Offside (association football)

.jpg)

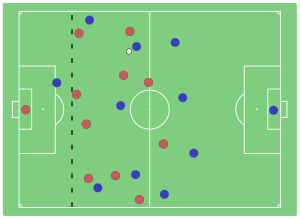

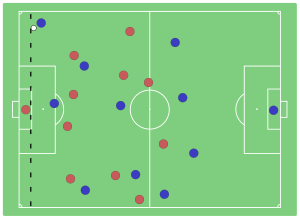

Offside is one of the laws of association football, codified in Law 11 of the Laws of the Game. The law states that a player is in an offside position if any of their body parts, except the hands and arms, are in the opponents' half of the pitch, and closer to the opponents' goal line than both the ball and the second-last opponent (the last opponent is usually, but not necessarily, the goalkeeper).[1]

Being in an offside position is not an offence in itself, but a player so positioned when the ball is played by a teammate can be judged guilty of an offside offence if they become "involved in active play", "interfere with an opponent", or "gain an advantage" by being in that position.

Significance

Being in an offside position is not an offence in itself; a player who was in an offside position at the moment the ball last touched, or was played, by a teammate, must then become involved in active play in the opinion of the referee, in order for an offence to occur. When the offside offence occurs, the referee stops play and awards an indirect free kick to the defending team from the place where the offending player became involved in active play.[1]

The offside offence is neither a foul nor misconduct as it does not belong to Law 12. Like fouls, however, any play (such as the scoring of a goal) that occurs after an offence has taken place, but before the referee is able to stop the play, is nullified.[2] The only time an offence related to offside is cautionable is if a defender deliberately leaves the field in order to deceive their opponents regarding a player's offside position, or if a forward, having left the field, returns and gains an advantage. In neither of these cases is the player being penalised for being offside, they are being cautioned for acts of unsporting behaviour.[1]

An attacker who is able to receive the ball behind the opposition defenders is often in a good position to score. The offside rule limits attackers' ability to do this, requiring that they be onside when the ball is played forward. Though restricted, well-timed passes and fast running allow an attacker to move into such a situation after the ball is kicked forward without committing the offence. Officiating decisions regarding offside, which can often be a matter of only centimeters or inches, can be critical in games, as they may determine whether a promising attack can continue, or even if a goal is allowed to stand.

One of the main duties of the Assistant Referees is to assist the referee in adjudicating offside[3] — their position on the sidelines giving a more useful view sideways across the pitch. Assistant referees communicate that an offside offence has occurred by raising a signal flag.[4] :191 However, as with all officiating decisions in the game, adjudicating offside is ultimately up to the referee, who can overrule the advice of their assistants if they see fit.[5]

Application

The application of the offside rule may be considered in three steps: offside position, offside offence, and offside sanction.

Offside position

A player is in an 'offside position' if they are in the opposing team's half of the field and also "nearer to the opponents' goal line than both the ball and the second-last opponent."[1] The 2005 edition of the Laws of the Game included a new IFAB decision that stated, "In the definition of offside position, 'nearer to his opponents' goal line' means that any part of their head, body or feet is nearer to their opponents' goal line than both the ball and the second last opponent. The arms are not included in this definition".[6] By 2017, the wording had changed to say that, in judging offside position, "The hands and arms of all players, including the goalkeepers, are not considered." [1] In other words, a player is in an offside position if two conditions are met:

- Any part of the player's head, body or feet is in the opponents' half of the field (excluding the half-way line).

- Any part of the player's head, body or feet is closer to the opponents' goal line than both the ball and the second-last opponent.[1]

The goalkeeper counts as an opponent in the second condition, but it is not necessary that the last opponent be the goalkeeper.

