Hibbertopterus

| Hibbertopterus | |

|---|---|

| |

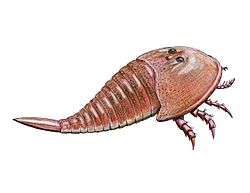

| Restoration of H. scouleri | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Chelicerata |

| Order: | †Eurypterida |

| Superfamily: | †Mycteropoidea |

| Family: | †Hibbertopteridae |

| Genus: | †Hibbertopterus Kjellesvig-Waering, 1959 |

| Type species | |

| †Hibbertopterus scouleri Hibbert, 1836 | |

| Species | |

| |

Hibbertopterus is a genus of giant sea scorpion (order Eurypterida) that inhabited the swamps of the British Isles during the Carboniferous.

Hibbertopterus is a member of the family Hibbertopteridae, large bizarre Eurypterids found from the Upper Devonian to the end of the Permian period.[1] They were sweep feeders, inhabiting freshwater swamps and rivers, feeding by raking through the soft sediment with blades on their anterior appendages to capture small invertebrates.[2] Their morphology was so unusual that they have been thought to be an order separate from Eurypterida.[3] Recent work however confirms them to be a derived member of the suborder Stylonurina, with the genus Drepanopterus being a basal member of their superfamily.

The genus contains two species; H. scouleri from the Carboniferous of Scotland, H. hibernicus from the Carboniferous of Ireland.[4]

Description

Hibbertopterus was the largest known stylonurine eurypterid. A carapace referred to Hibbertopterus scouleri from Carboniferous Scotland measures 65 cm wide. Hibbertopterus being very wide relative to its length, the animal in question would likely have measured just short of 2 meters in length. Very deep-bodied in comparison to eurypterids of other families, the mass of Hibbertopterus would likely rival that of other giant arthropods, if not surpass them.[5]

Hibbertopterus is defined as a hibbertopterid eurypterid in which the walking legs have basal extensions but do not have longitudinal posterior grooves in any podomere. The telson was hastate, with a median keel composed of two lateral shoulders separated by a median indentation.[6]

A fossil trackway discovered in West Lothian, Scotland reveals that Hibbertopterus was capable of at least limited terrestrial locomotion.The track found was roughly six metres long and a metre wide, and suggests that the eurypterid responsible was 1.6 metres in length, consistent with other giant sizes attributed to Hibbertopterus.[7] The tracks indicate a lumbering, jerky and dragging movement. Scarps with crescent-shapes were left by the outer limbs, inner markings were made by the keeled belly and the telson carved a central groove. The slow progression and dragging of the tail indicate that the animal responsible was moving out of water.[8]

The presence of terrestrial tracks indicate that Hibbertopterus was able to survive on land at least briefly, possible due to the probability that their gills could function in air as long as they remained wet.[8] Additionally, some studies suggest that eurypterids possessed a dual respiratory system, which would allow short periods of time in terrestrial environments.[1]

Classification

It is believed that some of the genera within the Hibbertopteridae represent synonyms of each other. Four of the genera in the family, Campylocephalus, Hastimima, Dunsopterus and Vernonopterus are clearly hibbertopterids but known from very incomplete specimens. Further discoveries may point to that some of them are synonymous with either Hibbertopterus or Cyrtoctenus.[9]

Furthermore, Cyrtoctenus and Hibbertopterus might represent different ontogenetic stages of each other, where rachis would have developed in the later moult stages. This would also explain why smaller Hibbertopterus specimens are more complete than the fragmentary remains known of Cyrtoctenus, as the majority of Hibbertopterus specimens would represent exuviae whilst Cyrtoctenus specimens represent actual mortalities susceptible to scavengers.[9]

See also

References

- 1 2 Tetlie, O E (2007). "Distribution and dispersal history of Eurypterida (Chelicerata)". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 252 (3–4): 557–574. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.05.011.

- ↑ Selden, P.A., Corronca, J.A. & Hünicken, M.A (2005). "The true identity of the supposed giant fossil spider Megarachne". Biology Letters. 1 (1): 44–48. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2004.0272. PMC 1629066. PMID 17148124.

- ↑ Tollerton, V P. "Morphology, Taxonomy, and Classification of the Order Eurypterida Burmeister, 1843". Journal of Paleontology. 63: 642–657.

- ↑ Dunlop, J. A., Penney, D. & Jekel, D. 2015. A summary list of fossil spiders and their relatives. In World Spider Catalog. Natural History Museum Bern, online at http://wsc.nmbe.ch, version 16.0 http://www.wsc.nmbe.ch/resources/fossils/Fossils16.0.pdf (PDF).

- ↑ Tetlie, O. E. (2008). "Hallipterus excelsior, a Stylonurid (Chelicerata: Eurypterida) from the Late Devonian Catskill Delta Complex, and Its Phylogenetic Position in the Hardieopteridae". Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History. 49: 19–99. doi:10.3374/0079-032X(2008)49[19:HEASCE]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Jeram, Andrew J.; Selden, Paul A. (1993/01). "Eurypterids from the Viséan of East Kirkton, West Lothian, Scotland". Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 84 (3-4): 301–308. doi:10.1017/S0263593300006118. ISSN 1755-6929.

- ↑ Whyte, M A (2005). "Palaeoecology: A gigantic fossil arthropod trackway" (PDF). Nature. 438 (7068): 576. doi:10.1038/438576a. PMID 16319874.

- 1 2 "Giant Water Scorpion Walked on Land". Live Science. Retrieved 2017-12-28.

- 1 2 James C. Lamsdell, Simon J. Braddy & O. Erik Tetlie (2010). "The systematics and phylogeny of the Stylonurina (Arthropoda: Chelicerata: Eurypterida)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 8 (1): 49–61. doi:10.1080/14772011003603564.