Immigration and crime in Germany

Immigration and crime in Germany refers to crimes committed against and by immigrants in Germany.

Crimes by foreigner has been a longstanding theme in public debates in Germany.[1]

"Guest worker" era in the 1950s-1980s

The Ausländergesetz (Deutschland) (Foreigners Act) of 1965 attempted to control immigration to West Germany.[2]

During the 1950s and 1960s, a group known as Gastarbeiter participated in an organised immigration programme to the former West Germany because of labour shortages in the country. The former East Germany also had labour shortages but their "guest worker" programme tended to encourage immigration from other socialist and communist countries. Many former "guest workers" became German citizens. The first generation of "guest workers" did not have an elevated crime rate, second- and third-generation immigrants studied in the 1970s and 1980s had higher crime rates than their German contemporaries who were not from an immigrant background.[3]

A 1991 Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich study covering the preceding two decades found that immigrants with a strongly different cultural background compared to German culture had particularly high crime rates. Under the guest worker programme, Turks and Yugoslavs had far higher crime rates than Spaniards and Portugese, while the highest crime rates were recorded among individuals from third world countries. For third world countries, the immigrants were first generation.[4]

Criminal activity by immigrants since the 1990s

Studies in the 1990s showed a correlation between immigrant populations in Germany and crime.[5]

The 1999 bill making naturalisation of immigrants contingent upon a written declaration that the applicant was loyal to the Constitution, competent in German language, not dependent on welfare and had no criminal record was the first piece of legislation to mention crime in relation to immigration.[6][7]

Studies in the early 2000s tended to show little correlation between migrants and crime in Germany.[8][9]

From the start of 2015 to the end of 2017, 1356600 asylum seekers were registered in total.[10] According to a 2018 study by German criminologists, the crime rate of non-Germans between the ages of 16 and 30 is within the same range as that of Germans.[11]

In May 2016, U.S. fact-checker Politifact noted that 2016 data suggest that the crime rate of the average refugee is lower than that of the average German.[12] In 2018 the interior ministry's report "Criminality in context with immigration" (German: Kriminalität im Kontext von Zuwanderung) [10] for the first time summarized and singled out all people who entered Germany via the asylum system. The group called "immigrants" includes all asylum seekers, tolerated people, "unauthorized residents" and all those entitled to protection (subsidiary protected, contingent refugees and refugees under the Geneva Convention and asylum). The group represented roughly 2 percent of the German population by end of 2017[13], but was suspected of comitting 8.5 percent of crimes (violations off the german alien law are not included). The numbers suggest that the differences could at least to some extent have to do with the fact that the refugees are younger and more often male than the average German. The statistics show that the asylum-group is highly overrepresented for some types of crime. They account for 14.3 percent of all suspects in crimes against life (which include murder, manslaughter and involuntary manslaughter), 12.2 percent of sexual offences, 11.4 percent of thefts and 9.7 percent of body injuries The report also shows differences between the origin of migrants. Syrians are underrepresented as suspects, whereas citizens from most african countries, especially northern africans are strongly overerrepresented. Afghans and Pakistani are particularly overerrepresented at sexual offenses.[10][13]

From 2015 to 2016, the number of suspected crimes by refugees, asylum-seekers and illegal immigrants increased by 50 percent.[14] The figures showed that most of the suspected crimes were by repeat offenders, and that 1 percent of migrants accounted for 40 percent of total migrant crimes.[14] From 2016 to 2017, the number of crimes committed by refugees, asylum-seekers and illegal immigrants in Germany decreased by 40 percent, which was mostly caused by significantly less violations off the alien law, because far fewer asylum seekers entered the county in this year.[15]

The first comprehensive study of the social effects of the one million refugees going to Germany found that it caused "very small increases in crime in particular with respect to drug offenses and fare-dodging."[16][17] A report released by the German Federal Office of Criminal Investigation in November 2015 found that over the period January–September 2015, the crime rate of refugees was the same as that of native Germans.[18] According to Deutsche Welle, the report "concluded that the majority of crimes committed by refugees (67 percent) consisted of theft, robbery and fraud. Sex crimes made for less than 1 percent of all crimes committed by refugees, while homicide registered the smallest fraction at 0,1 percent."[18] According to the conservative newspaper Die Welt's description of the report, the most common crime committed by refugees was not paying fares on public transportation.[19] According to Deutsche Welle's reporting in February 2016 of a report by the German Federal Office of Criminal Investigation, the number of crimes committed by refugees did not rise in proportion to the number of refugees between 2014-2015.[20] According to Deutsche Welle, "between 2014 and 2015, the number of crimes committed by refugees increased by 79 percent. Over the same period, the number of refugees in Germany increased by 440 percent."[20]