Offside offence

A player in an offside position at the moment the ball is touched or played by a teammate is only penalised for committing an offside offence if, in the opinion of the referee, they become involved in active play by:

- Interfering with play

- "playing or touching the ball passed or touched by a team-mate"[1]

- Interfering with an opponent

- "preventing an opponent from playing or being able to play the ball by clearly obstructing the opponent’s line of vision or

- challenging an opponent for the ball or

- clearly attempting to play a ball which is close to them when this action impacts on an opponent or

- making an obvious action which clearly impacts on the ability of an opponent to play the ball"[1]

- Gaining an advantage by playing the ball or interfering with an opponent when it has

- "- rebounded or been deflected off the goalpost, crossbar, match official or an opponent

- - been deliberately saved by any opponent" [1]

In addition to the above criteria, in the 2017–18 edition of the Laws of the Game, the IFAB made a further clarification that, "In situations where a player moving from, or standing in, an offside position is in the way of an opponent and interferes with the movement of the opponent towards the ball this is an offside offence if it impacts on the ability of the opponent to play or challenge for the ball."[1]

There is no offside offence if a player receives the ball directly from a goal kick, a corner kick, a throw-in, or a dropped-ball. It is also not an offence if the ball was last deliberately played by an opponent (except for a deliberate save). In this context, according to the IFAB, "A ‘save’ is when a player stops, or attempts to stop, a ball which is going into or very close to the goal with any part of the body except the hands/arms (unless the goalkeeper within the penalty area)." [1]

An offside offence may occur if a player receives the ball directly from either a direct free kick or an indirect free kick.

Since offside is judged at the time the ball is touched or played by a teammate, not when the player receives the ball, it is possible for a player to receive the ball significantly past the second-to-last opponent, or even the last opponent, without committing an offence.

Determining whether a player is "involved in active play" can be complex. The quote, "If he's not interfering with play, what's he doing on the pitch?" has been attributed to Bill Nicholson[7] and Danny Blanchflower.[8] In an effort to avoid such criticisms, which were based on the fact that phrases such as "interfering with play", "interfering with an opponent", and "gaining an advantage" were not clearly defined, FIFA issued new guidelines for interpreting the offside law in 2003; and these were incorporated into Law 11 in July 2005.[6] The new wording sought to define the three cases more precisely, but a number of football associations and confederations continued to request more information about what movements a player in an offside position could make without interfering with an opponent. In response to these requests IFAB circular 3 was issued in 2015 to provide additional guidance on the criteria for interfering with an opponent. This additional guidance is now included in the main body of the law and forms the last 3 conditions under the heading "Interfering with an opponent" as shown above. The circular also contained additional guidance on the meaning of a save, in the context of a ball that has "been deliberately saved by any opponent." [9]

Officiating

In enforcing this rule, the referee depends greatly on an assistant referee, who generally keeps in line with the second-to-last opponent, the ball, or the halfway line, whichever is closer to the goal line of their relevant end.[4]:176 An assistant referee signals for an offside offence by first raising their flag to a vertical position and then, if the referee stops play, by partly lowering their flag to an angle that signifies the location of the offence:[4]:192

- Flag pointed at a 45-degree angle downwards: offence has occurred in the third of the pitch nearest to the assistant referee;[3]:73

- Flag parallel to the ground: offence has occurred in the middle third of the pitch;[3]:73

- Flag pointed at a 45-degree angle upwards: offence has occurred in the third of the pitch furthest from the assistant referee.[3]:73

The assistant referees' task with regard to offside can be difficult, as they need to keep up with attacks and counter-attacks, consider which players are in an offside position when the ball is played, and then determine whether and when the offside-positioned players become involved in active play. The risk of false judgement is further increased by the foreshortening effect, which occurs when the distance between the attacking player and the assistant referee is significantly different from the distance to the defending player, and the assistant referee is not directly in line with the defender. The difficulty of offside officiating is often underestimated by spectators. Trying to judge if a player is level with an opponent at the moment the ball is kicked is not easy: if an attacker and a defender are running in opposite directions, they can be two metres apart in less than a second.

