History of football in England

According to FIFA, the world governing body of football, the contemporary history of the game began in 1863 in England, when rugby football and association football "branched off on their different courses" and the English Football Association (the FA) was formed as the sport's first governing body.[1] Until the 19th century, football had been played in various forms using a multiplicity of rules under the general heading of "folk football". From about the 1820s, efforts were made at public schools and at the University of Cambridge to unify the rules. The split into two codes was caused by the issue of handling the ball.

The world's oldest football clubs were founded in England from 1857 and, in the 1871–72 season, the FA Cup was founded as the world's first organised competition. The first international match took place in November 1872 when England travelled to Glasgow to play Scotland. The quality of Scottish players was such that northern English clubs began offering them professional terms to move south. At first, the FA was strongly opposed to professionalism and that gave rise to a bitter dispute from 1880 until the FA relented and formally legitimised professionalism in 1885. A shortage of competitive matches led to the formation of the Football League by twelve professional clubs in 1888 and the domestic game has ever since then been based on the foundation of league and cup football.

The competitiveness of matches involving professional teams generated widespread interest, especially amongst the working class. Attendances increased significantly through the 1890s and the clubs had to build larger grounds to accommodate them. Typical ground construction was mostly terracing for standing spectators with limited seating provided in a grandstand built centrally alongside one of the pitch touchlines. Through media coverage, football became a main talking point among the population and had overtaken cricket as England's national sport by the early 20th century. The size of the Football League increased from the original twelve clubs in 1888 to 92 in 1950. The clubs were organised by team merit in four divisions with promotion and relegation at the end of each season. Internationally, England hosted and won the 1966 FIFA World Cup but has otherwise been among the also-rans in global terms. English clubs have been a strong presence in European competition with several teams, especially Liverpool and Manchester United, winning the major continental trophies.

The sport was beset by hooliganism from the 1960s to the 1980s and this, in conjunction with the impact of rising unemployment, caused a fall in attendances and revenue which plunged several clubs into financial crisis. Following three major stadium disasters in the 1980s, the Taylor Report was commissioned and this resulted in all-seater stadia becoming mandatory for clubs in the top-level divisions. In 1992, the Premier League was founded and its members negotiated a lucrative deal for live television coverage with Sky Sports. Television and marketing revived national interest in the sport and the leading clubs became major financial operations. As the 21st century began, the top players and managers were being paid over £100,000 a week and record-breaking transfer fees were frequently paid.

Early football

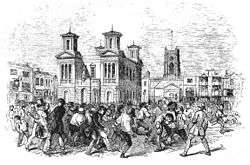

All modern forms of football have roots in the "folk football" of pre-industrial English society.[2] This generic form of football was for centuries a chaotic pastime played not so much by teams as by mobs. It was essentially a public holiday event with Shrove Tuesday in particular a traditional day for games across the country. It is generally thought that the games were "free-for-alls" with no holds barred and extremely violent. As for kicking and handling of the ball, it is certain that both means of moving the ball towards the goals were in use.[3] Little is known about football until the nineteenth century and the few surviving references are mostly about attempts at various times to ban it. The FIFA history says "there was scarcely any progress at all in the development of football for hundreds of years but, although it was persistently forbidden, it was never completely suppressed".[4]

Early references (14th to 18th centuries)

The earliest reference to football is in a 1314 decree issued by the Lord Mayor of London, Nicholas de Farndone, on behalf of King Edward II. Originally written in Norman French, a translation of the decree includes: "for as much as there is great noise in the city caused by hustling over large footballs in the fields of the public, from which many evils might arise that God forbid: we command and forbid on behalf of the King, on pain of imprisonment, such game to be used in the city in the future".[5] The earliest known reference to football that was written in English is a 1409 proclamation issued by King Henry IV. It imposed a ban on the levying of money for "foteball".[6] It was specific to London, but it is not clear if payments had been claimed from players or spectators or both. The following year, Henry IV imposed fines of 20 shillings on certain mayors and bailiffs who had allowed football and other "misdemeanours" to occur in their towns. This is the earliest documentary evidence of football being played throughout England.[7]

At the end of the sixteenth century, the game was still rough and unsophisticated but, in 1581, the scholar and headmaster Richard Mulcaster provided the earliest account of football as a team sport. He insisted that the game had "a positive educational value as it promoted health and strength". He suggested that it would improve if there were a limited number of participants per team and a referee in full control of proceedings.[4] Until the time of the English Civil War and the Commonwealth in the mid-17th century, opposition to football was mainly due to the public disturbance it allegedly caused. In 1608, for instance, it was banned in Manchester because of broken windows. The Puritans objected to it for a different reason. In their view, it was a "frivolous amusement", as were the theatre and several other sports. The big issue in the Puritan mindset was "violation of the Sabbath" and, once in power, they were able to impose a ban on Sunday entertainment which, in the case of sport, still prevailed for 300 years after the Restoration. Folk football was still played on weekdays, though, especially on holidays. It continued to be disorganised and violent. Despite Mulcaster's proposals, matches involved an indefinite number of players and sometimes whole villages were ranged against each other on a playing area that encompassed fields and streets.[4]

There is mention of football being played at Cambridge University in 1710. A letter from a certain Dr Bentley to the Bishop of Ely on the subject of university statutes includes a complaint about students being "perfectly at Liberty to be absent from Grace", in order to play football (referred to as "Foot-Ball") or cricket, and not being punished for their conduct as prescribed in the statutes.[8] It was at Cambridge University that the first rules of association football were drafted in the nineteenth century. In the meantime, folk football continued to be played according to local rules and customs.[3]

Nature of folk football

More is known about folk football through the 18th and 19th centuries. It was essentially a game for large numbers played over wide distances with goals that were as much as three miles apart, as at Ashbourne. At Whitehaven, the goals were a harbour wall and a wall outside the town. Matches in Derby involved about a thousand players. In all cases, the object of the exercise was to drive a ball of varying size and shape, often a pig's bladder, to a goal. Generally, the ball could be kicked, thrown or carried but it is believed there were some places at which only kicking was allowed. Whatever rules may have been agreed beforehand, there is no doubt at all that folk football was extremely violent, even when relatively well organised. One form of kicking that was common was "shinning", the term for kicking another player's legs, and it was legal even if the ball was hundreds of yards away.[2]

Folk football was essentially rural and matches tended to coincide with country fairs. Change was brought about by industrialisation and the growth of towns as people moved away from the country. The very idea of a game taking several hours over huge areas ran counter to "the discipline, order and organisation necessary for urban capitalism".[9] In 1801, a survey of British sports by Joseph Strutt described football as being "formerly much in vogue among the common people of England".[10] Although Strutt claimed that folk football was in disrepute and was "but little practised", there is no doubt that many games continued well into the nineteenth century before codification took effect.[11]

Codification (1801 to 1891)

Public school football

As the 19th century began, football became increasingly significant in the public schools because it was well suited to the ideals of the "Muscular Christianity" cult. It was, like cricket, perceived to be a "character-building" sport.[12] The trailblazer was Rugby School where the boys began playing the game around 1800, almost certainly inspired by the annual New Year's Eve game played by the people of Rugby, Warwickshire, through the 18th century.[12] The public schools sought to toughen their pupils so that they were fit to rule the British Empire. The policy was in response to widespread belief that past empires had fallen because the ruling class became soft.[12] At Rugby, pupils were encouraged to adopt shinning as a means of toughening up and they renamed the practice "hacking". It became something of an obsession, along with cold showers and punishing cross-country runs (cricket supposedly taught them how to be gentlemen).[13] Hacking was an important issue when the "handling game" split from the "dribbling game" later in the century.[13]