DW reported in 2006 that in Berlin, young male immigrants are three times more likely to commit violent crimes than their German peers.[21] Whereas the Gastarbeiter in the 50s and 60s did not have an elevated crime rate, second- and third-generation of immigrants had significantly higher crime rates.[22]

A study in the European Economic Review found that the immigration of more than 3 million people of German descent to Germany after the collapse of the Soviet Union led to a significant increase in crime.[23] The effects were strongest in regions with high unemployment, high preexisting crime levels or large shares of foreigners.[23]

The independent reported that in 2017 crime in Germany was at its lowest for 30 years, and that crimes by non-Germans had fallen by 23% to just over 700,000.[24]

Organised crime

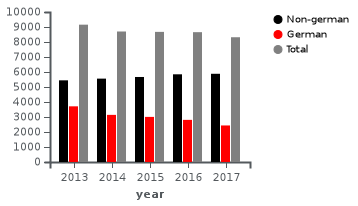

| Number of suspects in organized crime in Germany | |

| |

| Source: BKA[25] | |

In 2017, as in previous years, German citizens constituted the largest group of suspects in organised crime trials. The proportion of non-German citizen suspects increased from 67.5% to 70.7% while the proportion of German citizens decreased correspondingly. For the German citizens, 14.9% had a different citizenship at birth.[25]

For several types of crime and drug crime in particular, organised crime gangs were dominated by people from countries with high rates of immigration to Germany.[10] In 2017, the most common nationality of foreign organized crime gangs was Albanian with 21 gangs, the great majority of which were active in drug trafficking.[10] In 2017 there were 13 identified Serbian organized crime gangs, active in drug crime, property crime and violent crime.[10] In 2017 there were 12 Kosovar gangs, active in property crime, drug trade and forgeries.[10] Syrian gangs were active in drug trade and drug smuggling.[10]

In 2017, 16 Nigerian crime gangs were active in illegal immigration (German: Schleuserkriminalität) drug crime and other offenses in the night life scene.[26]

In an opinion piece in the Sueddeutsche Zeitung in September 2018, the political scientist Ralph Ghadban argued that federal authorities had refused to recognise the specific problem of organized crime gangs based on family ties and ethnicity (German: Clankriminalität), subsuming it under "organised crime" and that, encouraged by the success of the Arab clans, families from other ethnic groups, including Chechens, Albanians, and Kosovars were developing similar structures. According to Ghadban, these structures present a threat to liberal, individualised societies because they hinder integration. A modern society, he says, only functions when people voluntarily follow its rules, but clan members consider themselves members of a family rather than citizens of a country, and do not submit to the rule of law, regarding individuals who do so as weak and unprotected.[27]

By region

Baden-Württemberg

Knife attacks strongly rose in the state Baden-Württemberg from 3,858 in 2013 to 4,874 in 2017. The number of suspects of knife attacks who were asylum seekers rose from 220 in 2013 to 898 in 2017. As a reaction to these figures, Interior Minister Thomas Strobl (CDU) asked other German federal states to record knife attacks in their crime statistics.[28]

Bavaria

The state Bavaria has registered the number of crimes with at least one foreign suspect since 2009. In 2009 there were 5506 such cases, there was an increased to 13 203 crimes in 2014 and in 2016 there were 36 027 such cases. The official Bavarian indirectly attributes the increase to the migration policy of the federal government.[13]

Berlin

DW reported in 2006 that in Berlin, young male immigrants are three times more likely to commit violent crimes than their German peers.[29]

