History of human migration

- See Human migration for a discussion of contemporary migration.

Human migration is the movement by people from one place to another with the intention of settling temporarily or permanently in the new location. It typically involves movements over long distances and from one country or region to another.

Historically, early human migration includes the peopling of the world, i.e. migration to world regions where there was previously no human habitation, during the Upper Paleolithic. Since the Neolithic, most migrations (except for the peopling of remote regions such as the Arctic or the Pacific), migration was predominantly warlike, consisting of conquest or Landnahme on the part of expanding populations. Colonialism involves expansion of sedentary populations into previously only sparsely settled territories or territories with no permanent settlements. In the modern period, human migration has primarily taken the form of migration within and between existing sovereign states, either controlled (legal immigration) or uncontrolled and in violation of immigration laws (illegal immigration).

Migration can be voluntary or involuntary. Involuntary migration includes forced displacement (in various forms such as deportation, slave trade, trafficking in human beings) and flight (war refugees, ethnic cleansing).

Pre-modern history

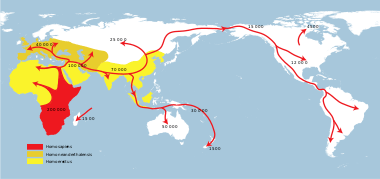

Historical migration of human populations begins with the movement of Homo erectus out of Africa across Eurasia about 1.75 million years ago. Homo sapiens appears to have occupied all of Africa about 150,000 years ago, moved out of Africa 70,000 years ago (or, according to more recent studies, as early as 125,000 years ago into Asia,[2][3] and even as early as 270,000 years ago),[4][5] and had spread across Australia, Asia and Europe by 40,000 BCE. Migration to the Americas took place 20,000 to 15,000 years ago. Nonetheless, by 2000 years ago, most of the Pacific Islands were colonized. Later population movements notably include the Neolithic Revolution, Indo-European expansion, and the Early Medieval Great Migrations including Turkic expansion. In some places, such as Turkey and Azerbaijan, there was a substantial cultural transformation after the migration of relatively small elite populations.[6] It is considered that the Roman and Norman conquests of Britain were similar examples, while "the most hotly debated of all the British cultural transitions is the role of migration in the relatively sudden and drastic change from Romano-Britain to Anglo-Saxon Britain", which may be explained by a possible "substantial migration of Anglo-Saxon Y chromosomes into Central England (contributing 50%–100% to the gene pool at that time)."[7]

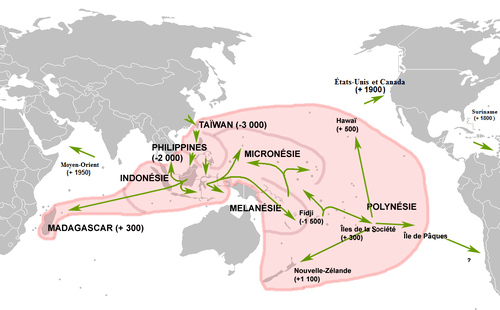

Early humans migrated due to many factors such as changing climate and landscape and inadequate food supply. The evidence indicates that the ancestors of the Austronesian peoples spread from the South Chinese mainland to Taiwan around 8,000 years ago. Evidence from historical linguistics suggests that it is from this island that seafaring peoples migrated, perhaps in distinct waves separated by millennia, to the entire region encompassed by the Austronesian languages. It is believed that this migration began around 6,000 years ago.[8] Indo-Aryan migration from the Indus Valley to the plain of the River Ganges in Northern India is presumed to have taken place in the Middle to Late Bronze Age, contemporary with the Late Harappan phase in India (around 1700 to 1300 BC). From 180 BC, a series of invasions from Central Asia followed, including those led by the Indo-Greeks, Indo-Scythians, Indo-Parthians and Kushans in the northwestern Indian subcontinent.[9][10][11]

