Historical markers of the Philippines

Historical markers (Filipino: panandang pangkasaysayan) are installed by the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP) in the Philippines and places abroad that signify important events, persons,[1][2] structures,[3] and institutions in Philippine national and local histories.[4] The plaques themselves are permanent signs installed by the NHCP in publicly visible locations on buildings, monuments, or in special locations. Local municipalities and cities can also install markers of figures and events of local significance. Though they may have the permission of the NHCP, these markers are barred from using the seal of the Republic of the Philippines.[5]

While many Cultural Properties have historical markers installed, not all places marked with historical markers are designated into one of the particular categories of Cultural Properties. As of January 2012, the total number of historical markers is 459;[6] however, the number of markers from all these lists is more than 1,300.

History

Before 1933, several civic efforts have been initiated to create monuments and to mark historic sites and events, such as Cry of Balintawak, José Rizal Monument, and the birthplace of Andrés Bonifacio. However, many more historical sites have not been recognized or marked.[7]

The earliest predecessor of the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP) was the Philippine Historical Research and Markers Committee (PHRMC). Established in October 23, 1933[7] via Executive Order 451 during the governorship of Frank Murphy during the American colonial era, one of its tasks was to mark cultural and historical antiquities in Manila, which was later expanded to cover the rest of the Philippines. The first markers were installed in 1934, including ones for Church of San Agustin, Fort Santiago, Plaza McKinley, Roman Catholic Cathedral of Manila, San Sebastian Church, Concordia College, Manila Railroad Company, Dr. Lorenzo Negrao, and University of Santo Tomas (Intramuros site). Issuance of markers stopped during the Second World War. Some of these markers were either lost or destroyed during the war and new markers were installed as replacements for San Agustin Church and Manila Cathedral. Throughout the years, some markers have also been reportedly missing as they were stolen and sold as scrap metal.[8] The installation of markers was continued by the successors of the PHRMC: the Philippines Historical Committee (PHC), National Historical Institute (NHI), and the National Historical Commission (NHCP). The standard style of markers has changed throughout the years.

The language of the markers are mostly and primarily in Filipino, with markers also in English and Spanish. The first marker to contain a regional language was installed to commemorate the Cebu Provincial Capitol in Cebu City. The markers, both in Cebuano and Filipino, were installed in 2008. The first marker in Ilocano was installed to commemorate Mansion House in Baguio City in 2009. The first marker in Kapampangan was installed to commemorate the Holy Rosary Parish Church in Angeles City in 2017. Historical markers outside of the Philippines may also be written in the local language of the country where the marker is installed such as German in Berlin, Germany[9] and French in Ghent, Belgium[10] (both markers commemorate José Rizal). Two of the first markers outside of the Philippines were installed in Ghent, Belgium, commemorating the residence of José Rizal when the El Filibusterismo was published, and in Dezhou, China, commemorating Paduka Batara, a King of Sulu who paid tribute to the Yongle Emperor and died there. Both were installed in 1959.

Markers related to Rizal occur the most, and Filipino historian Teodoro A. Agoncillo revealed that during his time (he served the NHCP from 1963 to 1985), their efforts in the board were mostly spent on approving, disucssing, and rewriting the marker texts. With the number of marker requests relating to Rizal, he joked “Aba! Pati ba naman eskinitang inihian ni Rizal ibig lagyan ng marker!” (What, they even want us to mark obscure side streets where Rizal relieved himself!).[8]

In 2002, during the unveiling ceremony of the marker National Federation of Women’s Clubs in the Philippines in Manila Hotel, former president Fidel Ramos joked that the curtain raising reminded him of striptease, and everybody laughed. That was the last time that the curtains were pulled upward, and from then, the unveiling involves curtain pulling instead.[11]

In 2011, the NHCP stated that it will pursue more markers for Visayas and Mindanao for their further inclusion in national history, citing the concentration of markers in Luzon.[12]

The Kudan, the Philippine embassy building in Tokyo, has been declared a national historical landmark by the NHCP and was granted a historical marker on March 3, 2014. It is the first and currently the only overseas site to be granted such status.[13] During the unveiling of the marker, Ambassador Manuel Lopez called the building as the crown jewel of Philippine foreign service.[14]

On June 3, 2016, the NHCP, for the first time, installed a marker for a nameless personality. A marker was installed in Macabebe, commemorating the leader of the Battle of Bangkusay Channel, the "first native to give up his life for independence."[15]

Criteria and policies

The following are the policies issued by the NHCP on the installation of markers:[16]

- Markers shall be installed for Filipino heroes, historic events and places involving historical acts and patriotic endeavors to dramatize the need to focus to the national consciousness the history of our country from the Filipino viewpoint and to evoke pride in our national heritage and identity.