In the 90s, police in the Berlin district Neukölln raised concerns about a dozen lebanese-kurdish families, but their concerns were rebutted with the families being war refugees and they would some day return to their home countries. In 2011, of the 25 Arab extended families (German: Großfamilien) in Berlin, six were heavily involved in crime. According to a migration official in Neukölln, of the 204 young repeat offenders, half had an Arab name.[30] This later turned out not to be the case. In Berlin, clans of Arab descent have organised parallel societies in Berlin and Bremen where they sustain themselves by crime.[31][32][33][34] In Berlin, 20 extended families with each having up to 500 members are established according to estimates of the police, but not all family members are involved in crime. According to the Landeskriminalamt, a third of a all court proceedings against organized crime concerns members of the clans. About half of the clan suspects had a German passport.[34] In July 2018, 77 real estate properties to a value of 10 millon euro were confiscated from Arab clan "R" by the authorities as they had been purchased with funds earned by crime.[35]

In a sample of the 3930 prison population of Berlin 31 March 2018, 51% had no German citizenship. Of the individuals in pre-trial detention facilities, 75% had foreign nationality. Individuals from 90 different countries serve sentences in Berlin prisons.[36]

Bremen

According to the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, of the 2600 "Mhallami-Kurds" (German: Mhallamiye-Kurden) 1100 have been indicted for crime in court. This term makes it clear that the controversial Arab families originated in the Kurdish areas of Turkey.[30] The families are noted for their readiness to use violence and attendands threats thereof, which according to police goes beyond mere crime, but serves as a display of power to the surroundings.[30]

Duisburg

By 2018, crime by ethnically diverse groups (German: Clankriminalität) had taken on proportions which necessitated a response from authorities so two prosecutors were tasked with counter-acting such crime. According to Horst Bien, chief of the public prosecutor's office there are about 70 extended families (German: Großfamilien) of turkish, kurdish and arab descent with about 2800 members. All members of the 70 clans are not involved, predominently male members are prevalent in judicial proceedings. Commonly the charges involve grievous bodily harm, robbery, extortion and narcotics trade.[37]

Hamburg

Hamburg police reported criminal proceedings being opened against 38,000 people in the first six months of 2016, of which 16,600 persons or 43% of the defendants had no German papers. This represents a rise from 41% of defendants without German papers in 2015.[38] The number of foreign criminals increased by 16.7% over 2015; 9.5% of the suspects were refugees. The figures did not include crimes against the German alien law. Foreign crime gangs were named as one reason for the rising figures. Refugees committed mostly pickpocketing, representing 30.6% of all suspects. 27.5% of suspects in drug dealing also arrived as refugees. Another common crime committed by refugees was bodily injury, with 1,014 cases reported, mostly in the asylum centers.[38]

Saxony

On 5 December 2016, the Interior Minister of Saxony, Markus Ulbig, released figures about foreign criminals in the state from January to September. A large proportion of them came from North Africa; 664 North Africans were responsible for 36% of all 14,043 crimes committed by immigrants.[39] By the end of October 2016, 31,000 asylum seekers resided in Saxony.[40] In total, in Saxony 7,579 immigrants were perpetrators, counting only solved cases. 5,288 of the crimes were theft and robbery; 2,214 were bodily injury; and 169 were sexual assaults, representing a rise from 25 recorded cases in 2013.[39] A 2018 study showed that in Lower Saxony, chosen by the researches because of its typicality, reported violent crime increased by 10.4% in 2015 and 2016, with 92.1% of the increase was attributable to migrants.[41]

Blade weapon crimes

According to the police union, the German government does not keep a record of knife and blade related crimes as a distinct type of crime. The German Police Trade Union (DPoIG) has highlighted the issue and has sought that carrying a knife—which its members highlights involve "noticeably" young migrants — be prosecuted under attempted murder provisions in Germany, and urged government to compile statistics nationwide on knife incidents.[42]

A series of prominent incidents involving knives led to the issue becoming a political issue. These include incidents where an attacker murdered their partner such as the 2017 Kandel stabbing attack, the Reutlingen knife attack, the 2018 Hamburg stabbing attack where a 33 year old from Niger (who arrived to Germany in 2013) stabbed and killed his ex-wife and daughter, as well as incidents like the 2018 Burgwedel stabbing where a 17 year old Syrian who had arrived to Germany in 2003 stabbed and injured a woman following a brawl between two youths in a supermarket, the 2018 Flensburg stabbing incident where a 24 year old Eritrean refugee who arrived in Germany in September 2015 was shot and killed after stabbing a police woman with a kitchen knife, and the 2017 Siegaue rape case where a 31 year old Ghanaian used a Machete in an attack where a victim was raped.[43][44][45][46][47]

