Herbert Maryon

| Herbert Maryon | |

|---|---|

With his reconstruction of the Sutton Hoo helmet, ca. 1951. The image to Maryon's left depicts the helmet from Vendel 14; that on his right shows plate 1 from Greta Arwidsson's 1942 work on Valsgärde 6, and depicts the helmet from said grave. | |

| Born |

9 March 1874 London, England |

| Died |

14 July 1965 (aged 91) Edinburgh, Scotland |

| Nationality | English |

| Occupation | Sculptor, metalsmith, conservator-restorer |

| Relatives | John, Edith, George, Mildred, Violet (siblings) |

| Signature | |

|

| |

Herbert James Maryon, OBE, FSA, FIIC (9 March 1874 – 14 July 1965) was a British sculptor, goldsmith, and authority on ancient metalwork. He served as director of the Keswick School of Industrial Art, a teacher of sculpture at Reading University, and Master of Sculpture at Durham University. From 1944 to 1961 he was a Technical Attaché at the British Museum, where his conservation work on the Sutton Hoo ship burial led to his appointment as an Officer of the Order of the British Empire.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14]

Personal life

Herbert Maryon was the third of six surviving children born to John Simeon Maryon and Louisa Maryon (née Church).[15][16][17] He had both an older brother, John Ernest, and an older sister, Louisa Edith, the latter of whom preceded him in his vocation as a sculptor.[18] One brother and three sisters would follow—in order, George Christian, Flora Mabel, Mildred Jessie, and Violet Mary—although Flora Maryon, born in 1878, would die in her second year.[19] After receiving his general education at The Lower School of John Lyon,[20] Herbert Maryon studied from 1896 to 1900 at the Polytechnic (probably Regent Street[2]), The Slade, Saint Martin's School of Art, and, under the tutelage of Alexander Fisher[21] and William Lethaby,[22] the Central School of Arts and Crafts.[2][20] His schooling included a one-year silversmithing apprenticeship in 1898, at C. R. Ashbee's Essex House Guild of Handicrafts.[20][2]

A daughter, Kathleen Rotha Maryon,[23][24][25] was born to his first wife Annie Elizabeth Maryon (née Stones),[6] to whom he was married from July 1903[26][27] until her death on 8 February 1908. A second Marriage, to Muriel Dore Wood[6] in September 1920,[28] led to the births of son John and daughter Margaret.[10][29] Herbert Maryon lived for the majority of his life in London, before dying in his 92nd year at a nursing home in Edinburgh.[10][30][31]

Sculpture

From 1900 until 1939, Maryon held various positions teaching sculpture, design, and metalwork.[2] During this time he created and exhibited many of his own works.[2] Several of his works were also exhibited before he finished his education.[2] At the end of 1899 he displayed a silver cup and a shield of arms with silver cloisonné at the sixth exhibition of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, an event held at the New Gallery that also included a work by Maryon's sister.[32] The exhibition was reviewed by The International Studio, with his work singled out as "agreeable".[33]

Teacher of sculpture, 1907–39

From 1907 until 1939, Maryon taught sculpture, first at the University of Reading and then at Durham University's Armstrong College.[20][6][34][35] At Reading he was teacher of metalwork, modelling, and casting; at Durham, he was both master of sculpture, and lecturer in anatomy and the history of sculpture.[20][34][35] During World War I Maryon worked at Reading with another instructor, Charles Albert Sadler, to create a centre to train munition workers in machine tool work.[2][20] Maryon began this work in 1915, officially as organising secretary and instructor at the Ministry of Munitions Training Centre, with no engineering school to build from.[20] By 1918 the centre had five staff members, could accommodate 25 workers at a time, and had trained more than 400.[20] Based on this work, Maryon was elected to the Institution of Mechanical Engineers on 6 March 1918.[2][20]

Following the war, Maryon designed several memorials.[36][37] He designed the East Knoyle War Memorial and the Mortimer War Memorial, unveiled in 1920 and 1921 respectively.[38][39][36] Three years later witnessed the unveiling of his design for the University of Reading war memorial, a clocktower on the London Road Campus.[37][40]

From 1927 to 1939 Maryon taught sculpture at Armstrong College, then part of Durham University.[34][35] While there he published his second book, Modern Sculpture: Its Methods and Ideals.[41] Maryon wrote that his aim was to discuss modern sculpture "from the point of view of the sculptors themselves", rather than from an "archaeological or biographical" perspective.[42] The book received mixed reviews.[43] Maryon's decision to treat criticism as secondary to intent meant grouping together artworks of unequal quality.[44] Criticisms attacked his taste, with the New Statesman and Nation claiming that "He can enjoy almost anything, and among his 350 odd illustrations there are certainly some camels to swallow",[45] The Bookman that "All the bad sculptors ... will be found in Mr. Maryon's book ... Most of the good sculptors are here as well (even Henry Moore), but all are equal in Mr. Maryon's eye",[46] and The Spectator that "The few good works which have found their way into the 356 plates look lost and unhappy."[47] Maryon responded with explanations of his purpose,[48][49] saying that "I do not admire all the results, and I say so",[50] and to one review in particular that "I believe that the sculptors of the world have a wider knowledge of what constitutes sculpture than your reviewer realizes."[51][52] Other reviews praised Maryon's academic approach.[53][49] The Times stated that "his book is remarkable for its extraordinary catholicity, admitting works which we should find it hard to defend ... with works of great merit", yet added that "By a system of grouping, however, according to some primarily aesthetic aim ... their inclusion is justified."[44] The Manchester Guardian praised Maryon for "a degree of natural good sense in his observations that cannot always be said to characterise current art criticism", and stated that "his critical judgments are often penetrating."[54]

At Durham, like at Reading, Maryon was commissioned to create works of art.[55][14] These included at least two plaques, memorialising George Stephenson,[56][55] and Sir Charles Parsons.[57][14][note 1] Maryon also sculpted the Statue of Industry for the 1929 North East Coast Exhibition, a world's fair held at Newcastle upon Tyne.[59][60] Depicting a woman with cherubs at her feet, the statue was described by Maryon as "represent[ing] industry as we know it in the North-east—one who has passed through hard times and is now ready to face the future, strong and undismayed."[60] The statue was the subject of "adverse criticism", reported The Manchester Guardian; on the night of October 25 "several hundred students of Armstrong College" tarred and feathered the statue, and required 80 police officers to be dispersed.[59]

Maryon's time at Armstrong coincided with an interest in archaeology.[61]

British Museum, 1944–61

On 11 November 1944 Maryon was recruited out of retirement by the Trustees of the British Museum to serve as a Technical Attaché.[62] Maryon was tasked with the conservation and reconstruction of material from the Sutton Hoo ship-burial,[63][64] an excavation in which he had previously expressed interest; as early as 1941, he wrote a prescient letter about the preservation of the ship impression to the museum's Keeper of British and Medieval Antiquities.[65][note 2] Nearly four years after his letter, he was assigned "the real headaches - notably the crushed shield, helmet and drinking horns."[75] Composed in large part of iron, wood and horn, these items had decayed in the 1,300 years since their burial and left only fragments behind; the helmet, for one, had corroded and then smashed into more than 500 pieces.[76] "[M]inute work requiring acute observation and great patience," these efforts occupied several years of Maryon's career.[5] Much of Maryon's work has seen subsequent revision, "but by carrying out the initial cleaning, sorting, and mounting of the mass of the fragmentary and fragile material he preserved it, and in working out his reconstructions he made explicit the problems posed and laid the foundations upon which fresh appraisals and progress could be based when fuller archaeological study became possible."[77] In 1949 Maryon was admitted as a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries,[78][79] and in 1956 his Sutton Hoo work "brought him his O.B.E."[5][80] Asked by the Queen what he did as she awarded him the medal, Maryon responded "Well, Ma'am, I am a sort of back room boy at the British Museum."[81] Maryon continued restoration work at the British Museum, including on a Roman helmet found in Homs, before retiring—for a second time—at the age of 87.[7][8][1][4][82]