Some researchers believe that offside officiating errors are "optically inevitable".[10] It has been argued that human beings and technological media are incapable of accurately detecting an offside position quickly enough to make a timely decision.[11] Sometimes it simply is not possible to keep all the relevant players in the visual field at once.[12] There have been some proposals for automated enforcement of the offside rule.[13]

History

Offside rules date back to codes of football developed at English public schools in the early nineteenth century. These offside rules, which varied widely between schools, were often much stricter than the modern game. In some of them, a player was "off his side" if they were standing in front of the ball.[14] This was similar to the current offside law in rugby, under which any player between the ball and the opponent's goal who takes part in play, is liable to be penalised.[15][16] By contrast, the original Sheffield Rules had no offside rule, and players known as "kick-throughs" were positioned permanently near the opponents' goal.[14]

Offside was probably part of the "Cambridge Rules" from their inception in 1848. A ruleset dating from 1856 found in the library of Shrewsbury School is probably closely modelled on the Cambridge Rules and is thought to be the oldest set still in existence. Rule No. 9 required more than three defensive players to be ahead of an attacker who plays the ball. The rule states:[14]

If the ball has passed a player and has come from the direction of his own goal, he may not touch it till the other side have kicked it, unless there are more than three of the other side before him. No player is allowed to loiter between the ball and the adversaries' goal.

When the original Laws of the Game were first drafted in 1863 no forward passes of any sort were permitted, except for kicks from behind the goal line.[14] The rule states:

6. When a player has kicked the ball any one of the same side who is nearer to the opponent's goal line is out of play and may not touch the ball himself, nor in any way whatever prevent any other player from doing so until the ball has been played, but no player is out of play when the ball is kicked from behind the goal line

As football developed in the 1860s and 1870s, the offside law proved the biggest argument between the clubs. Sheffield got rid of the "kick-throughs" by amending their laws so that one member of the defending side was required between a forward player and the opponents' goal.

The compromise rule that was written into the Laws of the Game in 1866, and eventually adopted universally, was to adopt a form of the Cambridge rule, but with "at least three" rather than "more than three" opponents.[14][17]

In 1924, the concept of passive offside was introduced.[14]

The rule changed to "two opponents" in 1925 and led to an immediate increase in goal-scoring. 4,700 goals were scored in 1,848 Football League games in 1924–25. This number rose to 6,373 goals (from the same number of games) in 1925–26.[14]

In 1990 the law was amended to adjudge an attacker as onside if level with the second-to-last opponent. This change was part of a general movement by the game's authorities to make the rules more conducive to attacking football and help the game to flow more freely.[14]

Unadopted experiments

During the 1973–74 and 1974–75 seasons, an experimental version of the offside rule was operated in the Scottish League Cup and Drybrough Cup competitions.[18] The concept was that offside should only apply in the last 18 yards of play (inside or beside the penalty area).[18] To signify this, the horizontal line of the penalty area was extended to the touchlines.[18] FIFA President Sir Stanley Rous attended the 1973 Scottish League Cup Final, which was played using these rules.[18] The manager of one of the teams involved, Celtic manager Jock Stein, complained that it was unfair to expect teams to play under one set of rules in one game and then a different set a few days before or later.[18] The experiment was quietly dropped after the 1974–75 season, as no proposal for a further experiment or rule change was submitted for the Scottish Football Association board to consider.[18]

In the 1987–88 season, the Football Association was authorised by the International Football Association Board to test an experimental rule change, whereby no attacker could be offside directly from a free-kick.[19] :32 The competition chosen for this experiment was the Football Conference. The change was not deemed a success, as the attacking team could pack the penalty area for any free-kick (or even have several players stand in front of the opposition goalkeeper) and the rule change was not introduced at a higher level.