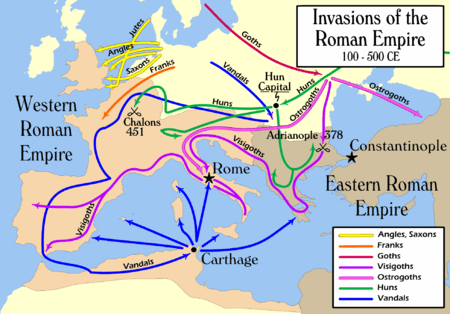

From 728 BC, the Greeks began 250 years of expansion, settling colonies in several places, including Sicily and Marseille. In Europe, there were two big migrations: the Celtic people and the later Migration Period from the North and East. Both may be examples of general cultural change sparked by primarily elite and warrior migration. A smaller migration was the Magyars moving into Pannonia (modern-day Hungary). Turkic peoples spread from their homeland in modern Turkestan across most of Central Asia into Europe and the Middle East between the 6th and 11th centuries AD. Recent research suggests that Madagascar was uninhabited until Austronesian seafarers from Indonesia arrived during the 5th and 6th centuries AD. Subsequent migrations from both the Pacific and Africa further consolidated this original mixture, and Malagasy people emerged.[12]

Before the expansion of the Bantu languages and their speakers, the southern half of Africa is believed to have been populated by Pygmies and Khoisan-speaking people, who today occupy the arid regions around the Kalahari Desert, and the forest of Central Africa. By about 1000 AD, Bantu migration had reached modern day Zimbabwe and South Africa. The Banu Hilal and Banu Ma'qil were a collection of Arab Bedouin tribes from the Arabian Peninsula who migrated westwards via Egypt between the 11th and 13th centuries. Their migration strongly contributed to the Arabisation and Islamisation of the western Maghreb, which was until then dominated by Berber tribes. Ostsiedlung was the medieval eastward migration and settlement of Germans. The 13th century was the time of the great Mongol and Turkic migrations across Eurasia.[13]

Between the 11th and 18th centuries, there were numerous migrations in Asia. The Vatsayan Priests migrated from the eastern Himalaya hills to Kashmir during the Shan invasion in the 13th century. They settled in the lower Shivalik Hills in the 13th century to sanctify the manifest goddess. In the Ming occupation, the Vietnamese expanded southward; this is known as nam tiến (southward expansion).[14] Manchuria was separated from China proper by the Inner Willow Palisade, which restricted the movement of the Han Chinese into Manchuria during the early Qing Dynasty, as the area was off-limits (British English: out of bounds) to the Han until the Qing started colonizing the area with them later on in the dynasty's rule.[15]

The Age of Exploration and European colonialism has led to an accelerated pace of migration since Early Modern times. In the 16th century, perhaps 240,000 Europeans entered American ports.[16] In the 19th century, over 50 million people left Europe for the Americas.[17] The local populations or tribes, such as the Aboriginal people in Canada, Brazil, Argentina, Australia, Japan[18] and the United States, were usually numerically overwhelmed by the settlers.

Modern history

Industrialization

When the pace of migration had accelerated since the 18th century already (including the involuntary slave trade), it would increase further in the 19th century. Manning distinguishes three major types of migration: labor migration, refugee migrations, and urbanization. Millions of agricultural workers left the countryside and moved to the cities causing unprecedented levels of urbanization. This phenomenon began in Britain in the late 18th century and spread around the world and continues to this day in many areas.

Industrialization encouraged migration wherever it appeared. The increasingly global economy globalized the labour market. The Atlantic slave trade diminished sharply after 1820, which gave rise to self-bound contract labour migration from Europe and Asia to plantations. Overpopulation, open agricultural frontiers, and rising industrial centres attracted voluntary migrants. Moreover, migration was significantly made easier by improved transportation techniques.

