Food history

"Food history" is an interdisciplinary field that examines the history of food and nutrition, and the cultural, economic, environmental, and sociological impacts of food. Food history is considered distinct from the more traditional field of culinary history, which focuses on the origin and recreation of specific recipes.

The first journal in the field, Petits Propos Culinaires was launched in 1979 and the first conference on the subject was the 1981 Oxford Food Symposium.[1]

Middle Ages (500–1500)

English cooking has been influenced by foreign ingredients and cooking styles since the Middle Ages. Traditional meals have ancient origins, such as bread and cheese, roasted and stewed meats, meat and game pies, boiled vegetables and broths, and freshwater and saltwater fish. The 14th-century English cookbook, The Forme of Cury contains recipes for these, and dates from the royal court of Richard II.[2]

In the European Middle Ages, breakfast was not usually considered a necessary and important meal, and was practically nonexistent during the earlier medieval period. Monarchs and their entourages would spend lots of time around a table for meals. Only two formal meals were eaten per day—one at mid-day and one in the evening. The exact times varied by period and region, but this two-meal system remained consistent throughout the Middle Ages. Breakfast in some places was solely granted to children, the elderly, the sick, and to working men. Anyone else did not speak of or partake in eating in the morning. Eating breakfast meant that one was poor, was a low-status farmer or laborer who truly needed the energy to sustain his morning’s labor, or was too weak to make it to the large, midday dinner.[3] Because medieval people saw gluttony as a sin and a sign of weakness, men were often ashamed of eating breakfast.[4]

Noble travelers were an exception, as they were also permitted to eat breakfast while they were away from home. For instance, in March 1255 about 1512 gallons of wine were delivered to the English King Henry III at the abbey church at St. Albans for his breakfast throughout his trip. If a king were on religious pilgrimage, the ban on breakfast was completely lifted and enough supplies were compensated for the erratic quality of meals at the local cook shops during the trip.[5]

In the 13th century, breakfast when eaten sometimes consisted of a piece of rye bread and a bit of cheese. Morning meals would not include any meat, and would likely include ¼ gallon (1.1 L; 0.30 US gal) of low alcohol-content beers. Uncertain quantities of bread and ale could have been consumed in between meals.[6]

By the 15th century breakfast often included meat. By this time, noble men were seen to indulge in breakfast, making it more of a common practice, and by the early 16th century, recorded expenses for breakfast became customary. The 16th-century introduction of caffeinated beverages into the European diet was part of the consideration to allow breakfast. It was believed that coffee and tea aid the body in “evacuation of superfluities,” and was consumed in the morning.[7]

Potato

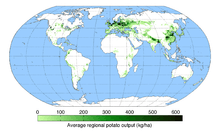

The potato was first domesticated in the region of modern-day southern Peru and extreme northwestern Bolivia It has since spread around the world and become a staple crop in many countries.[8]

According to conservative estimates, the introduction of the potato was responsible for a quarter of the growth in Old World population and urbanization between 1700 and 1900.[9] Following the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire, the Spanish introduced the potato to Europe in the second half of the 16th century, part of the Columbian exchange. The staple was subsequently conveyed by European mariners to territories and ports throughout the world. The potato was slow to be adopted by distrustful European farmers, but soon enough it became an important food staple and field crop that played a major role in the European 19th century population boom.[10] However, lack of genetic diversity, due to the very limited number of varieties initially introduced, left the crop vulnerable to disease. In 1845, a plant disease known as late blight, caused by the fungus-like oomycete Phytophthora infestans, spread rapidly through the poorer communities of western Ireland as well as parts of the Scottish Highlands, resulting in the crop failures that led to the Great Irish Famine.[11]

Rice

Rice probably originated in Korea or Australia and was widely grown in Asia 3000 years ago.[12] Muslims brought rice to Sicily with cultivation starting in the 9th century. After the 15th century, rice spread throughout Italy and then France, later propagating to all the continents during the age of European exploration. As a cereal grain, today it is the most widely consumed staple food for Asia and elsewhere. It is the #3 agricultural commodity (rice, 741.5 million tonnes in 2014), after sugarcane (1.9 billion tonnes) and maize ("corn" in the United States, 1.0 billion tonnes).[13]