Sutton Hoo helmet

From 1946 to 1947,[83] Maryon undertook the first restoration of the fragmented Sutton Hoo helmet, then "the only known example of a decorated Anglo-Saxon helmet."[84][note 3] Maryon's work was "generally acclaimed," and both academically and culturally influential.[84] It stayed on display for over 20 years,[84][88] with photographs[89][90][91] making their way television programmes,[92] newspapers, and "every book on Anglo-Saxon art and archaeology";[84] in 1951 a young Larry Burrows was dispatched to the British Museum by Life, which subsequently published a full page photograph of the helmet alongside a photo of Maryon.[93][94] Over the "fifteen years since Maryon's time conservation techniques and scientific possibilities . . . advanced dramatically,"[95] however, while "greater knowledge about Saxon and Vendel helmets became available"[96] and limitations of Maryon's reconstruction—notably its diminished size, gaps in afforded protection, and lack of a moveable neck guard—became apparent;[84][note 4] so too were more helmet fragments discovered during the 1965–69 re-excavation of Sutton Hoo.[99][69][100][101][102][103] In 1970 it was "taken to pieces for re-examination," and after eighteen months a second restoration completed.[104] Nevertheless, "[m]uch of Maryon's work is valid. The general character of the helmet was made plain."[88] Just as minor errors in the second reconstruction were discovered while forging the 1973 Royal Armouries replica,[105][106][note 5] "[i]t was only because there was a first restoration that could be constructively criticized, that there was the impetus and improved ideas available for a second restoration."[96] In executing a first reconstruction that was "physically reversible" and retained evidence through the "limited . . . cleaning of the mineralized iron fragments,"[109] Maryon's true contribution to the Sutton Hoo helmet was in creating a credible first rendering that allowed for the critical examination leading to the second, current, reconstruction.[77] As Rupert Bruce-Mitford, then Assistant Keeper of the Department of British Antiquities at the British Museum,[110][111][112] wrote in 1947, "[a]rchaeology is indebted in Mr. Maryon for re-creating the helmet out of hundreds of crumbly fragments, most of which were unintelligible without prolonged and careful study."[113]

_-_Taf._1_-_Helmet.png)

Though "[o]ne of the most important objects found"[85] in "the richest find ever made on British soil,"[115] the fragmentary state of the Sutton Hoo helmet caused it to go at first unnoticed. "No photographs had been taken of [the fragments] during excavation as their importance had not been realized at the time."[116] The excavation diary of Charles Phillips merely mentioned that on 28 July 1939 "crushed remains of an iron helmet were found four feet east of the shield boss on the north side of the central deposit";[117][118] whereas photographs of the shield in situ allowed "Dr Plenderleith to pick out from among the fragments of bronze and iron those pieces which made up the shield-grip,"[119] no such contextual evidence survived for the helmet. Stalled for six years by World War II, when it reached Maryon's workbench in 1945 the "task of restoration was thus reduced to a jigsaw puzzle without any sort of picture on the lid of the box,"[85] and, "as it proved, a great many of the pieces missing."[104] Maryon was left to base his reconstruction "exclusively on the information provided by the surviving fragments, guided by archaeological knowledge of other helmets."[104]

Maryon's "[w]ork on the helmet was full-time and continuous and took six months."[113] Much like with the second reconstruction, efforts began with a "process of familiarisation"[120] with the various fragments;[116] each piece was traced and detailed on a "piece of stiff card," until after "a long while" reconstruction could commence.[116] For this, Maryon formed "a head of normal size" from plaster, then "padded the head out above the brows to allow for the thickness of the lining which a metal helmet would naturally require."[121] The fragments of the skull cap were then initially stuck to the head with plasticine, or, if thicker, placed into spaces cut into the head. Finally, "strong white plaster" was used to permanently affix the fragments, and, mixed with brown umber, fill in the gaps between pieces.[121] Meanwhile, the fragments of the cheek guards, neck guard, and visor were placed onto shaped, plaster-covered wire mesh, then affixed with more plaster and joined to the cap.[122] The reconstruction finished, Maryon published a paper detailing the helmet in a 1947 issue of Antiquity.[123]

Along with giving shape to the first decorated helmet found from the Anglo-Saxon period, Maryon's reconstruction correctly identified both the five designs depicted on its exterior, and the helmet's method of construction. The helmet was made of sheet iron, then "covered with sheets of very thin tinned bronze, stamped with patterns, and arranged in panels."[116] The patterns were formed from dies carved in relief, while the panels were "framed by lengths of moulding . . . swaged from strips of tin," themselves "fixed in place by bronze rivets," and gilded.[124] Meanwhile, "the free edges of the helmet were protected by a U-shaped channel of gilt bronze, clamped on, and held in position by narrow gilt bronze ties, riveted on."[116] Although likely not more than "educated guess[es]," Maryon's statements were largely confirmed by scientific analysis carried out after completion of the second reconstruction.[125][note 6]

After Sutton Hoo

Maryon's work on the Sutton Hoo finds carried him to 1950, at which point Plenderleith decided that the work had been finished to the extent possible, and that the space in the research laboratory was needed for other purposes.[127] Maryon continued working at the museum until 1961, turning his attention to other matters.[5] This included, in 1955,[128] the restoration of another helmet.[129][130] Found in the modern-day city of Homs in 1936,[131] after undergoing several failed restorations the Roman Emesa helmet was brought to the British Museum.[129][130]

Publications

Maryon published two books: Metalwork and Enamelling, still in publication in its fifth edition,[133] and Modern Sculpture. The former work included a critique of the celebrated goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini, republished a decade later in The Jewelers' Circular,[134] in which Maryon termed him "one of the very greatest craftsmen of the sixteenth century, but ... a very poor artist."[135] For this "dispassionate appraisal", Maryon was remembered as "a discerning critic" at his death. He also authored chapters in volumes one and two of Charles Singer's A History of Technology series, and of some thirty archaeological and technical papers.[4][6][34][35] Several of Maryon's earlier papers described his restorations of the shield and helmet from the Sutton Hoo burial,[136][123] while a 1948 paper introduced the term pattern welding to describe a method of strengthening and decorating iron and steel by welding into them twisted strips of metal.[137][138]

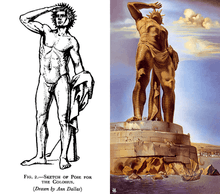

In 1953 and 1954, a talk and paper on the Colossus of Rhodes received international attention for suggesting that the statue was hollow, and aside the harbor rather than astride it.[note 7] Made of hammered bronze plates less than a sixteenth of an inch thick, he suggested, it would have been supported there by a hanging piece of drapery acting as a third point of support.[192][132] If "great ideas," neither "proved to be truly convincing";[132] in 1957, D. E. L. Haynes, then the Keeper of Greek and Roman Antiquities at the British Museum,[193][194] suggested that Maryon's theory of hammered bronze plates relied on an errant translation of a primary source.[195][note 8] Maryon's view was nevertheless influential, likely shaping Salvador Dalí's 1954 surrealist imagining of the statue, The Colossus of Rhodes. "Not only the pose, but even the hammered plates of Maryon's theory find [in Dalí's painting] a clear and very powerful expression."[132]

Later years

Maryon finally left the British Museum in 1961,[5] a year after his official retirement.[82] Before his departure he had been planning a trip around the world,[82][4] and at the end 1961 he left for Fremantle, Australia, arriving on 1 January 1962.[197] In Perth he visited a brother he had not seen in 60 years.[129][130][197] From Australia Maryon departed for San Francisco,[82] arriving on 15 February.[129][130] Much of his North American tour was done with buses and cheap hotels,[82][4] for, as a colleague would recall, Maryon "liked to travel the hard way—like an undergraduate—which was to be expected since, at 89, he was a young man."[82]