- Installation of historical markers that honor Filipino heroes shall be undertaken after proper and thorough study.

- Historical markers shall only be installed in places with great historical value as determined by the NHI Board.

- Historical markers for religious personalities maybe installed in recognition of social or historical value.

- Historical marker shall not be installed to honor persons deceased less than fifty years, unless they are considered outstanding figures.

- Request for historical markers may be granted during the centenary year of deserving persons, places or structures.

- Historical markers shall not be installed in honor of persons who are still living.

- Historical markers may be installed in honor of foreigners, only in exceptional cases.

- Markers of local significance shall be allowed upon approved application to the NHI provided they are installed and financed by the agency, person or organization making the request and in such cases, the seal of the Republic of the Philippines shall not be allowed to be used.

- In consonance with the national policy, all texts of historical markers shall be in the National Language.

- The historical marker shall have a uniform design, size and materials. The NHI shall exercise the exclusive right (patent) over its use and production.

- The historical markers are government property. Any act to destroy or remove the said markers without the written authority from the NHI Board shall be charged criminally in accordance with existing laws.The NHI shall conceptualize the standard design, size and materials of the pedestals for the historical marker.

- To ensure the protection, upkeep and maintenance of the historical markers, the NHI and the client (i.e. local executives, descendant of the hero, etc.) shall both officially agree and sign the Certificate of Transfer.

Historical marker attached to the façade of a structure

Historical marker attached to the façade of a structure Historical marker on a monument

Historical marker on a monument- Historical marker on a stand-alone pedestal

Historical marker inside a building

Historical marker inside a building

Issues

Some historical markers have also caused issues and controversies due to different reasons.

- Baguio City Hall – Markers have also been used to justify the historicity of the place and help preserve the area, like in the issue of developing the City Hall site in Baguio. Despite the lack of resolutions or consultations, former NHCP Chairperson Maria Serena Diokno affirmed the historical significance of the area against alterations on the historical site under the National Cultural Heritage Act.[17]

- Blood Contact Between Sikatuna and Legaspi – The site of the historical marker of the Sandugo, or the blood compact between Sikatuna and Legazpi became an issue because of the NHCP board resolution that the event site was located off the waters of Loay and not Tagbilaran. Despite the resolution, the marker remains in its original place.[18]

- The Code of Kalantiaw – This historical marker in Batan, installed on December 8, 1956,[19] remained in place after William Henry Scott in 1968 proved that The Code of Kalantiaw and Datu Kalantiaw to be hoaxes and even after a resolution was issued by the NHI in 2004.

- Ferdinand Marcos 1917-1989 – A historical marker commemorating the centennial birth anniversary of President Ferdinand Marcos in Batac, Ilocos Norte unveiled on September 11, 2017 became controversial and became a case for historical revisionism, following the controversial burial of the late dictator.[20] Baybayin, an Ateneo de Manila student organization, issued an alternative marker online containing atrocities under the Marcos regime, as well as his burial as a statement against historical revisionism.[21]

- The First Congress of the Republic of the Philippines 1946 ~ 1949 – The marker concerning the first congress is the biggest marker made, measuring at 52x72 inches. The 1946 marker was replaced on January 27, 2010 when governor Carlos Padilla of Nueva Vizcaya asked why his father, Constancio Padilla was missing from the list of the legislators. Luis Taruc, Jesus Lava, and Amado Yuson of the Democratic Alliance were not in the marker even though they appeared in the Congressional Records, while Luis Clarin, Carlos Fortich, and Narciso Ramos were in the 1946 marker but not in the present Congressional Records. The Lava brothers and Yuzon were dismissed from Congress, although the latter moved to the Nacionalista Party. Fortich died before completing his term and was replaced by his widow, Remedios Ozamis Fortich. Ramos won as the congressman for the 5th district of Pangasinan, but was appointed soon after to the United Nations, and was replaced by Cipriano Allas.[11]

- Francisco "Soc" Rodrigo 1914-1998 – There is the case of a possible relocation of a historical marker dedicated to Francisco "Soc" Rodrigo in Bulakan over ownership issues of the heritage house.[22]

- Labanan sa Karagatan ng Sibuyan Battle of Sibuyan Sea – Related to the discovered shipwrecks (Japanese ship Musashi) in Sibuyan Island, Romblon, a group has been pushing the transfer of the marker to the said island from the town of Alcantara.[23]

- La Ignaciana – The historical marker (installed in 1939) of the Jesuit institution La Ignaciana in Santa Ana, Manila was stolen. A replacement marker was planned to be installed by the end of 2014,[24] but it never took place.