Today, the majority of all rice produced comes from China, India, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Vietnam, Thailand, Myanmar, Pakistan, Philippines, Korea and Japan. Asia accounts for 87% of the world's total rice production.[14]

Early Modern Europe

Grain and livestock have long been the center of agriculture in France and England. After 1700, innovative farmers experimented with new techniques to increase yield, and looked into entirely new products such as hops, oilseed rape, artificial grasses, vegetables, fruit, dairy foods, commercial poultry, rabbits, and freshwater fish.[15]

Sugar began as an upper-class luxury product, but by 1700 Caribbean sugar plantations work by African slaves expanded production and lowered the price. By 1800 sugar was a staple of working-class diets. For them it symbolized increasing economic freedom and status.[16]

19th century

Laborers in Western Europe in the 18th century ate bread and gruel, often in a soup with greens and lentils, a little bacon, and occasionally potato or a bit of cheese. They washed it down with beer (Water was too contaminated), and a sip of milk. Three fourths of the food was derived from plants; fats came from plant oils. Meat was much more attractive, but very expensive. By 1870 the West European diet at about 16 kilos per person per year of meat, rising to 50 kilos by 1914, and 77 kilos in 2010. [17] Milk, and cheese, was seldom in the diet-- even in the early 20th century, it was still uncommon in Mediterranean diets.[18]

In the immigrant neighborhoods of fast-growing American industrial cities, housewives purchased ready-made food through street peddlers, hucksters, push carts, and small shops operated from private homes. This opened the way for the rapid entry of entirely new items such as pizza, spaghetti with meatballs, bagels, hoagies, pretzels, and pierogies into American eating habits, and firmly established fast food in the American culinary experience.[19]

20th century

The first half of the 20th century was characterized by two world wars with very high degrees of hunger and strict rationing, with the starvation of the civilian populations used as a powerful new weapon. In Germany during World War I the rationing system in urban areas virtually collapsed, with people eating animal fodder to survive the "Turnip winter."[20] In Allied countries, meat was diverted first to the soldiers, then to urgent civilian needs in Italy, Britain, France and Greece. Meat production was stretched to the limit in the United States, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and Argentina, with Oceanic shipping closely controlled by the British.[21]

In the first years of peace after the war ended in 1918, most of eastern and central Europe suffered severe food shortages. Outside help was on the way. The American Relief Administration (ARA) was set up under the American wartime food czar Herbert Hoover, and was charged with providing emergency food rations across Central and Eastern Europe. The ARA fed millions, including the inhabitants of Germany and the Soviet Union. After U.S. government funding for the ARA expired in the summer of 1919, the ARA became a private organization, raising millions of dollars from private donors. Under the auspices of the ARA, the European Children's Fund fed millions of starving children.[22]

The 1920s saw the introduction of new foodstuffs, especially fruit, transported from around the globe. After the World War many new food products became available to the typical household, with branded foods advertised for their convenience. Now instead of an experienced cook spending hours on difficult custards and puddings the housewife could purchase instant foods in jars, or powders that could be quickly mixed. Upscale households now had ice boxes or electric refrigerators, which made for better storage and the convenience of buying in larger quantities.[23]

In World War II, Nazi Germany made sure that its population was very well fed by seizing food supplies from occupied countries, and deliberately cutting off food to Jews, Poles, Russians and the Dutch.[24]

As part of the Marshall Plan 1948-1950, the United States provided taking logical expertise and financing for high productivity large-scale agribusiness operations in postwar Europe. Poultry was a favorite choice, with the rapid expansion in production, a sharp fall in prices, and widespread acceptance of the many ways to serve chicken.[25]

The Green Revolution was a technological breakthrough in plant productivity that increased agricultural production worldwide, particularly in the developing world. Research began in the 1930s and dramatic improvements in output became important in the late 1960s, and continue into the 21st century.[26] The initiatives resulted in the adoption of new technologies, including:

new, high-yielding varieties (HYVs) of cereals, especially dwarf wheats and rices, in association with chemical fertilizers and agro-chemicals, and with controlled water-supply (usually involving irrigation) and new methods of cultivation, including mechanization. All of these together were seen as a 'package of practices' to supersede 'traditional' technology and to be adopted as a whole.[27]

See also

References

- ↑ Raymond Sokolov. "http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1134/is_9_109/ai_67410994 Review: The Cambridge World History of Food]", Natural History

- ↑ Clarissa Dickson Wright, A History of English Food (2011) pp. 46-52.