For the American stage in particular of his world trip, Maryon devoted much of his time to visiting museums and the study of Chinese magic mirrors,[1] a subject he had turned to some two years before.[129][130] By the time he reached Kansas City, Missouri, where he was written up in The Kansas City Times, he had listed 526 examples in his notebook.[129][130] His trip also included guest lectures, such as his talk Metal Working in the Ancient World at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology on 2 May 1962,[198] and when he came to New York City a colleague later said that "he wore out several much younger colleagues with an unusually long stint devoted to a meticulous examination of two large collections of pre-Columbian fine metalwork, a field that was new to him."[1] Maryon scheduled the trip to end in Toronto, where his son John Maryon, a civil engineer, lived.[129][130][10]

Notes

- ↑ The Parsons plaque was placed on display at C. A. Parsons and Company.[58] Sometime after 2003 the building was demolished and the plaque was donated to the Discovery Museum, where as of 2016 there were plans to place it on display.[58]

- ↑ Maryon's letter was addressed to T. D. Kendrick, who would become Director of the museum in 1950.[66][67][68] Dated 6 January 1941, it read:

"There is a question about the Sutton Hoo ship which has been rather on my mind. There exist many photographs of the ship, taken from many angles, and they provide much information as to its structure and general appearance. But has anything been done to preserve the actual form of the vessel--full size?

Such an operation was not carried out at the time, due largely to time constraints imposed by World War II—impending during the original 1939 excavation, and in full swing by the time of Maryon's letter.[69][70] When an impression was, however, taken during the 1965–69 excavations of Sutton Hoo,[71][72][73][74] much the same methods that Maryon proposed were adopted.[70]

The Viking ships in their museum in Scandinavia are most impressive, for they are surviving representatives of the actual vessels which played so great a part in the early history of Western Europe. The Sutton Hoo ship is our only representative in this class. I believe that all the timbers have perished, but the form remains--traced in the earth.

That form could be preserved in a plaster cast. I have given some thought to the making of large casts for I have done figures up to 18 feet in height. The work could be done in the following manner: a light steel girder would be constructed, running the full length of the ship, but built in quite short sections. This would not rise above the level of the gunwale at any point but would follow the general curve of the central section of the vessel. It would extend right down to the keel, and would support all the lateral frames. The outer skin, which would preserve the actual external form of the vessel, would be of the usual canvas and plaster work. It would be cast in sections, each perhaps extending along five feet of the length and from keel to gunwale on one side. All sections would be assembled by bolting the frames together. Any roughness of surface due to accidental irregularities in the existing earth matrix could be removed. If it were desired to illustrate the inner structure of the vessel also, I think that that might be shown by constructing a wooden model on a reduced scale.

Such a cast as that suggested above would be a very important document for the history of the time and it would provide a valuable introduction to Sutton Hoo's splendid array of furnishings."[65] - ↑ Two points bear clarification. First, the modifier "decorated" refers to the fact that an undecorated Anglo-Saxon helmet, the Benty Grange helmet, was discovered in Derbyshire in 1848. This helmet was "of a different type, lacking the elaborate decoration of the Sutton Hoo example and with its cap constructed largely from plates of horn."[85] Second, many, including Maryon,[86][87] believe that the Sutton Hoo helmet is of Swedish, rather than Anglo-Saxon, origin.[85] It is unclear whether Williams, by terming it an "Anglo-Saxon helmet," is here expressing the contrary view that the helmet was instead manufactured in Great Britain, or simply referring to its place of later use and discovery.

- ↑ Rupert Bruce-Mitford suggested that Maryon's reconstruction "was soon criticized, though not in print, by Swedish scholars and others."[85] At least one scholar, however, did publish "minor criticism of some of the details of the reconstruction."[97] In a 1948 article by Sune Lindqvist—translated into English by Bruce-Mitford himself—the Swedish professor wrote that "[t]he reconstruction of the Sutton Hoo helmet . . . needs revision in certain respects." Nonetheless, his only specific criticism was that the face-mask was "set somewhat awry in the reconstruction."[98]

- ↑ The errors in the second reconstruction were comparatively minor,[104] consisting primarily of slight errors in placement.[105] "The chief of these related to the neck-guard. The profile view of the reconstruction shows that the projecting corner of the cheek-piece and the neck-guard, which adjoin, are not at the same level. This has been corrected in the Tower replica, as it became apparent that the neck-guard must have fitted inside the cap. This off-setting in the line of cap and neck-guard lifts the latter slightly and allows it to ride up, bringing the corners to the same level. This provides the smooth curves at the top of the openings to accommodate the lift of the shoulder or arm."[107] Additionally, while the replica helmet has an interlace pattern of identical length repeated on both the top and bottom of the neck guard, the second reconstruction gives substantially more length to the bottom portion. The fragments from the middle of the neck guard with horizontal fluted strips separating the top and bottom patterns are placed too high, and are thus slightly out of alignment with the fluted strips seen on the fragments on the right (dexter) side of the neck guard. "This should be adjusted to equal lengths above and below as shown in the Tower replica."[108]

- ↑ The nature of the moulding separating the panels, however, remains unclear. Maryon suggested they were swaged from tin and gilded,[124] while Bruce-Mitford suggested they were made of bronze.[83] The later analysis found results which were perhaps contradictory, yet themselves internally contradictory. A subsurface sample of the moulding "suggest[ed] that the original metal was tin," (Maryon's theory) while a surface sample showed an "ε-copper/tin compound (Cu3Sn)" and thus "suggest[ed] instead,"[126] because of a similar process observed on the shield,[125] "that the surface of a bronze alloy containing at least 62% of copper had been coated with tin and heated."[126] Additionally, a surface sample taken near the crest had a trace of mercury, suggestive of a fire-gilding process that requires a temperature at least 128 °C above the melting point of tin.[126] An alloy containing at least 20% copper would thus be needed to sufficiently raise the melting point of the tin during the gilding process, a reality further inconsistent with the results of the subsurface sample of moulding.[126] As to swageing, "if the strips [of moulding] were of high tin alloy throughout, swageing would be impossible as copper/tin alloys containing more than 20% of tin are very brittle," while an alloy containing less than 25% tin would no longer replicate the white colour of the helmet.[126] Although the subsurface sample supports Maryon's theory of swaged tin—though not of universally gilded mouldings, which as reflected in the 1973 replica helmet were only found next to the crest—it contradicts the theory suggested by the surface sample, i.e., a copper alloy with a high tin content that was not swaged.

- ↑ AP stories: .[139][140][141][142][143][144][145][146][147][148][149][150][151][152][153][154][155][156][157][158][159][160][161][162][163][164][165][166][167][168][169][170][171] Non-AP stories: .[172][173][174][175][176][177][178][179][180][181][182][183][184][185][186][187][188][189] These newspapers reference an account read to the Society of Antiquaries of London on 3 December 1953.[190] Maryon published the paper, entitled The Colossus of Rhodes, in The Journal of Hellenic Studies in 1956.[191]

- ↑ Maryon used J. C. Orelli's translation of Philo of Byzantium, which Haynes argued "is frequently misleading."[196] Using Rudolf Hercher's translation, Haynes suggested that "Έπιχωνεύειν is a key word for the whole of Philo's description. An unfortunate slip in the translation used by Maryon confuses it with ἐπιχωννύειν 'to fill up' and so destroys the sense of the passage. Έπιχωνεύειν means 'to cast upon' the part already cast, and that implies casting in situ. It is contrasted with ἐπιθεῖναι 'to place upon', which would imply that the casting was done at a distance. Since in 'casting upon' the molten metal which was to form the new part would presumably have come into direct contact with the existing part, fusion (i.e. 'casting on' in the technical sense) would probably have resulted."[196]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Easby, Jr. 1966.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Mapping Sculpture 2011a.