By the 1820s, other public schools began to devise their own versions of football, rules of which were verbally agreed and handed down over many years. Each school (e.g., Eton, Harrow and Winchester) had its own variations. Albert Pell, a former Rugby pupil who went to Cambridge University in 1839, began organising football matches there but, because of the different school variations, a compromise set of rules had to be found.[14] By 1843, a set of rules is believed to have been in existence at Eton which allowed handling of the ball to control it, but not running with it in the hand and not passing it by hand. The first known 11–a–side games took place at Eton where the "dribbling game" was popular. The written version of Rugby School Football Rules in 1845 allowed the ball to be carried and passed by hand. The Rugby rules are the earliest that are definitely known to have been written and were a major step in the evolution of Rugby League and Rugby Union.[15]

Eton introduced referees and linesmen, who were at that time called umpires. In 1847, another set of public school rules was created at Harrow which, like Eton, played the "dribbling game". Winchester had yet another version of the game.[16] The original Cambridge University Rules were written in 1848 by students who were still confused by different rules operating at the various schools. This was the first attempt at codifying the rules of association football (i.e., the "dribbling" game) as distinct from rugby football. Unfortunately, no copy of the original Cambridge Rules has survived. The essential difference in the two codes was always that association football did not allow a player to run with the ball in his hands or pass it by hand to a colleague, though players were allowed to touch and control the ball by hand.[16]

Sheffield, Cambridge and FA rules

In the winter of 1855–56, players of Sheffield Cricket Club organised informal football matches to help them retain fitness.[17] On 24 October 1857, they formally created Sheffield Football Club which is now recognised as the world's oldest association football club.[18] On 21 October 1858, at the club's first annual general meeting, the club drafted the Sheffield Rules for use in its matches. Hacking was outlawed but the "fair catch" was allowed, providing the player did not hold onto the ball.[19] Just over a year later, in January 1860, the rules were upgraded to outlaw handling.[20] On 26 December 1860, the world's first inter-club match took place when Sheffield defeated newly-formed Hallam F.C. at Sandygate Road, Hallam's ground.[21] In 1862, an impromptu team formed in Nottingham is understood to have been the original Notts County, which was formally constituted in December 1864 and is the oldest professional association football club in the world.[22] In 1867, the Sheffield and Hallam clubs formed the Sheffield Football Association, which is the oldest County FA. Its members used the Sheffield Rules until 1878 when they agreed to adopt the FA rules.

In October 1863, a revision of the Cambridge Rules was published. This was shortly before a meeting on Monday, 26 October, of twelve clubs and schools at the Freemasons' Tavern on Great Queen Street in London. Eleven of them agreed to form the Football Association (the FA).[16][23] One of them was Blackheath. Sheffield did not officially attend the meeting, but they sent observers and, in November, decided to join the FA. Sheffield immediately petitioned the FA to adopt the Sheffield Rules and the FA debated the subject at a series of meetings over the next six weeks. Sheffield were strongly opposed to hacking and running with the ball, both of which they condemned as "directly opposed to football". The FA voted to adopt parts of both the Cambridge and Sheffield rules. Hacking was outlawed and this caused Blackheath to quit the FA. Running with the ball in hand was also banned but players could still make the "fair catch" to earn a free kick.[24] Blackheath's resignation led directly to the formation of the Rugby Football Union in 1871.

Impact of rule changes (1863 to 1891)

Among other laws in 1863 were the absence of a crossbar, enabling goals to be scored regardless of how high the ball was. There was an offside rule, which originated at Sheffield earlier in 1863, that any player ahead of the kicker was offside (this is still the case in rugby). The throw-in had to be done at right angles to the touchline (like a rugby lineout), except that there was no touchline then with flags marking the boundaries of play. There was no goalkeeper, no referee, no punishment for infringement, no pitch markings, no half-time, no rules about number of players or duration of match. All told, it was a totally different ball game.

Over the years, the laws changed and football gradually acquired the features that are taken for granted today. The game opened up in 1866 when the offside rule was amended to the three-player ruling whereby a player was onside if there were three opponents between him and the goal. Under the 1863 offside rule, any attacking player ahead of the ball was offside and this restricted attacking play to dribbling or scrimmaging, as in rugby, or to "kick and rush", as in mob football.[25] After the three-player rule was introduced, an attacking player could pass the ball forward to a team-mate ahead of him and this allowed the passing game to develop.[26] In 1874, Charles W. Alcock coined the term "combination game" for a style of play that was based on teamwork and co-operation, largely achieved by passing the ball instead of dribbling it. Noted early exponents of the style were Royal Engineers A.F.C. (founded in 1863) and Glasgow-based Queen's Park F.C. (founded in 1867).[27]

Also in 1866, the fair catch was prohibited and the tape between goalposts was introduced to limit the height of the goal. The wooden crossbar was allowed as an optional alternative to tape in 1875. In 1883, it was ruled that the goal must be constructed entirely of wood and the tape option was removed. In the same year, the touchline was introduced in place of the flag markers.

Arguably the most significant change of law ever was the ban in 1870 on all forms of handling, which meant that the ball in play could only be kicked or headed (the ball is technically out of play while a throw-in is completed). In the following year, the goalkeeper was introduced and was allowed to handle the ball "for the protection of his goal". When it was ruled in 1877 that the throw-in could go in any direction, the Sheffield FA clubs agreed to abandon their rules and adopt the FA version.

Until 1891, adjudication was done by two umpires, one per team and both off the field. Captains attempted to settle disputes onfield but appeals could be made to the umpires. That could cause long delays. The referee, as such, was essentially a timekeeper but could be called upon to arbitrate if the umpires were unable to agree. In 1891, following a suggestion made by the Irish FA, the referee was introduced onto the field and was given powers of dismissal and awarding penalties and free kicks. The two umpires became the linesmen.[26]

Competitive, international and professional football (1871 to 1890)

On 20 July 1871, in the offices of The Sportsman newspaper, the FA secretary Charles Alcock proposed to his committee that "it is desirable that a Challenge Cup should be established in connection with the Association for which all clubs belonging to the Association should be invited to compete".[28] The inaugural FA Cup competition began with four matches played on 11 November 1871. Known originally as the "Football Association Challenge Cup", it is the sport's oldest major competition worldwide. All the teams were amateur and mainly from the London area. The first FA Cup Final was held at Kennington Oval on 16 March 1872 and Wanderers (founded in 1859) became the first winners by defeating Royal Engineers 1–0 with a goal scored by Morton Betts. Wanderers retained the trophy the following year and went on to win it five times in all.

International football began in 1872 when the England national team travelled to Glasgow to play the Scotland national team in the first-ever official international match. It was played on 30 November 1872 at Hamilton Crescent, the West of Scotland Cricket Club's ground in the Partick area of Glasgow. It ended in a 0–0 draw and was watched by 4,000 spectators.[29] At the time, there was no Scottish Football Association and the Scottish team was organised by Queen's Park F.C., who were members of the FA. The Scottish FA was officially founded on 13 March 1873. There had been earlier matches in London between teams called England and Scotland but those were not official internationals (i.e., not recognised by FIFA) because the Scottish teams consisted of London-based Scottish expatriates only.

The issue of professionalism arose in 1880 when a dispute began between the FA and Bolton Wanderers (founded in 1874), who had offered professional terms to Scottish players. The subject remained a heated one through the 1880s, directly or indirectly involving many other clubs besides Bolton. Their neighbours, Blackburn Rovers (founded in 1875) and Darwen (founded in 1870) had also signed Scottish players professionally. The FA espoused the ideal of so–called "amateurism" promoted by the likes of Corinthian F.C. from whom the phrase “Corinthian Spirit” came into being.[30] There were constant arguments about broken–time payments, out–of–pocket expenses and what amounted to actual wages. Despite its convictions, the FA had no objection to professional clubs playing in the FA Cup and this may have been a tacit acknowledgement that the growth of professionalism was inevitable, as had long been the case in cricket. Blackburn Rovers established the predominance of professionalism by winning the FA Cup in three successive seasons from 1884 to 1886 and the FA formally legitimised professionalism in 1885.

