Immigration and crime

Immigration and crime refers to perceived or actual relationships between crime and immigration. The academic literature provides mixed findings for the relationship between immigration and crime worldwide, but finds for the United States that immigration either has no impact on the crime rate or that it reduces the crime rate.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10] A meta-analysis of 51 studies from 1994–2014 on the relationship between immigration and crime in different countries found that overall immigration reduces crime, but the relationship is very weak.[11] The over-representation of immigrants in the criminal justice systems of several countries may be due to socioeconomic factors, imprisonment for migration offenses, and racial and ethnic discrimination by police and the judicial system.[10][12][13][14] Research suggests that people tend to overestimate the relationship between immigration and criminality.[15][4][16] The relationship between immigration and terrorism is understudied, but existing research suggests that the relationship is weak and that repression of the immigrants increases the terror risk.[17][18]

Worldwide

Much of the empirical research on the causal relationship between immigration and crime has been limited due to weak instruments for determining causality.[19] According to one economist writing in 2014, "while there have been many papers that document various correlations between immigrants and crime for a range of countries and time periods, most do not seriously address the issue of causality."[10] The problem with causality primarily revolves around the location of immigrants being endogenous, which means that immigrants tend to disproportionately locate in deprived areas where crime is higher (because they cannot afford to stay in more expensive areas) or because they tend to locate in areas where there is a large population of residents of the same ethnic background.[2] A burgeoning literature relying on strong instruments provides mixed findings.[2][3][4][5][6][7][8][20] As one economist describes the existing literature in 2014, "most research for the US indicates that if any, this association is negative... while the results for Europe are mixed for property crime but no association is found for violent crime".[2] Another economist writing in 2014, describes how "the evidence, based on empirical studies of many countries, indicates that there is no simple link between immigration and crime, but legalizing the status of immigrants has beneficial effects on crime rates."[10] A 2009 review of the literature focusing on recent, high-quality studies from the United States found that immigration generally did not increase crime and often decreased it.[9]

The relationship between crime and the legal status of immigrants remains understudied[21][22] but studies on amnesty programs in the United States and Italy suggest that legal status can largely explain the differences in crime between legal and illegal immigrants, most likely because legal status leads to greater job market opportunities for the immigrants.[10][23][24][25][26][27][28]

Existing research suggests that labor market opportunities have a significant impact on immigrant crime rates.[10] Young, male and poorly educated immigrants have the highest individual probabilities of imprisonment among immigrants.[29] Research suggests that the allocation of immigrants to high crime neighborhoods increases individual immigrant crime propensity later in life, due to social interaction with criminals.[30]

Some factors may effect the reliability of data on suspect rates, crime rates, conviction rates and prison populations for drawing conclusions about immigrants’ overall involvement in criminal activity:

- Police practices, such as racial profiling, over-policing in areas populated by immigrants or in-group bias may result in disproportionately high numbers of immigrants among crime suspects.[31][13][32][33][12][34][14][35][36]

- Possible discrimination by the judicial system may result in higher number of convictions.[31][12][14][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45]

- Unfavorable bail and sentencing decisions due to foreigners’ ease of flight, lack of domiciles, lack of regular employment and lack of family able to host the individual can explain immigrants’ higher incarceration rates when compared to their share of convictions relative to the native population.[46][47]

- Natives may be more likely to report crimes when they believe the offender has an immigrant background.[48]

- Imprisonment for migration offenses, which are more common among immigrants, need to be taken account of for meaningful comparisons between overall immigrant and native criminal involvement.[29][14][49][50]

- Foreigners imprisoned for drug offenses may not actually live in the country where they are serving sentences but were arrested while in transit.[29]

- Crimes by short-term migrants, such as tourists, exchange students and transient workers, are counted as crimes by immigrants or foreigners, and gives the impression that a higher share of the migrant population commits crimes (as these short-term migrants are not counted among the foreign-born population).[51]

Terrorism

The relationship between immigration and terrorism remains understudied. A 2016 study finds that a higher level of migration is associated with a lower level of terrorism in the host country, but that migrants from terror-prone states do increase the risk of terrorism in the host country.[18] The authors note though that "only a minority of migrants from high-terrorism states can be associated with increases in terrorism, and not necessarily in a direct way."[18] In 2018, Washington and Lee University law professor Nora V. Demleitner wrote that there is "mixed evidence" as to a relationship between immigration and terrorism.[52] A paper by a group of German political scientists and economists, covering 1980–2010, found that there were more terrorist attacks in countries with a larger number of foreigners, but that, on average, the foreigners were not more likely to become terrorists than the natives.[53][17] The study also found little evidence that terrorism is systematically imported from predominantly Muslim countries.[54][53] The same study found that compared to the average “non-terror-rich” country, migrants from Algeria, Iran, India, Spain, and Turkey were all more likely to be involved in a terrorist attack, while migrants from Angola and Cambodia were less likely than the reference groups to commit terror.The study found that repression of the migrants increased the terror risk.[17][53]

According to Olivier Roy in 2017 analyzing the previous two decades of terrorism in France, the typical jihadist is a second-generation immigrant or convert who after a period of petty crime was radicalized in prison.[55]

Georgetown University terrorism expert Daniel Byman argues that repression of minority groups, such as Muslims, makes it easier for terrorist organizations to recruit from those minority groups.[56]. While French scholar Olivier Roy has argued that the burkini bans and secularist policies of France provoked religious violence in France, French scholar Gilles Kepel responded that Britain has no such policies and still suffered several jihadist attacks in 2017.[57][58]

Asia

Japan

A survey of existing research on immigration and crime in Japan found that "prosecution and sentencing in Japan do seem to result in some disparities by nationality, but the available data are too limited to arrive at confident conclusions about their nature or magnitude".[59]

According to a 1997 news report, a large portion of crimes by immigrants are by Chinese in Japan, and some highly publicized crimes by organized groups of Chinese (often with help of Japanese organized crime) have led to a negative public perception of immigrants.[60]

Malaysia

A 2017 study found that immigration to Malaysia decreases property crime rates and violent crime rates.[61] In the case of property crime rates, this is in part because immigrants improve economic conditions for natives.[61]

Europe

A 2015 study found that the increase in immigration flows into western European countries that took place in the 2000s did "not affect crime victimization, but it is associated with an increase in the fear of crime, the latter being consistently and positively correlated with the natives’ unfavourable attitude toward immigrants."[4] In a survey of the existing economic literature on immigration and crime, one economist describes the existing literature in 2014 as showing that "the results for Europe are mixed for property crime but no association is found for violent crime".[2]

Denmark

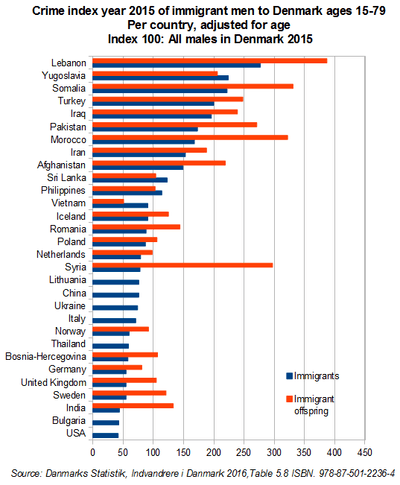

A report by Statistics Denmark released in December 2015 found that 83% of crimes are committed by individuals of Danish origin (88% of the total population), 3% by those of non-Danish Western descent and 14% by individuals of non-Western descent.[63]

Male Lebanese immigrants and their descendants, a big part of them being of Palestinian descent,[63] have, at 257, the highest crime-index among the studied groups, which translates to crime rates 150% higher than the country's average. The index is standardized by both age and socioeconomic status. Men of Yugoslav origin and men originating in Turkey, Pakistan, Somalia and Morocco are associated with high crime-indexes, ranging between 187 and 205, which translate to crime rates about double the country's average. The lowest crime index is recorded among immigrants and descendants originating from the United States. Their crime-index, at 32, is far below the average for all men in Denmark.[63] Among immigrants from China a very small crime-index is recorded as well, at 38.

