Opioid overdose

| Opioid overdose | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms | Narcotic overdose, opioid poisoning |

| |

| A naloxone kit as distributed in British Columbia, Canada | |

| Specialty | Emergency medicine |

| Symptoms | Insufficient breathing, small pupils, unconsciousness[1] |

| Complications | Rhabdomyolysis, pulmonary edema, compartment syndrome, permanent brain damage[2][3] |

| Causes | Opioids (morphine, heroin, fentanyl, tramadol, methadone)[1][4] |

| Risk factors | Opioid dependence, use of high doses of opioids, injection of opioids, use with alcohol, benzodiazepines, or cocaine.[1][5] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Low blood sugar, alcohol intoxication, head trauma, stroke[6] |

| Prevention | Improved access to naloxone, treatment of opioid dependence[1] |

| Treatment | Supporting a person's breathing, naloxone[7] |

| Deaths | 122,100 (2015)[8] |

An opioid overdose is toxicity due to excessive opioids.[9][3] Examples of opioids include morphine, heroin, fentanyl, tramadol, and methadone.[1][4] Symptoms include insufficient breathing, small pupils, and unconsciousness.[1] Onset of symptoms depends in part on the route opioids are taken.[10] Among those who initially survive, complications can include rhabdomyolysis, pulmonary edema, compartment syndrome, and permanent brain damage.[2][3]

Risk factors for opioid overdose include opioid dependence, injecting opioids, using high doses of opioids, mental disorders, and use together with alcohol, benzodiazepines, or cocaine.[1][11][5] The risk is particularly high following detoxification.[1] Dependence on prescription opioids can occur from their use to treat chronic pain.[1] Diagnosis is generally based on symptoms.[3]

Initial treatment involves supporting the person's breathing and providing oxygen.[7] Naloxone is then recommended among those who are not breathing.[7] Given naloxone into the nose or as an injection into a muscle appears to be equally effective.[12] Among those who refuse to go to hospital following reversal, the risks of a poor outcome in the short term appear to be low.[12] Efforts to prevent deaths from overdose include improving access to naloxone and treatment for opioid dependence.[1]

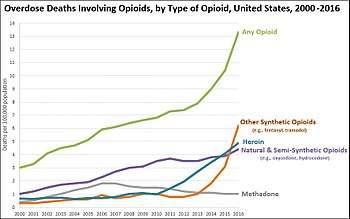

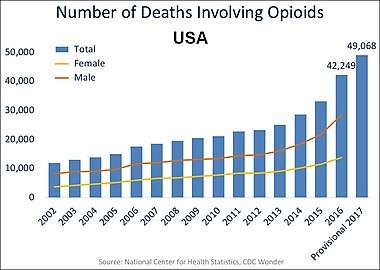

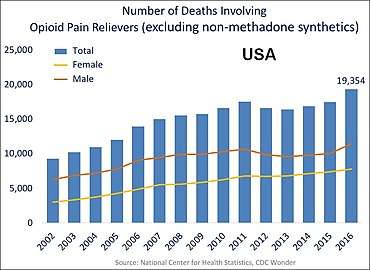

Opioid use disorders resulted in 122,000 deaths globally in 2015, up from 18,000 deaths in 1990.[8][13] In the United States over 49,000 deaths involved opioids in 2017.[5] Of those about 20,000 involved prescription opioids and 16,000 involved heroin.[5] In 2017 opioid deaths represented more than 65% of all drug overdose related deaths in the United States.[5] The opioid epidemic is believed to be in part due to assurances in the 1990s by the pharmaceutical industry that prescription opioids were safe.[4]

Signs and symptoms

Because of their effect on the part of the brain that regulates breathing, Opioids can lead to the person not breathing (respiratory depression) during overdoses and therefore result in death.[1] Opiate overdose symptoms and signs can be referred to as the "opioid overdose triad": decreased level of consciousness, pinpoint pupils and respiratory depression. Other symptoms include seizures and muscle spasms. Sometimes a person experiencing an opiate overdose can lead to such a decreased level of consciousness that he or she won't even wake up to their name being called or being shaken by another person.