- ↑ Mapping Sculpture 2011b.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Schweppe 1965b.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bruce-Mitford 1965.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Who Was Who 2014.

- 1 2 Huey 1962a, p. 1.

- 1 2 Huey 1962b, p. 2.

- ↑ Daily Telegraph 1965a.

- 1 2 3 4 Daily Telegraph 1965b.

- ↑ Ottawa Journal 1965.

- ↑ Bruce 2001.

- ↑ Crouch & Barnes.

- 1 2 3 The Times 1932.

- ↑ Maryon 1895, pp. 9–10.

- ↑ England Census 1891.

- ↑ England Birth Index 1874.

- ↑ Paull, John (2018) A Portrait of Edith Maryon: Artist and Anthroposophist, Journal of Fine Arts, 1(2):8-15.

- ↑ Maryon 1895, p. 10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Institution of Mechanical Engineers 1918.

- ↑ Bruce 2001, p. 54.

- ↑ International Studio 1908, p. 342.

- ↑ Lancashire Parish Clerks.

- ↑ England Census 1911.

- ↑ The Times 1929.

- ↑ England Marriages 1903.

- ↑ England Marriage Index 1903.

- ↑ England Marriage Index 1920.

- ↑ Winnipeg Free Press 2005.

- ↑ Brandon Sun 1965.

- ↑ England Probate 1965.

- ↑ Arts & Crafts Exhibition Catalogue 1899, pp. 19, 49, 91, 136.

- ↑ H. 1899, pp. 269–270.

- 1 2 3 4 Studies in Conservation 1960a.

- 1 2 3 4 Studies in Conservation 1960b.

- 1 2 Mortimer War Memorial.

- 1 2 Reading University Memorial.

- ↑ Western Gazette 1920.

- ↑ Historic England East Knoyle.

- ↑ Historic England Reading.

- ↑ Maryon 1933a.

- ↑ Maryon 1933a, p. v.

- ↑ Ferrari 1934.

- 1 2 Marriott 1934.

- ↑ New Statesman and Nation 1933.

- ↑ Grigson 1933, p. 214.

- ↑ The Spectator 1934.

- ↑ Maryon 1933b.

- 1 2 The Scotsman 1933.

- ↑ Maryon 1933c.

- ↑ Maryon 1934, p. 190.

- ↑ B. 1934b.

- ↑ The Connoisseur 1934.

- ↑ B. 1934a.

- 1 2 Institution of Mechanical Engineers 1931, pp. 249–250.

- ↑ Lake Wakatip Mail 1929.

- ↑ The Gazette 1933.

- 1 2 Friends of Discovery Museum 2016.

- 1 2 Manchester Guardian 1933a.

- 1 2 Manchester Guardian 1933b.

- ↑ Knutsen & Knutsen 2005, pp. 21, 100.

- ↑ Bruce-Mitford 1975, p. 228.

- ↑ Financial Times 1971.

- ↑ The Times 1973.

- 1 2 Bruce-Mitford 1975, pp. 228–229.

- ↑ Sorensen.

- ↑ The Times 1979.

- ↑ British Museum.

- 1 2 Bruce-Mitford 1974a, p. 170.

- 1 2 Bruce-Mitford 1975, p. 229.

- ↑ Bruce-Mitford 1968.

- ↑ Bruce-Mitford 1974a, pp. 170–174.

- ↑ van Geersdaele 1969.

- ↑ van Geersdaele 1970.

- ↑ Bruce-Mitford 1989a.

- ↑ Williams 1992, p. 77.

- 1 2 Bruce-Mitford 1983a, p. xliii.

- ↑ Proceedings 1949a.

- ↑ Proceedings 1949b.

- ↑ London Gazette 1956, p. 3113.

- ↑ Maryon 1971, p. iii.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Schweppe 1965a.

- 1 2 Bruce-Mitford 1978, p. 146.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Williams 1992, p. 74.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bruce-Mitford 1972, p. 120.

- ↑ Maryon 1946, p. 28.

- ↑ The Times 1946.

- 1 2 Bruce-Mitford 1972, p. 121.

- ↑ Green 1963.

- ↑ Grohskopf 1970.

- ↑ Wilson 1960.

- ↑ Marzinzik 2007, pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Life 1951.

- ↑ Gerwardus 2011.

- ↑ Bruce-Mitford 1970, p. viii.

- 1 2 Caple 2000, p. 133.

- ↑ Green 1963, p. 69.

- ↑ Lindqvist 1948, p. 136.

- ↑ Bruce-Mitford 1968, p. 36.

- ↑ Bruce-Mitford 1975, p. 279.

- ↑ Bruce-Mitford 1975, p. 332.

- ↑ Bruce-Mitford 1975, p. 335.

- ↑ Bruce-Mitford 1978, p. 156.

- 1 2 3 4 Bruce-Mitford 1978, p. 140.

- 1 2 Bruce-Mitford 1978, p. 181.

- ↑ Bruce-Mitford 1974b, p. 285.

- ↑ Bruce-Mitford 1978, p. 181 (references omitted).

- ↑ Bruce-Mitford 1978, p. 176 n.1.

- ↑ Caple 2000, p. 134.

- ↑ Bruce-Mitford 1947, p. 3.

- ↑ Biddle 2015.

- ↑ The Times 1994.

- 1 2 Bruce-Mitford 1947, p. 24.

- ↑ Arwidsson 1942, p. Taf. 1.

- ↑ Williams 1992, p. 73.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Maryon 1947, p. 137.

- ↑ Bruce-Mitford 1975, p. 742.

- ↑ Bruce-Mitford 1978, p. 138.

- ↑ Maryon 1946, p. 21.

- ↑ Williams 1992, p. 78.

- 1 2 Maryon 1947, p. 144.

- ↑ Williams 1992, pp. 74–75.

- 1 2 Maryon 1947.

- 1 2 Maryon 1947, p. 138.

- 1 2 Bruce-Mitford 1978, p. 226.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bruce-Mitford 1978, p. 227.

- ↑ Bruce-Mitford 1989b, p. 14.

- ↑ Illustrated London News 1955.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Huey 1962a.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Huey 1962b.

- ↑ Seyrig 1952, p. 66.

- 1 2 3 4 de Callataÿ 2006, p. 54.

- ↑ Dover Publications.

- ↑ Maryon 1922b.

- ↑ Maryon 1912, p. 290.

- ↑ Maryon 1946.

- ↑ Maryon 1948a.

- ↑ Maryon 1960a, p. 26.

- ↑ Austin Statesman 1953.

- ↑ Corpus Christi Caller 1953.

- ↑ Fresno Bee 1953.

- ↑ Lubbock Journal 1953.

- ↑ Macon Chronicle Herald 1953.

- ↑ Mason Globe-Gazette 1953.

- ↑ Moberly Monitor-Index 1953.

- ↑ Plain Speaker 1953.

- ↑ Spokane Chronicle 1953.

- ↑ Tucson Citizen 1953.

- ↑ Vernon Record 1953.

- ↑ Chicago Tribune 1953.

- ↑ Abilene Reporter-News 1953.

- ↑ Council Bluffs Nonpareil 1953a.

- ↑ Indiana Gazette 1953a.

- ↑ Indiana Gazette 1953b.

- ↑ San Bernardino Sun 1953.

- ↑ Washington Post 1953.

- ↑ Council Bluffs Nonpareil 1953b.

- ↑ Odessa American 1953.

- ↑ Santa Cruz Sentinel 1953.