A key issue facing the professional clubs was the lack of competitive matches. This was especially so for teams that had been knocked out of the FA Cup. It was self–evident that crowds for friendly fixtures were much lower and of course this meant a reduction in revenue and consequent struggle to pay wages. Aston Villa’s Scottish director William McGregor sought a solution by asking the other professional clubs to arrange annual home and away fixtures on a competitive basis, with points to be awarded for winning and drawing. Following a conference between club directors on 23 March 1888, the English Football League was founded on 17 April 1888 as one division of 12 clubs: Accrington (founded in 1876; folded in 1896), Aston Villa (founded in 1874), Blackburn Rovers, Bolton Wanderers, Burnley (founded in 1882), Derby County (founded in 1884), Everton (founded in 1878), Notts County, Preston North End (founded in 1880), Stoke F.C. (founded in 1863; became Stoke City in 1925), West Bromwich Albion (founded in 1878) and Wolverhampton Wanderers (founded in 1877; always commonly known as "Wolves"). Six of the clubs were in Lancashire and six in the Midlands so, at this time, there were none from Yorkshire or the north-east or anywhere south of Birmingham. 1888–89 was the Football League’s inaugural season and Preston North End earned the nickname of “Invincibles” by going through the entire 22–match league competition unbeaten. They also won the FA Cup and so recorded the world's first “double”. Preston retained their league title in 1889–90 and Blackburn won the FA Cup.

Some of English football's most famous venues had been established by 1890. Bramall Lane, home of Sheffield United who were founded in 1889, is the world's oldest football stadium which is still in use a professional match venue. It opened on 30 April 1855 as a cricket ground and first hosted football in 1862. Deepdale, Preston's home ground which opened on 5 October 1878, is the world's oldest football stadium which has been in continuous use by a top-class club. Turf Moor, Burnley's ground, has been their home since 17 February 1883. Anfield opened on 28 September 1884 when the home team was Everton (they moved to Goodison Park in 1892 after a dispute about their lease and Liverpool F.C. was founded on 3 June 1892 to occupy the vacant stadium). Wolves played their first match at Molineux Stadium on 7 September 1889. Blackburn moved to Ewood Park in 1890.

Overview of football from 1889

In 1889, the Football Alliance was founded as a rival to the Football League. It was short–lived and collapsed in 1892 when the Football League expanded. The league's membership doubled from 14 to 28 clubs with divisions introduced for the first time. The original Football League became the new First Division, expanded to 16 teams, and the new Second Division was formed with 12 teams. League football became increasingly popular, especially with the working class, and large stadiums were built to accommodate huge crowds who were mainly packed onto terraces. Competitive football was suspended through World War I and both Football League divisions were expanded to 22 teams when it recommenced in 1919. In 1920, there was a greater expansion with the creation of the original Third Division for another 22 clubs. In 1921, another twenty clubs were admitted to the league and the Third Division was split into North and South sections. Football was again suspended during World War II. It was possible to organise an FA Cup competition in 1945–46 but league football did not restart until 1946–47. In 1950, the Football League reached its current size of 92 clubs when the two Third Division sections were increased to 24 clubs each. In 1958, the 48 Third Division clubs were reorganised nationally on current merit. The top twelve in each of the north and south sections formed a new Third Division while the other 24 formed the new Fourth Division.

During the 1960s, hooliganism emerged as a problem at certain clubs and became widespread through the 1970s and 1980s. Matters came to a head in 1985 when the Heysel Stadium disaster occurred. English hooligans ran amok in a decrepit stadium before the 1985 European Cup final and caused the deaths of 39 Juventus fans. As a result, English teams were banned from European football for five years (six years in the case of Liverpool). Falling attendances were evident throughout the league during these decades. Hooliganism was one cause of this but the main one was unemployment, especially in the north of England. Many clubs faced the possibilities of bankruptcy and closure. The Hillsborough disaster in 1989 was caused by bad policing, an outdated stadium and inappropriate security fences. The government stepped in and ordered an enquiry into the state of football. The outcome was the Taylor Report which enforced the conversion of all top-level grounds to all-seater.

In 1992, the First Division became the FA Premier League and it secured a lucrative contract with Sky Sports for exclusive live TV rights. The clubs received huge TV revenues and wages rose to over £100,000 a week for the leading players and managers. Transfer records were broken on a frequent basis as the clubs grew ever wealthier and the sport's popularity increased. One aspect of the financial boom was an influx of overseas players, including many world-class internationals. The sport has maintained this level of success into the 21st century and BT Sport has become a second major source of TV revenue.

1891 to 1918

In 1891 Liverpool engineer John Alexander Brodie invented the football net.

In 1892, a new Division Two was added, taking in more clubs from around the country; Woolwich Arsenal became the first League club from the capital in 1893; they were also joined by Liverpool the same year. By 1898, both divisions had been expanded to eighteen clubs. Other rival leagues on a local basis were being eclipsed by the Football League, though both the Northern League and the Southern League - who provided the only ever non-league FA Cup winners Tottenham Hotspur in 1901 - remained competitors in the pre-World War I era.

At the turn of the 20th century, clubs from Sheffield were particularly successful, with Sheffield United winning a title and two FA Cups, as well as losing to Tottenham in the 1901 final; meanwhile The Wednesday (later Sheffield Wednesday) won two titles and two FA Cups, despite being relegated in 1899 they were promoted the following year. Clubs in Tyne and Wear were also at the forefront; Sunderland had won four titles between 1892 and 1902, and in the following decade Newcastle United won the title three times, in 1905, 1907 and 1909, and reached five FA Cup finals in seven years between 1905 and 1911, winning just the one, however. In addition Bury managed a 6–0 win over Derby County in the 1903 FA Cup Final, a record scoreline that stands to this day.

During the first decade of the 20th century, Manchester City looked to be emerging as England's top side after winning the FA Cup for the first time in 1904, but it was soon revealed that the club had been involved in financial irregularities, which included paying £6 or £7 a week in wages to players when the national wage limit was £4 per week. The authorities were furious and rebuked the club, dismissing five of its directors and banning four of its players from ever turning out for the club again.

Instead, it was City's neighbours United who were the more successful side during the early 20th century, helped by the acquisition of a number of former City players, including the talented Welsh winger Billy Meredith. They reached the First Division in 1906 and were crowned league champions two years later. The following year, 1909, they won the FA Cup and they added another league championship in 1911. A decline set in, however, and there would be no major trophies for the red half of Manchester for the next 37 years. Further domination of the game by clubs from the north-west came in the shape of Liverpool, who won two league titles in 1901 and 1906, and Everton, who won the FA Cup in 1906. And in the run-up to World War I, Blackburn Rovers recorded two league titles 1912 and 1914, before hostilities meant professional football was suspended. Oldham Athletic briefly appeared to be emerging as a force in English football at this time, emerging as title challengers in the 1914-15 season before finishing runners-up. However, after league football was resumed in 1919, the reshaped Oldham side failed to match their pre-war standards, and were relegated in 1923, not reclaiming their First Division status for 68 years.

Clubs from the South fared poorly in comparison, though in 1904 Woolwich Arsenal became the first club from London to be promoted to the First Division, while a slew of clubs from the capital joined the League (including Clapton Orient, Chelsea, Fulham and Tottenham Hotspur), making it a properly nationwide competition; both Chelsea and Spurs quickly gained promotion to the top flight as well. By 1921, Spurs had won two FA Cups, although Arsenal and Chelsea had still yet to win any silverware.

Woolwich Arsenal had struggled to attract high attendances even after promotion to the First Division, and so the club's owners decided to relocate from Plumstead, South London, to a new stadium in the Highbury area of North London in 1913. They were to play at this site for 93 years until relocating to the Emirates Stadium nearby in 2006.

On the international scene, the Home Nations continued to play each other, with Scotland the slightly more successful of the four. When the countries combined to play as Great Britain in the Olympic Games they were unbeatable, winning all three pre-World War I football gold medals. England played their first games against teams outside of the British Isles in 1908.

1919–1939: Inter-war years

From 1920 to 1923 the Football League expanded further, gaining a new Third Division (expanding quickly to Division Three South and Division Three North), with all leagues now containing 22 clubs, making 88 in total. In addition, in 1923 Wembley Stadium opened, and hosted its first Cup final, between Bolton Wanderers and West Ham United, known today as the "White Horse Final"; Bolton won 2–0.