Prolonged hypoxia from respiratory depression can also lead to detrimental damage to the brain and spinal cord and can leave the person unable to walk or function normally, even if treatment with naloxone is given.

Alcohol also causes respiratory depression and therefore when taken with opioids can increase the risk of respiratory depression and death.[1]

Cause

Risk factors for opioid overdose include opioid dependence, injecting opioids, using high doses of opioids, and use together with alcohol, benzodiazepines, or cocaine.[1][5] The risk is particularly high following detoxification.[1] Dependence on prescription opioids can occur from their use to treat chronic pain.[1]

Co-ingestion

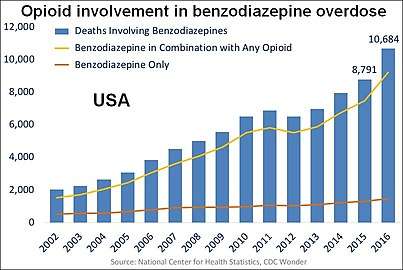

Opioid overdoses associated with a conjunction of benzodiazepines and/or alcohol use leads to a contraindicated condition.[15][16] Other CNS depressants, or "downers", muscle relaxers, pain relievers, anti-convulsants, anxiolytics (anti-anxiety drugs), treatment drugs of a psychoactive or epileptic variety or any other such drug with its active function meant to calm or mitigate neuronal signaling (barbiturates, etc.) can additionally cause a worsened condition with less likelihood of recovery cumulative to each added drug. This includes drugs less immediately classed to a slowing of the metabolism such as with GABAergics like GHB or glutamatergic antagonists like PCP or ketamine.

The top line represents the yearly number of benzodiazepine deaths that involved opioids in the US. The bottom line represents benzodiazepine deaths that did not involve opioids.[5]

The top line represents the yearly number of benzodiazepine deaths that involved opioids in the US. The bottom line represents benzodiazepine deaths that did not involve opioids.[5] Opioid involvement in cocaine overdose deaths. The yellow line (the top line in later years) represents the number of yearly cocaine deaths that also involved opioids.[5]

Opioid involvement in cocaine overdose deaths. The yellow line (the top line in later years) represents the number of yearly cocaine deaths that also involved opioids.[5]

Mechanism

Permanent brain damage may occur due to cerebral hypoxia or opioid-induced neurotoxicity.[2][17]

Prevention

Although opioid overdose accounts for the leading cause of accidental death, it can be prevented in primary care settings.[18][19] Clear protocols for staff at emergency departments and urgent care centers can reduce opioid prescriptions for individuals presenting in these settings who engage in drug seeking behaviors or who have a history of substance abuse.[20] Providers should routinely screen patients using tools such as the CAGE-AID and the Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10) to screen adults and the CRAFFT to screen adolescents aged 14–18 years.[18] Other “drug seeking” behaviors and physical indications of drug use should be used as clues to perform formal screenings.[18]

Individuals diagnosed with opioid dependence should be prescribed naloxone to prevent overdose and/or should be directed to one of the many intervention/treatment options available, such as needle exchange programs and treatment centers.[18][19] Brief motivational interviewing can also be performed by the clinician during patient visits and has been shown to improve patient motivation to change their behavior.[18][21] Despite these opportunities, the dissemination of prevention interventions in the US has been hampered by the lack of coordination and sluggish federal government response.[19]

Prescription monitoring program allow physicians to view individuals' history of prescribed opioids and other controlled substances to prevent risky behaviors, such as doctor shopping and drug diversion. These programs are operational in 49 states and the District of Columbia, and have generally been found to decrease prescribing of opioids.[22]

Regulative policies, such as Florida’s pill mill law, have also been found to decrease opioid prescribing and use, which are both correlated with opioid overdoses.[22] Florida's pill mill law addressed pill mills, or rogue pain management clinics where prescription drugs are inappropriately prescribed and dispensed, and required these clinics to register with the state, have a physician-owner, created inspection requirements, and established prescribing and dispensing requirements and prohibitions for physicians at these clinics.[22]

Treatment

Death can be prevented in individuals who have overdosed on opioids if they receive basic life support and naloxone is administered soon after the overdose occurs. Naloxone is effective at reversing the cause, rather than just the symptoms, of an opioid overdose.[23] A longer-acting variant of naloxone is naltrexone. Naltrexone is primarily used to treat opioid and alcohol dependence.