A 2014 study of the random dispersal of refugee immigrants over the period 1986–1998, and focusing on the immigrant children who underwent this random assignment before the age of 15, suggests that exposure to neighbourhood crime increases individual crime propensity.[30] The share of convicted criminals living in the assignment neighborhood at assignment affects later crime convictions of males, but not of females, who were assigned to these neighborhoods as children.[30] The authors "find that a one standard deviation increase in the share of youth criminals living in the assignment neighborhood, and who committed a crime in the assignment year, increases the probability of a conviction for male assignees by between 5 percent and 9 percent later in life (when they are between 15 and 21 years old)."[30]

One study of Denmark found that providing immigrants with voting rights reduced their crime rate.[64]

At 4%, male migrants aged 15–64 with non-Western backgrounds had twice the conviction rate against the Danish Penal Code in 2018, compared to 2% for Danish men. In a given year, about 13% of all male descendants of non-Western migrants aged 17–24 are convicted against the penal code.[65]

Finland

A 2015 study found that immigrant youth had higher incidence rates in 14 out of 17 delinquent acts. The gap is small for thefts and vandalism, and no significant differences for shoplifting, bullying and use of intoxicants. According to the authors, "weak parental social control and risk routines, such as staying out late, appear to partly explain the immigrant youths’ higher delinquency", and "the relevance of socioeconomic factors was modest".[66]

According to the American Bureau of Diplomatic Security, Estonians and Romanians were the two largest group of foreigners in Finnish prisons.[67]

According to 2014 official statistics, 24% of rapes are estimated to have been committed by individuals with foreign surnames in Finland.[68] For some context, foreign-language speakers and the foreign-born comprised roughly 6% of the Finnish population in 2014, meaning that the percentage of individuals with foreign surnames in Finland is at very least 6%.[69][70] There are great differences in representation between nationalities of rapists: while in 1998 there were no rapists hailing from Vietnam or China, there were many from other countries; 10 times more "foreign-looking" men were accused of rape than the overall percentage of foreigners in Finland.[71]

In 2016, in a report authored by the Police school and the Immigration Service (Migri), 131 Finnish citizens were subjected to sexual assault by asylum migrants of which 8 out of 10 were committed against Finnish women.[72] Almost half the sexual assaults against women the victim was under 18.[72] Iraqis made up 2/3 of the suspects and all the suspects originated in Iraq, Afghanistan, Morocco, Iran, Bangladesh, Somalia or Syria.[72] The investigation also analysed the number of suspects with respect to background, it was found that every fifth Algerian asylum seeker had been suspected of a crime, 15% of Belorussinans, 13% of the Moroccans and less than 10% for other nationalities.[72]

France

A 2009 study found "that the share of immigrants in the population has no significant impact on crime rates once immigrants’ economic circumstances are controlled for, while finding that unemployed immigrants tend to commit more crimes than unemployed non-immigrants."[73]

A study by sociologist Farhad Khosrokhavar, director of studies at the EHESS, found that "Muslims, mostly from North African origin, are becoming the most numerous group in [French prisons]."[74][75] His work has been criticized for taking into account only 160 prisoners in 4 prisons, all close to northern Paris where most immigrants live.[76]

Germany

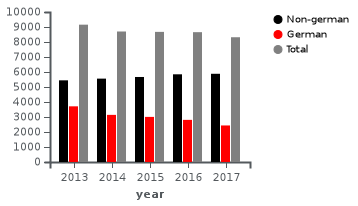

| Number of suspects in organized crime in Germany | |

| |

| Source: BKA[77] | |

In 2017, as in previous years German citizens constituted the largest group of suspects in organised crime trials. The fraction of non-German citizen suspects increased from 67.5% to 70.7% while the fraction of German citizens decreased correspondingly. For the German citizens, 14.9% had a different citizenship at birth.[77]

Published in 2017, the first comprehensive study of the social effects of the one million refugees going to Germany found that it caused "very small increases in crime in particular with respect to drug offenses and fare-dodging."[78][79] A January 2018 Zurich University of Applied Sciences study commissioned by the German government attributed over 90% of a 10% overall rise in violent crime from to 2015 to 2016 in Lower Saxony could to refugees.[80] The study's authors noted that there were great differences between different refugee groups.[81] Refugees from North African countries Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco constituted 0.9% of refugees but represented 17.1% of violent crime refugee suspects and 31% of robbery refugee suspects. The latter corresponds to a 35-fold over-representation. Refugees from Afghanistan, Syria and Iraq represented 54.7% of the total, but represented 16% of refugee robbery suspects and 34.9% violent crime suspects and were thus underrepresented.[82]

A report released by the German Federal Office of Criminal Investigation in November 2015 found that over the period January–September 2015, the crime rate of refugees was the same as that of native Germans.[83] According to Deutsche Welle, the report "concluded that the majority of crimes committed by refugees (67 percent) consisted of theft, robbery and fraud. Sex crimes made for less than 1 percent of all crimes committed by refugees, while homicide registered the smallest fraction at 0.1 percent."[83] According to the conservative newspaper Die Welt's description of the report, the most common crime committed by refugees was not paying fares on public transportation.[84] According to Deutsche Welle's reporting in February 2016 of a report by the German Federal Office of Criminal Investigation, the number of crimes committed by refugees did not rise in proportion to the number of refugees between 2014–2015.[85] According to Deutsche Welle, "between 2014 and 2015, the number of crimes committed by refugees increased by 79 percent. Over the same period the number of refugees in Germany increased by 440 percent."[85]

The U.S. fact-checker Politifact noted that Germany's crime data suggests that the crime rate of the average refugee is lower than that of the average German.[86] In April 2017, the crime figures released for 2016 showed that the number of suspected crimes by refugees, asylum-seekers and illegal immigrants increased by 50 percent.[87] The figures showed that most of the suspected crimes were by repeat offenders, and that 1 percent of migrants accounted for 40 percent of total migrant crimes.[87] From 2016 to 2017, the number of crimes committed by foreigners in Germany decreased by 23%.[88][89][90]

A 2017 study in the European Economic Review found that the German government's policy of immigration of more than 3 million people of German descent to Germany after the collapse of the Soviet Union led to a significant increase in crime.[22] The effects were strongest in regions with high unemployment, high preexisting crime levels or large shares of foreigners.[22]

According to a 2017 study in the European Journal of Criminology, the crime rate was higher among immigrant youths than native youths during the 1990s and 2000s but most of the difference could be explained by socioeconomic factors.[91] The different crime rates narrowed in the last ten years; the study speculates that "a new citizenship law finally granting German-born descendants of guest workers German citizenship, as well as increased integration efforts (particularly in schools) and a stronger disapproval of violence" may have contributed to this narrowing.[91]

DW reported in 2006 that in Berlin, young male immigrants are three times more likely to commit violent crimes than their German peers. Hans-Jörg Albrecht, director of the Max Planck Institute for Foreign and International Criminal law in Freiburg, stated that the "one over-riding factor in youth crime [was] peer group pressure."[92] Whereas the Gastarbeiter in the 50s and 60s did not have an elevated crime rate, second- and third-generation of immigrants had significantly higher crime rates.[93]

Greece

Illegal immigration to Greece has increased rapidly over the past several years. Tough immigration policies in Spain and Italy and agreements with their neighboring African countries to combat illegal immigration have changed the direction of African immigration flows toward Greece. At the same time, flows from Asia and the Middle East—mainly Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Bangladesh—to Greece appear to have increased as well.[94] By 2012 it was estimated that more than 1 million illegal immigrants entered Greece.[94][95] The evidence now indicates that nearly all illegal immigration to the European Union flows through the country's porous borders. In 2010, 90 percent of all apprehensions for unauthorized entry into the European Union took place in Greece, compared to 75 percent in 2009 and 50 percent in 2008.[94]

In 2010, 132,524 persons were arrested for "illegal entry or stay" in Greece, a sharp increase from 95,239 in 2006. Nearly half of those arrested (52,469) were immediately deported, the majority of them being Albanians.[94] Official statistics show that immigrants are responsible for about half of the criminal activity in Greece.[95]

Ireland

Foreigners are under-represented in the Irish prison population, according to 2010 figures.[27]

Italy

A study of immigration to Italy during the period 1990–2003 found that "immigration increases only the incidence of robberies, while leaving unaffected all other types of crime. Since robberies represent a very minor fraction of all criminal offenses, the effect on the overall crime rate is not significantly different from zero."[3] Over the period 2007-2016, the crime rate among foreigners decreased by around 65%.[96]

A study of Italy before and after the January 2007 European Union enlargement found that giving legal status to the previously illegal immigrants from the new EU members states led to a "50 percent reduction in recidivism".[23] The authors find that "legal status... explains one-half to two-thirds of the observed differences in crime rates between legal and illegal immigrants".[23] A study on the 2007 so-called "click day" amnesty for undocumented immigrants in Italy found that the amnesty reduced the immigrant crime rate.[47] The authors estimate "that a ten percent increase in the share of immigrants legalized in one region would imply a 0.3 percent reduction in immigrants’ criminal charges in the following year in that same region".[47] Research shows that stricter enforcement of migration policy leads to a reduction in the crime rate of undocumented migrants.[97]