Crimes against immigrants since the 1990s

The long history of Turkish immigration to Germany resulted in Turkish immigrant families becoming one of the largest ethnic minorities in Germany,[48] estimated at between 2.5 and 4 million.[49] Around a third of these still hold Turkish citizenship.[50] On 27 October 1991, Mete Ekşi (de), a 19-year-old student from Kreuzberg, was attacked by three neo-Nazi German brothers. Ekşi's funeral in November 1991 was attended by 5,000 people.[51] Aslı Bayram's father was murdered in 1994 by a neo-Nazi and Bayram herself was wounded in the attack.[52]

In 1993, an arson attack against a Turkish household in the town of Solingen in North Rhine-Westphalia caused the deaths of five people. Ahead of a commemorative event in 2018, 25 years after the event, Turkey's Foreign Office noted that "racism, xenophobia and Islamophobia are on the rise" in Germany and a representative of the family who were attacked called for reconciliation. A spokesman for anti-right demonstrators at the commemoration said, "When you look at how the mood was back then and how it is turning again now, I believe it's important to rally in the streets and to speak out against it."[53]

According to a 2016 study, there were 1,645 instances of anti-refugee violence and social unrest in Germany during the years 2014 and 2015.[54]

According to the German Federal Criminal Office, there were 797 attacks against residences of refugees or migrants from January to October 2016. 740 attacks had a right-wing background, which also couldn't be ruled out in 57 further cases. Of these, 320 cases of property damage were recorded, in 180 cases propaganda material was dispersed and in 137 cases violence was used. In addition, 61 incidents of arson as well as 10 violations of the Explosives Law, 4 of them in front of a residence of refugees, were registered. According to Der Tagesspiegel, there were also 11 cases of attempted murder or homicide. In 2015, there had been 1,029 attacks against refugee residences, following 199 in 2014.[55] Germany's interior ministry stated that 560 people, including 43 children, had been injured in such attacks during 2016.[56]

A 2017 study found that "the strength of right-wing parties in a district considerably boosts the probability of attacks on refugees in that area."[57]

A 2018 paper found that xenophobic violence during the 1990s in Germany reduced the integration and well-being of immigrants.[58]

Vigilantism and anti-immigrant protests

Vigilantism against immigrants is considered to have become more widespread after the sexual assaults by migrants in Cologne and other German cities on New Year's Eve 2015. In January 2016 a mob attacked a group of Pakistanis in Cologne, and at Bautzen in February, an arson attack on a hostel for asylum seekers took place[59] In February 2018, in Heilbronn, a 70-year-old man knifed three immigrants while drunk, in a protest "about the current refugee policy".[60] A perceived increase in attacks on immigrants led to Chancellor Angela Merkel condemning anti-immigrant "vigilante" groups following the Chemnitz incident.[61]

Female Genital Mutilation

FGM is banned in Germany.[62] According to women's right organisation Terre des Femmes in 2014, there were 25,000 victims in Germany and a further 2,500 are under threat of becoming mutilated.[63] In 2017, Terre des Femmes estimated that 58000 were victims of FGM with a further 13000 being at risk of having the procedure done to them.[62] The latter figure was due to an increased influx of migrants from Somalia, Eritrea and Iraq.[62] In 2018, the estimate had increased to 65000. A further 15500 were at risk of having the mutilation done to them which represented an increase of 17% on the previous year.[64]

Political impact

According to criminologist Simon Cottee, sociologist Stanley Cohen analyzed fear of immigrant crime among Germans and other contemporary Europeans in the 1960s as a form of moral panic.[65]