- ↑ Heather Arndt Anderson (2013). Breakfast: A History. pp. 10–11.

- ↑ C.W. Bynum (1987). Holy feast and holy fast: The religious significance of food to medieval women. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ↑ Collin Spencer (2002). British Food: an Extraordinary Thousand Years of History. New York: Columbia University Press.

- ↑ M.A. Hicks (2001). Revolution and consumption in late medieval England. Woodbridge: Boydell Press.

- ↑ Heather Arndt Anderson, Breakfast: A History(2013).

- ↑ Redcliffe N. Salaman; William Glynn Burton (1985). The History and Social Influence of the Potato. Cambridge UP. p. xi.

- ↑ Nunn, Nathan; Qian, Nancy (2011). "The Potato's Contribution to Population and Urbanization: Evidence from a Historical Experiment" (PDF). Quarterly Journal of Economics. 126 (2): 593–650. doi:10.1093/qje/qjr009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 July 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ↑ John Michael Francis, Iberia and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History : a Multidisciplinary Encyclopedia (2005) p. 867

- ↑ John Crowley, et al. Atlas of the Great Irish Famine (2012)

- ↑ Renee Marton, Rice: A Global History (2014).

- ↑ Michael Blake, Maize for the Gods: Unearthing the 9,000-Year History of Corn (2015).

- ↑ Anthony John Heaton Latham, "From competition to constraint: The international rice trade in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries." Business and economic history (1988): 91-102. in JSTOR

- ↑ Joan Thirsk, "L'agriculture en Angleterre et en France de 1600 à 1800: contacts, coïncidences et comparaisons." Histoire, économie et société (1999): 5-23. online

- ↑ Sidney Mintz, Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History (1985).

- ↑ Lizzie Collingham, Taste of War: World War II and the Battle for Food (2013) pp 18-19, 516.

- ↑ Fernando Collantes, "Nutritional transitions and the food system: expensive milk, selective lactophiles and diet change in Spain, 1950-65." Historia Agraria 73 (2017) pp 119-147 in Spanish.

- ↑ Katherine Leonard Turner (2014). How the Other Half Ate: A History of Working-Class Meals at the Turn of the Century. pp. 56, 142.

- ↑ Belinda J. Davis, Home Fires Burning: Food, Politics, and Everyday Life in World War I Berlin (2000).

- ↑ Richard Perren, "Farmers and consumers under strain: Allied meat supplies in the First World War." Agricultural History Review (2005): 212-228.

- ↑ Frank M. Surface and Raymond L. Bland, American Food in the World War and Reconstruction Period: 1914 to 1924 (1931). online

- ↑ Robert Graves and Alan Hodge, The Long Week-End: A Social History of Great Britain 1918–1939 (1940) pp. 175–176.

- ↑ Collingham, Taste of War: World War II and the Battle for Food (2013)

- ↑ Andrew Godley, "The emergence of agribusiness in Europe and the development of the Western European broiler chicken industry, 1945 to 1973." Agricultural History Review 62.2 (2014): 315-336.

- ↑ Hazell, Peter B.R. (2009). The Asian Green Revolution. IFPRI Discussion Paper. Intl Food Policy Res Inst. GGKEY:HS2UT4LADZD.

- ↑ Farmer, B. H. (1986). "Perspectives on the 'Green Revolution'in South Asia". Modern Asian Studies. 20 (01): 175–199. doi:10.1017/s0026749x00013627.