According to the latest report by Idos/Unar, immigrants made up 32,6% of prison population in 2015 (four percentage points less than five years before),[98] immigrants making up 8,2% of population in 2015.[99] Prison population data may not give a reliable picture of immigrants' involvement in criminal activity due to different bail and sentencing decisions for foreigners.[47] Foreigners are, for instance, far more overrepresented in the prison population than their share of convictions relative to the native population.[47] According to a 2013 study, the majority of foreign prisoners are held in connection with a drug offence.[14] One out of every nine offences ascribed to foreign prisoners concerns violation of ‘laws governing foreigners’.[14] The 2013 study cites literature that points to discriminatory practices against foreigners by Italian law enforcement, judiciary and penal system.[14]

According to a 2013 report, "undocumented immigrants are responsible for the vast majority of crimes committed in Italy by immigrants... the share of undocumented immigrants varies between 60 and 70 percent for violent crimes, and it increases to 70–85 for property crime. In 2009, the highest shares are in burglary (85), car theft (78), theft (76), robbery (75), assaulting public officer / resisting arrest (75), handling stolen goods (73)."[47]

The 2013 report notes that "immigrants accounted for almost 23 percent of the criminal charges although they represented only 6‐7 percent of the resident population" in 2010.[47]

According to 2007 data, the crime rate of legal immigrants was 1.2–1.4% whereas the crime rate was 0.8% for native Italians. The overrepresentation is partly due to the large number of young legal immigrants, the crime rate is 1.9% for legal immigrants aged 18–44 whereas it is 1.5% for their Italian peers; 0.4% for legal immigrants aged 45–64 years whereas it is 0.7% for their Italian peers; and for those over 65 years old, the crime rates is the same among natives and foreigners. 16.9% of crimes committed by legal immigrants aged 18–44 are linked to violations of immigration laws. By excluding those crimes, the crime rate of legal immigrants aged 18–44 is largely the same as that of same aged Italians.[100]

Netherlands

Non-native Dutch youths, especially young Antillean and Surinamese Rotterdammers, commit more crimes than the average. More than half of Moroccan-Dutch male youths aged 18 to 24 years in Rotterdam have ever been investigated by the police, as compared to close to a quarter of native male youths. Eighteen percent of foreign-born young people aged from 18 to 24 have been investigated for crimes.[101][102]

According to a 2009 report commissioned by Justice Minister Ernst Hirsch Ballin, 63% of the 447 teenagers convicted of serious crime are children of parents born outside the Netherlands. All these cases concern crime for which the maximum jail sentence is longer than eight years, such as robbery with violence, extortion, arson, public acts of violence, sexual assault, manslaughter and murder. The ethnic composition of the perpetrators was: native Dutch – 37%; Moroccans – 14%; Unknown origin – 14%; "other non-Westerners" – 9%; Turkish – 8%; Surinamese – 7%; Antillean – 7%; and "other Westerners" – 4%.[103] In the majority of cases, the judges did not consider the serious offences to be grave enough to necessitate an unconditional jail sentence.[103]

Analysis of police data for 2002 by ethnicity showed that 37.5 percent of all crime suspects living in the Netherlands were of foreign origin (including those of the second generation), almost twice as high as the share of immigrants in the Dutch population. The highest rates per capita were found among first and second generation male migrants of a non‐Western background. Of native male youths between the ages of 18 and 24, in 2002 2.2% were arrested, of all immigrant males of the same age 4.4%, of second generation non-Western males 6.4%. The crime rates for so‐called ‘Western migrants’ were very close to those of the native Dutch. In all groups, the rates for women were considerably lower than for men, lower than one percent, with the highest found among second generation non‐western migrants, 0.9% (Blom et al. 2005: 31).[104]

For Moroccan immigrants, whether they originate from the underdeveloped parts of Morocco has a modest impact on their crime rate. One study finds that "crime rates in the Netherlands are higher among Moroccans who come from the countryside and the Rif, or whose parents do, than among those who come from the urban provinces in Morocco and from outside the Rif, or whose parents do."[105] In 2015, individuals with a Moroccan background were, not taking their age into account, almost six times as likely to be suspected for a crime compared to the native Dutch. Of the first generation 2.52% was suspected of a crime, of the second generation 7.36%, of males 7.78% and women 1.34%.[106]

Using 2015 data, Statistics Netherlands concluded that non-Western male immigrant youths had been relatively often suspected of a crime: 5.42% in the group aged between 18 and 24, compared with 1.92% for native Dutch of the same age. For both male and female non-Western immigrants of all ages combined the numbers were 2.4% for the first generation and 4.54% for the second. The absolute crime rate had dropped by almost a half since the early twenty-first century, for both native Dutch and non-western immigrants.[107] In 2017, a study concluded that asylum seekers in the Netherlands were less criminal than native Dutch with the same combination of age, gender and socio-economic position.[108]

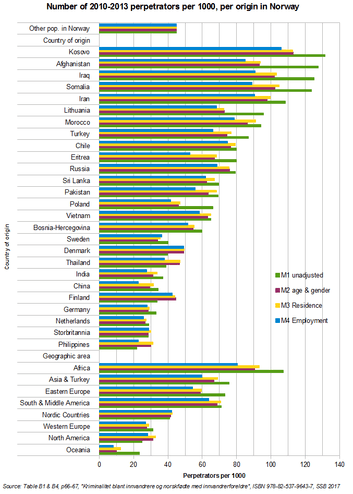

Norway

A 2011 report by Statistics Norway found that immigrants are over-represented in crime statistics but that there is substantial variation by country of origin.[111] The report furthermore found that "the overrepresentation is substantially reduced when adjusting for population structure—for some groups as much as 45 per cent, but there are also some groups where the over-representation still is large."[111] According to the report, the data for 2009 shows that first-generation immigrants from Africa were three times more likely than ethnic Norwegians (or rather individuals who are neither first- nor second-generation immigrants) to be convicted of a felony while Somali immigrants in particular being 4.4 times more likely to be convicted of a felony than an ethnic Norwegian was. Similarly, Iraqis and Pakistanis were found to have rates of conviction for felonies greater than ethnic Norwegians by a factor of 3 and 2.6 respectively. Another finding was that second-generation African and Asian immigrants had a higher rate of convictions for felonies than first-generation immigrants. While first-generation African immigrants had conviction rates for felonies of 16.7 per 1,000 individuals over the age of 15, for second-generation immigrants the rate was 28 per 1,000—an increase of over 60%. And for Asian immigrants an increase from 9.3 per 1,000 to 17.1 per 1,000 was observed. In 2010 13% of sexual crimes charges were filed against first generation immigrants who make up 7.8% of the population—a rate of over-representation of 1.7.[111]

In 2010, a spokesperson for the Oslo Police Department stated that every case of assault rapes in Oslo in the years 2007, 2008 and 2009 was committed by a non-Western immigrant.[112] When only perpetrators in the solved cases were counted, it was found that four of the victims in the 16 unsolved cases described the perpetrator as being of White (not necessarily Norwegian) ethnicity.[113]

A 2011 report by the Oslo Police District shows that of the 131 individuals charged with the 152 rapes in which the perpetrator could be identified, 45.8% were of African, Middle Eastern or Asian origin while 54.2% were of Norwegian, other European or American origin. In the cases of "assault rape", i.e. rape aggravated by physical violence, a category that included 6 of the 152 cases and 5 of the 131 identified individuals, the 5 identified individuals were of African, Middle Eastern or Asian origin. In the cases of assault rape where the individual responsible was not identified and the police relied on the description provided by the victim, 8 of the perpetrators were of African/dark-skinned appearance, 4 were Western/light/Nordic and 4 had an Asian appearance.[114]

In 2018, an investigation into court cases involving domestic violence against children showed that 47% of the cases involved parents who were both born abroad. According to a researcher at Norwegian Police University College the over-representation was due to cultural (honor culture) and legal differences in Norway and foreign countries.[115]

Spain

A 2008 study finds that the rates of crimes committed by immigrants are substantially higher than nationals.[116] The study finds that "the arrival of immigrants has resulted in a lack of progress in the reduction of offences against property and in a minor increase in the number of offences against Collective Security (i.e. drugs and trafficking). In the case of nationals, their contribution to the increase in the crime rate is primarily concentrated in offences against persons."[116] By controlling for socioeconomic and demographic factors, the gap between immigrants and natives is reduced but not fully. The authors also find "that a higher proportions of American, non-UE European, and African immigrants tend to widen the crime differential, the effect being larger for the latter ones".[116] The same paper provides supports for the notion that labour market conditions impact the relationship between crime and immigration. Cultural differences were also statistically detected.[116] This study has been criticized for not using strong instruments for identifying causality: the "instruments (lagged values of the covariates and measures of the service share of GDP in a province) are not convincing in dealing with the endogeneity of migrant location choice."[117]