Four violent crimes committed during the week of 18 July 2016–three of them, the Reutlingen knife attack, 2016 Ansbach bombing, Würzburg train attack, were committed by asylum seekers–created significant political pressure for changes in the Angela Merkel administration policy of welcoming refugees.[66] The Wall Street Journal reported that two notorious crimes committed by asylum seekers in consecutive weeks in December 2016 had added fuel to debates on immigration and surveillance in Germany.[67] The Siegaue rape case as well as the 2017 Kandel stabbing attack, in which a migrant who had been denied refugee status but who had not been deported killed his 16-year-old girlfriend, intensified the discussion about admitting migrants.[68]

The 2018 murder of 14-year-old Susanna in Wiesbaden sparked a debate on how the Iraqi migrant and his family were able to leave the country using fake identities along with how the 20-year-old suspect Ali Bashar had been able to stay in Germany after his asylum application was rejected.[69][70]

See also

References

- ↑ Challenging multiculturalism : European models of diversity. Taras, Ray, 1946-. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. 2013. p. 172. ISBN 9780748664597. OCLC 827947231.

- ↑ Jenny Gesley (March 2017). "Germany: The Development of Migration and Citizenship Law in Postwar Germany". The Law Library of Congress. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ↑ Dünkel, Frieder. "Migration and ethnic minorities in Germany: impacts on youth crime, juvenile justice and youth imprisonment" (PDF). University of Greifswald. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 January 2016.

- ↑ Heinz, Schöch,; Michael, Gebauer, (1991-01-01). "Ausländerkriminalität in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland (PDF download)". epub.ub.uni-muenchen.de (in German). Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München. p. 56. doi:10.5282/ubm/epub.6554. Retrieved 2018-10-13.

- ↑ Chapin, Wesley D. "Ausländer Raus? The Empirical Relationship between Immigration and Crime in Germany." Social Science Quarterly 78, no. 2 (1997): 543-58. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42864353.

- ↑ "Einbuergerungsbewerber muessen verfassungstreu sein". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German): 1. 13 January 1999.

- ↑ Christian Joppke (1999). "The Domestic Legal Sources of Immigrant Rights: The United States, Germany, and the European Union" (PDF). European University Institute, Florence (EUI Working Paper SPS No. 99/3). Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ↑ Horn, Heather (27 April 2016). "Where Does Fear of Refugees Come From?". The Atlantic. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- ↑ "Report: refugees have not increased crime rate in Germany". Deutsche Welle. 13 November 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Kriminalität im Kontext von Zuwanderung - Bundeslagebild 2017". BKA. 2018. p. 55, 61.

- ↑ Feltes, Thomas; List, Katrin; Bertamini, Maximilian (2018), "More Refugees, More Offenders, More Crime? Critical Comments with Data from Germany", Refugees and Migrants in Law and Policy, Springer International Publishing, pp. 599–624, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-72159-0_26, ISBN 9783319721583, retrieved 2018-10-05

- ↑ "Donald Trump says Germany now riddled with crime thanks to refugees". @politifact. Retrieved 2016-05-12.

- 1 2 3 "Zuwanderer in einigen Kriminalitätsfeldern besonders auffällig". Die Welt.

- 1 2 https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/04/25/migrant-crime-germany-rises-50-per-cent-new-figures-show/

- ↑ "Kriminalität geht in Deutschland so stark zurück wie seit 1993 nicht". Die Welt.

- ↑ Mohdin, Aamna. "What effect did the record influx of refugees have on jobs and crime in Germany? Not much". Quartz. Retrieved 2017-02-03.

- ↑ Gehrsitz, Markus; Ungerer, Martin (2017-01-01). "Jobs, Crime, and Votes: A Short-Run Evaluation of the Refugee Crisis in Germany". Rochester, NY. SSRN 2903116.

- 1 2 (www.dw.com), Deutsche Welle. "Report: refugees have not increased crime rate in Germany | News | DW.COM | 13.11.2015". DW.COM. Retrieved 2016-01-26.

- ↑ 13.11.15 Straftaten "im sehr niedrigen sechsstelligen Bereich", Die Welt, https://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article148812603/Straftaten-im-sehr-niedrigen-sechsstelligen-Bereich.html

- 1 2 (www.dw.com), Deutsche Welle. "Report: Refugee-related crimes in Germany increase less than influx of asylum seekers | NRS-Import | DW.COM | 17.02.2016". DW.COM. Retrieved 2016-04-28.