Romantic nationalism also rose in the 19th century, and, with it, ethnocentrism. The great European industrial empires also rose. Both factors contributed to migration, as some countries favored their own ethnicity over outsiders and other countries appeared to be considerably more welcoming. For example, the Russian Empire identified with Eastern Orthodoxy, and confined Jews, who were not Eastern Orthodox, to the Pale of Settlement and imposed restrictions. Violence was also a problem. The United States was promoted as a better location, a "golden land" where Jews could live more openly.[19] Another effect of imperialism, colonialism, led to the migration of some colonizing parties from "home countries" to "the colonies", and eventually the migration of people from "colonies" to "home countries".[20]

Transnational labor migration reached a peak of three million migrants per year in the early twentieth century. Italy, Norway, Ireland and the Guangdong region of China were regions with especially high emigration rates during these years. These large migration flows influenced the process of nation state formation in many ways. Immigration restrictions have been developed, as well as diaspora cultures and myths that reflect the importance of migration to the foundation of certain nations, like the American melting pot. The transnational labor migration fell to a lower level from the 1930s to the 1960s and then rebounded.

The United States experienced considerable internal migration related to industrialization, including its African American population. From 1910 to 1970, approximately 7 million African Americans migrated from the rural Southern United States, where blacks faced both poor economic opportunities and considerable political and social prejudice, to the industrial cities of the Northeast, Midwest and West, where relatively well-paid jobs were available.[21] This phenomenon came to be known in the United States as its own Great Migration, although historians today consider the migration to have two distinct phases. The term "Great Migration", without a qualifier, is now most often used to refer the first phase, which ended roughly at the time of the Great Depression. The second phase, lasting roughly from the start of U.S. involvement in World War II to 1970, is now called the Second Great Migration. With the demise of legalised segregation in the 1960s and greatly improved economic opportunities in the South in the subsequent decades, millions of blacks have returned to the South from other parts of the country since 1980 in what has been called the New Great Migration.

World wars and aftermath

The First and Second World Wars, and wars, genocides, and crises sparked by them, had an enormous impact on migration. Muslims moved from the Balkan to Turkey, while Christians moved the other way, during the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. In April 1915 the Ottoman government embarked upon the systematic decimation of its civilian Armenian population. The persecutions continued with varying intensity until 1923 when the Ottoman Empire ceased to exist and was replaced by the Republic of Turkey. The Armenian population of the Ottoman state was reported at about two million in 1915. An estimated one million had perished by 1918, while hundreds of thousands had become homeless and stateless refugees. By 1923 virtually the entire Armenian population of Anatolian Turkey had disappeared. Four hundred thousand Jews had already moved to Palestine in the early twentieth century, and numerous Jews to America, as already mentioned. The Russian Civil War caused some three million Russians, Poles, and Germans to migrate out of the new Soviet Union. Decolonization following the Second World War also caused migrations.[22][23]

The Jewish communities across Europe, the Mediterranean and the Middle East were formed from voluntary and involuntary migrants. After the Holocaust (1938 to 1945), there was increased migration to the British Mandate of Palestine, which became the modern state of Israel as a result of the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine.

Provisions of the Potsdam Agreement from 1945 signed by victorious Western Allies and the Soviet Union led to one of the largest European migrations, and the largest in the 20th century. It involved the migration and resettlement of close to or over 20 million people. The largest affected group were 16.5 million Germans expelled from Eastern Europe westwards. The second largest group were Poles, millions of whom were expelled westwards from eastern Kresy region and resettled in the so-called Recovered Territories (see Allies decide Polish border in the article on the Oder-Neisse line). Hundreds of thousands of Poles, Ukrainians (Operation Vistula), Lithuanians, Latvians, Estonians and some Belarusians were expelled eastwards from Europe to the Soviet Union. Finally, many of the several hundred thousand Jews remaining in Eastern Europe after the Holocaust migrated outside Europe to Israel and the United States.

Partition of India

In 1947, upon the Partition of India, large populations moved from India to Pakistan and vice versa, depending on their religious beliefs. The partition was created by the Indian Independence Act 1947 as a result of the dissolution of the British Indian Empire. The partition displaced up to 17 million people in the former British Indian Empire,[24] with estimates of loss of life varying from several hundred thousand to a million.[25] Muslim residents of the former British India migrated to Pakistan (including East Pakistan, now Bangladesh), whilst Hindu and Sikh residents of Pakistan and Hindu residents of East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) moved in the opposite direction.