Offside trap

Pioneered in the early 20th century by Arsenal[20] and later adopted by influential Argentine coach Osvaldo Zubeldía,[21] the offside trap is a defensive tactic designed to force the attacking team into an offside position. Just before an attacking player is played a through ball, the last defender(s) move up field, isolating the attacker into an offside position. The execution requires careful timing by the defence and is considered a risk, since running up field against the direction of attack may leave the goal exposed. Now that changes to the interpretations of "interfering with play, interfering with an opponent and gaining an advantage" mean a player is not guilty of an offside offence unless they become directly and clearly involved in active play, players not involved in active play cannot be "caught offside", making the tactic riskier. An attacker, upon realizing he is in an offside position, may simply choose to avoid interfering with play until the ball is played by someone else first.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Law 11 - Offside". Laws of the Game 2017-18. Zurich: International Football Association Board. 2017-05-22. pp. 91–95. Retrieved 2017-09-28.

- ↑ "Law 10 - Determining the Outcome of a Match". Laws of the Game 2017-18. Zurich: International Football Association Board. 2017-05-22. pp. 87–90. Retrieved 2017-09-28.

- 1 2 3 4 "Law 6 - The Other Match Officials". Laws of the Game 2017-18. Zurich: International Football Association Board. 2017-05-22. pp. 69–74. Retrieved 2017-09-28.

- 1 2 3 "Practical Guidelines for Match Officials". Laws of the Game 2017-18. Zurich: International Football Association Board. 2017-05-22. pp. 173–202. Retrieved 2017-09-28.

- ↑ "Law 5 - The Referee". Laws of the Game 2017-18. Zurich: International Football Association Board. 2017-05-22. pp. 61–67. Retrieved 2017-09-28.

- 1 2 "Amendments to the Laws of the Game 2005" (PDF). Fédération Internationale de Football Association. 17 May 2005. p. 3. Retrieved 2017-09-28.

- ↑ "Guardian Football: The Knowledge". The Guardian. 2006-09-13. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ Barry Davies (1994-05-09). Commentary: Brazil vs Netherlands, World Cup 1994 (YouTube). United States: FIFA / BBC. Retrieved 2014-05-26.

- ↑ "IFAB Circular 3". Zurich: The International Football Association Board. 15 July 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- ↑ Oudejans, Raôul R. D.; Verheijen, Raymond; Bakker, Frank C.; Gerrits, Jeroen C.; Steinbrückner, Marten; Beek, Peter J. (2000), "Errors in judging 'offside' in football", Nature, 404 (6773): 33–33, doi:10.1038/35003639

- ↑ FB Maruenda (2009), An offside position in football cannot be detected in zero milliseconds, doi:10.1038/npre.2009.3835.1, hdl:10101/npre.2009.3835.1

- ↑ B Maruenda (2004), "Can the human eye detect an offside position during a football match?", BMJ, British Medical Journal, 329 (7480): 1470–2, doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7480.1470, PMC 535985, PMID 15604187 Correction: "Can the human eye detect an offside position during a football match?", BMJ, 330 (7484): 188, 2005, doi:10.1136/bmj.330.7484.188

- ↑ S Iwase, H Saito (2002), Tracking soccer player using multiple views, Proceedings of the IAPR Workshop on Machine Vision, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.143.9703

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Carosi, Julian (2006). "The History of Offside" (PDF). Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ↑ "Law 11 - Offside and Onside in General Play". World Rugby. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ↑ "Law 14 - Offside". Rugby Football League. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ↑ "150 years of Association Football ~ How the Rules have changed". Archived from the original on 12 June 2013. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Russell, Grant (1 April 2011). "How the Scottish FA tried to revolutionise the offside law". www.sport.stv.tv. STV. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ↑ "IFAB 1987 Approved Meeting Minutes" (PDF). International Football Association Board. 7 June 1989. p. 32. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ↑ Wilson, Jonathan (13 April 2010), The Question: Why is the modern offside law a work of genius?

- ↑ Intercontinental Cup 1968, archived from the original on 6 November 2012

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Offside (association football). |

- Laws of the Game 2017-18 — Law 11 - Offside is on pages 93–95. Pages 195 - 201 give visual diagrams of situations in which offside offences occur or do not occur under Law 11.

- FIFA Offside Presentation, June 2005

- Offside explained at AskTheRef.com

- FIFA interactive guide

- Professional Referee Organization offside discussion, from 2015 pre-season (includes video examples)