Programs to provide drug users and their caregivers with naloxone are recommended.[24] In the United States, as of 2014, more than 25,000 overdoses have been reversed.[25] Healthcare institution-based naloxone prescription programs have also helped reduce rates of opioid overdose in the US state of North Carolina, and have been replicated in the US military.[26][27] Nevertheless, scale-up of healthcare-based opioid overdose interventions are limited by providers’ insufficient knowledge and negative attitudes towards prescribing take-home naloxone to prevent opioid overdose.[28] Programs training police and fire personnel in opioid overdose response using naloxone have also shown promise.[29]

Epidemiology

Of 64,000 overdose deaths in the US in 2016,[30] opioids were involved in 42,249.[31] In 2016, the five states with the highest rates of death due to drug overdose were West Virginia (52.0 per 100,000), Ohio (39.1 per 100,000), New Hampshire (39.0 per 100,000), Pennsylvania (37.9 per 100,000) and Kentucky (33.5 per 100,000).[31][30]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 "Information sheet on opioid overdose". WHO. November 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Heroin". National Institute on Drug Abuse. July 2017. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Boyer, Edward W. (12 July 2012). "Management of Opioid Analgesic Overdose". New England Journal of Medicine. 367 (2): 146–155. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1202561. PMC 3739053. PMID 22784117.

- 1 2 3 "Opioid Overdose Crisis". National Institute on Drug Abuse. 1 June 2017. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Overdose Death Rates. By National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Note the large increase in deaths from opioids in combination with cocaine or benzodiazepines.

- ↑ Adams, James G. (2008). Emergency Medicine: Expert Consult -- Online. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. PT4876. ISBN 978-1437721294.

- 1 2 3 de Caen, AR; Berg, MD; Chameides, L; Gooden, CK; Hickey, RW; Scott, HF; Sutton, RM; Tijssen, JA; Topjian, A; van der Jagt, ÉW; Schexnayder, SM; Samson, RA (3 November 2015). "Part 12: Pediatric Advanced Life Support: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 132 (18 Suppl 2): S526–42. doi:10.1161/cir.0000000000000266. PMID 26473000.

- 1 2 GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators. (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ↑ "Commonly Used Terms Drug Overdose". www.cdc.gov. 29 August 2017. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- ↑ Malamed, Stanley F. (2007). Medical Emergencies in the Dental Office - E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 387. ISBN 978-0323075947.

- ↑ Park, TW; Lin, LA; Hosanagar, A; Kogowski, A; Paige, K; Bohnert, AS (2016). "Understanding Risk Factors for Opioid Overdose in Clinical Populations to Inform Treatment and Policy". Journal of Addiction Medicine. 10 (6): 369–381. doi:10.1097/ADM.0000000000000245. PMID 27525471.

- 1 2 Chou, Roger; Korthuis, P. Todd; McCarty, Dennis; Coffin, Phillip O.; Griffin, Jessica C.; Davis-O'Reilly, Cynthia; Grusing, Sara; Daya, Mohamud (28 November 2017). "Management of Suspected Opioid Overdose With Naloxone in Out-of-Hospital Settings". Annals of Internal Medicine. 167 (12): 867–875. doi:10.7326/M17-2224. PMID 29181532.

- ↑ GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators (17 December 2014). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–171. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- ↑ Fentanyl. Image 4 of 17. US DEA (Drug Enforcement Administration).

- ↑ "BestBets: Concomitant use of benzodiazepines in opiate overdose and the association with a poorer outcome".

- ↑ "BestBets: Concomitant use of alcohol in opiate overdose and the association with a poorer outcome".

- ↑ Cunha-Oliveira T, Rego AC, Oliveira CR (June 2008). "Cellular and molecular mechanisms involved in the neurotoxicity of opioid and psychostimulant drugs". Brain Research Reviews. 58 (1): 192–208. doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.03.002. hdl:10316/4676. PMID 18440072.