In modern India, estimates based on industry sectors mainly employing migrants suggest that there are around 100 million circular migrants in India. Caste, social networks and historical precedents play a powerful role in shaping patterns of migration.

Research by the Overseas Development Institute identifies a rapid movement of labor from slower- to faster-growing parts of the economy. Migrants can often find themselves excluded by urban housing policies, and migrant support initiatives are needed to give workers improved access to market information, certification of identity, housing and education.[26]

In the riots which preceded the partition in the Punjab region, between 200,000 and 500,000 people were killed in the retributive genocide.[27][28] U.N.H.C.R. estimates 14 million Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims were displaced during the partition.[29] Scholars call it the largest mass migration in human history:[30] Nigel Smith, in his book Pakistan: History, Culture, and Government, calls it "history's greatest migration."[24]

Contemporary history (1960s to present)

See also

- Early human migrations

- Human migration

- Human timeline

- Refugee crisis

- Immigration § History

Further reading

- Reich, David (2018). Who We Are And How We Got Here - Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past. Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-1101870327. [31]

- Barbara Luethi: Migration and Migration History, version 2, in: Docupedia Zeitgeschichte, 06. July 2018

Notes and references

- ↑ Literature: Göran Burenhult: Die ersten Menschen, Weltbild Verlag, 2000. ISBN 3-8289-0741-5

- ↑ Bae, Christopher J.; Douka, Katerina; Petraglia, Michael D. (8 December 2017). "On the origin of modern humans: Asian perspectives". Science. 358 (6368): eaai9067. doi:10.1126/science.aai9067. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ↑ Kuo, Lily (10 December 2017). "Early humans migrated out of Africa much earlier than we thought". Quartz. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ↑ Zimmer, Carl (4 July 2017). "In Neanderthal DNA, Signs of a Mysterious Human Migration". New York Times. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ↑ Posth, Cosimo; et al. (4 July 2017). "Deeply divergent archaic mitochondrial genome provides lower time boundary for African gene flow into Neanderthals". Nature Communications. doi:10.1038/ncomms16046. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ↑ Tatjana Zerjal; Wells, R. Spencer; Yuldasheva, Nadira; Ruzibakiev, Ruslan; Tyler-Smith, Chris; et al. (2002). "A Genetic Landscape Reshaped by Recent Events: Y-Chromosomal Insights into Central Asia". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 71 (3): 466–482. doi:10.1086/342096. PMC 419996. PMID 12145751.

- ↑ Weale, Michael E.; Deborah A. Weiss; Rolf F. Jager; Neil Bradman; Mark G. Thomas (2002). "Y Chromosome Evidence for Anglo-Saxon Mass Migration". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 19 (7): 1008–1021. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004160. PMID 12082121. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- ↑ Language trees support the express-train sequence of Austronesian expansion, Nature

- ↑ The appearance of Indo-Aryan speakers, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Trivedi, Bijal P (2001-05-14). "Genetic evidence suggests European migrants may have influenced the origins of India's caste system". Genome News Network. J. Craig Venter Institute. Retrieved 2005-01-27.

- ↑ Genetic Evidence on the Origins of Indian Caste Populations -- Bamshad et al. 11 (6): 994, Genome Research

- ↑ Malagasy languages, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Migrations-&-World History

- ↑ The Le Dynasty and Southward Expansion

- ↑ From Ming to Qing

- ↑ "The Colombian Mosaic in Colonial America" by James Axtell Archived 2009-11-19 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ David Eltis Economic Growth and the Ending of the Transatlantic slave trade

- ↑ Report on a New Policy for the Ainu: A Critique

- ↑ See World of our Fathers, by Irving Howe, and particularly the first sixty or so pages of that book

- ↑ For example, people migrated from the Indian subcontinent to the UK during the Imperial era and afterwards.

- ↑ Great Migration, accessed 12/7/2007

- ↑ Patrick Manning, Migration in World History (2005) p 132-162.

- ↑ McKeown, Adam. "Global migrations 1846-1940". Journal of Global History. 15 (2): 155–189.