Spanish National Statistics Institute (INE) published a study that analyzes records in the Register of Convicted in 2008. The data show that immigrants are overrepresented in the crime statistics: 70% of all crimes were committed by Spaniards and 30% by foreigners.[118] Foreigners make up 15% of the population.[118]

Switzerland

In Switzerland, 69.7% of the prison population did not have Swiss citizenship, compared to 22.1% of total resident population (as of 2008). The figure of arrests by residence status is not usually made public. In 1997, when there were for the first time more foreigners than Swiss among the convicts under criminal law (out of a fraction of 20.6% of the total population at the time), a special report was compiled by the Federal Department of Justice and Police (published in 2001) which for the year 1998 found an arrest rate per 1000 adult population of 2.3 for Swiss citizens, 4.2 for legally resident aliens and 32 for asylum seekers. 21% of arrests made concerned individuals with no residence status, who were thus either sans papiers or "crime tourists" without any permanent residence in Switzerland.[119]

A 2016 study found that asylum seekers exposed to conflict during childhood were far more prone to violent crimes than co-national asylum seekers who were not exposed to conflict.[120] The conflict exposed cohorts have a higher propensity to target victims from their own nationality.[120] Offering labor market access to the asylum seekers eliminates the entire effect of conflict exposure on crime propensity.[120]

In 2010, a statistic was published which listed delinquency by nationality (based on 2009 data). To avoid distortions due to demographic structure, only the male population aged between 18 and 34 was considered for each group. From the study, it became clear that crime rate is highly correlated on the country of origin of the various migrant groups. Thus, immigrants from Germany, France and Austria had a significantly lower crime rate than Swiss citizens (60% to 80%), while immigrants from Angola, Nigeria and Algeria had a crime rate of above 600% of that of Swiss population. In between these extremes were immigrants from Former Yugoslavia, with crime rates of between 210% and 300% of the Swiss value.[121]

Sweden

Those with immigrant background are over-represented in Swedish crime statistics, but research shows that socioeconomic factors, such as unemployment, poverty, exclusion language, and other skills explain most of difference in crime rates between immigrants and natives.[13][122][123][124][125][126][127][128]

Recent immigration to Sweden

Crime and immigration is one of the major themes of the 2018 Swedish general election.[129][130]

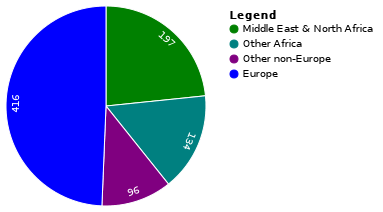

| 2013-2018 birthplace of rapists convicted in Sweden | |

| |

| Total: 843 Source: Swedish Television[131] | |

In 2018, Swedish Television investigative journalism show Uppdrag Granskning analysed the total of 843 district court cases from the five preceding years and found that 58% of all convicted of rape had a foreign background and 40% were born in the Middle East and Africa, with young men from Afghanistan numbering 45 stood out as being the most next most common country of birth after Sweden. When only analysing rape assault (Swedish: överfallsvåldtäkt) cases, that is cases where perpetrator and victim were not previously acquainted, 97 out of 129 were born outside Europe.[131]

Viral falsehoods have circulated in recent years that tie immigrants and refugees to an alleged surge of crime in Sweden.[132][133] According to Jerzy Sarnecki, a criminologist at Stockholm University, "What we’re hearing is a very, very extreme exaggeration based on a few isolated events, and the claim that it’s related to immigration is more or less not true at all."[132][134] According to Klara Selin, a sociologist at the National Council for Crime Prevention, the major reasons why Sweden has a higher rate of rape than other countries is due to the way in which Sweden documents rape ("if a woman reports being raped multiple times by her husband that’s recorded as multiple rapes, for instance, not just one report") and a culture where women are encouraged to report rapes.[132] Stina Holmberg at the National Council for Crime Prevention, noted that "there is no basis for drawing the conclusion that crime rates are soaring in Sweden and that that is related to immigration".[124]

In February 2017, U.S. President Donald Trump asserted that crime was surging in Sweden due to immigration.[135] According to FactCheck.Org, Trump's claim was an exaggeration and noted that "experts said there is no evidence of a major crime wave."[132] According to official statistics, the reported crime rate in Sweden has risen since 2005 whereas annual government surveys show that the number of Swedes experiencing crime remain steady since 2005, even as Sweden has taken in hundreds of thousands of immigrants and refugees over the same period.[135][136][137][138][139] Jerzy Sarnecki, a criminologist at the University of Stockholm, said foreign-born residents are twice as likely to be registered for a crime as native Swedes but that other factors beyond place of birth are at play, such as education level and poverty, and that similar trends occur in European countries that have not taken in a lot of immigrants in recent years.[125]

According to data gathered by Swedish police from October 2015 to January 2016, 5,000 police calls out of 537,466 involved asylum seekers and refugees.[140] According to Felipe Estrada, professor of criminology at Stockholm University, this shows how the media gives disproportionate attention to and exaggerates the alleged criminal involvement of asylum seekers and refugees.[140] Henrik Selin, head of the Department for Intercultural Dialogue at the Swedish Institute, noted that allegations of a surge in immigrant crime after the intake of more than 160,000 immigrants in 2015 have been “highly exaggerated... there is nothing to support the claim that the crime rate took off after the 160,000 came in 2015.” While it’s true that immigrants have been over-represented among those committing crimes—particularly in some suburban communities heavily populated by immigrants, he said—the issue of crime and immigration is complex.[132] Speaking in February 2017, Manne Gerell, a doctoral student in criminology at Malmo University, noted that while immigrants where disproportionately represented among crime suspects, many of the victims of immigrant crimes were other immigrants.[141]

A Swedish Police report from May 2016 found that there have been 123 incidents of sexual molestation in the country's public baths and pools in 2015 (112 of them were directed against girls). In 55% of cases, the perpetrator could be reasonably identified. From these identified perpetrators, 80% were of foreign origin.[142] The same report found 319 cases of sexual assault on public streets and parks in 2015. In these cases, only 17 suspected perpetrators have been identified, 4 of them Swedish nationals with the remainder being of foreign origin. Another 17 were arrested, but not identified.[143]

In March 2018, newspaper Expressen investigated gang rape court cases from the two preceding years and found that there were 43 men having been convicted. Their average age was 21 and 13 were under the age of 18 when the crime was committed. Of the convicted, 40 out of the 43 were either immigrants (born abroad) or born in Sweden to immigrant parents.[144] Another investigation by newspaper Aftonbladet found that of 112 men and boys convicted for gang rape since July 2012, 82 were born outside Europe. The median age of the victims was 15, while 7 out of 10 perpetrators were between 15 to 20.[145] According to professor Christian Diesen, a foreigner may have a lower threshold to commit sexual assault due to having grown up in a misogynist culture where all women outside the home are interpreted as available. Also professor Henrik Tham stated that there was a clear over-representatation of foreigners and cultural differences, while also adding that few cultures allow such behaviour. Professor Jerzy Sarnecki instead emphasized socioeconomic factors and that police may be more diligient in investigating crimes by foreigners.[145]

Past immigration to Sweden

A 2014 survey of several studies found that people with foreign background are, on average, two times more likely to commit crimes than those born in Sweden. This figure has remained stable since the 1970s, despite the changes in numbers of immigrants and their country of origin.[146] Some studies reporting a link on immigration and crime have been criticized for not taking into account the population's age, employment and education level, all of which affect level of crime. In general, research that takes these factors into account does not support the idea that there is a link between immigration and crime.[147]

A 2005 study by the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention found that people of foreign background were 2.5 times more likely to be suspected of crimes than people with a Swedish background, including immigrants being four times more likely to be suspected of for lethal violence and robbery, five times more likely to be investigated for sex crimes, and three times more likely to be investigated for violent assault.[148][149] The report was based on statistics for those "suspected" of offences. The Council for Crime Prevention said that there was "little difference" in the statistics for those suspected of crimes and those actually convicted.[148] A 2006 government report suggests that immigrants face discrimination by law enforcement, which could lead to meaningful differences between those suspected of crimes and those actually convicted.[150] A 2008 report by the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention finds evidence of discrimination towards individuals of foreign descent in the Swedish judicial system.[31] The 2005 report finds that immigrants who entered Sweden during early childhood have lower crime rates than other immigrants.[151] By taking account of socioeconomic factors (gender, age, education and income), the crime rate gap between immigrants and natives decreases.[151]