During the interwar years, Arsenal and Everton were the two most dominant sides in English football, although Huddersfield Town did make history in 1926 by becoming the first team to complete a hat-trick of successive league titles. Arsenal would do the same in 1935. Manager Herbert Chapman was involved with both of these teams. He guided Huddersfield to the first two of their league titles before taking over at Arsenal, where he presided over the first two league titles, but he died just before the third consecutive title was clinched.

Everton had hit the headlines in 1928 by winning the league championship thanks largely to the record breaking 60 league goals of 21-year-old centre-forward Dixie Dean. He was helped by the new rules of the 1920s, including the allowing of goals from a corner kick, and the relaxing of the offside rule. Everton also won the league twice more, in 1932 and 1939, and the FA Cup in 1933. Their neighbours Liverpool had earlier won back-to-back titles in 1922 and 1923, but were unable to sustain this success. Arsenal were the most successful English club of the 1930s, winning a host of league titles and FA Cups with a team featuring players including Alex James, Eddie Hapgood, Joe Hulme, and Cliff Bastin.

Sheffield Wednesday were also successful during the 1930s, winning the 1929–30 title, the FA Cup in 1935 and finishing in the top three in all but one season in the period 1930–36. In addition, it was during this time that a Welsh side won the FA Cup for the only time; Cardiff City beating Arsenal 1–0 in the 1927 Final.

The 1930s saw the breakthrough of notable players including Stanley Matthews, who was first capped for England in 1934 when playing for Stoke City, and just before the outbreak of war, Tommy Lawton, who succeeded Dixie Dean in attack for Everton and England.

The national team remained strong, but lost their first game to a non-British Isles country in 1929 (against Spain in Madrid) and refused to compete in the first three World Cups, held once every four years from 1930. There was no World Cup in 1942 due to wartime hostilities, and although the war ended in 1945, there was not enough time or funding to organise a World Cup for 1946.

1945–1961: The end of English dominance

English football reconvened in the years following the end of World War II, when most clubs had closed down for a period, with the 1945–46 FA Cup, which saw the competition played over two legs to make up for a lack of league competition that season, although there had been regional wartime competitions and friendly matches during the hostilities. The first post-war trophy went to Derby County, who beat Charlton Athletic 4–1 in the final. The league restarted in the 1946–47 season, with the first title going to Liverpool. However, both Derby and Liverpool lost their First Division status during the 1950s, with Liverpool not returning until 1962 and Derby not until 1969.

In the immediate post-war years, Arsenal won another two titles and an FA Cup but after the second title win in 1953, began to fade considerably and would not win another trophy for nearly 20 years, although they did remain in the First Division throughout this time. However, three of their London rivals would enjoy major success over the next 15 years, with Chelsea, Tottenham Hotspur and West Ham United all winning major trophies.

Portsmouth were also successful in the early postwar years. Having won the FA Cup in the last season before the war, they won their first league title in 1949 and retained it a year later, but like Liverpool they were relegated by the time the decade was over.

Manchester United re-emerged as a footballing force under new manager Matt Busby. They won the FA Cup in 1948 and the league title in 1952, the club's first trophies since before the Great War. Key players in this team included Johnny Carey, Jack Rowley and Stan Pearson. Busby's next successful team was the "Busby Babes", so called as the players were all young, rising through the club's youth system, developed as one of England's finest teams ever, with the likes of Bobby Charlton, Dennis Viollet, Tommy Taylor and Duncan Edwards winning two further titles in 1956 and 1957. Manchester United also became the first English team to compete in the new European Cup, contested by champions of European domestic leagues, reaching the semi-finals in 1957 and 1958.

But the Munich air disaster on 6 February 1958 resulted in the deaths of eight players (including Taylor and Edwards) and ended the careers of two others, while Busby survived with serious injuries. He built a new United side with a mix of young players, Munich survivors and new signings, and five years later his rebuilding programme paid off with FA Cup glory.

The other dominant team of the era was Wolverhampton Wanderers. Wolves, who had previously spent most of the interwar period in the lower divisions, won three league titles and two FA Cups under manager Stan Cullis and captain Billy Wright. Other Midlands sides also enjoyed success after a barren period, including West Bromwich Albion's FA Cup win in 1954 (their first trophy in 23 years) and Aston Villa matching them with a Cup win in 1957 (their first in 37 years). In addition, in 1951 Tottenham Hotspur became the first team in English football to win the league title immediately after being promoted, and Chelsea won their first and only league title of the 20th century in 1955.

One of the most memorable matches of the era was when Blackpool beat Bolton Wanderers 4–3 in the 1953 FA Cup Final, in a match that came to be known as the "Matthews Final", for Blackpool's mercurial winger Stanley Matthews, even though it was Stan Mortensen who scored a hat-trick that day; it remains Blackpool's only major honour.

English football as a whole, however, began to suffer at this time, with tactical naivety setting in. The national team were humiliated at their first World Cup in 1950, famously losing to the USA 1–0. This was followed by two defeats in 1953 and 1954 to Hungary, who destroyed England 6-3 at home, the first time England had lost at home to a non-British Isles team, and 7–1 in Budapest, England's biggest ever defeat. The early European club competitions also went without much English success, with the FA initially unwilling to allow clubs to compete. No English team reached a European Cup final until 1968, which was the same year that England got their first Fairs Cup success; although English teams Birmingham City (twice) and a London XI had reached the first three finals of the competition in its formative days.

Great players who rose to prominence during the 1950s include Duncan Edwards, Tommy Taylor, Bobby Charlton, Denis Law, Bobby Robson, Norman Deeley, Peter Sillett, Danny Blanchflower, Denis Compton and Joe Mercer.

While Edwards and Taylor both lost their lives due to the Munich tragedy, many older players naturally reached the end of their illustrious careers at around the same time. These include Nat Lofthouse, Tom Finney, Billy Wright, Stan Mortensen, Bert Williams and Johnny Carey.

Managers who achieved glory in the first 15 years of postwar English football include Matt Busby, Tom Whittaker, Stan Cullis, Ted Drake and Stan Seymour.

1963–1971

The end of the 1950s had seen the beginning of the modernisation of English football, with the Divisions Three North and South becoming the national Division Three and Division Four in 1958. 1960 saw the introduction of the League Cup (with the first winners being Aston Villa), whilst Matt Busby built a new team for the 1960s starring Munich survivor Bobby Charlton, youth team product George Best and British record signing Denis Law. Meanwhile, successful sides of the 1950s like Wolves started to decline, with relegation eventually coming in 1965. The decade was also less successful for the likes of Blackpool and Bolton Wanderers, who had been among the top sides of the early postwar years.

It was Tottenham Hotspur who became the dominant force in English football in the early 1960s, winning the elusive double of the League and FA Cup in 1961, retaining the cup in 1962 and becoming the first British team to win a European trophy, after their 5–1 victory over Atlético Madrid in the 1963 UEFA Cup Winners' Cup final. The captain of this side was Danny Blanchflower, who retired in 1964, after which manager Bill Nicholson built a new side containing the likes of Jimmy Greaves and Terry Venables, which won the FA Cup in 1967.

Fellow London side West Ham United were also successful, with the England trio of Bobby Moore, Geoff Hurst and Martin Peters helping them win the 1964 FA Cup and the 1965 Cup Winners' Cup. All three would go on to play a key role in an even bigger success for their country.

The English national side showed signs of improving with Alf Ramsey taking over as head coach following a respectable quarter final appearance at the 1962 FIFA World Cup. Ramsey confidently predicted that at the next tournament, England would win the trophy, and they did just that.

The 1966 World Cup saw England win the World Cup in a controversial 4–2 victory over West Germany. The three goals scored by Geoff Hurst within 120 minutes, of which some are controversial, are the only hat trick to be achieved in a World Cup final to date. Bobby Moore was the captain on that day, whilst Munich air crash survivor Bobby Charlton also played. Moore's West Ham colleagues Geoff Hurst and Martin Peters scored that day. The World Cup as a whole was highly successful, with the successes of the North Korea team, the fouls of the Uruguay team, the skill of Eusébio and the famous quote They think it's all over ... it is now entering England's collective memory.