- ↑ "Identifying the Roots of Immigrant Crime". DW.COM.

- ↑ Dünkel, Frieder. "Migration and ethnic minorities in Germany: impacts on youth crime, juvenile justice and youth imprisonment" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 January 2016.

- 1 2 Piopiunik, Marc; Ruhose, Jens. "Immigration, regional conditions, and crime: evidence from an allocation policy in Germany". European Economic Review. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2016.12.004.

- ↑ https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/donald-trump-germany-crime-rate-immigrants-migrants-refugees-a8404786.html

- 1 2 "BKA - Bundeslagebilder Organisierte Kriminalität - Bundeslagebild Organisierte Kriminalität 2017". www.bka.de (in German). p. 13. Retrieved 2018-08-11.

- ↑ "BKA - Bundeslagebilder Organisierte Kriminalität - Bundeslagebild Organisierte Kriminalität 2017". www.bka.de (in German). p. 16. Retrieved 2018-08-11.

- ↑ Ghadban, Ralph (28 September 2018). "Die Macht der Clans". sueddeutsche.de (in German). ISSN 0174-4917. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ↑ Messerangriff mitten in Ravensburg, Frankfurter Allgemeine, 29 September 2018

- ↑ "Identifying the Roots of Immigrant Crime". DW.COM.

- 1 2 3 Schaaf, Julia. "Arabische Kriminelle in Deutschland: Das regeln wir unter uns". FAZ.NET (in German). ISSN 0174-4909. Retrieved 2018-08-31.

- ↑ Büscher, Wolfgang (2018-03-04). "Arabische Großfamilien: Null-Toleranz-Strategie soll kriminelle Clans zerschlagen". DIE WELT. Retrieved 2018-04-29.

- ↑ WELT (2017-12-25). "Berlin befreit Straßen von Schutzgeld-Erpressungen – „Ergeben uns nicht"". DIE WELT. Retrieved 2018-04-29.

- ↑ Behrendt, Michael (2016-04-10). "Organisiertes Verbrechen: In Berlin regieren arabische Clans". DIE WELT. Retrieved 2018-04-29.

- 1 2 Schmalz, Alexander. "20 Großfamilien in Berlin: Clans haben die Straßen aufgeteilt". Berliner Zeitung (in German). Retrieved 2018-07-21.

- ↑ "Sogar Kleingartenkolonie dabei: Polizei beschlagnahmt 77 Immobilien von arabischem Clan". Berliner Zeitung (in German). Retrieved 2018-08-22.

- ↑ Berlin, Berliner Morgenpost -. "Berliner Gefängnisse: Inhaftierte aus mehr als 90 Ländern" (in German). Retrieved 2018-10-02.

- ↑ "Zwei Sonder-Staatsanwälte kämpfen gegen Clankriminalität". Dülmener Zeitung (in German). 22 June 2018.

- 1 2 "Ausländer-Kriminalität in Hamburg: Die Zahlen der Polizei" [Foreign crime in Hamburg: The figures of the police]. Hamburger Abendblatt (in German). 21 September 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- 1 2 "169 Sexual-Straftaten durch Zuwanderer!" [169 Sexual offenses by immigrants!]. Bild.de (in German). 5 December 2016. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ↑ "Innenminister Ulbig stellt "Lagebericht Asyl und Kriminalitätsentwicklung Zuwanderer" vor" [Minister of the Interior Ulbig presents 'Situation Report on Asylum and the Development of Crime Migrants']. Sächsische Zeitung (in German). 5 December 2016. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ↑ "Germany: Migrants 'may have fuelled violent crime rise'". BBC. 3 January 2018. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ↑ "Youth knifing spate alarms German police unions". Deutshe Welle. 2 April 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ↑ WELT (2018-03-14). "Flensburg: 17-Jährige erstochen – Tatverdächtiger aus Afghanistan". DIE WELT. Retrieved 2018-04-29.

- ↑ String of knife attacks further fuels debate over refugees and violence, The Local, 27 March 2018

- ↑ S. SIEVERING (26 March 2018). "BLOODY WEEKEND: knife attacks throughout Germany". Bild (in German). Retrieved 15 April 2018.

More and more knife attacks in Germany. BILD documents what happened this weekend alone.