- ↑ Sedalia Democrat 1953.

- ↑ Progress-Index 1953.

- ↑ Eagle 1953.

- ↑ News Leader 1953.

- ↑ News Journal 1953.

- ↑ Indianapolis News 1953a.

- ↑ Petaluma Argus-Courier 1953.

- ↑ St. Louis Post-Dispatch 1953.

- ↑ Des Moines Tribune 1953.

- ↑ Reno Gazette 1953.

- ↑ Battle Creek Enquirer 1953a.

- ↑ Daily Times 1953.

- ↑ Oakland Tribune 1953.

- ↑ Minneapolis Tribune 1953.

- ↑ Detroit Free Press 1953.

- ↑ Battle Creek Enquirer 1953b.

- ↑ Nashville Tennessean 1953.

- ↑ Hartford Courant 1953.

- ↑ Indianapolis News 1953b.

- ↑ Muncie Evening Press 1953.

- ↑ Corsicana Daily Sun 1953.

- ↑ Kansas City Times 1953.

- ↑ Hammond Times 1954.

- ↑ Tucson Citizen 1954.

- ↑ Anderson Herald 1954.

- ↑ Alton Telegraph 1954.

- ↑ Chautauqua Farmer 1954.

- ↑ Greeley Tribune 1954.

- ↑ Wausau Daily Record-Herald 1954.

- ↑ Scarre 1991.

- ↑ Proceedings 1954.

- ↑ Maryon 1956.

- ↑ Maryon 1956, p. 72.

- ↑ Williams 1994.

- ↑ Monuments Men Foundation.

- ↑ Haynes 1957.

- 1 2 Haynes 1957, p. 311.

- 1 2 Fremantle Passenger Lists 1962.

- ↑ The Tech 1962.

Bibliography

Works by Maryon

Books

- Maryon, Herbert (1912). Metalwork and Enamelling. London: Chapman & Hall.

- Maryon, Herbert (1923). Metalwork and Enamelling (2nd ed.). London: Chapman & Hall.

- Maryon, Herbert (1954). Metalwork and Enamelling (3rd ed.). London: Chapman & Hall.

- Maryon, Herbert (1959). Metalwork and Enamelling (4th ed.). London: Chapman & Hall.

- Maryon, Herbert (1971). Metalwork and Enamelling (5th ed.). New York: Dover. ISBN 0-486-22702-2.

- Maryon, Herbert (1933a). Modern Sculpture: Its Methods and Ideals. London: Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons.

- Maryon, Herbert & Plenderleith, H. J. (1954). "Fine Metal-Work". In Singer, Charles; Holmyard, E. J. & Hall, A. R. A History of Technology: From Early Times to Fall of Ancient Empires. 1. London: Oxford University Press. pp. 623–662.

- Maryon, Herbert (1956). "Fine Metal-Work". In Singer, Charles; Holmyard, E. J.; Hall, A. R. & Williams, Trevor I. A History of Technology: The Mediterranean Civilizations and the Middle Ages. 2. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 449–484.

Articles

- Maryon, Herbert (October 1905). "Early Irish Metal Work". The Art Workers' Quarterly. IV (13): 177–180.

- Maryon, Herbert (10 May 1922a). "Design in Jewelry". The Jewelers' Circular. LXXXIV (15): 97.

- Republication of passages from Maryon 1912, pp. 280–281

- Maryon, Herbert (12 July 1922b). "A Critique on Cellini". The Jewelers' Circular. LXXXIV (24): 89.

- Republication of Maryon 1912, ch. XXXIII

- Cowen, J. D. & Maryon, Herbert (1935). "The Whittingham Sword". Archaeologia Aeliana. 4. XII: 280–309. ISSN 0261-3417.

- Maryon, Herbert (1935). "The "Casting-On" of a Sword Hilt in the Bronze Age". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle upon Tyne. 4. VI: 41–42.

- Maryon, Herbert (February 1936). "Granular Work of the Ancient Goldsmiths". Goldsmiths Journal: 554–556.

- Maryon, Herbert (April 1936). "Solders Used by the Ancient Goldsmiths". Goldsmiths Journal: 72–73.

- Maryon, Herbert (June 1936). "Jewellery of 5,000 Years Ago". Goldsmiths Journal: 344–345.

- Maryon, Herbert (1936). "Excavation of two Bronze Age barrows at Kirkhaugh, Northumberland". Archaeologia Aeliana. 4. XIII: 207–217. ISSN 0261-3417.

- Maryon, Herbert (October 1936). "Soldering and Welding in the Bronze and Early Iron Ages". Technical Studies in the Field of the Fine Arts. V (2): 75–108. ISSN 0096-9346.

- Maryon, Herbert (June 1937). "Prehistoric Soldering and Welding". Antiquity. XI (42): 208–209. doi:10.1017/S0003598X0011662X.

- Maryon, Herbert (September 1937). "A Passage on Sculpture by Diodorus of Sicily". Antiquity. XI (43): 344–348. doi:10.1017/S0003598X0011676X.

- Maryon, Herbert (April 1938). "The Technical Methods of the Irish Smiths in the Bronze and Early Iron Ages". Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, Section C. XLIV: 181–228. JSTOR 25516012.

- Maryon, Herbert (July 1938). "Some Prehistoric Metalworkers' Tools". The Antiquaries Journal. Society of Antiquaries of London. XVIII (3): 243–250. doi:10.1017/S0003581500007228.

- Maryon, Herbert (June 1939). "Ancient Hand-Anvil from Thomastown, Co. Kilkenny" (PDF). Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society. XLIV (159): 62–63. ISSN 0010-8731.

- Maryon, Herbert (1939). "The Gold Ornaments from Cooper's Hill, Alnwick". Archaeologia Aeliana. 4. XVI: 101–108. ISSN 0261-3417.

- Maryon, Herbert (November 1941). "Archæology and Metallurgy. I. Welding and Soldering". Man. XLI: 118–124. JSTOR 2791583.

- Maryon, Herbert (November 1941). "Archæology and Metallurgy: II. The Metallurgy of Gold and Platinum in Pre-Columbian Ecuador". Man. XLI: 124–126. JSTOR 2791584.

- Maryon, Herbert (July 1944). "The Bawsey Torc". The Antiquaries Journal. Society of Antiquaries of London. XXIV (3–4): 149–151. doi:10.1017/S0003581500095640.

- Maryon, Herbert (March 1946). "The Sutton Hoo Shield". Antiquity. XX (77): 21–30. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00019232.

- Maryon, Herbert (September 1947). "The Sutton Hoo Helmet". Antiquity. XXI (83): 137–144. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00016598.

- Maryon, Herbert (1948a). "A Sword of the Nydam Type from Ely Fields Farm, near Ely". Proceedings of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society. XLI: 73–76. doi:10.5284/1034398.

- Maryon, Herbert (March 1948b). "The Mildenhall Treasure, Some Technical Problems: Part I". Man. XLVIII: 25–27. JSTOR 2792450.

- Maryon, Herbert (April 1948c). "The Mildenhall Treasure, Some Technical Problems: Part II". Man. XLVIII: 38–41. JSTOR 2792704.

- Maryon, Herbert (April 1949). "Metal Working in the Ancient World". American Journal of Archaeology. LII (2): 93–125. JSTOR 500498.

- Maryon, Herbert (July 1950). "A Sword of the Viking Period from the River Witham". The Antiquaries Journal. Society of Antiquaries of London. XXX (3–4): 175–179. doi:10.1017/S0003581500087849.

- Maryon, Herbert (April 1951). "New Light on the Royal Gold Cup". The British Museum Quarterly. XVI (2): 56–58. doi:10.2307/4422320. JSTOR 4422320.