- 1 2 Pakistan:History, Culture, and Government by Nigel Smith, Page 112

- ↑ Metcalf, Barbara; Metcalf, Thomas R. (2006), A Concise History of Modern India (Cambridge Concise Histories), Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. Pp. xxxiii, 372, ISBN 0-521-68225-8.

- ↑ "Support for migrant workers: the missing link in India's development?". Overseas Development Institute. September 2008.

- ↑ Paul R. Brass (2003). "The partition of India and retributive genocide in the Punjab, 1946–47: means, methods, and purposes" (PDF). Journal of Genocide Research. p. 75 (5(1), 71–101). Retrieved 2014-08-16.

- ↑ "20th-century international relations (politics) : South Asia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2014-08-16.

- ↑ "Rupture in South Asia" (PDF). UNHCR. Retrieved 2014-08-16.

- ↑ Dr Crispin Bates (2011-03-03). "The Hidden Story of Partition and its Legacies". BBC. Retrieved 2014-08-16.

- ↑ Diamond, Jared (April 20, 2018). A Brand-New Version of Our Origin Story. The New York Times. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

Bibliography

Literature

Books

- Bauder, Harald. Labor Movement: How Migration Regulates Labor Markets, New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Behdad, Ali. A Forgetful Nation: On Immigration and Cultural Identity in the United States, Duke UP, 2005.

- Chaichian, Mohammad. Empires and Walls: Globalization, Migration, and Colonial Control, Leiden: Brill, 2014.

- Jared Diamond, Guns, germs and steel. A short history of everybody for the last 13'000 years, 1997.

- De La Torre, Miguel A., Trails of Terror: Testimonies on the Current Immigration Debate, Orbis Books, 2009.

- Fell, Peter and Hayes, Debra. What are they doing here? A critical guide to asylum and immigration, Birmingham (UK): Venture Press, 2007.

- Hoerder, Dirk. Cultures in Contact. World Migrations in the Second Millennium, Duke University Press, 2002

- Kleiner-Liebau, Désirée. Migration and the Construction of National Identity in Spain, Madrid / Frankfurt, Iberoamericana / Vervuert, Ediciones de Iberoamericana, 2009. ISBN 978-84-8489-476-6.

- Knörr, Jacqueline. Women and Migration. Anthropological Perspectives, Frankfurt & New York: Campus Verlag & St. Martin's Press, 2000.

- Knörr, Jacqueline. Childhood and Migration. From Experience to Agency, Bielefeld: Transcript, 2005.

- Manning, Patrick. Migration in World History, New York and London: Routledge, 2005.

- Migration for Employment, Paris: OECD Publications, 2004.

- OECD International Migration Outlook 2007, Paris: OECD Publications, 2007.

- Pécoud, Antoine and Paul de Guchteneire (Eds): Migration without Borders, Essays on the Free Movement of People (Berghahn Books, 2007)

- Abdelmalek Sayad. The Suffering of the Immigrant, Preface by Pierre Bourdieu, Polity Press, 2004.

- Stalker, Peter. No-Nonsense Guide to International Migration, New Internationalist, second edition, 2008.

- The Philosophy of Evolution (A.K. Purohit, ed.), Yash Publishing House, Bikaner, 2010. ISBN 81-86882-35-9.

Journals

- International Migration Review

- Migration Letters

- International Migration

- Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies

- Review of Economics of the Household

Online Books

- OECD International Migration Outlook 2007 (subscription service)

Documentary films

- The Short Life of José Antonio Gutierrez

- El Inmigrante, Directors: David Eckenrode, John Sheedy, John Eckenrode. 2005. 90 min. (U.S./Mexico)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Human migration. |

- iom.int, The International Organisation for Migration

- CIA World Factbook gives up-to-date statistics on net immigration by country.

- Western Sahara and Migration

- Stalker's Guide to International Migration Comprehensive interactive guide to modern migration issues, with maps and statistics

- Integration : Building Inclusive Societies (IBIS) UN Alliance of Civilisations online community on good practices of integration of migrants across the world

- migrations in history

- The importance of migrants in the modern world

- Mass migration as a travel business