A 2013 study done by Stockholm University showed that the 2005 study's difference was due to the socioeconomic differences (e.g. family income, growing up in a poor neighborhood) between people born in Sweden and those born abroad.[152][13] The authors furthermore found "that culture is unlikely to be a strong cause of crime among immigrants".[13]

A study published in 1997 attempted to explain the higher than average crime rates among immigrants to Sweden. It found that between 20 and 25 percent of asylum seekers to Sweden had experienced physical torture, and many suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder. Other refugees had witnessed a close relative being killed.[153]

The 2005 study reported that persons from North Africa and Western Asia were over-represented in crime statistics,[148] whereas a 1997 paper additionally found immigrants from Finland, South America, Arab world and Eastern Europe to be over-represented in crime statistics.[153] Studies have found that native-born Swedes with high levels of unemployment are also over-represented in crime statistics.[154]

A 1996 report by the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention determined that between 1985 and 1989 individuals born in Iraq, North Africa (Algeria, Libya, Morocco and Tunisia), Africa (excluding Uganda and the North African countries), other Middle East (Jordan, Palestine, Syria), Iran and Eastern Europe (Romania, Bulgaria) were convicted of rape at rates 20, 23, 17, 9, 10 and 18 greater than individuals born in Sweden respectively.[155] Both the 1996 and 2005 reports have been criticized for using insufficient controls for socioeconomic factors.[13]

A 2013 study found that both first- and second-generation immigrants have a higher rate of suspected offenses than indigenous Swedes.[122] While first-generation immigrants have the highest offender rate, the offenders have the lowest average number of offenses, which indicates that there is a high rate of low-rate offending (many suspected offenders with only one single registered offense). The rate of chronic offending (offenders suspected of several offenses) is higher among indigenous Swedes than first-generation immigrants. Second-generation immigrants have higher rates of chronic offending than first-generation immigrants but lower total offender rates.[122]

United Kingdom

Historically, Irish immigrants to the United Kingdom in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were considered over-represented amongst those appearing in court. Research suggests that policing strategy may have put immigrants at a disadvantage by targeting only the most public forms of crime, while locals were more likely able to engage in the types of crimes that could be conducted behind locked doors.[156] An analysis of historical courtroom records suggests that despite higher rates of arrest, immigrants were not systematically disadvantaged by the British court system in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[157]

On 30 June 2013 there were 10,786 prisoners from 160 different countries in the jails of England and Wales.[158] Poland, Jamaica and the Irish Republic formed the highest percentage of foreign nationals in UK prisons.[158] In total, foreigners represented 13% of the prison population,[158] whereas foreign nationals are 13% of the total population in England and Wales.[159] During the 2000s, there was a 111% increase of foreign nationals in UK prisons.[46] According to one study, "there is little evidence to support the theory that the foreign national prison population continues to grow because foreign nationals are more likely to commit crime than are British citizens or more likely to commit crime of a serious nature".[46] The increase may partly be due to the disproportionate number of convicted for drug offences; crimes associated with illegal immigration (fraud and forgery of government documents, and immigration offenses); ineffective deportation provisions; and a lack of viable options to custody (which affects bail and sentencing decision making).[46]

Research has found no evidence of an average causal impact of immigration on crime.[5][6][46] One study based on evidence from England and Wales in the 2000s found no evidence of an average causal impact of immigration on crime in England and Wales,.[5] No causal impact and no immigrant differences in the likelihood of being arrested were found for London, which saw large immigration changes.[5] A study of two large waves of immigration to the UK (the late 1990s/early 2000s asylum seekers and the post-2004 inflow from EU accession countries) found that the "first wave led to a modest but significant rise in property crime, while the second wave had a small negative impact. There was no effect on violent crime; arrest rates were not different, and changes in crime cannot be ascribed to crimes against immigrants. The findings are consistent with the notion that differences in labor market opportunities of different migrant groups shape their potential impact on crime."[6] A 2013 study found "that crime is significantly lower in those neighborhoods with sizeable immigrant population shares" and that "the crime reducing effect is substantially enhanced if the enclave is composed of immigrants from the same ethnic background."[7] A 2014 study of property crimes based on the Crime and Justice Survey (CJS) of 2003, (a national representative survey where respondents in England and Wales were asked questions regarding their criminal activities), after taking into account the under-reporting of crimes, even found that "immigrants who are located in London and black immigrants are significantly less criminally active than their native counterparts".[2] Another 2014 study found that "areas that have witnessed the greatest percentage of recent immigrants arriving since 2004 have not witnessed higher levels of robbery, violence, or sex offending" but have "experienced higher levels of drug offenses."[160]

It was reported in 2007 that more than one-fifth of solved crimes in London was committed by immigrants. Around a third of all solved, reported sex offences and a half of all solved, reported frauds in the capital were carried out by non-British citizens.[161] A 2008 study found that the crime rate of Eastern European immigrants was the same as that of the indigenous population.[162]

North America

Canada

A 2014 study found that immigration reduced the crime rate in Canada: "new immigrants do not have a significant impact on property crime rates, but as they stay longer, more established immigrants actually decrease property crime rates significantly."[163]

United States

Crime

There is no empirical evidence that either legal or illegal immigration increases crime rate in the United States.[164] Most studies in the U.S. have found lower crime rates among immigrants than among non-immigrants, and that higher concentrations of immigrants are associated with lower crime rates.[1][165][166][167][168][169][170][171][172][173][174][175][176][177][178][179][180][181][182][183][184][185][186][187] These findings contradict popular perceptions that immigration increases crime.[1][188] Some research even suggests that increases in immigration may partly explain the reduction in the U.S. crime rate.[8][189][190][191][192][193][194] A 2017 study suggests that immigration did not play a significant part in lowering the crime rate.[195] A 2005 study showed that immigration to large U.S. metropolitan areas does not increase, and in some cases decreases, crime rates there.[196] A 2009 study found that recent immigration was not associated with homicide in Austin, Texas.[197] The low crime rates of immigrants to the United States despite having lower levels of education, lower levels of income and residing in urban areas (factors that should lead to higher crime rates) may be due to lower rates of antisocial behavior among immigrants.[198] A 2015 study found that Mexican immigration to the United States was associated with an increase in aggravated assaults and a decrease in property crimes.[199] A 2016 study finds no link between immigrant populations and violent crime, although there is a small but significant association between undocumented immigrants and drug-related crime.[200]

A 2018 study found that undocumented immigration to the United States did not increase violent crime.[201] A 2017 study found that "Increased undocumented immigration was significantly associated with reductions in drug arrests, drug overdose deaths, and DUI arrests, net of other factors."[202] Research finds that Secure Communities, an immigration enforcement program which led to a quarter of a million of detentions (when the study was published; November 2014), had no observable impact on the crime rate.[203] A 2015 study found that the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act, which legalized almost 3 million immigrants, led to "decreases in crime of 3–5 percent, primarily due to decline in property crimes, equivalent to 120,000–180,000 fewer violent and property crimes committed each year due to legalization".[24] According to two studies, sanctuary cities—which adopt policies designed to not prosecute people solely for being an illegal alien—have no statistically meaningful effect on crime.[204][205] A 2018 study in the American Economic Journal: Economic Policy found that by restricting the employment opportunities for unauthorized immigrants, the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (IRCA) likely caused an increase in crime.[28][206]

A 2018 paper found no statistically significant evidence that refugees to the United States have an impact on crime rates.[207]

One of the first political analyses in the U.S. of the relationship between immigration and crime was performed in the beginning of the 20th century by the Dillingham Commission, which found a relationship especially for immigrants from non-Northern European countries, resulting in the sweeping 1920s immigration reduction acts, including the Emergency Quota Act of 1921, which favored immigration from northern and western Europe.[208] Recent research is skeptical of the conclusion drawn by the Dillingham Commission. One study finds that "major government commissions on immigration and crime in the early twentieth century relied on evidence that suffered from aggregation bias and the absence of accurate population data, which led them to present partial and sometimes misleading views of the immigrant-native criminality comparison. With improved data and methods, we find that in 1904, prison commitment rates for more serious crimes were quite similar by nativity for all ages except ages 18 and 19, for which the commitment rate for immigrants was higher than for the native-born. By 1930, immigrants were less likely than natives to be committed to prisons at all ages 20 and older, but this advantage disappears when one looks at commitments for violent offenses."[209]