Further reading

- Collingham, Lizzie. Taste of War: World War II and the Battle for Food (2013)

- Gremillion, Kristen J. Ancestral Appetites: Food in Prehistory (Cambridge UP, 2011) 188 pages; explores the processes of dietary adaptation in prehistory that contributed to the diversity of global foodways.

- Grew, Raymond. Food in Global History, Westview Press, 2000

- Heiser Charles B. Seed to civilisation. The story of food (Harvard UP, 1990)

- Kiple, Kenneth F. and Kriemhild Coneè Ornelas,eds. The Cambridge World History of Food, (2 vol, 2000).

- Katz, Solomon ed. The Encyclopedia of Food and Culture (Scribner, 2003)

- Lacey, Richard. Hard to swallow: a brief history of food (1994) online free

- Mintz, Sidney. Tasting Food, Tasting Freedom: Excursions into Eating, Power, and the Past, (1997).

- Nestle, Marion. Food Politics: How the Food Industry Influences Nutrition and Health (2nd ed 2007).

- Parasecoli, Fabio & Peter Scholliers, eds. A Cultural History of Food, 6 volumes (Berg Publishers, 2012)

- Pilcher, Jeffrey M. ed. The Oxford Handbook of Food History (2017). Online review

- Pilcher, Jeffrey M. Food in World History (2017) advanced survey

- Ritchie, Carson I.A. Food in civilization: how history has been affected by human tastes (1981) online free

Foods and meals

- Anderson, Heather Arndt. Breakfast: A History (2014) 238pp

- Blake, Michael. Maize for the Gods: Unearthing the 9,000-Year History of Corn (2015).

- Elias, Megan. Lunch: A History (2014) 204pp

- Kindstedt, Paul. Cheese and Culture: A History of Cheese and its Place in Western Civilization (2012)

- Kurlansky, Mark. Milk!: A 10,000-Year Food Fracas (2018). excerpt

- Kurlansky, Mark. Salt: A World History (2003) excerpt

- Mintz, Sidney. Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History (1986)

- Pettigrew, Jane, and Bruce Richardson. A Social History of Tea: Tea's Influence on Commerce, Culture & Community (2015).

- Reader, John. Propitious Esculent: The Potato in World History (2008), 315pp a standard scholarly history

- Salaman, R.N. The history and social influence of the potato (1949)

- Valenze, Deborah,. Milk: A Local and Global History (Yale UP, 2012)

Historiography

- Claflin, Kyri and Peter Scholliers, eds. Writing Food History, a Global Perspective (Berg, 2012)

- Duffett, Rachel, and Ina Zweiniger-Bargielowska, eds. Food and War in Twentieth Century Europe (2011) excerpt

- Pilcher, Jeffrey M. "The embodied imagination in recent writings on food history." American Historical Review 121#3 (2016): 861-887.

- Pilcher, Jeffrey M., ed. Food History: Critical and Primary Sources (2015) 4 vol; reprints 76 primary and secondary sources.

- Scholliers, Peter. " Twenty-five Years of Studying un Phénomène Social Total: Food History Writing on Europe in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries," Food, Culture & Society: An International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research (2007) 10#3 pp 449-471 https://doi.org/10.2752/155280107X239881

Asia

- Achaya, Kongandra Thammu. A historical dictionary of Indian food (New Delhi: Oxford UP, 1998).

- Cheung, Sidney, and David Y.H. Wu. The globalisation of Chinese food (Routledge, 2014).

- Chung, Hae Kyung, et al. "Understanding Korean food culture from Korean paintings." Journal of Ethnic Foods 3#1 (2016): 42-50.

- Cwiertka, Katarzyna Joanna. Modern Japanese cuisine: Food, power and national identity (Reaktion Books, 2006).

- Kim, Soon Hee, et al. "Korean diet: characteristics and historical background." Journal of Ethnic Foods 3.1 (2016): 26-31.

- Kushner, Barak. Slurp! a Social and Culinary History of Ramen: Japan's Favorite Noodle Soup (2014) a scholarly cultural history over 1000 years

- Simoons, Frederick J. Food in China: a cultural and historical inquiry (2014).

