History of cheese

The production of cheese predates recorded history. It originated through the transportation of milk in bladders made of ruminants' stomachs due to their inherent supply of rennet. There is no conclusive evidence indicating where cheese-making originated. However, it may have originated either in Europe, Central Asia, the Middle East, or the Sahara. Cheese-making was known in Europe at the earliest level of Hellenic myth.[1] According to Pliny the Elder, cheese became a sophisticated enterprise at the start of the ancient Rome era.[2] During the ancient Rome era, valued foreign cheeses were transported to Rome to satisfy the tastes of the social elite.

Earliest origins

Shards of pottery pierced with holes found in pile-dwellings are hypothesized to be cheese-strainers.[3] They are of the Urnfield culture on Lake Neuchatel and date back to 6,000 BCE. The earliest direct evidence of cheese-making dates back to 5,500 BCE in Kujawy, Poland.[4][5] For preservation purposes, cheese-making may have begun by the pressing and salting of curdled milk. Curdling milk in an animal's stomach made solid and better-textured curds, leading to the addition of rennet. Dairying existed around 4,000 BC in the grasslands of the Sahara.[6] Hard salted cheese is likely to have accompanied dairying from the outset. It is the only form in which milk can be kept in a hot climate. Animal skins and inflated internal organs provided storage vessels for a range of foodstuffs. Cheese produced in Europe, where climates are cooler than in the Middle East, required less salt for preservation. With less salt and acidity, the cheese became a suitable environment for useful microbes and molds, giving aged cheeses their pronounced and interesting flavors.

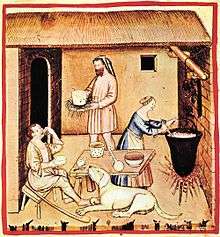

The earliest evidence of cheese (GA.UAR) is the Sumerian cuneiform texts of Third Dynasty of Ur, dated at the early second millennium BC.[7] Remains identified as cheese were found in the funeral meal in an Egyptian tomb dating around 2900 BC.[8]Visual evidence of Egyptian cheesemaking was found in Egyptian tomb murals in approximately 2000 BC.[9] The earliest cheeses were sour and salty and similar in texture to rustic cottage cheese or present-day feta. In Late Bronze Age Minoan-Mycenaean Crete, Linear B tablets recorded the inventorying of cheese, (Mycenaean Greek in Linear B: 𐀶𐀫, tu-ro; later Greek: τυρός)[10][11] flocks and shepherds.[12] An Arab legend attributes the discovery of cheese to an Arab trader who used this method of storing milk.[13][14] However, cheese was already well-known among the Sumerians.[15] Preserved cheese dating from 1615 BC was found in the Taklamakan Desert in Xinjiang, China.[16] In 2018, archeologists from Cairo University and the University of Catania reported the discovery of the oldest known cheese from Egypt. Discovered in the Saqqara necropolis, it is around 3200 years old. [17]

Ancient Greece and Rome

Ancient Greek mythology credited Aristaeus with the discovery of cheese. Homer's Odyssey (late 8th century BC) describes the Cyclops producing and storing sheep's and goat's milk and cheese:

| “ | We soon reached his cave, but he was out shepherding, so we went inside and took stock of all that we could see. His cheese-racks were loaded with cheeses, and he had more lambs and kids than his pens could hold... When he had so done he sat down and milked his ewes and goats, all in due course, and then let each of them have her own young. He curdled half the milk and set it aside in wicker strainers.[18] |

” |

A letter of Epicurus to his patron requests a wheel of hard cheese so that he may make a feast whenever he wishes. Pliny recorded the Roman tradition that Zoroaster had lived on cheese.[19]

By Roman times, cheese-making was a mature art and common food group. Columella's De Re Rustica (circa 65 CE) details a cheese-making process involving rennet coagulation, pressing of the curd, salting, and aging. Pliny's Natural History (77 CE) devotes two chapters (XI, 96-97) to the diversity of cheeses enjoyed by Romans of the early Empire. He stated that the best cheeses came from pagi near Nîmes, and were identifiable as Lozère and Gévaudan and had to be eaten fresh.