The period also saw the first English successes in European club football, begun with Manchester United's 4–1 European Cup victory over S.L. Benfica, and Leeds United's Inter-Cities Fairs Cup victory, both in 1968. The Fairs Cup (which was renamed the UEFA Cup in 1971) ended up being won by English clubs for six seasons in succession, with the 1972 final being held between two of them, Tottenham Hotspur and Wolverhampton Wanderers.

During this time, a number of different teams competed for league and cup success. Manchester City enjoyed success at the same time as their rivals United, winning the First Division title for only the second time in 1968, and the FA Cup the year after that, and a double of the Cup Winners' Cup and League Cup in 1970. Leeds' Fairs Cup success was no isolated effort; Don Revie's side also won a League Cup in 1968 and the league title the season after. Liverpool under Bill Shankly had won promotion in 1962 and soon after won the league title in 1964, and again in 1966, with an FA Cup in between; their neighbours Everton meanwhile had similar success, taking two league titles in 1963 and 1970, and the FA Cup in 1966.

Players who dominated the English scene during the 1960s include Bobby Moore, Geoff Hurst, Bobby Charlton, George Best, Denis Law, Jimmy Greaves, Francis Lee, Jeff Astle, Gordon Banks and Roger Hunt. With the exception of Best and Law, all of these players appeared for the England team, with six of them being in England's 1966 World Cup squad.

The decade also saw the illustrious careers of many famous older players drawing to a close. These include Danny Blanchflower, Harry Gregg, Dennis Viollet, Norman Deeley, Peter McParland, Noel Cantwell, Bert Trautmann, Jimmy Adamson, and the 50-year-old Stanley Matthews, who played his final game for Stoke City in February 1965.

Successful managers of the 1960s included Matt Busby, Bill Nicholson, Harry Catterick, Bill Shankly, Don Revie, Joe Mercer and Ron Greenwood.

The 1970s began with Everton as league champions, while Chelsea won their first ever FA Cup. A year later, Arsenal became the second club of the century to win the double. 1972 saw Derby County win the league title for the first time under the management of Brian Clough, while Leeds United continued to enjoy success as FA Cup winners and Stoke City lifted the League Cup to claim the first major trophy of their history.

The League Cup was shunned by a number of leading English clubs during the 1960s, before the Football League eventually made participation compulsory for all member clubs. The first winners were Aston Villa, still statistically the most successful club in English football at this point. Their local rivals Birmingham City won the third League Cup in 1963 - the first major trophy of their history. The 1962 winners, Norwich City, had yet to even play in the First Division. Established clubs including Chelsea and West Bromwich Albion won the League Cup during its early years, but it was won by Third Division clubs on two occasions, with Queen's Park Rangers winning the first one-match League Cup final at Wembley in 1967 (the first six finals had been played over two legs), and Swindon Town winning the trophy in 1969.

1972–1985: The rise of Liverpool

The 1970s was an odd decade in English football, with the national team disappointing but English clubs enjoying great success in European competitions. They failed to qualify for the 1974 and 1978 World Cups, and also missed out on qualification for the final stages of the European Championships in 1972 and 1976. English club sides, however, dominated on the continent. Altogether, in the 1970s, English clubs won eight European titles and lost out in four finals; whilst from 1977 to 1984 English clubs won seven out of eight European Cups.

London clubs had enjoyed a strong start to the decade, with Arsenal and Chelsea winning silverware, while West Ham United won their second FA Cup in 1975. Arsenal reached the FA Cup final three years in a row from 1978, but only had one win, also being beaten in a European final.

However, the dominant team in England in this period was Liverpool, winning league titles in 1973, 1976, 1977, 1979, 1980, 1982, 1983 and 1984. They also collected three European Cups, three FA Cups and four League Cups, under Shankly and his successor Bob Paisley, who retired as manager in 1983 to be succeeded by veteran coach Joe Fagan. Players such as Emlyn Hughes and Alan Hansen helped Liverpool have a solid and reliable side, whose skill and talent was supported by a strong work ethic and the famous "boot room" identity. Kevin Keegan was Liverpool's leading striker for much of the 1970s before being sold to HSV Hamburg in 1977 and being replaced by Kenny Dalglish. The midfield was boosted towards the end of the decade by the arrival of Graeme Souness, and the early 1980s spawned further new stars including high-scoring striker Ian Rush, talented midfielder Craig Johnston and skilful defender Steve Nicol.

The other notably successful teams of the era were Derby County, Nottingham Forest, Everton and Aston Villa. Derby, led by Brian Clough and then Dave Mackay, were the only team other than Liverpool to win the league more than once in the 1970s and also reached the semi-final of the European Cup in the 1972–73 season, though they faded rapidly towards the end of the decade, going down in 1980. Forest, led by Brian Clough (who had an infamous 44-day stint at Leeds United after resigning at Derby), took over at the City Ground in January 1975 when Forest were a struggling Second Division side; in 1977 he took them into the First Division and they won the league title a year later, followed by two successive European Cup triumphs and also adding two League Cups. Everton began the 1970s on a high note as league champions in 1970, but rarely featured in the race for the major trophies until they won the FA Cup under Howard Kendall in 1984. They added the league title and European Cup Winners' Cup a year later. Aston Villa had bounced back from relegation to the Third Division in 1970, winning promotion to the top flight in 1975 and a League Cup the same year, and again in 1977. They went on to win the 1981 league title and the year after won the European Cup, becoming the fourth English club to do so, beating Bayern Munich 1–0 in Rotterdam.

Between 1965 and 1974 Leeds had been the most consistent club side in English football, winning two league titles, as well as five runners-up places, had never finished outside the top four and had reached nine major finals, and 4 other semi-finals, as well as winning the FA cup in 1972, however this success would end with the departure of Don Revie for the England national team 1974, and apart from a final flurry in the 1975 European cup final, they won no more trophies and were relegated in 1982.

Other clubs did not fare as well in the 1970s; Manchester United began to decline after Matt Busby's retirement in 1969 and were relegated in 1974. However, they were promoted back the following season, and reached three cup finals in four years (1976, 1977 and 1979), though they only won the 1977 final. United went on to finish second twice during the 1980s and won two more FA Cup's in 1983 and 1985, but the league title continued to elude them - they had not won it since 1967.

On the other hand, their neighbours City struggled in the early 1980s after doing relatively well in the 1970s. They were FA Cup runners-up in 1981, but heavy spending on players who rarely lived up to their price tags did the club no favours and they were relegated in 1983 and again in 1987, reclaiming their First Division status after two seasons on both occasions, although it would be more than 20 years before they began to seriously compete among the leading English clubs again.

Meanwhile, Chelsea were also going through a turbulent time after winning the FA Cup in 1970 and the European Cup Winners' Cup in 1971. Financial problems and the loss of key players meant they spent most of 1970s and 1980s bouncing between the First and Second Divisions. In 1983, they only narrowly avoided relegation to the Third Division, but were promoted the following year.

Wolves, who had arguably been the best team of the 1950s and were still a reasonable force in 1980 (when they finished sixth and won the League Cup), suffered a spectacular decline which began in 1984 and ended in 1986 with three successive relegations that saw them in the Fourth Division for the first time. They were not alone in suffering a relegation hat-trick; Bristol City had completed the first such humiliation in 1982, though they were admittedly a far smaller club whose relegation in 1980 came after just four years in the top flight after an absence of 65 years.

Ipswich Town, managed by the former England forward Bobby Robson, re-emerged as a successful side in the 1970s, winning the FA Cup in 1978. They followed this with UEFA Cup glory in 1981 and were also league runners-up and FA Cup semi-finalists that year. They finished runners-up again in 1982, but Robson then departed to manage the England team and the successful side of the late 1970s and early 1980s was gradually broken up. With vast amounts of money being spent on upgrading their Portman Road stadium, there was very little money for the Suffolk club to spend on new players, and they were relegated in 1986.