- Macapagal-Macaraeg Ancestral House – The marker for the mid-century Macapagal-Macaraeg house in Iligan, issued in 2002, became an issue because President Diosdado Macapagal never lived in the said house, although it became a home for his daughter President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo.[25]

- Memorare – Days before the Bonifacio Day of 2017, reports surface the demolition of the Bonifacio centennial monument in Makati City, along with its historical marker. It was done by the Department of Public Works and Highways to build a bridge connecting Ortigas and Bonifacio Global City business districts without informing and seeking the approval of the NHCP. DPWH, however, stated that it informed the local government unit and temporarily removed the statue to protect it from the construction. The department also said that it has allotted ₱39 million for the restoration of the park after the project has been completed in 2020.[26][27][28]

- Memorare – A statue and marker, named Filipina Comfort Women Statue, remembering the comfort women of World War II, installed on December 8, 2017 along Baywalk, Roxas Boulevard, Malate, Manila, caught the attention from the officials from the Department of Foreign Affairs and the Japanese Embassy in Manila.[29] In response, Teresita Ang-See, said that the memorial should not become an insult versus Japan.[30] On April 27, 2018, the DPWH removed the memorial for a drainage improvement project along the Baywalk. Many individuals and groups, including Gabriela Women's Party condemned the removal, stating historical revisionism and submission to Japanese policy. They also stated that this has been an unlawful removal, since the heritage act protects markers and memorials by the NHCP. [31][32] President Duterte remarked that the memorial can be placed in a private property, since the state would not want to "antagonize" other countries.[33]

- Mindanao Garden of Peace, Corregidor Island – On March 18, 2015, a marker pertaining to the Jabidah massacre was installed in Corregidor, Cavite City.[34] It must be noted that despite referring to the said event, the marker was entitled "Mindanao Garden of Peace, Corregidor Island" and the marker text did not contain the name "Jabidah."

- Patricio Mariano (1877-1935) – The historical marker dedicated to Patricio Mariano in Escolta, Binondo, Manila received social media attention regarding its then derelict state. On January 28, 2015, on the occasion of Mariano's 80th death anniversary, the Escolta Revival Movement wrote to the NHCP regarding the situation of the marker. The NHCP renovated the marker the day after.[35]

- Pisamban Maragul (Pisamban ning Angeles) and Mansyong Pamintuan The Large Church (Church of Angeles) and Pamintuan Mansion –The case of Angeles City markers of Santo Rosario Church and the Pamintuan Mansion became example of markers replaced by new ones bearing rectified information. The latter markers indicate that the anniversary of the Philippine independence was celebrated there in 1899; however, the former venue was discovered to have been the real place of the commemoration.[36]

- Pook Kung Saan Sinulat ang "Filipinas", Liriko ng Pambansang Awit Bautista, Pangasinan Site Where "Filipinas", Lyrics to the National Anthem, was Written Bautista, Pangasinan – Delayed negotiations with the family that owns Casa Hacienda prompted the local government of Bautista to install the marker where Filipinas/Lupang Hinirang was composed to the town's plaza instead.[37]

- Pook Na Kinamatayan ni Doña Aurora Aragon Quezon Deathplace of Aurora Aragon Quezon – A marker was rededicated on the site on April 28, 2013 after the original marker dated February 13, 1991 went missing. The marker in Bongabon stands on the site where Aurora Aragon Quezon was assassinated.[38]

- Unang Putok sa Digmaang Filipino-Amerikano and Tulay ng San Juan First Shot in the Filipino-American War and San Juan Bridge – Following the move to relocate the marker of the first shot of the Filipino-American War from San Juan Bridge to the corner of Sociego and Silencio, Santa Mesa, Manila, former NHI Chairperson Ambeth Ocampo was declared persona non grata in San Juan. The NHI then issued a replacement marker on the bridge, indicating it as a boundary between Filipino and American soldiers during the war, instead of it being the site of the first shot.[39]

- In 2004, the NHCP approved a marker for the Alberto House, Biñan for its historicity in relation to Teodora Alonso, José Rizal, and the city. However, the marker did not push through because the owner refused to follow preservation requests.[40]

- Some markers have been worn out or have faded texts because of natural reasons. There have also been some markers that have been refused to be read by other Filipinos because the language was not in a local one.[8]

Historical markers by region

These lists of historical markers installed by the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP) are annotated lists of people, places, or events in the Philippines that have been commemorated by cast-iron plaques issued by the said commission.