For the early twentieth century, one study found that immigrants had "quite similar" imprisonment rates for major crimes as natives in 1904 but lower for major crimes (except violent offenses; the rate was similar) in 1930.[209] Contemporary commissions used dubious data and interpreted it in questionable ways.[209] A study by Harvard economist Nathan Nunn, Yale economist Nancy Qian and LSE economist Sandra Sequeira found that the Age of Mass Migration (1850–1920) had no long-run effects on crime rates in the United States.[210]

Terrorism

According to a review by the Washington Post fact-checker of the available research and evidence, there is nothing to support President Trump's claim that "the vast majority of individuals convicted of terrorism-related offenses since 9/11 came here from outside of our country."[211] The fact-checker noted that the Government Accountability Office had found that "of the 85 violent extremist incidents that resulted in death since Sept. 12, 2001, 73 percent (62) were committed by far-right-wing violent extremist groups, and 27 percent (23) by radical Islamist violent extremists".[211] A bulletin by the FBI and Department of Homeland Security also warned in May 2017 "that white supremacist groups were “responsible for a lion’s share of violent attacks among domestic extremist groups".[211] According to a report by the New America foundation, of the individuals credibly involved in radical Islamist-inspired activity in the United States since 9/11, the large majority were US-born citizens, not immigrants.[211]

A 2018 paper found no statistically significant evidence that refugee settlements in the United States are linked to terrorism events.[207]

Oceania

Australia

Foreigners are under-represented in the Australian prison population, according to 2010 figures.[27] A 1987 report by the Australian Institute of Criminology noted that studies had consistently found that migrant populations in Australia had lower crime rates than the Australian-born population.[212]

The alleged link between immigration and criminality has been a longstanding meme in Australian history with many of the original immigrants being convicts. During the 1950s and 1960s, the majority of emigrants to the country arrived from Italy and Greece, and were shortly afterwards associated with local crime. This culminated in the "Greek conspiracy case" of the 1970s, when Greek physicians were accused of defrauding the Medibank system. The police were later found to have conducted investigations improperly, and the doctors were eventually cleared of all charges. After the demise of the White Australia policy restricting non-European immigration, the first large settler communities from Asia emerged. This development was accompanied by a moral panic regarding a potential spike in criminal activity by the Triads and similar organizations. In 1978, the erstwhile weekly The National Times also reported on involvement in the local drug trade by Calabrian Italian, Turkish, Lebanese and Chinese dealers.[213]

Discourse surrounding immigrant crime reached a head in the late 1990s. The fatal stabbing of a Korean teenager in Punchbowl in October 1998 followed by a drive-by shooting of the Lakemba police station prompted then New South Wales Premier Bob Carr and NSW Police Commissioner Peter Ryan to blame the incidents on Lebanese gangs. Spurred on by the War on Terror, immigrant identities became increasingly criminalized in the popular Sydney media. By the mid-2000s and the outbreak of the Cronulla riots, sensationalist broadcast and tabloid media representations had reinforced existing stereotypes of immigrant communities as criminal entities and ethnic enclaves as violent and dangerous areas.[213]

The only reliable statistics on immigrant crime in Australia are based on imprisonment rates by place of birth. As of 1999, this data indicated that immigrants from Vietnam (2.7 per 1,000 of population), Lebanon (1.6) and New Zealand (1.6) were over-represented within the national criminal justice system. Compared to the Australian-born (1), immigrants from Italy (0.6), the United Kingdom (0.6), Ireland (0.6) and Greece (0.5) were under-represented.[213]

Victoria Police said in 2012 that Sudanese and Somali immigrants were around five times more likely to commit crimes than other state residents. The rate of offending in the Sudanese community was 7109.1 per 100,000 individuals, whereas it was 6141.8 per 100,000 for Somalis, and 1301.0 per 100,000 for the wider Victoria community. Robbery and assault said to have been the most common types of crime committed by the Sudanese and Somali residents, with assault purported to represent 29.5% and 24.3% of all offences, respectively. The overall proportion of crime in the state said to have been committed by members of the Sudanese community was 0.92 percent, while it was 0.35 percent for Somali residents. People born in Sudan and Somalia are around 0.1 and 0.05 per cent, respectively, of Victoria's population. Journalist Dan Oakes, writing in The Age, noted that individuals arrested and charged might have been falsely claiming to belong to each community.[214] In 2015, Sudanese-born youths were "vastly over-represented" in Victoria Police LEAP data, responsible for 7.44 per cent of alleged home invasions, 5.65 per cent of car thefts and 13.9 per cent of aggravated robberies.[215] A similar overrepresentation occurs in Kenyan-born youths. In January 2018, Acting Chief Commissioner Shane Patton that there was an "issue with overrepresentation by African youth in serious and violent offending as well as public disorder issues".[216]

In the late 2000s, following a series of arrests in Melbourne on terrorism-related charges, Australian security officials expressed concerns of possible attacks by Al-Qaeda-affiliated extremists from North Africa.[217]

In 2010, six applicants brought charges of impropriety against several members of the Victorian Police, the Chief Commissioner of Victoria Police, and the State of Victoria in the Melbourne areas of Flemington and Kensington. The ensuing Haile-Michael v Konstantinidis case alleged various forms of mistreatment by the public officials in violation of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975. In March 2012, an order of discovery was made, whereby established statistician Ian Gordon of the University of Melbourne independently analysed Victorian Police LEAP data from Flemington and North Melbourne (2005–2008). The report concluded that residents from Africa were two and a half times more likely to be subjected to an arbitrary "stop and search" than their representation in the population. Although the justification provided for such disproportionate policing measures was over-representation in local crime statistics, the study found that the same police LEAP data in reality showed that male immigrants from Africa on average committed substantially less crime than male immigrants from other backgrounds. Despite this, the latter alleged male offenders were observed to be 8.5 times more likely not to be the subject of a police "field contact". The case was eventually settled on 18 February 2013, with a landmark agreement that the Victoria Police would publicly review its "field contact" and training processes. The inquiry is expected to help police identify areas where discrimination in the criminal justice system has the potential to or does occur; implement institutional reforms as pre-emptive measures in terms of training, policy and practice; predicate changes on international law enforcement best practices; ammeliorate the local police's interactions with new immigrants and ethnic minorities, as well as with the Aboriginal community; and serve as a benchmark for proper conduct vis-a-vis other police departments throughout the country.[218][219]

The Australian Bureau of Statistics regularly publishes characteristics of those incarcerated including country of birth. The 2014 figures show that in general native-born Australians, New Zealanders, Vietnamese, Lebanese, Sudanese, Iraqi and people from Fiji are responsible for higher share of crime than their share in the population (overrepresented), while people from the UK, the Chinese and people from Philippines are responsible for a lower share (underrepresented).[220]

| Country of Birth | Homicide and related offenses% | All Crime% | National Population% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 76.3 | 81.1 | 69.8 |

| New Zealand | 3.3 | 3.0 | 2.2 |

| Vietnam | 2.1 | 2.3 | 0.9 |

| United Kingdom | 3.2 | 1.8 | 5.1 |

| China | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.5 |

| Lebanon | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.4 |

| Sudan | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.1 |

| Iraq | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| Philippines | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.8 |

| Fiji | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Other | 10.0 | 7.9 | 18.7 |

New Zealand

Foreigners are under-represented in the New Zealand prison population, according to 2010 figures.[27]

Perception of immigrant criminality

Research suggests that people overestimate the relationship between immigration and criminality. A 2016 study of Belgium found that living in an ethnically diverse community lead to a greater fear of crime, unrelated to the actual crime rate.[15] A 2015 study found that the increase in immigration flows into western European countries that took place in the 2000s did "not affect crime victimization, but it is associated with an increase in the fear of crime, the latter being consistently and positively correlated with the natives’ unfavourable attitude toward immigrants."[4] Americans dramatically overestimate the relationship between refugees and terrorism.[16] A 2018 study found that media coverage of immigrants in the United States has a general tendency to emphasize illegality and/or criminal behavior in a way that is inconsistent with actual immigrant demographics.[221]

Political consequences

Research suggests that the perception that there is a positive causal link between immigration and crime leads to greater support for anti-immigration policies or parties.[222][223][224][225][226][227] Research also suggests a vicious cycle of bigotry and immigrant alienation could exacerbate immigrant criminality and bigotry. For instance, University of California, San Diego political scientist Claire Adida, Stanford University political scientist David Laitin and Sorbonne University economist Marie-Anne Valfort argue "fear-based policies that target groups of people according to their religion or region of origin are counter-productive. Our own research, which explains the failed integration of Muslim immigrants in France, suggests that such policies can feed into a vicious cycle that damages national security. French Islamophobia—a response to cultural difference—has encouraged Muslim immigrants to withdraw from French society, which then feeds back into French Islamophobia, thus further exacerbating Muslims’ alienation, and so on. Indeed, the failure of French security in 2015 was likely due to police tactics that intimidated rather than welcomed the children of immigrants—an approach that makes it hard to obtain crucial information from community members about potential threats."[228]

