.

- 1 2 Anderson, Ken. "Gandhi - The Great Soul". The British Empire: Fall of the Empire. Retrieved 2007-12-04.

- 1 2 Bandyopadhyay, Sekhara (2004). From Plassey to Partition: A History of Modern India. India: Orient Longman. p. 412. ISBN 978-81-250-2596-2.

- ↑ Schofield, Victoria (2003). Afghan Frontier: Feuding and Fighting in Central Asia. London, New York: Tauris Parke Paperbacks. pp. 232–233. ISBN 1860648959. Retrieved 2007-12-10.

- ↑ Wolpert, Stanley (1998-03-22). "Lecture by Prof. Stanley Wolpert: Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah's Legacy to Pakistan". Jinnah of Pakistan. Humsafar.info. Archived from the original on 27 December 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-11.

- ↑ Nazaria-e-Pakistan Foundation. "Appeal for the observance of Deliverance Day, issued from Bombay, on 2nd December, 1939". Quaid-i-Azam’s Speeches & Messages to Muslim Students. Archived from the original on 2007-07-29. Retrieved 2007-12-04.