There are markers installed by the NHCP outside the Philippines commemorating Philippine-related events, and there are separate lists on these markers, by region.

- National Capital Region

- Cordillera Administrative Region

- Region I: Ilocos Region

- Region II: Cagayan Valley

- Region III: Central Luzon

- Region IV-A: Calabarzon

- Region IV-B: Mimaropa

- Region V: Bicol Region

- Region VI: Western Visayas

- Region VII: Central Visayas

- Region VIII: Eastern Visayas

- Region IX: Zamboanga Peninsula

- Region X: Northern Mindanao

- Region XI: Davao Region

- Region XII: Soccsksargen

- Region XIII: Caraga

- Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao

- Overseas

Gallery

- Ateneo de Manila, Intramuros, Manila (currently within NHCP storage)

Nielson Tower, Ayala, Makati City

Nielson Tower, Ayala, Makati City Pang-alaalang Bantayog (World War II heroes of Pasig memorial), Caruncho Avenue, Malinao, Pasig City

Pang-alaalang Bantayog (World War II heroes of Pasig memorial), Caruncho Avenue, Malinao, Pasig City.jpg) Leon Ma. Guerrero (1915 - 1982), Nuestra Señora de Guia Plaza, Ermita, Manila

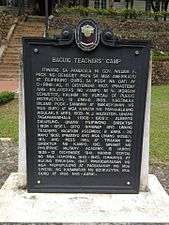

Leon Ma. Guerrero (1915 - 1982), Nuestra Señora de Guia Plaza, Ermita, Manila Baguio Teachers' Camp, Baguio City

Baguio Teachers' Camp, Baguio City- Mansion Syquia, Vigan City, Ilocos Sur

Church of Tumauini, Tumauini, Isabela

Church of Tumauini, Tumauini, Isabela Republika Pilipina 1898-1901, Church of the Immaculate Conception, Malolos City, Bulacan

Republika Pilipina 1898-1901, Church of the Immaculate Conception, Malolos City, Bulacan- Ang Parokya ng Santa Cruz (The Parish of Santa Cruz), Tanza, Cavite

Church of Ibaan, Ibaan, Batangas

Church of Ibaan, Ibaan, Batangas Labinlimang Martir ng Bicol (Fifteen Martyrs of Bicol), Naga City, Camarines Sur

Labinlimang Martir ng Bicol (Fifteen Martyrs of Bicol), Naga City, Camarines Sur Miag-ao Church, Miag-ao, Iloilo

Miag-ao Church, Miag-ao, Iloilo- Carlos P. Garcia House, Tagbilaran City, Bohol

Bantayan ng Biliran (Biliran Watchtower), Biliran, Biliran

Bantayan ng Biliran (Biliran Watchtower), Biliran, Biliran Fort Pilar, Zamboanga City

Fort Pilar, Zamboanga City Fuerte de la Concepcion y del Triunfo, Ozamis, Misamis Occiental

Fuerte de la Concepcion y del Triunfo, Ozamis, Misamis Occiental Davao City Hall, Davao City, Davao del Sur

Davao City Hall, Davao City, Davao del Sur- Simbahang Inmaculada Concepcion ng Tamontaka (Immaculate Concepcion Church of Tamontaka), Cotabato City

José Rizal, Brussels, Belgium

José Rizal, Brussels, Belgium José Rizal, Wilhemsfeld, Germany

José Rizal, Wilhemsfeld, Germany

See also

References

- ↑ "Cardinal's historical marker unveiled". GMA News. 7 September 2008. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ↑ Orejas, Tonette (13 June 2016). "NHCP corrects error over true hero of Battle of Bangkusay". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ↑ Reyes, Jonas (27 November 2013). "Historical marker in Subic unveiled". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ↑ Rosales, Mellanie (3 December 2010). "UP Cebu unveils historical marker". The Freeman. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ↑ "GUIDELINES_IDENTIF CLASSIF AND RECOG OF HIST SITES & STRUCTS IN THE PHIL.pdf". Google Docs. Retrieved 2018-02-02.