A study of the long-run effects of the 9/11 terrorist attacks found that the post-9/11 increase in hate crimes against Muslims decreased assimilation by Muslim immigrants.[229] Controlling for relevant factors, the authors found that "Muslim immigrants living in states with the sharpest increase in hate crimes also exhibit: greater chances of marrying within their own ethnic group; higher fertility; lower female labour force participation; and lower English proficiency."[229]

States that experience terrorist acts on their own soil or against their own citizens are more likely to adopt stricter restrictions on asylum recognition.[230] Individuals who believe that African Americans and Hispanics are more prone to violence are more likely to support capital punishment.[231]

The Dillingham Commission singled out immigrants from Southern Europe for their involvement in violent crime (even though the data did not support its conclusions).[209] The Commission's overall findings provided the rationale for sweeping 1920s immigration reduction acts, including the Emergency Quota Act of 1921, which favored immigration from northern and western Europe by restricting the annual number of immigrants from any given country to 3 percent of the total number of people from that country living in the United States in 1910. The movement for immigration restriction that the Dillingham Commission helped to stimulate culminated in the National Origins Formula, part of the Immigration Act of 1924, which capped national immigration at 150,000 annually and completely barred immigration from Asia.[232]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "The Integration of Immigrants into American Society". National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2015. doi:10.17226/21746.

Americans have long believed that immigrants are more likely than natives to commit crimes and that rising immigration leads to rising crime... This belief is remarkably resilient to the contrary evidence that immigrants are in fact much less likely than natives to commit crimes.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Papadopoulos, Georgios (2014-07-02). "Immigration status and property crime: an application of estimators for underreported outcomes". IZA Journal of Migration. 3 (1): 12. doi:10.1186/2193-9039-3-12. ISSN 2193-9039.

- 1 2 3 Bianchi, Milo; Buonanno, Paolo; Pinotti, Paolo (2012-12-01). "Do Immigrants Cause Crime?". Journal of the European Economic Association. 10 (6): 1318–1347. doi:10.1111/j.1542-4774.2012.01085.x. ISSN 1542-4774.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Nunziata, Luca (2015-03-04). "Immigration and crime: evidence from victimization data". Journal of Population Economics. 28 (3): 697–736. doi:10.1007/s00148-015-0543-2. ISSN 0933-1433.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jaitman, Laura; Machin, Stephen (2013-10-25). "Crime and immigration: new evidence from England and Wales". IZA Journal of Migration. 2 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1186/2193-9039-2-19. ISSN 2193-9039.

- 1 2 3 4 Bell, Brian; Fasani, Francesco; Machin, Stephen (2012-10-10). "Crime and Immigration: Evidence from Large Immigrant Waves". Review of Economics and Statistics. 95 (4): 1278–1290. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00337. ISSN 0034-6535.

- 1 2 3 Bell, Brian; Machin, Stephen (2013-02-01). "Immigrant Enclaves and Crime". Journal of Regional Science. 53 (1): 118–141. doi:10.1111/jors.12003. ISSN 1467-9787.

- 1 2 3 Wadsworth, Tim (2010-06-01). "Is Immigration Responsible for the Crime Drop? An Assessment of the Influence of Immigration on Changes in Violent Crime Between 1990 and 2000". Social Science Quarterly. 91 (2): 531–553. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6237.2010.00706.x. ISSN 1540-6237.

- 1 2 Lee, Matthew T.; Martinez Jr., Ramiro (2009). "Immigration reduces crime: an emerging scholarly consensus". Immigration, Crime and Justice. Emerald Group Publishing. pp. 3–16. ISBN 9781848554382.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bell, Brian; Oxford, University of; UK (2014). "Crime and immigration". IZA World of Labor. doi:10.15185/izawol.33.

- ↑ Ousey, Graham C.; Kubrin, Charis E. (2018). "Immigration and Crime: Assessing a Contentious Issue". Annual Review of Criminology. 1 (1): null. doi:10.1146/annurev-criminol-032317-092026.

- 1 2 3 Crocitti, Stefania. Immigration, Crime, and Criminalization in Italy – Oxford Handbooks. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199859016.013.029.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hällsten, Martin; Szulkin, Ryszard; Sarnecki, Jerzy (2013-05-01). "Crime as a Price of Inequality? The Gap in Registered Crime between Childhood Immigrants, Children of Immigrants and Children of Native Swedes". British Journal of Criminology. 53 (3): 456–481. doi:10.1093/bjc/azt005. ISSN 0007-0955.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Colombo, Asher (2013-11-01). "Foreigners and immigrants in Italy's penal and administrative detention systems". European Journal of Criminology. 10 (6): 746–759. doi:10.1177/1477370813495128. ISSN 1477-3708.

- 1 2 Hooghe, Marc; de Vroome, Thomas (2016-01-01). "The relation between ethnic diversity and fear of crime: An analysis of police records and survey data in Belgian communities". International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 50: 66–75. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.11.002.

- 1 2 "America's puzzling moral ambivalence about Middle East refugees | Brookings Institution". Brookings. 2016-06-28. Retrieved 2017-01-26.

- 1 2 3 "Centre for Economic Policy Research". cepr.org. Retrieved 2017-08-15.

- 1 2 3 Bove, Vincenzo; Böhmelt, Tobias (2016-02-11). "Does Immigration Induce Terrorism?". The Journal of Politics. 78 (2). doi:10.1086/684679. ISSN 0022-3816.

- ↑ Buonanno, Paolo; Drago, Francesco; Galbiati, Roberto; Zanella, Giulio (2011-07-01). "Crime in Europe and the United States: dissecting the 'reversal of misfortunes'". Economic Policy. 26 (67): 347–385. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0327.2011.00267.x. ISSN 0266-4658.

- ↑ Piopiunik, Marc; Ruhose, Jens (2015-04-06). "Immigration, Regional Conditions, and Crime: Evidence from an Allocation Policy in Germany". Rochester, NY. SSRN 2589824.

- ↑ "Understanding the Role of Immigrants' Legal Status: Evidence from Policy Experiments". www.iza.org. Retrieved 2016-01-29.

- 1 2 3 Piopiunik, Marc; Ruhose, Jens (2017). "Immigration, regional conditions, and crime: evidence from an allocation policy in Germany". European Economic Review. 92: 258. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2016.12.004.

- 1 2 3 Mastrobuoni, Giovanni; Pinotti, Paolo (2015). "Legal Status and the Criminal Activity of Immigrants". American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 7 (2): 175–206. doi:10.1257/app.20140039.

- 1 2 Baker, Scott R. (2015). "Effects of Immigrant Legalization on Crime". American Economic Review. 105 (5): 210–213. doi:10.1257/aer.p20151041.

- ↑ Pinotti, Paolo (2014-10-01). "Clicking on Heaven's Door: The Effect of Immigrant Legalization on Crime". Rochester, NY. SSRN 2426502.

- ↑ Fasani, Francesco (2014-01-01). "Understanding the Role of Immigrants' Legal Status: Evidence from Policy Experiments". Centre for Research and Analysis of Migration (CReAM), Department of Economics, University College London.

- 1 2 3 4 "Refugees and Economic Migrants: Facts, policies and challenges". VoxEU.org. 2016-10-31. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- 1 2 Matthew, Freedman,; Emily, Owens,; Sarah, Bohn,. "Immigration, Employment Opportunities, and Criminal Behavior". American Economic Journal: Economic Policy. doi:10.1257/pol.20150165&&from=f (inactive 2018-03-21). ISSN 1945-7731.

- 1 2 3 "Indvandrere i Danmark" [Immigrants in Denmark] (in Danish). Statistics Denmark. 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Damm, Anna Piil; Dustmann, Christian (2014). "Does Growing Up in a High Crime Neighborhood Affect Youth Criminal Behavior?". American Economic Review. 104 (6): 1806–1832. doi:10.1257/aer.104.6.1806.

- 1 2 3 "Diskriminering i rättsprocessen - Brå". www.bra.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 2016-01-26.

- ↑ Warren, Patricia Y.; Tomaskovic-Devey, Donald (2009-05-01). "Racial profiling and searches: Did the politics of racial profiling change police behavior?*". Criminology & Public Policy. 8 (2): 343–369. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9133.2009.00556.x. ISSN 1745-9133.

- ↑ Statistics on Race and the Criminal Justice System 2008/09, p. 8, 22

- ↑ West, Jeremy (February 2018). "Racial Bias in Police Investigations" (PDF). Working Paper.