- Maryon, Herbert (June 1953). "The King John Cup at King's Lynn". The Connoisseur: 88–89. ISSN 0010-6275.

- Maryon, Herbert (1956). "The Colossus of Rhodes". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. LXXVI: 68–86. JSTOR 629554.

- Plenderleith, H. J. & Maryon, Herbert (January 1959). "The Royal Bronze Effigies in Westminster Abbey". The Antiquaries Journal. Society of Antiquaries of London. XXXIX (1–2): 87–90. doi:10.1017/S0003581500083633.

- Maryon, Herbert (February 1960a). "Pattern-Welding and Damascening of Sword-Blades—Part 1: Pattern-Welding". Studies in Conservation. 5 (1): 25–37. JSTOR 1505063.

- Maryon, Herbert (May 1960b). "Pattern-Welding and Damascening of Sword-Blades—Part 2: The Damascene Process". Studies in Conservation. 5 (2): 52–60. JSTOR 1504953.

- Maryon, Herbert (1961). "The Making of a Chinese Bronze Mirror". Archives of the Chinese Art Society of America. XV: 21–25. JSTOR 20067029.

- Maryon, Herbert; Organ, R. M.; Ellis, O. W.; Brick, R. M. & Sneyers, E. E. (April 1961). "Early Near Eastern Steel Swords". American Journal of Archaeology. 65 (2): 173–184. JSTOR 502669.

- Maryon, Herbert (1963). "The Making of a Chinese Bronze Mirror, Part 2". Archives of the Chinese Art Society of America. XVII: 23–25. JSTOR 20067056.

- Maryon, Herbert (1963). "A Note on Magic Mirrors". Archives of the Chinese Art Society of America. XVII: 26–28. JSTOR 20067057.

Other

- Maryon, Herbert (9 December 1933b). "Modern Sculpture". Points of View: Letters from Readers. The Scotsman (28, 248). Edinburgh. p. 15.

- Maryon, Herbert (December 1933c). "Modern Sculpture". The Bookman. LXXXV (507): 411.

- Maryon, Herbert (October 1934). "Modern Sculpture". The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs. LXV (CCCLXXIX): 189–190. JSTOR 865986.

Primary sources

- "Herbert James Maryon in the England & Wales, Civil Registration Birth Index, 1837-1915". Ancestry Library. 2006. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- "Herbert G Maryon in the 1891 England Census". Ancestry Library. 2005. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- "Herbert James Maryon in the 1901 England Census". Ancestry Library. 2005. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- "Herbert James Maryon in the England, Select Marriages, 1538–1973". Ancestry Library. 2014. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- "Herbert James Maryon in the England & Wales, Civil Registration Marriage Index, 1837-1915". Ancestry Library. 2006. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- "Herbert James Maryon in the 1911 England Census". Ancestry Library. 2011. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- "Herbert James Maryon in the England & Wales, Civil Registration Marriage Index, 1916-2005". Ancestry Library. 2010. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- "Herbert James Maryon in the England & Wales, National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills and Administrations), 1858-1966, 1973-1995". Ancestry Library. 2010. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- "H J Maryon in the Fremantle, Western Australia, Passenger Lists, 1897-1963". Ancestry Library. 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

Secondary sources

- Annual Report (PDF) (Report). Toronto: Royal Ontario Museum. 1953–54.

- "Art School Notes: Reading". The International Studio. New York: John Lane Co. XXXIV (136): 342. June 1908.

- Arwidsson, Greta (1942). Valsgärde 6. Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksells Boktryckeri A.B.

- B., L. B. (3 January 1934a). "Sculpture". Books of the Day. The Manchester Guardian (27, 243). Manchester. p. 5.

- B., R. P. (July 1934b). "Review of Modern Sculpture". The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs. LXV (CCCLXXVI): 50. JSTOR 865852.

- Biddle, Martin (3 December 2015). "Rupert Leo Scott Bruce-Mitford: 1914–1994" (PDF). Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the British Academy. British Academy. XIV: 58–86. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- "British Museum Expert Speaks Today, 5 P.M. on Ancient Swords" (PDF). The Tech. 82 (12). Cambridge, Massachusetts. 2 May 1962. p. 1.

- Bruce, Ian (2001). The Loving Eye and Skilful Hand: The Keswick School of Industrial Arts. Carlisle: Bookcase.

- Bruce-Mitford, Rupert (1947). The Sutton Hoo Ship-Burial: A Provisional Guide. London: Trustees of the British Museum.

- Bruce-Mitford, Rupert (1949). The Sutton Hoo Ship-Burial: Recent Theories and Some Comments on General Interpretation. Ipswich: Suffolk Institute of Archaeology.

- Bruce-Mitford, Rupert (23 July 1965). "Mr. Herbert Maryon". Obituary. The Times (56381). London. p. 14.

- Bruce-Mitford, Rupert (March 1968). "Sutton Hoo Excavations, 1965–7". Antiquity. XLII (165): 36–39. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00033810.

- Bruce-Mitford, Rupert (1970). Preface. The Treasure of Sutton Hoo: Ship-Burial for an Anglo-Saxon King. By Grohskopf, Bernice. New York: Atheneum. LCCN 74-86555.

- Bruce-Mitford, Rupert (Autumn 1972). "The Sutton Hoo Helmet: A New Reconstruction". The British Museum Quarterly. British Museum. XXXVI (3–4): 120–130. JSTOR 4423116.

- Bruce-Mitford, Rupert (1974a). Aspects of Anglo-Saxon Archaeology: Sutton Hoo and Other Discoveries. London: Victor Gollancz. ISBN 0-575-01704-X.

- Bruce-Mitford, Rupert (1974b). "Exhibits at Ballots: 5. A replica of the Sutton Hoo helmet made in the Tower Armouries, 1973". The Antiquaries Journal. Society of Antiquaries of London. LIV (2): 285–286. doi:10.1017/S0003581500042529.

- Bruce-Mitford, Rupert (1975). The Sutton Hoo Ship-Burial, Volume 1: Excavations, Background, the Ship, Dating and Inventory. London: British Museum Publications. ISBN 0-7141-1334-4.

- Bruce-Mitford, Rupert (1978). The Sutton Hoo Ship-Burial, Volume 2: Arms, Armour and Regalia. London: British Museum Publications. ISBN 9780714113319.

- Bruce-Mitford, Rupert (1983a). The Sutton Hoo Ship-Burial, Volume 3: Late Roman and Byzantine silver, hanging-bowls, drinking vessels, cauldrons and other containers, textiles, the lyre, pottery bottle and other items. I. London: British Museum Publications. ISBN 0-7141-0529-5.

- Bruce-Mitford, Rupert (1983b). The Sutton Hoo Ship-Burial, Volume 3: Late Roman and Byzantine silver, hanging-bowls, drinking vessels, cauldrons and other containers, textiles, the lyre, pottery bottle and other items. II. London: British Museum Publications. ISBN 0-7141-0530-9.

- Bruce-Mitford, Rupert (1989a). "Early Thoughts on Sutton Hoo" (PDF). Saxon (10).

- Bruce-Mitford, Rupert (1989b). Anglo-Saxon and Mediaeval Archaeology, History and Art, with special reference to Sutton Hoo: The highly important Working Library and Archive of more than 6,000 titles formed by Dr. Rupert L.S. Bruce-Mitford FBA, D.Litt., FSA. Wickmere: Merrion Book Co.

- "By Balloon to Parnassus". The New Statesman and Nation. New Series. VI (148): 848. 23 December 1933.

- Caple, Chris (2000). "Restoration: 9A Case study: Sutton Hoo Helmet". Conservation Skills: Judgement, Method and Decision Making. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-18880-6.

- Catalogue of the Sixth Exhibition. London: Arts & Crafts Exhibition Society. 1899.