Europe

- Gentilcore, David. Food and Health in Early Modern Europe: Diet, Medicine and Society, 1450–1800 (Bloomsbury, 2016)

- Goldman, Wendy Z. and Donald Filtzer, eds. Food Provisioning in the Soviet Union during World War II (2015)

- Roll, Eric. The Combined Food Board. A study in wartime international planning (1956), on World War II

- Scarpellini, Emanuela. Food and Foodways in Italy from 1861 to the Present (2014)

Great Britain

- Addyman, Mary et al. eds. Food, Drink, and the Written Word in Britain, 1820–1945 (Taylor & Francis, 2017).

- Brears, P. Cooking and Dining in Medieval England (2008)

- Burnett, John. Plenty and want: a social history of diet in England from 1815 to the present day (2nd ed. 1979). A standard scholarly history.

- Collins, E.J.T. "Dietary change and cereal consumption in Britain in the nineteenth century." Agricultural History Review (1975) 23#2, 97-115.

- Gazeley, I. and Newell, A. "Urban working-class food consumption and nutrition in Britain in 1904" Economic History Review. (2014). http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ehr.12065/pdf.

- Harris, Bernard, Roderick Floud, and Sok Chul Hong. "How many calories? Food availability in England and Wales in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries". Research in economic history. (2015). 111-191.

- Hartley, Dorothy. Food In England: A complete guide to the food that makes us who we are (Hachette UK, 2014).

- Meredith, D. and Oxley, D. "Food and fodder: feeding England, 1700-1900." Past and Present (2014). (2014). 222:163-214.

- Oddy, D. " Food, drink and nutrition" in F.M.L. Thompson, ed., The Cambridge social history of Britain, 1750-1950. Volume 2. People and their environment (1990). pp. 2:251-78.

- Otter, Chris. "The British Nutrition Transition and its Histories", History Compass 10#11 (2012): pp. 812-825, [DOI]: 10.1111/hic3.12001

- Panayi, Panikos. Spicing Up Britain: The Multicultural History of British Food (2010)

- Spencer, Colin. British Food: An Extraordinary Thousand Years of History (2007).

- Woolgar. C.N. The Culture of Food in England, 1200–1500 (2016). 260 pp.,

United States

- Pendergrast, Mark. For God, Country, and Coca-Cola: The Definitive History of the Great American Soft Drink and the Company That Makes It (2013)

- Shapiro, Laura. Something From the Oven: Reinventing Dinner in 1950s America, Viking Adult 2004, ISBN 0-670-87154-0

- Smith, Andrew F. ed. The Oxford companion to American food and drink (2007)

- Veit, Helen Zoe, ed. Food in the Civil War Era: The North (Michigan State University Press, 2014)

- Veit, Helen Zoe. Modern Food, Moral Food: Self-Control, Science, and the Rise of Modern American Eating in the Early Twentieth Century (University of North Carolina Press, 2013)

- Wallach, Jennifer Jensen. How America Eats: A social history of U.S. food and culture (2014) 256256pp

- Williams, Elizabeth M. New Orleans: A Food Biography (AltaMira Press, 2012).

Journals

- Food and Foodways. Explorations in the History and Culture of Human Nourishment

- Food, Culture and Society: An International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research

- Food & History, multilingual scientific journal about the history and culture of food published by the (IEHCA)

Other languages

- Montanari, Massimo, Il mondo in cucina (The world in the kitchen). Laterza, 2002 ASIN: B0055J686G

- Mintalová - Zubercová, Zora: Všetko okolo stola I.(All around the table I.), Vydavateľstvo Matice slovenskej, 2009, ISBN 978-80-89208-94-4

External links

- Getting Started in Food History

- University of Houston Digital Library: 1850-1860's Hotel and Restaurant Menu Collection images

- : FOST: Social & Cultural Food Studies (VUB's research unit in food history)

- Italian Food History Blog

- Spanish Food History Articles: 27 most relevant products and Timeline by Enrique García Ballesteros

- "Culinary History". NYPL Recommendations: Best of the Web. USA: New York Public Library.

- Explained With Maps - History of World Food (Documentary Video)