Hospital emergency codes

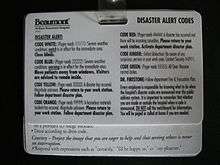

Hospital emergency codes are coded messages often announced over a public address system of a hospital to alert staff to various classes of on-site emergencies. The use of codes is intended to convey essential information quickly and with minimal misunderstanding to staff while preventing stress and panic among visitors to the hospital. Such codes are sometimes posted on placards throughout the hospital or are printed on employee identification badges for ready reference.

Hospital emergency codes have often varied widely by location, even between hospitals in the same community. Confusion over these codes has led to the proposal for and sometimes adoption of standardized codes. In many American, Canadian, New Zealand and Australian hospitals, for example "code blue" indicates a patient has entered cardiac arrest, while "code red" indicates that a fire has broken out somewhere in the hospital facility.

In order for a code call to be useful in activating the response of specific hospital personnel to a given situation, it is usually accompanied by a specific location description (e.g., "Code red, Second floor, corridor three, room two-twelve"). Other codes, however, only signal hospital staff generally to prepare for the fallout of some external event such as a natural disaster.

Color code standardization

- Australia:

- Australian hospitals and other buildings are covered by Australian Standard 4083 (1997) and many are in the process of changing to those standards.[1]

- Code Red: Fire

- Code Blue: Medical Emergency

- Code Yellow: Internal Emergency

- Code Brown: External Emergency (disaster, mass casualties etc.)

- Code Black: Personal Threat

- Code Black Alpha: Missing or Abducted Infant or Child

- Code Black Beta: Active Shooter

- Code Black J: Self-harm

- Code Purple: Bomb Threat

- Code Orange: Evacuation

- Code CBR: Chemical, Biological or Radiological Contamination

- Australian hospitals and other buildings are covered by Australian Standard 4083 (1997) and many are in the process of changing to those standards.[1]

- Canada:

- Codes used in British Columbia, prescribed by the British Columbia Ministry of Health.[2]

- Code Red: Fire

- Code Blue: Cardiac Arrest

- Code Orange: Disaster or Mass Casualties

- Code Green: Evacuation

- Code Yellow: Missing Patient

- Code Amber: Missing or Abducted Infant or Child

- Code Black: Bomb Threat

- Code White: Aggression

- Code Brown: Hazardous Spill

- Code Grey: System Failure

- Code Pink: Pediatric Emergency and/or Obstetrical Emergency

- Codes in Alberta are prescribed by Alberta Health Services.[3]

- Code Red: Fire

- Code Blue: Cardiac Arrest/Medical Emergency

- Code Orange: Mass Casualty Incident

- Code Green: Evacuation

- Code Yellow: Missing Patient

- Code Black: Bomb Threat/Suspicious Package

- Code White: Violence/Aggression

- Code Brown: Chemical Spill/Hazardous Material

- Code Grey: Shelter in Place/Air Exclusion

- Code Purple: Hostage Situation

- In Ontario, a standard emergency response code set by the Ontario Hospital Association is used, with minor variations for some hospitals.[4][5][6]

- Code Red: Fire

- Code Silver: Gun Threat/Shooter

- Code Blue: Cardiac Arrest/Medical Emergency – Adult

- Code Orange: Disaster

- Code Orange CBRN: CBRN (Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear) Disaster

- Code Green: Evacuation (Precautionary)

- Code Green STAT: Evacuation (Crisis)

- Code Yellow: Missing Person

- Code Amber (code purple): Missing Child/Child Abduction

- Code Black: Bomb Threat/Suspicious Object

- Code White: Violent/Behavioural Situation

- Code Brown: In-facility Hazardous Spill

- Code Grey: Infrastructure Loss or Failure

- Code Grey Button-down: External Air Exclusion

- Code Pink: Cardiac Arrest/Medical Emergency – Infant/Child

- Code Purple: Hostage Taking/Gang Activity

- Code Aqua: Flood

- Codes used in British Columbia, prescribed by the British Columbia Ministry of Health.[2]

- United States:

- In 2000, the Hospital Association of Southern California (HASC)[7][8][9] determined that a uniform code system is needed after "three persons were killed in a shooting incident at an area medical center after the wrong emergency code was called." While codes for fire (red) and medical emergency (blue) were similar in 90% of California hospitals queried, 47 different codes were used for infant abduction and 61 for combative person. In light of this, HASC published a handbook titled "Healthcare Facility Emergency Codes: A Guide for Code Standardization" listing various codes and has strongly urged hospitals to voluntarily implement the revised codes.

- In 2003, Maryland mandated that all acute hospitals in the state have uniform codes.[10]

- In 2008, the Oregon Association of Hospitals & Health Systems, Oregon Patient Safety Commission, and Washington State Hospital Association formed a taskforce to standardize emergency code calls under the leadership of the Dr. Lawrence Schecter, Chief Medical Officer, Providence Regional Medical Center Everett.[11] After both states had conducted a survey from all hospital members, the taskforce found many hospitals used the same code for fire (code Red); however, there were tremendous variations existed for codes representing respiratory and cardiac arrest, infant and child abduction, and combative person. After deliberations and decisions, the taskforce suggested the following as the Hospital Emergency Code:[12]

- Code Blue: Heart or Respiration Stops (An adult or child’s heart has stopped or they are not breathing.)

- Code Red: Fire (alternative: Massive Postpartum Hemorrhage)

- Code Pink: Infant abduction

- Code Orange: Hazardous Spills (A hazardous material spill or release; Unsafe exposure to spill.)

- Code Silver: Weapon or Hostage Situation

- Code Grey: Combative Person (Combative or abusive behavior by patients, families, visitors, staff or physicians) If a weapon is involved “CODE SILVER” should be called.