- "Contributors to this Issue: Herbert Maryon". Studies in Conservation. 5 (1). February 1960. doi:10.2307/1505065. JSTOR 1505065.

- "Contributors to this Issue: Herbert Maryon". Studies in Conservation. 5 (2). May 1960. doi:10.2307/1504958. JSTOR 1504958.

- Crouch, Philip & Barnes, Jamie. "A Brief History of the Keswick School of Industrial Art" (PDF). Allerdale Borough Council. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- "Current Literature: Modern Sculpture". The Spectator. 152 (5, 506): 30. 5 January 1934.

- de Callataÿ, Godefroid (2006). "The Colossus of Rhodes: Ancient Texts and Modern Representations". In Ligota, Christopher R. & Quantin, Jean-Louis. History of Scholarship: A Selection of Papers from the Seminar on the History of Scholarship Held Annually at the Warburg Institute. London: Oxford University Press. pp. 39–73. ISBN 0-19-928431-8.

- Dickie, Matthew Wallace (1996). "What is a Kolossos and how were Kolossoi Made in the Hellenistic Period?". Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies. Duke University Press. 37 (3): 237–257.

- Easby, Jr., Dudley T. (July 1966). "Necrology". American Journal of Archaeology. Archaeological Institute of America. 70 (3): 287. JSTOR 501899.

- "East Knoyle War Memorial". The Western Gazette (9557). Yeovil. 1 October 1920. p. 8.

- "East Knoyle War Memorial". Historic England. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- Ferrari, Dino (6 May 1934). "Some of the Sculpture of Our Day". Book Review. The New York Times. LXXXIII (27, 861). New York City. p. 5-21.

- Green, Charles (1963). Sutton Hoo: The Excavation of a Royal Ship-Burial. New York: Barnes & Novle.

- Grigson, Geoffrey (December 1933). "Review of Modern Sculpture, and Modelling and Sculpture in the Making". The Bookman. LXXXV (507): 213–214.

- Grohskopf, Bernice (1970). The Treasure of Sutton Hoo: Ship-Burial for an Anglo-Saxon King. New York: Atheneum. LCCN 74-86555.

- H., C. (October 1899). "Studio Talk: London". The International Studio. New York: John Lane Co. VIII (32): 266–271.

- Haynes, D. E. L. (1957). "Philo of Byzantium and the Colossus of Rhodes". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. LXXVII (2): 311–312. doi:10.2307/629373. JSTOR 629373.

- "Herbert James Maryon". Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain and Ireland 1851–1951. University of Glasgow History of Art. 2011a. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- "Herbert James Maryon". Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain and Ireland 1851–1951. University of Glasgow History of Art. 2011b. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- "Herbert Maryon". Deaths. The Ottawa Journal. Ottawa, Ontario. Canadian Press. 21 July 1965. p. 34. Retrieved 13 November 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Herbert Maryon". Obituaries. The Brandon Sun. Brandon, Manitoba. Canadian Press. 23 July 1965. p. 11. Retrieved 13 November 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- Huey, Arthur D. (22 March 1962a). "Mirrors Fail to Reflect Enthusiasm". The Kansas City Times. Kansas City, Missouri. p. 1. Retrieved 17 October 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- Huey, Arthur D. (22 March 1962b). "Mirrors Fail to Reflect Enthusiasm". The Kansas City Times. Kansas City, Missouri. p. 2. Retrieved 17 October 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- The Institution of Mechanical Engineers (1918). "Herbert James Maryon, in To be considered by the Applications Committee on Wednesday, 24th April, and by the Council on Friday, 3rd May 1918.". Proposals for Membership, Etc. London. pp. 337–339. Retrieved 23 October 2016 – via Ancestry.com. (Subscription required (help)).

- The Institution of Mechanical Engineers (June 1931). "Unveiling of Replica of Tablet Affixed to George Stephenson's Cottage at Wylam-on-Tyne". Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers. 120: iv, 249–251. doi:10.1243/PIME_PROC_1931_120_012_02.

- "Inventor of Turbine: Memorial to Sir Charles Parsons Unveiled". The Gazette (51). Montreal. 1 March 1933. p. CLXII.

- Knutsen, Willie & Knutsen, Will C. (2005). Arctic Sun on My Path: The True Story of America's Last Great Polar Explorer. Explorers Club Books. Guilford, Connecticut: The Lyons Press. ISBN 978-1-59228-672-0.

- Lindqvist, Sune (September 1948). Translated by Bruce-Mitford, Rupert. "Sutton Hoo and Beowulf". Antiquity. XXII (87): 131–140. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00019669.

- "A Magnificent Silver and Iron Helmet — A Portrait of a Syrian Royal General About the Time of the Crucifixion: Newly Restored and Now Exhibited on Loan at the British Museum". Illustrated London News (6, 054). 27 August 1955. p. 769.

- "Margaret Joan Sawatsky". Winnipeg Free Press Passages. 8 October 2005. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- "Marriage: Mr. J. G. Darley and Miss Maryon". The Times (45250). London. 9 July 1929. p. 19.

- "Marriages at St Michael and All Angels in the Parish of Hawkshead: Marriages recorded in the Register for 1924 – 1933". Lancashire OnLine Parish Clerks. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- Marriott, Charles (18 January 1934). "Books on Sculpture". Literary Supplement. The Times (1668). London. p. 43.

- "Herbert Maryon". Obituary. The Daily Telegraph. London. 16 July 1965. p. 18. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- "Maryon". Deaths. The Daily Telegraph. London. 16 July 1965. p. 32. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- "MARYON, Herbert". Who Was Who. Oxford University Press. April 2014. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- Maryon, John Ernest (1895). Records and Pedigree of the Family of Maryon of Essex and Herts. London: Self-published. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- Marzinzik, Sonja (2007). The Sutton Hoo Helmet. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-2325-7.

- "Metalwork and Enamelling". Dover Publications. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- "Modern Sculpture". Art Interests. The Scotsman (28, 232). Edinburgh. 21 November 1933. p. 11.

- "The Monuments Men: Maj. Denys Eyre Lankester Haynes (1913-1994)". Monuments Men Foundation. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- "Mortimer War Memorial". War Memorials Register. Imperial War Museums. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- "Principal Librarians and Directors of the British Museum". The British Museum. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- "Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries". The Antiquaries Journal. Society of Antiquaries of London. XXIX (1–2): 135. January 1949. doi:10.1017/S000358150002103X.

- "Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries". The Antiquaries Journal. Society of Antiquaries of London. XXIX (3–4): 242. July 1949. doi:10.1017/S0003581500017480.

- "Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries". The Antiquaries Journal. Society of Antiquaries of London. XXXIV (1–2): 144. 1954. doi:10.1017/S0003581500073686.

- "Reading University". War Memorials Register. Imperial War Museums. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- "Review of Modern Sculpture". The Connoisseur. 94: 124. January 1934. ISSN 0010-6275.

- ""Rocket" Centenary: Tablet on George Stephenson's House". Lake Wakatip Mail (3, 909). Queenstown, New Zealand. 6 August 1929. p. 7.

- "Rupert Bruce-Mitford". Obituaries. The Times (64909). London. 23 March 1994. p. 21. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- Seyrig, Henri (June 1952). "A Helmet from Emisa". Archaeology. Archaeological Institute of America. 5 (2): 66–69. JSTOR 41663047.

- Sorensen, Lee. "Kendrick, T. D." Dictionary of Art Historians. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- Schweppe, Sylvia (29 July 1965a). "Mr. Herbert Maryon". Obituary. The Times (56386). London. p. 12. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- Schweppe, Sylvia (November 1965b). "Herbert Maryon: Fellow of I.I.C.". Studies in Conservation. International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works. 10 (4): 176. doi:10.1179/sic.1965.022. ISSN 0039-3630. JSTOR 1505372.