Post-Roman Europe

Most cheeses were initially recorded in the late Middle Ages. Cheddar was recorded around 1500 CE, Parmesan was founded in 1597, Gouda in 1697, and Camembert in 1791.[20] Cheeses diversified in Europe with locales developing their own traditions and products when Romanized populations encountered unfamiliar neighbors with their own cheese-making traditions. As long-distance trade collapsed, only travelers encountered unfamiliar cheeses. Charlemagne's first encounter with an edible rind white cheese forms one of the constructed anecdotes of Notker's Life of the Emperor.[21] Cheese-making in manor and monastery intensified local characteristics imparted by local bacterial flora while the identification of monks with cheese is sustained through modern marketing labels.[22] This also led to a diversity of cheese types. Today, Britain has 15 protected cheeses from approximately 40 types listed by the British Cheese Board. The British Cheese Board claims a total number of about 700 different products (including similar cheeses produced by different companies).[23] France has 50 protected cheeses, Italy 46, and Spain 26. France also has at least 1,800 raw milk cheese products[24] and probably more than 2,000 when including pasteurized cheese.[25] Furthermore, French proverb states that there is a different French cheese for every day of the year. Late French general and statesman, Charles de Gaulle, once asked "how can you govern a country in which there are 246 kinds of cheese?"[26] Meanwhile, the advancement of cheese art in Europe was slow during the centuries after Rome's fall. It became a staple of long-distance commerce,[27] was disregarded as peasant fare,[28] inappropriate on a noble table, and even harmful to one's health through the Middle Ages.[29]

In 1546, The Proverbs of John Heywood claimed "the moon is made of a greene cheese" (Greene is referred to being new or unaged).[30] Variations on this sentiment were long repeated and NASA exploited this myth for an April Fools' Day spoof announcement in 2006.[31]

Modern

Until its modern spread, along with European culture, cheese was nearly unheard of in Asian cultures and in the pre-Columbian Americas. It had limited use in sub-Mediterranean Africa. Although it is rarely considered a part of local ethnic cuisines outside Europe, the Middle East, and the Americas, cheese has become popular worldwide through the spread of European Imperialism and Euro-American culture.

The first factory for the industrial production of cheese opened in Switzerland in 1815. However, the large-scale production found real success in the United States. Credit goes to Jesse Williams, a dairy farmer from Rome, New York. Williams began making cheese in an assembly-line fashion using the milk from neighboring farms in 1851. Within decades, hundreds of dairy associations existed.

Mass-produced rennet began in the 1860s. By the turn of the century, scientists were producing pure microbial cultures. Previously, bacteria in cheese was derived from the environment or from recycling an earlier batch's whey. Pure cultures meant a standardized cheese could be produced. The mass production of cheese made it readily available to the poorer classes. Therefore, simple cost-effective storage solutions for cheese gained popularity. Ceramic cheese dishes, or cheese bells, became one of the most common ways to prolong the life of cheese in the home. It remained popular in most households until the introduction of the home refrigerator in 1913.[32]

Factory-made cheese overtook traditional cheese-making during the World War II era. Since then, factories have been the source of most cheese in America and Europe. Today, Americans buy more processed cheese than "real", factory-made cheese.[33]

See also

References

- ↑ The archaic myth of the culture-hero Aristaeus, who introduced bee-keeping and cheese-making before wine was known in Greece.

- ↑ "The History Of Cheese: From An Ancient Nomad's Horseback To Today's Luxury Cheese Cart". The Nibble. Lifestyle Direct, Inc. Retrieved 2009-10-15.

- ↑ Toussaint-Samat 2009:103.

- ↑ Salque M, Bogucki PI, Pyzel J, Sobkowiak-Tabaka I, Grygiel R, et al. (2012). "Earliest evidence for cheese making in the sixth millennium bc in northern Europe". Nature. Nature Publishing Group. 493: 522–525. doi:10.1038/nature11698. PMID 23235824. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ↑ Subbaraman, Nidhi (12 December 2012). "Art of cheese-making is 7,500 years old". Nature. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ↑ Simoons, Frederick J. (July 1971). "The antiquity of dairying in Asia and Africa". Geographical Review. American Geographical Society. 61 (3). JSTOR 213437.

- ↑ In NBC 11196 (5 NT 24, dated Shu-Sin 6), the 'abra's of Dumuzi, Ninkasi, and I'kur receive butter and cheese from the 'abra of Inanna, according to W.W. Hallo, "The House of Ur-Meme", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 1972; a Sumerian/Akkadian bilingual lexicon of ca 1900 BC lists twenty kinds of cheese.