Wolves were one of several once-great sides to endure a decline during the 1970s and early 1980s. Huddersfield Town (who complete the first league title hat-trick during the 1920s) were relegated from the First Division in 1971 and fell into the Fourth Division in 1975, not winning promotion until 1980. Portsmouth (league champions in 1949 and 1950) fell into the Fourth Division in 1978 as an almost bankrupt side, but climbed out of it in 1980 and within five years were looking capable of reaching the First Division for the first time since the 1950s. Derby County were league champions in 1972 and 1975, but a rapid decline saw them fall into the Second Division in 1980 and the Third Division in 1984, almost going out of business just before their second relegation. Burnley, league champions as recently as 1960, fell into the Fourth Division in 1985, and with the introduction of automatic relegation from the Football League, narrowly avoided relegation to the Football Conference (the highest division of non league football since its formation in 1979) in 1987.

The period was also marked by some surprise FA Cup wins by lower-division teams over top-flight sides; these included Sunderland (beating Leeds United in 1973), Southampton (beating Manchester United in 1976) and West Ham United (beating Arsenal in 1980). Bobby Robson's Ipswich Town were another successful smaller club, winning the FA Cup in 1978 and the UEFA Cup in 1981. They also came second in the league in 1981 and 1982.

During this period transfer fees began to rise rapidly as more money entered the game; Trevor Francis became Britain's first million-pound footballer in February 1979 when he signed for Nottingham Forest, whose full-back Viv Anderson had just become England's first black international player, a landmark which reflected the growing number of non-white players in the English game. In October 1981, Bryan Robson became England's first £1.5million footballer with his transfer from West Bromwich Albion to Manchester United.

However, hooliganism continued to blight English football throughout the 1970s and into the 1980s, contributing to a fall in attendances, accelerated by the recession of the early 1980s. This spelled financial problems for a number of clubs, particularly those who suffered a decline on the pitch as well. In the space of a few years, some of the most famous clubs in English football were faced with the threat of going out of business. These included Blackpool, Chelsea, Derby County, Middlesbrough and Wolverhampton Wanderers.

1979 saw the formation of the Football Conference. This was the first national league to develop below the Football League, and was the beginning of a formalisation of the English football pyramid. The first seven Conference champions failed to gain election to the Football League, but in 1986 it was decided that the following year's champions would be automatically promoted to the league to replace the Fourth Division's bottom side ...

The re-election system saw Cambridge United elected to the league in 1970, Hereford United in 1972, Wimbledon in 1977 and Wigan Athletic in 1978. Cambridge reached the Second Division in 1978 and were a competent side at this level for five seasons before a terrible decline saw them fall back into the Fourth Division in 1985, although they did enjoy a swift but brief revival in the early 1990s which took them to the brink of top division football.

Hereford reached the Second Division after just four years of league membership, only to endure back-to-back relegations which pushed them back into the Fourth Division in 1978.

Wimbledon's first two promotions from the Fourth Division ended in relegation after just one season, but by 1984 they had reached the Second Division and their biggest successes were yet to come.

After the dark days of the 1970s, the English national team began to recover slowly in the early 1980s. Ron Greenwood had succeeded Don Revie as England manager in the autumn of 1977, and took England to the European Championships in 1980 and the World Cup in 1982. He was succeeded by Bobby Robson in July 1982. England missed out on qualification for the 1984 European Championships, but the FA kept faith in Robson and he delivered qualification for the 1986 World Cup.

Players who dominated the English scene during the 1970s and early 1980s include Kevin Keegan, Kenny Dalglish, Graeme Souness, Peter Shilton, Bryan Robson, John Wark, Liam Brady, Steve Perryman, Glenn Hoddle and Alan Hansen.

Older players whose careers finished during this time include Bobby Moore, Bobby Charlton, George Best, Denis Law, Jimmy Greaves, Billy Bremner, Jack Charlton, Emlyn Hughes, Gordon Banks and Alex Stepney.

Successful managers of this era include Bill Shankly, Bob Paisley, Don Revie, John Lyall, Brian Clough, Ron Saunders, Ron Atkinson, Bobby Robson and Keith Burkinshaw.

1986–1991: The end of an era

During the 1970s and 1980s, the spectre of hooliganism had begun to haunt English football. The Heysel Stadium disaster was the epitome of this, with English hooligans mixing with poor policing and an old stadium to cause the deaths of 39 Juventus fans during the 1985 European Cup final. This led to English teams being banned from European football for five years, and Liverpool - the club involved - being banned for six. Attendances also suffered throughout the league, with hooliganism and the recession being seen as the key factors. Teams in the north of England, the region with some of the worst unemployment rates nationally, suffered a particularly sharp decline in attendances, which did their financial position no favours. Indeed, the mid 1980s saw two former title-winning sides from the north of England - Burnley and Preston North End - relegated to the Fourth Division for the first time, and then come very close to losing their league status completely. In 1986, Wolverhampton Wanderers became only the second team in English football to suffer three successive relegations, dropping into the Fourth Division for the first time as well, although they were saved from closure for the second time in four years by a new owner.

Even when English teams were re-admitted to European competitions, it was not until 1995 that they regained all of their lost places. And it took a while for English teams to re-establish themselves in Europe. Although Manchester United won the European Cup Winners' Cup in the first season after the ban was lifted, the European Cup was not won by an English club until 1999 – 15 years after the last triumph.

The Hillsborough disaster, which also involved Liverpool, though not related to hooliganism but caused by bad policing, an outdated stadium and anti-hooligan fences led to 96 deaths and more than 300 injuries at the FA Cup semi-final in April 1989. These two tragedies led to a modernisation of English football and English grounds by the mid-1990s. Efforts were made to remove hooligans from English football, whilst the Taylor Report led to the grounds of all top level clubs becoming all-seater.

Match attendances, which had been in decline since the late 1970s, were beginning to recover by the turn of end of the 1980s thanks to the improving image of football as well as the strengthened national economy and falling unemployment after the crises of the 1970s and the first half of the 1980s.

On the field, Liverpool's domination was coming to an end by 1991. One of the biggest success stories of this era was that of Wimbledon, who rose from the Fourth Division to the First in just four seasons, before finishing sixth in their inaugural season in the top flight and beating Liverpool 1–0 in the 1988 FA Cup final, one of the competition's biggest shocks. They had only joined the league in 1977. Another team to make an improbably quick rise from Fourth to First Divisions was Swansea City, who had climbed three divisions between 1977 and 1981. They finished sixth in their first top division campaign, but were relegated the following year and in 1986 fell back into the Fourth Division, having narrowly avoided going out of business. Watford had reached the First Division for the first time in 1982 and finished league runners-up in their first season at this level and were FA Cup runners-up a year later, but were relegated in 1988.

A number of other small clubs achieved success at this time. Charlton Athletic, who were forced to leave The Valley and ground-share with West Ham for safety reasons in 1985, won promotion to the First Division in 1986 after an exile of nearly 30 years. They defied the odds by surviving at this level for four seasons. Norwich City enjoyed even more success during this era. The Norfolk club went down to the Second Division in 1985 but that blow was cushioned by a League Cup triumph. They returned to the top flight a year later and finished fifth on their comeback, also coming fourth and reaching the FA Cup semi-finals in 1989, being in with a serious chance of winning the double with only a few weeks of the season remaining. They reached another FA Cup semi-final in 1992. Oxford United, who had only joined the Football League in 1962, reached the First Division in 1985 and lifted the League Cup the following season. They went back down again in 1988, the same year that Middlesbrough reached the First Division a mere two seasons after almost going out of business as a Third Division side. Luton Town, who began the latest of several spells as a First Division side in 1982, won the Football League Cup - their first major trophy - in 1988 at the expense of a much more fancied Arsenal side.