- ↑ "LIST OF HISTORIC SITES AND STRUCTURES INSTALLED WITH HISTORICAL MARKERS" (PDF). National Historical Commission of the Philippines. 16 January 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 July 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- 1 2 Historical Markers Placed by the Philippine Historical Committee. Manila: Bureau of Printing. 1958.

- 1 2 3 Ocampo, Ambeth R. "Circumnavigator's paradox". Retrieved 2017-12-21.

- ↑ https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q23854678. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q30127147. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 "PressReader.com - Connecting People Through News". www.pressreader.com. Retrieved 2018-01-29.

- ↑ "2011-2012.pdf". Google Docs. Retrieved 2018-01-22.

- ↑ "Envoy's residence in Japan becomes PHL's 1st overseas historical landmark". GMA News Online. Retrieved 2018-01-29.

- ↑ "Philippine Ambassador's Official Residence in Tokyo Proclaimed Philippine "National Historical Landmark" | Philippine Embassy – Tokyo, Japan". tokyo.philembassy.net. Retrieved 2018-01-29.

- ↑ "PressReader.com - Connecting People Through News". www.pressreader.com. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- ↑ "POLICIES ON THE INSTALLATION OF HISTORICAL MARKERS". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 2017-12-21.

- ↑ "NCCA cautions Baguio on developing historical sites – Northern Dispatch Weekly". www.nordis.net. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- ↑ "Retouch the law before 'touching' Sandugo marker: Chatto to NHCP". Province of Bohol. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- ↑ "The Myth of the Code of Datu Kalantiaw" (PDF). Official Gazette. Government of the Philippines. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- ↑ Cigaral, Ian Nicolas. "Historical revisionism legitimized? NHCP issues marker for Marcos monument". philstar.com. Retrieved 2017-12-19.

- ↑ "Ateneo group puts forward own version of Marcos marker". philstar.com. Retrieved 2017-12-19.

- ↑ "Ownership issues may cause relocation of Soc Rodrigo's historical marker". The Real A.C.T. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- ↑ Cinco, Maricar. "Discovery of Japanese wreck 'surprises' Sibuyan folk". Retrieved 2018-01-13.

- ↑ Sembrano, Edgar Allan M. "NCCA issues cease order vs Sta. Ana, Manila development". Retrieved 2017-12-21.

- ↑ "The Fake National Heritage House of Gloria Arroyo". heritage.elizaga.net. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- ↑ Sembrano, Edgar Allan M. "DPWH topples Bonifacio centennial monument in Makati". Retrieved 2018-01-28.

- ↑ Adel, Rosette. "DPWH: Makati gov't informed of removal of Bonifacio monument". philstar.com. Retrieved 2018-01-28.

- ↑ "What happened to the centennial Bonifacio monument in Taguig?". Rappler. Retrieved 2018-01-28.

- ↑ News, ABS-CBN. "Manila 'comfort woman' statue catches DFA's attention". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- ↑ See, Aie Balagtas. "'Comfort woman' statue not an insult vs Japan'". Retrieved 2018-01-11.

- ↑ "LOOK: Comfort Woman statue on Roxas Boulevard removed". GMA News Online. Retrieved 2018-04-30.

- ↑ "Gabriela condemns govt's removal of comfort woman statue". Kodao Productions. 2018-04-28. Retrieved 2018-04-30.

- ↑ "Duterte: Removed comfort woman statue can be put somewhere else". GMA News Online. Retrieved 2018-04-30.

- ↑ Melican, Nathaniel R. "Jabidah massacre shrine marker unveiled". Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- ↑ "Patricio Mariano – Aurora Metropolis". aurorametropolis.wordpress.com (in Tagalog). Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ↑ Orejas, Tonette. "Freedom Day celebrated in church, not mansion". Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- ↑ "Bautista town set to unveil marker as home of "Lupang Hinirang" – Sunday Punch". punch.dagupan.com. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- ↑ https://www.gov.ph/2013/04/27/national-historical-commission-to-unveil-hist-marker-dedicated-to-aurora-quezon/. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Yahoo! Groups". groups.yahoo.com. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- ↑ "Ambeth Ocampo | FILIPINO eSCRIBBLES". filipinoscribbles.wordpress.com. Retrieved 2017-12-21.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Historical markers in the Philippines. |

- A list of sites and structures with historical markers, as of 16 January 2012

- A list of institutions with historical markers, as of 16 January 2012

- National Registry of Historic Sites and Structures in the Philippines

- Policies on the Installation of Historical Markers

- Wikimedia Philippines Historical Markers Map