- ↑ Walter Bryan Emery: A Funerary Repast in an Egyptian Tomb of the Archaic Period. Nederlands instituut voor het Nabije Oosten, Leiden 1962

- ↑ History of Cheese. accessed 2007/06/10

- ↑ "The Linear B word tu-ro". Palaeolexicon. Word study tool for ancient languages.

- ↑ τυρός. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ↑ Michael Ventris and John Chadwick, Documents in Mycenaean Greek, 2nd ed. (Cambridge University Press) 1973:572, 588; implications of modern pre-industrial Cretan pastoralists and cheese production for interpreting the archaeological record, are discussed by H. Blitzer, "Pastoral Life in the Mountains of Crete", 1990.

- ↑ Ridgwell, Jenny; Ridgway, Judy (1968). Food Around the World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-832728-5.

- ↑ Reich, Vicky (January 2002). "Cheese". Moscow Food Co-op. Archived from the original on May 30, 2012. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ↑ Carmona, Salvador; Ezzamel, Mahmoud (2007). "Accounting and accountability in ancient civilizations: Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt". Accounting and Accountability. Emeral Group Publishing. 20 (2). doi:10.2139/ssrn.1016353. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

In the Old Sumerian period, cheese delivery quotas of herdsmen in charge were recorded, using jars with standardized liquid capacity as measures (the traditional grain measures), in contrast to archaic times when cheese was counted in discrete units

- ↑ "Oldest Cheese Found". Retrieved February 25, 2015.

- ↑ "Ancient Egypt: Cheese discovered in 3,200-year-old tomb". Retrieved August 20, 2018.

- ↑ Samuel Butler's translation.

- ↑ Pliny's Natural History, iii .85.

- ↑ Smith, John H. (1995). Cheesemaking in Scotland - A History. The Scottish Dairy Association. ISBN 0-9525323-0-1.

- ↑ Notker, §15.

- ↑ Noted in passing by Maguelonne Toussaint-Samat A History of Food, 2nd ed. 2009:106.

- ↑ "British Cheese homepage". British Cheese Board. 2007. Retrieved 2009-10-15.

- ↑ "Profession formager magazine". Retrieved 2015-05-05.

- ↑ "How many cheeses are there in France ?". Retrieved 2015-05-05.

- ↑ Quoted in Newsweek, 1 October 1962, according to The Columbia Dictionary of Quotations (Columbia University Press, 1993 ISBN 0-231-07194-9 p 345). Numbers besides 246 are often cited in very similar quotes; whether these are misquotes or whether de Gaulle repeated the same quote with different numbers is unclear.

- ↑ Details of the local costs and export duties in importing cheese from Apulia to Florence, ca 1310-40, are included in Francesco di Balduccio Pergolotti's Practice of Commerce, translated in Robert Sabatino Lopez, Irving Woodworth Raymond, Medieval trade in the Mediterranean world: illustrative documents, 2001:117, no. 46.

- ↑ The stratification of medieval food is discussed in Stephen Mennell, All Manners of Food: Eating and Taste in England and France from the Middle Ages to the Present, 1996: "Eating in the Middle Ages: the social distribution of food", pp 41ff; Mennell observes, "Dairy produce very much remained identified with the lower orders and disdained by the grand", adding "one of the few ways in which peasants in the mountains of Provence had a dietary advantage over the archbishop [of Arles] was in their high consumption of cheese."

- ↑ William Edward Mead, The English Medieval Feast, 1931 notes "the advice to avoid peaches, apples, pears and cheese, etc., as injurious to health" as unintelligible to moderns.

- ↑ Cecil Adams (1999). "Straight Dope: How did the moon=green cheese myth start?". Retrieved October 15, 2005.

- ↑ Nemiroff, R.; Bonnell, J., eds. (1 April 2006). "Hubble Resolves Expiration Date For Green Cheese Moon". Astronomy Picture of the Day. NASA. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

- ↑ "Barfly Retro Fridge History". Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ↑ McGee, Harold (2004). On Food and Cooking (Revised Edition). Scribner. p. 54. ISBN 0-684-80001-2.

In the United States, the market for process cheese [...] is now larger than the market for 'natural' cheese, which itself is almost exclusively factory-made.