Since morphine can induce neurotoxicity (Hu et al., 2002; Mao et al., 2002; Lim et al., 2005), it may contribute to the neurotoxic effects of heroin. However, we showed that 6-MAM and morphine do not contribute to street heroin neurotoxicity in cultured cortical neurons (Cunha-Oliveira et al., 2007). In accordance, a recent study suggests that heroin has a higher neurotoxic potential in comparison with morphine (Tramullas et al., 2008).

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bowman S, Eiserman J, Beletsky L, Stancliff S, Bruce RD (2013). "Reducing the health consequences of opioid addiction in primary care". Am J Med. 126 (7): 565–71. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.11.031. PMID 23664112. In press

- 1 2 3 Beletsky L, Rich JD, Walley AY (2012). "Prevention of Fatal Opioid Overdose". JAMA. 308 (18): 1863–1864. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.14205. PMC 3551246. PMID 23150005.

- ↑ "Emergency Department and Urgent Care Clinicians Use Protocol To Reduce Opioid Prescriptions for Patients Suspected of Abusing Controlled Substances". Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2014-03-12. Retrieved 2014-03-14.

- ↑ Zahradnik A, Otto C, Crackau B, et al. (2009). "Randomized controlled trial of a brief intervention for problematic prescription drug use in non-treatment-seeking patients". Addiction. 104 (1): 109–117. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02421.x. PMID 19133895.

- 1 2 3 Rutkow, Lainie; Chang, Hsien-Yen; Daubresse, Matthew; Webster, Daniel W.; Stuart, Elizabeth A.; Alexander, G. Caleb (2015). "Effect of Florida's Prescription Drug Monitoring Program and Pill Mill Laws on Opioid Prescribing and Use". JAMA Internal Medicine. 175 (10): 1642–1649. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.3931. ISSN 2168-6114. PMID 26280092.

- ↑ Etherington, J; Christenson, J; Innes, G; Grafstein, E; Pennington, S; Spinelli, JJ; Gao, M; Lahiffe, B; et al. (2000). "Is early discharge safe after naloxone reversal of presumed opioid overdose?". CJEM. 2 (3): 156–62. PMID 17621393.

- ↑ Community management of opioid overdose (PDF). World Health Organization. 2014. ISBN 9789241548816.

- ↑ Wheeler, E; Jones, TS; Gilbert, MK; Davidson, PJ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, (CDC). (19 June 2015). "Opioid Overdose Prevention Programs Providing Naloxone to Laypersons - United States, 2014". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 64 (23): 631–5. PMC 4584734. PMID 26086633.

- ↑ Albert, Su; Brason Ii, Fred W.; Sanford, Catherine K.; Dasgupta, Nabarun; Graham, Jim; Lovette, Beth (2011). "Project Lazarus: Community-Based Overdose Prevention in Rural North Carolina". Pain Medicine. 12: S77–85. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01128.x. PMID 21668761.

- ↑ Beletsky, Leo; Burris, Scott C.; Kral, Alex H. (July 21, 2009). "Closing Death's Door: Action Steps to Facilitate Emergency Opioid Drug Overdose Reversal in the United States". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1437163. SSRN 1437163.

- ↑ Beletsky, Leo; Ruthazer, Robin; MacAlino, Grace E.; Rich, Josiah D.; Tan, Litjen; Burris, Scott (2006). "Physicians' Knowledge of and Willingness to Prescribe Naloxone to Reverse Accidental Opiate Overdose: Challenges and Opportunities". Journal of Urban Health. 84 (1): 126–36. doi:10.1007/s11524-006-9120-z. PMC 2078257. PMID 17146712.

- ↑ Lavoie D. (April 2012). "Naloxone: Drug-Overdose Antidote Is Put In Addicts' Hands". Huffington Post.

- 1 2 National Center for Health Statistics. "Provisional Counts of Drug Overdose Deaths, as of 8/6/2017" (PDF). United States: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Source lists US totals for 2015 and 2016 and statistics by state.

- 1 2 Drug Overdose Death Data. CDC Injury Center. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The numbers for each state are in the data table below the map.

- ↑ Chart from Opioid Data Analysis and Resources. Drug Overdose. CDC Injury Center. Click on "Rising Rates" tab. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Drug-related death statistics. |