- ↑ Parmar, Alpa. Ethnicities, Racism, and Crime in England and Wales – Oxford Handbooks. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199859016.013.014.

- ↑ Donohue III, John J.; Levitt, Steven D. (2001-01-01). "The Impact of Race on Policing and Arrests". The Journal of Law & Economics. 44 (2): 367–394. doi:10.1086/322810. JSTOR 10.1086/322810.

- ↑ Abrams, David S.; Bertrand, Marianne; Mullainathan, Sendhil (2012-06-01). "Do Judges Vary in Their Treatment of Race?". The Journal of Legal Studies. 41 (2): 347–383. doi:10.1086/666006. ISSN 0047-2530.

- ↑ Mustard, David B. (2001-04-01). "Racial, Ethnic, and Gender Disparities in Sentencing: Evidence from the U.S. Federal Courts". The Journal of Law and Economics. 44 (1): 285–314. doi:10.1086/320276. ISSN 0022-2186.

- ↑ Anwar, Shamena; Bayer, Patrick; Hjalmarsson, Randi (2012-05-01). "The Impact of Jury Race in Criminal Trials". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 127 (2): 1017–1055. doi:10.1093/qje/qjs014. ISSN 0033-5533.

- ↑ Daudistel, Howard C.; Hosch, Harmon M.; Holmes, Malcolm D.; Graves, Joseph B. (1999-02-01). "Effects of Defendant Ethnicity on Juries' Dispositions of Felony Cases". Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 29 (2): 317–336. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1999.tb01389.x. ISSN 1559-1816.

- ↑ Holmberg, Lars; Kyvsgaard, Britta (2011). "Are Immigrants and Their Descendants Discriminated against in the Danish Criminal Justice System". Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention. 4 (2): 125–142. doi:10.1080/14043850310020027.

- ↑ Roché, Sebastian; Gordon, Mirta B.; Depuiset, Marie-Aude. Case Study – Oxford Handbooks. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199859016.013.030.

- ↑ Depew, Briggs; Eren, Ozkan; Mocan, Naci (2017). "Judges, Juveniles, and In-Group Bias". Journal of Law and Economics. 60 (2): 209–239. doi:10.1086/693822.

- ↑ Light, Michael T. (2016-03-01). "The Punishment Consequences of Lacking National Membership in Germany, 1998–2010". Social Forces. 94 (3): 1385–1408. doi:10.1093/sf/sov084. ISSN 0037-7732.

- ↑ Wermink, Hilde; Johnson, Brian D.; Nieuwbeerta, Paul; Keijser, Jan W. de (2015-11-01). "Expanding the scope of sentencing research: Determinants of juvenile and adult punishment in the Netherlands". European Journal of Criminology. 12 (6): 739–768. doi:10.1177/1477370815597253. ISSN 1477-3708.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Banks, James (2011-05-01). "Foreign National Prisoners in the UK: Explanations and Implications". The Howard Journal of Criminal Justice. 50 (2): 184–198. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2311.2010.00655.x. ISSN 1468-2311.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Immigration policy and crime" (PDF). 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-02-02.

- ↑ Dahlbäck, Olof (2009). "Diskrimineras invandrarna i anmälningar av brott?" (PDF).

- ↑ "Crimes of Mobility: Criminal Law and the Regulation of Immigration (Hardback) - Routledge". Routledge.com. Retrieved 2016-03-04.

- ↑ Bosworth, Mary (2011-05-01). "Deportation, Detention and Foreign National Prisoners in England and Wales". SSRN Electronic Journal. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1852191. SSRN 1852191.

- ↑ Feltes, Thomas; List, Katrin; Bertamini, Maximilian (2018), "More Refugees, More Offenders, More Crime? Critical Comments with Data from Germany", Refugees and Migrants in Law and Policy, Springer International Publishing, pp. 599–624, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-72159-0_26, ISBN 9783319721583, retrieved 2018-10-05

- ↑ "Immigration and Terrorism". Archived from the original on

|archive-url=requires|archive-date=(help). - 1 2 3 Dreher, Axel; Gassebner, Martin; Schaudt, Paul (2017-08-12). "Migration and terror". VoxEU.org. Retrieved 2017-08-15.

- ↑ Dreher, Axel; Gassebner, Martin; Schaudt, Paul (2017-09-01). "The Effect of Migration on Terror – Made at Home or Imported from Abroad?". Rochester, NY. SSRN 2976273.

- ↑ Roy, Olivier (2017-04-13). "Who are the new jihadis? | Olivier Roy | The long read". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2018-09-24.

- ↑ "Why Trump's Policies Will Increase Terrorism – and Why Trump Might Benefit as a Result". Lawfare. 2017-01-30. Retrieved 2017-08-15.

- ↑ "'That Ignoramus': 2 French Scholars of Radical Islam Turn Bitter Rivals". Retrieved 2018-07-19.

“There is no proof that shows the young men go from Salafism to terrorism,” Mr. Roy said, pointing out that the planner of the Paris attacks in November, Abdelhamid Abaaoud, ate McDonald’s, which is not halal. “None of the terrorists were Salafists.”

- ↑ Lerner, Davide (2017-06-14). "London Gave Shelter to Radical Islam and Now It's Paying the Price, French Terrorism Expert Says". Haaretz. Retrieved 2018-06-09.

- ↑ Yamamoto, Ryoko; Johnson, David. Convergence of Control – Oxford Handbooks. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199859016.013.012.

- ↑ Wudunn, Sheryl (March 12, 1997). "Japan Worries About a Trend: Crime by Chinese". The New York Times. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- 1 2 Ozden, Caglar; Testaverde, Mauro; Wagner, Mathis (2018). "How and Why Does Immigration Affect Crime? Evidence from Malaysia". The World Bank Economic Review. 32: 183. doi:10.1093/wber/lhx010.

- ↑ Indvandrere i Danmark 2016. [Statistics Denmark]]. 2016. pp. 81, 84. ISBN 978-87-501-2236-4.

- 1 2 3 "Indvandrere i Danmark 2015". Statistics Denmark. 2015.

- ↑ Slotwinski, Michaela; Stutzer, Alois; Gorinas, Cédric (2017-02-27). "Democratic Involvement and Immigrants' Compliance with the Law". Rochester, NY. SSRN 2923633.

- ↑ "GRAFIK Indvandrede og efterkommere halter efter etniske danskere". DR (in Danish). Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- ↑ Salmi, Venla; Kivivuori, Janne; Aaltonen, Mikko (2015-11-01). "Correlates of immigrant youth crime in Finland". European Journal of Criminology. 12 (6): 681–699. doi:10.1177/1477370815587768. ISSN 1477-3708.

- ↑ "Finland 2013 Crime and Safety Report". www.osac.gov. Retrieved 2016-06-09.

- ↑ "Rikollisuustilanne 2014 – rikollisuuskehitys tilastojen ja tutkimusten valossa" (PDF). Helsingin yliopisto – Kriminologian ja oikeuspolitiikan instituutti.

- ↑ "Immigration to Finland". www.intermin.fi. Ministry of the Interior. Retrieved 2016-06-09.

- ↑ "Number of persons speaking national languages as their native language went down for the second year in a row" (PDF).

- ↑ "Foreigners figure high in rape statistics". Archived from the original on 2012-03-14.

When the victims file their accusations, as many as 17% of the women involved believed the rapist to be of foreign extraction. This is a pretty huge figure, given that there are only some 85,000 foreigners living in Finland, or just 1.65% of the population.

- 1 2 3 4 "Finskor offer för 80% av asylinvandrares sexbrott – hälften av dem flickor under 18". Ålands Nyheter. 9 May 2018. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- ↑ Aoki, Yu; Todo, Yasuyuki (2009-10-01). "Are immigrants more likely to commit crimes? Evidence from France". Applied Economics Letters. 16 (15): 1537–1541. doi:10.1080/13504850701578892. ISSN 1350-4851.

- ↑ Khosrokhavar, Farhad (5 July 2016). "Anti-Semitism of the Muslims in France: the case of the prisoners" (PDF). Stanford University. Stanford University. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ↑ Khosrokhavar, Farhad (2004). L’islam dans les prisons. Paris: Editions Balland. ISBN 9782715814936.

- ↑ "60% des détenus français sont musulmans ?". Franceinfo (in French). 2015-01-25. Retrieved 2017-08-27.

- 1 2 "BKA - Bundeslagebilder Organisierte Kriminalität - Bundeslagebild Organisierte Kriminalität 2017". www.bka.de (in German). p. 13. Retrieved 2018-08-11.