One fallen giant to enjoy something of a resurgence in this era was Derby County. They had been relegated to the Third Division in 1984, just nine years after being league champions, but back-to-back promotions saw them back in the First Division in 1987. They emerged as surprise title contenders in 1988–89 and finished fifth, only missing out on a UEFA Cup place due to the ban on English clubs in European competition. But Derby were unable to sustain their run of success, and went down to the Second Division in 1991.

After their three consecutive relegations and almost going out of business twice in four years, Wolverhampton Wanderers were beginning to recover by 1987. By 1989, they had won promotion to the Second Division almost single-handedly thanks to the goalscoring exploits of striker Steve Bull, who became the first English footballer to score 50 or more competitive goals in successive seasons, and one of the few Third Division players to be selected for the senior England team. Local businessman Jack Hayward took the club over in 1990, and declared his ambition to restore Wolves to the elite on English football.

Bolton Wanderers, four times FA Cup winners, were relegated to the Fourth Division in 1987, the same year that Sunderland fell into the Third Division for the first time in their history. Both teams, however, won promotion at the first attempt. Sunderland returned to the First Division in 1990 but went down after just one season.

Burnley's recovery was more steady; they did not climb out of the league's basement division until 1992 and did not reclaim their top flight status until 2009, only surviving for one season at this level.

With Liverpool's fortunes waning, George Graham's Arsenal emerged as a dominant force in the English game, winning the League Cup in 1987 and two league titles, in 1989 and 1991, the former being won in the final minute of the final game of the season against title rivals Liverpool, with young midfielder Michael Thomas scoring the crucial goal. Arsenal would go on to be the first side to pick up the Cup Double in 1993, and followed it with a Cup Winners' Cup the year after. The 1991 title triumph was achieved with just one defeat from 38 league games.

Arsenal's neighbours Tottenham were also successful, winning the FA Cup in 1990–91, with midfielder Paul Gascoigne proving the hero in the semi-finals against Arsenal before injuring himself in the final against Nottingham Forest. Tottenham bought Barcelona's high-scoring England striker Gary Lineker in 1989, and he continued his excellent form over three years at the club before leaving to finish his career in Japan.

Leeds had finally won promotion back to the top flight in 1990 and under Howard Wilkinson they won the 1991–92 league title. Wilkinson is still the most recent English manager to win the league championship. However, the departure of Eric Cantona to Manchester United, amongst other factors, meant they were unable to make a regular challenge for the title following the creation of the Premier League, although they did survive at this level for 12 seasons and achieved regular top five finishes.

Manchester United's six-year trophyless run had ended in 1983 when manager Ron Atkinson (appointed in 1981) guided them to FA Cup glory. They achieved another triumph two years later, but had still gone without a league title since 1967. 10 successive league wins at the start of the 1985–86 season suggested that the title was on its way back to Old Trafford, but United's form fell away as they finished fourth and Liverpool sealed the title. A terrible start to the 1986–87 season cost Atkinson his job in early November, when Alex Ferguson was recruited from Aberdeen. Ferguson strengthened the squad in the 1987 close season and the first stages of the new season and things were looking good as Ferguson's first full season as manager saw United finished second behind runaway champions Liverpool. Further signings after this improvement suggested that the title was even closer for United, but a series of injuries blighted the side and they finished 11th in 1989. United's wait for silverware ended in 1990 when they won their 7th FA Cup, and a year later they won the European Cup Winners' Cup, but it had now been well over 20 years since the league title had been United's.

Despite failure to qualify for Euro 1984 (the first major tournament since the appointment of Bobby Robson as manager), England continued to improve as the 1980s wore on, losing controversially to Argentina in the 1986 World Cup and unluckily on penalties to Germany in the semi-finals of the 1990 World Cup, eventually finishing fourth. This success for the national team, and the gradually improving grounds, helped to reinvigorate football's popularity. Attendances rose from the late 1980s and continued to do so as football moved into the business era.

However, the ban on English clubs in European competitions from 1985 to 1990 had led to many English-based players moving overseas. Manchester United striker Mark Hughes and Everton's top scorer Gary Lineker were sold to FC Barcelona in 1986, although both players were back in England by the decade's end, Hughes back at Old Trafford and Lineker playing for Tottenham. Ian Rush left Liverpool for Juventus in 1987, but returned to Anfield the following year. Chris Waddle left Tottenham for Marseille in 1989 and stayed there for three years before returning to England to sign for Sheffield Wednesday. After being appointed Rangers manager in 1986, former Liverpool player Graeme Souness signed a host of English-based players for the Ibrox club.

Even after the ban on English clubs in Europe was lifted, a number of high-profile players moved overseas. Gary Lineker opted to complete his playing career in Japan on leaving Tottenham in 1992, the same year that Paul Gascoigne moved to Italy in a lucrative transfer to Lazio. Another of England's 1990 World Cup stars, David Platt, had been sold by Aston Villa to Italian side Bari in 1991, later playing for Juventus and Sampdoria before returning to England in 1995 to sign for Arsenal - the same year that Gascoigne left Lazio to sign for Rangers in Scotland.

The late 1980s and early 1990s saw the emergence of numerous young players who went on to reach great heights in the game. These include Paul Gascoigne, David Platt, Matt Le Tissier, Lee Sharpe, Ryan Giggs and Paul Merson.

Established great players who were still playing the top in the early 1990s include Ian Rush, Peter Beardsley, Bryan Robson, Steve Bruce, Neville Southall and Ray Wilkins.

This era also saw many famous names hanging up their boots after long and illustrious careers. These include Ray Clemence, Gary Bailey, Alan Hansen, Craig Johnston, Norman Whiteside, Andy Gray and Billy Bonds.

Successful managers of this era include Kenny Dalglish, George Graham, Howard Kendall, Howard Wilkinson, Alex Ferguson, Bobby Gould, John Lyall, Jim Smith, Maurice Evans and Dave Bassett.

1992–2001: The Premier League and Sky Television

The FA Premier League was formed in 1992 when the top twenty-two clubs in English football broke away from the football league, in order to increase their incomes and make themselves more competitive on a European stage, where they would have a budget to compete with most of Europe's top clubs. By selling TV rights separately to the Football League, the clubs increased their income and exposure. The Premier League became the top level of English football, and Division One (later renamed the Football League Championship) fell to the second level.

Manchester United were the first Premiership winners, their first title in 26 years, and under Alex Ferguson, they dominated English football during the 1990s, winning five league titles (including two doubles), one League Cup, one Cup Winners' Cup and, in 1999, a unique treble: the FA Cup, League and Champions League all in one season. Their success was made even more remarkable by the high number of players who came up simultaneously through their youth system, including brothers Gary and Phil Neville, Paul Scholes, Ryan Giggs and David Beckham. This success continued in the new millennium.

United's main challengers for the title in the Premier League's first few years were Blackburn Rovers, led by star striker Alan Shearer, also won their first league title since World War I in 1994–95, and Newcastle United, who famously conceded a 10-point lead at Christmas to lose the title to United in 1995–96. Newcastle had reached the Premiership in 1993 as Division One champions, and in their first Premiership campaign finished third to qualify for the UEFA Cup. They finished second in 1996 and again in 1997, but by the end of the decade had wallowed away to mid table. Liverpool were not initially among the contenders for the Premier League title in the new league's early seasons, as they failed to finish higher than sixth until 1995. Arsenal failed to mount a serious title challenge until 1996-97, when they finished third, before finishing champions and FA Cup winners a year later.

Blackburn failed to sustain their success after the 1995 title triumph, and in 1999 they were relegated to Division One, although they won promotion two years later and won the League Cup a year after that.

A number of other teams challenged for the title in the early Premiership years. Aston Villa finished second in 1993, but declined over the next two seasons (despite a League Cup victory in 1994). They enjoyed a revival in 1996, winning the League Cup and finishing fourth in the Premiership, and by 1999 had qualified for the UEFA Cup five times in seven seasons, though their continental form had been unconvincing. Norwich City were surprise title contenders in 1992–93 under new manager Mike Walker, leading the table at several stages before finishing third - and doing so entered the UEFA Cup for the first time in their history. They achieved a shock win over Bayern Munich before being eliminated by Inter Milan, but were unable to keep up their good progress and in 1995 fell into Division One. By the end of the decade, they had yet to make a Premiership comeback.