- Amber Alert: Infant/ Child Abduction

- Internal Triage: Internal Emergency (Internal emergency in multiple departments including: Bomb or bomb threat; Computer network down; Major plumbing problems; and Power or telephone outage.)

- External Triage: External Disaster (External emergencies impacting hospital including: Mass casualties; Severe weather; Massive power outages; and Nuclear, biological, and chemical accidents)

- Rapid Response Team: Medical Team Needed at Bedside (A patient’s medical condition is declining and needs an emergency medical team at the bedside) Prior to heart or respiration stopping

- Code Clear: Announced when emergency is over

- In 2015, the South Carolina Hospital Association formed a work group to develop plain language standardization code recommendations. Abolishing all color codes was suggested.[13]

Codes

Note: Different codes are used in different hospitals.

Code Blue

Medical lockdown

"Code Blue" is generally used to indicate a patient requiring resuscitation or in need of immediate medical attention, most often as the result of a respiratory arrest or cardiac arrest (by cardiac arrest is nowadays considered to not just mean asystole, the most severe example, but also pulseless electrical activity [PEA], coarse or fine ventricular fibrillation [VF or V-fib], or unstable irregular ventricular tachycardia [VT or V-tach]- some of these lethal, non-circulating arrhythmias are shockable by a defibrillator, some are not and are primarily treated by epinephrine and similar drugs). When called overhead, the page takes the form of "Code Blue, (floor), (room)" to alert the resuscitation team where to respond. Every hospital, as a part of its disaster plans, sets a policy to determine which units provide personnel for code coverage. In theory any medical professional may respond to a code, but in practice the team makeup is limited to those with advanced cardiac life support or other equivalent resuscitation training. Frequently these teams are staffed by physicians (from anesthesia and internal medicine in larger medical centers or the Emergency physician in smaller ones), respiratory therapists, pharmacists, and nurses. A code team leader will be a physician in attendance on any code team; this individual is responsible for directing the resuscitation effort and is said to "run the code". This phrase was coined at Bethany Medical Center in Kansas City, Kansas.[14] The term "code" by itself is commonly used by medical professionals as a slang term for this type of emergency, as in "calling a code" or describing a patient in arrest as "coding" or "coded".

In some hospitals or other medical facilities, the resuscitation team may purposely respond slowly to a patient in cardiac arrest, a practice known as "slow code", or may fake the response altogether for the sake of the patient's family, a practice known as "show code".[15] Such practices are ethically controversial,[16] and are banned in some jurisdictions.

Variations

"Plan Blue" was used at St. Vincent's Hospital in New York City to indicate arrival of a trauma patient so critically injured that even the short delay of a stop in the ER for evaluation could be fatal; the "Plan Blue" was called out to alert the surgeon on call to go immediately to the ER entrance and take the patient for immediate surgery. This was illustrated in an episode of Trauma: Life in the ER, entitled "West Side Stories".

"Doctor" Codes

"Doctor" codes are often used in hospital settings for announcements over a general loudspeaker or paging system that might cause panic or endanger a patient's privacy. Most often, "Doctor" codes take the form of "Paging Dr. Sinclair", where the doctor's "name" is a code word for a dangerous situation or a patient in crisis, e.g.: "Paging Doctor Firestone, third floor," to indicate a possible fire on the floor specified.

"Resus" Codes

Specific to emergency medicine, incoming patients in immediate danger of life or limb, whether presenting via ambulance or walk-in triage, are paged locally within the emergency department as "Resus" [ri:səs] codes. These codes indicate the type of emergency (general medical, trauma, cardiopulmonary or neurological) and type of patient (adult or pediatric). An estimated time of arrival may be included, or "now" if the patient is already in the department. The patient is transported to the nearest open trauma bay or evaluation room, and is immediately attended by a designated team of physicians and nurses for purposes of immediate stabilization and treatment.

See also

- Inspector Sands, code used over PA system in British public transport to indicate a serious situation

References

- 1 2 AS 4083-1997 Planning for emergencies-Health care facilities

- ↑ "BC Standardized Hospital Colour Codes" (PDF). Victoria, BC: British Columbia Ministry of Health. 21 January 2011. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ↑ "AHS Emergency / Disaster Management" (PDF). Edmonton, AB: Alberta Health Services. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- ↑ "OHA Emergency Management Toolkit" (PDF). Toronto, ON: Ontario Hospital Association. 31 March 2013. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ↑ "North York General Hospital – Emergency Preparedness". nygh.on.ca.

- ↑ "Emergency Codes". sunnybrook.ca.

- 1 2 "Hospital Emergency Codes".

- ↑ California Healthcare Association News Briefs July 12, 2002Vol. 35 No. 27 Archived December 2, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "2014 Emergency Codes".

- ↑ DSD.state.md.us

- ↑ "Standardization Emergency Codes Executive Summary" (PDF). Washington State Hospital Association. October 2008. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ↑ "Standardization Poster Emergency Code Call" (PDF). Washington State Hospital Association. January 2009. Retrieved http://www.wsha.org/wp-content/uploads/Standardization_PosterEmergencyCodeCallsAA.pdf. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Plain Language Emergency Codes Implementation Tool Kit" (PDF). South Carolina Hospital Association. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ↑ "Unplugged". google.com.

- ↑ "Slow Codes, Show Codes and Death". The New York Times. 22 August 1987. Retrieved 2013-04-06.

- ↑ DePalma, Judith A.; Miller, Scott; Ozanich, Evelyn; Yancich, Lynne M. (November 1999). "'Slow' Code: Perspectives of a Physician and Critical Care Nurse". Critical Care Nursing Quarterly. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. 22 (3): 89–99. doi:10.1097/00002727-199911000-00014. ISSN 1550-5111.