- ↑ "24-YEAR-OLD STABBED BY TEENAGERS: THE VICTIM". Tag 24 (in German). 29 March 2018. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

The deed has triggered a political debate on juvenile delinquency and the integration of refugees.

- ↑ Vergewaltigte Camperin bei Bonn: Angeklagter zu elfeinhalb Jahren Haft verurteilt, Spiegel online, 19. Oktober 2017.

- ↑ Esra TÜRKEL. "'Sözünüzü Tutun'". Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ↑ German Missions in the United States. "Immigration and Cultural Issues between Germany and its Turkish Population Remain Complex". Retrieved 29 October 2016.

With a population of roughly 4 million within Germany's borders, Turks make up Germany's largest minority demographic.

- ↑ David Reay (April 13, 2017). "Why German Turks are numerous, divided and bitter". Handelsblatt Global. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ↑ Berliner Zeitung. "Morgen beginnt Prozeß um den Tod des Türken Warum mußte Mete Eksi sterben?". Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ↑ Hurriyet. "Aslı'nın acı sırrı". Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- ↑ "25 years on, tense Germany and Turkey mark deadly neo-Nazi attack". The Local.de. 29 May 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ↑ Benček, David; Strasheim, Julia (2016). "Refugees welcome? A dataset on anti-refugee violence in Germany". Research & Politics. 3 (4): 205316801667959. doi:10.1177/2053168016679590. ISSN 2053-1680.

- ↑ BKA zählt fast 800 Angriffe auf Flüchtlingsunterkünfte, Die Zeit, 19 October 2016, in German

- ↑ "Germany hate crime: Nearly 10 attacks a day on migrants in 2016". BBC. 26 February 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ↑ Jäckle, Sebastian; König, Pascal D. (2016-08-16). "The dark side of the German 'welcome culture': investigating the causes behind attacks on refugees in 2015". West European Politics. 40 (2): 223–251. doi:10.1080/01402382.2016.1215614. ISSN 0140-2382.

- ↑ "The Impact of Xenophobic Violence on the Integration of Immigrants". Retrieved 2018-10-05.

- ↑ Amy Southall (4 May 2017). "Germany's 'refugee hunters': The violent vigilantes striking fear into asylum seekers". TalkRadio. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ↑ Jon Sharman (20 February 2018). "German man attacks three immigrants with knife 'because he was angry about Merkel's refugee policy'". The Independent. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ↑ Abby Young-Powell (28 August 2018). "Right-wing mobs creating 'civil war' in Germany after second night of violence in Chemnitz". The Telegraph. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- 1 2 3 Editorial, Reuters. "More girls at risk of genital mutilation in Germany - report". U.S. Retrieved 2018-09-02.

- ↑ Réthy, Laura (6 February 2014). "Wo beschnittene Frauen ihre Würde zurückerlangen". Die Welt. Axel Springer AG. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

- ↑ WELT (2018-07-24). "Frauen: In Deutschland 65.000 Frauen und Mädchen von Genitalverstümmelung betroffen". DIE WELT. Retrieved 2018-09-02.

- ↑ Cottee, Stanley (13 October 2015). "Europe's moral panic about the migrant Muslim 'other'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- ↑ "German Refugee Policy Under Fire After a Week of Bloodshed". The New York Times. Associated Press. 25 July 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- ↑ ANTON TROIANOVSKI. "New Berlin Crime Adds Fuel to German Debate Over Surveillance and Immigration". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

A week after a deadly terror attack at a Christmas market, another crime in the German capital is feeding a debate over how the country balances security and civil liberties. [...] By Tuesday, the suspects in the case had been detained. They were asylum seekers—six from Syria and one from Libya, according to police.

- ↑ Benhold, Katrin (17 January 2018). "A Girl's Killing Puts Germany's Migration Policy on Trial". New York Times. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- ↑ (www.dw.com), Deutsche Welle. "Suspect in murder of German teen caught in northern Iraq | DW | 08.06.2018". DW.COM. Retrieved 2018-06-09.

- ↑ (www.dw.com), Deutsche Welle. "Germany: Politicians seek answers after teenager's murder suspect's flight | DW | 08.06.2018". DW.COM. Retrieved 2018-06-09.