Many teams that had succeeded in the 1970s and 1980s did not fare as well in the Premiership. Liverpool were unable to dominate the decade as they had done in the 1970s and 1980s; after their 1990 title win, their only other trophies of the decade were the FA Cup in 1992 and the League Cup in 1995; they finished as low as eighth in 1994 and although they did finish sixth in the first season of the Premier League, they had spent much of that season in the bottom half of the table. Everton fared no better; although they won the FA Cup in 1995, beating Manchester United, they were involved in no less than three relegation battles during the decade and never finished higher than sixth in the league. After a promising start to the decade which included two fifth-place finishes, Manchester City also fought relegation, but lost, slipping into the Division One in 1996 and Division Two in 1998. But two successive promotions saw them back in the Premiership for the 2000–01 season. Nottingham Forest were relegated from the Premier League three times, in 1993 (when Brian Clough retired as manager), 1997 and 1999, and unlike City have yet to return. Both City and Forest endured brief spells in the league's third tier. Forest did enjoy a brief respite in the mid 1990s when they finished third in the Premier League in 1995 and were England's most successful side in Europe the following seasons when they reached the quarter-finals of the UEFA Cup.

Arsenal began the Premier League with moderate league form (a shortage of goals restricting them to 10th place) but excellent form in the cups, as they became the first English team to win both domestic cups in the same season – beating Sheffield Wednesday 2–1 in both finals. They won the Cup Winners' Cup a year later, but manager George Graham was sacked the following February after admitting to receiving a "bung" when signing Danish midfielder John Jensen in 1992. They reached the Cup Winners' Cup final for the second year running under temporary manager Stewart Houston, but finished 12th in the Premiership. They reached fifth the following season under new manager Bruce Rioch, who was sacked for a dispute with the directors soon afterwards and replaced by Frenchman Arsène Wenger. Under Wenger, they won the double in 1998 to become only the second team in English football to repeat this triumph - though, unlike Manchester United two years earlier, with an entirely different set of players.

English football grew wealthier and more popular than ever before, with clubs spending tens of millions of pounds on players and on their wages, which rose to over £100,000 a week for the top stars. This also made it harder for promoted clubs to establish themselves at the top flight. In 1993, newly promoted Middlesbrough lost their top flight status after just one season, while Blackburn finished fourth and Ipswich finished 16th (having occupied fourth place in February). In 1994, newly promoted Swindon went down after winning just five games all season and conceding 100 goals. Newcastle, meanwhile, qualified for the UEFA Cup in third place and West Ham achieved a respectable 13th-place finish. In 1995, newly promoted Nottingham Forest matched Newcastle's success by coming third and qualifying for the UEFA Cup, while Crystal Palace and Leicester City went straight back down. In 1996, newly promoted Bolton Wanderers went straight back down, while Middlesbrough attained a secure 12th place (they would have finished even higher had it not been for a dismal mid-season run of form which saw them endure 10 defeats from 11 games). In 1997, newly promoted Leicester City finished ninth and won the League Cup, while Derby County finished 12th, but Sunderland went straight back down. In 1998, all three newly promoted teams - Bolton Wanderers, Barnsley and Crystal Palace - were relegated straight back to Division One. In 1999, Middlesbrough attained an impressive ninth-place finish, but Charlton Athletic and Nottingham Forest were relegated.

The Premier League was decreased from 22 to 20 clubs in 1995.

Attendances were often restricted during the first two or three seasons of the Premiership, as clubs rebuilt their stadiums to comply with the requirement to be all-seater by the 1994-95 season, and most clubs were left with a lesser capacity than in the era of terracing. Some clubs had fitted seating into their terracing as a cost effective short-term measure, but many clubs were often faced with sell-outs for matches due to a high demand for tickets, and began to further expand their stadiums or investigate the possibility of relocation. In 1995, newly promoted Middlesbrough moved into the new 30,000-seat Riverside Stadium after 92 years at Ayresome Park - this was the first new stadium in the top flight of English football since Manchester City had moved into Maine Road in 1923. Over the next few years, a number of other Premier League and Division One clubs moved into new stadiums.

The national team over this period varied in their success, failing to qualify for the 1994 World Cup but reaching the semi-finals in Euro 96, losing on penalties to Germany at the semi-final stage. They also achieved automatic qualification for the 1998 World Cup, losing to Argentina on penalties in the Second Round. Manager Graham Taylor had quit in November 1993 after failing to attain a World Cup place, and his successor Terry Venables left after the encouraging Euro 96 campaign due to off-the-field disputes. His successor Glenn Hoddle took England to the World Cup, but was fired the following February after a controversial newspaper interview in which he suggested that disabled people were being punished for sins in a previous life. His successor Kevin Keegan achieved the task of attaining qualification for Euro 2000.

The trend for clubs to relocate to new stadiums accelerated throughout the 1990s. By the end of the decade, Walsall, Chester City, Milwall, Huddersfield Town, Northampton Town, Middlesbrough, Derby County, Sunderland, Bolton Wanderers, Stoke City, Reading and Wigan Athletic had all moved to new stadiums, and several other clubs were planning to relocate. This was due to the requirement that all Premier League and Division One stadiums had to have all-seater stadiums by the start of the 1994–95 season, although standing accommodation was still permitted at Division Two and Three stadiums, as well as non-league venues.

Into the 21st century, some clubs who initially redeveloped their old stadiums later decided to relocate, often after their success on the field had driven ticket demand to a level which the new capacities were unable to accommodate. These include Southampton, Leicester City and Arsenal.

Prominent footballers who emerged during the 1990s include Ryan Giggs, David Beckham, Michael Owen, Sol Campbell, Chris Sutton, Robbie Fowler, Gary Neville and Rio Ferdinand.

As well as British and Irish talent, there were numerous foreign imports to the English game during the decade who went on to achieve stardom with English clubs. These include Eric Cantona, Jürgen Klinsmann, Dennis Bergkamp, Gianfranco Zola, Patrick Vieira and Peter Schmeichel. The number of foreign players in the English game rose dramatically during the second half of the 1990s following a relaxation of limits on foreign players, with clubs being allowed to field an unlimited number of players from EU member countries in domestic and European competitions.

Many experienced players whose careers began during the 1980s were still playing at the highest level as the 1990s drew to a close. These include David Seaman, Tony Adams, Gary Pallister, Colin Hendry, Paul Ince, Alan Shearer and Mark Hughes.

The decade also saw the illustrious careers of numerous legendary players draw to a close. These include Bryan Robson, Gordon Strachan, Ian Rush, Peter Beardsley, Steve Bruce, John Barnes and Peter Shilton.

Successful managers of this era include Alex Ferguson, Kenny Dalglish, Arsène Wenger, Ruud Gullit, Gianluca Vialli, George Graham, Joe Royle, Frank Clark, Brian Little and Martin O'Neill.

2003–present: Financial polarisation

In England, as in Europe in general, the early first decade of the 21st century saw the financial bubble burst, with the collapse of ITV Digital in May 2002 leaving a hole in the pockets of the Football League clubs who had relied on their television money to maintain high wages. Although no Football League teams collapsed (no team has done so since Maidstone United in 1992), many entered administration, including Leicester City and Bradford City. From the 2004–05, administration for any Premier League or Football League club would mean a 10-point deduction. Most of the non-league divisions adopted a similar penalty.

Another club that faced financial ruin was Leeds United; having reached the Champions League semi-finals in 2000–01 they looked set for dominance on the domestic and European scene, but after failing to qualify for the competition the following season, they were unable to cover the loans they had taken out to fund their spending. They were forced to sell their ground (and lease it back) and many of their best players. They were relegated at the end of the 2003–04 season and three years later slipped into the league's third tier for the first time in their history, although their debts have since been substantially reduced. However, they have still yet to return to the Premier League more than a decade after being relegated.

At the same time, the country's richest clubs continued to grow, with the wages of top players increasing further.