- "Sir Charles Parsons Memorial Plaque". Friends of Discovery Museum. 30 October 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- "Sir Charles Parsons: Memorial Unveiled at Wallsend". Home News. The Times (46308). London. 5 December 1932. pp. 9, 16. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- "Sir Thomas Kendrick: Keeper of British Museum". Obituaries Supplement. The Times (60482). London. 23 November 1979. p. VII. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- "Smaller Gulps". The Times Diary. The Times (58723). London. 5 March 1973. p. 12. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- "Statue Tarred and Feathered: Outrage in Full View of Crowds". The Manchester Guardian (25, 945). Manchester. 26 October 1929. p. 13.

- "Supplement". The London Gazette (40787). 25 May 1956. pp. 3099–3138. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- "Sutton Hoo in 1951". Blogspot. 20 September 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- "The Sutton Hoo Shield". The Financial Times (25402). London. 12 March 1971. p. 3. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- "Sutton Hoo Treasures". News in Brief. The Times (50365). London. 1 February 1979. p. 6. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- "Tarred Statue of Industry: Sculptor's Defence of his Work". The Manchester Guardian (25, 947). Manchester. 29 October 1929. p. 3.

- "The Treasure of Sutton Hoo: King's Tomb is Greatest Find in Archaeology of England". Life. Vol. 31 no. 3. New York. 16 July 1951. pp. 82–85. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- "University of Reading War Memorial". Historic England. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- Williams, Dyfri (5 October 1994). "Obituary: D. E. L. Haynes". The Independent. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- Williams, Nigel (1992). "The Sutton Hoo Helmet". In Oddy, William Andrew. The Art of the Conservator. London: British Museum Press. pp. 73–88. ISBN 9780714120560.

- Wilson, David. M. (1960). Daniel, Glyn, ed. The Anglo-Saxons. Ancient Peoples and Places. 16. New York: Frederick A. Praeger. LCCN 60-8369.

- van Geersdaele, Peter C. (November 1969). "Moulding the Impression of the Sutton Hoo Ship". Studies in Conservation. 14 (4): 177–182. doi:10.2307/1505343. JSTOR 1505343.

- van Geersdaele, Peter C. (August 1970). "Making the Fibre Glass Replica of the Sutton Hoo Ship Impression". Studies in Conservation. 15 (3): 215–220. doi:10.2307/1505584. JSTOR 1505584.

Colossus articles

- "The Colossus Now Gets Debunked". The Austin Statesman. Austin, Texas. 4 December 1953. p. 20. Retrieved 18 October 2016 – via ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- "Ancient Wonder Called Sham: Colossus of Rhodes Is Debunked By Archaeologist". The Battle Creek Enquirer and News. Battle Creek, Michigan. 4 December 1953. p. 1. Retrieved 26 October 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Colossus of Rhodes: Scientist Says Wonder of World Statue Hollow Sham". The Corpus Christi Caller Times. Corpus Christi, Texas. 4 December 1953. p. 31. Retrieved 19 October 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Claims Famed Colossus Was Only Hollow Sham". Des Moines Tribune. Des Moines, Iowa. 4 December 1953. p. 11. Retrieved 26 October 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Colossus of Rhodes Is Described As Hollow Sham". The Fresno Bee. Fresno, California. 4 December 1953. p. 15. Retrieved 18 October 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Sculptor Explodes Myth Of Statue Astride Harbor". Lubbock Evening Journal. Lubbock, Texas. 4 December 1953. p. 10. Retrieved 21 October 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Archaeologist Says One Of 7 Wonders Of World A Sham". Macon Chronicle Herald. Macon, Missouri. 4 December 1953. p. 1. Retrieved 21 October 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Researcher Brands Colossus of Rhodes Nothing But Sham". The Mason City Globe-Gazette. Mason City, Iowa. 4 December 1953. p. 21. Retrieved 21 October 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Colossus of Rhodes a Hollow Sham, British Scientist Says". Moberly Monitor-Index. Moberly, Missouri. 4 December 1953. p. 1. Retrieved 18 October 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Colossus Called A Hollow Sham: Rhodes' World Wonder Didn't Straddle Old Port, Says Briton". The News Journal. Wilmington, Delaware. 4 December 1953. p. 24. Retrieved 24 October 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Colossus Of Rhodes, One Of 7 Wonders, Said Sham". The News Leader. Staunton, Virginia. 4 December 1953. p. 1. Retrieved 24 October 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "A Fraud, He Said". Oakland Tribune. Oakland, California. 4 December 1953. p. 2. Retrieved 26 October 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Colossus Is Termed 'Sham'". The Plain Speaker. Hazleton, Pennsylvania. 4 December 1953. p. 29. Retrieved 18 October 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Rhodes Colossus Didn't Span Port, Briton Declares". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. 4 December 1953. p. 5C. Retrieved 25 October 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Rhodes Colossus Is Labelled Sham". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Spokane, Washington. 4 December 1953. p. 12. Retrieved 18 October 2016 – via Google News Archive Search.

- "Colossus Called Sham". Tucson Daily Citizen. Tucson, Arizona. 4 December 1953. p. 2. Retrieved 18 October 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "One of World's 7 Wonders Described as Hollow Sham". The Vernon Daily Record. Vernon, Texas. 4 December 1953. p. 9. Retrieved 21 October 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Colossus of Rhodes Hollow Sham, Scientist Declares". Abilene Reporter-News. Abilene, Texas. 5 December 1953. p. 30. Retrieved 18 October 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Expert Debunks One of World Wonders: Colossus of Rhodes". Chicago Tribune. Chicago, Illinois. 5 December 1953. p. 4. Retrieved 24 October 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Scientist Describes Colossus Of Rhodes as 'Hollow Sham'". Council Bluffs Nonpareil. Council Bluffs, Iowa. 5 December 1953. p. 4. Retrieved 18 October 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "'Colossus' Is 'Sham:' Scientist". The Daily Times. Davenport, Iowa. 5 December 1953. p. 2B. Retrieved 26 October 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Hollow Sham?". The Detroit Free Press. Detroit, Michigan. 5 December 1953. p. 7. Retrieved 26 October 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Britisher Belittles World Mark". The Indiana Gazette. Indiana, Pennsylvania. 5 December 1953. p. 5. Retrieved 21 October 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Britisher Belittles World Mark". The Indiana Gazette. Indiana, Pennsylvania. 5 December 1953. p. 21. Retrieved 18 October 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Colossal Phony?". Minneapolis Tribune. Minneapolis, Minnesota. 5 December 1953. p. 12. Retrieved 26 October 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Colossus Of Rhodes 'Sham'". Petaluma Argus-Courier. Petaluma, California. 5 December 1953. p. 6. Retrieved 24 October 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Colossus of Rhodes Hollow Sham, British Scientist Says". The San Bernardino County Sun. San Bernardino, California. 5 December 1953. p. 21. Retrieved 18 October 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Colossus Only Small Giant, Briton Holds". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. 5 December 1953. p. 4. Retrieved 19 October 2016 – via ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- "Debunking Old Beliefs Doesn't Hurt The Colossus". The Battle Creek Enquirer and News. Battle Creek, Michigan. 6 December 1953. p. 6. Retrieved 26 October 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Scientist Describes Colossus Of Rhodes as 'Hollow Sham'". Council Bluffs Nonpareil. Council Bluffs, Iowa. 6 December 1953. p. 47. Retrieved 18 October 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "British Scientist States Colossus Is Hollow Sham". The Odessa American. Odessa, Texas. 6 December 1953. p. 3. Retrieved 26 October 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Says Colossus Of Rhodes Was Sham". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Santa Cruz, California. 6 December 1953. p. 21. Retrieved 18 October 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Describe Colossus Of Rhodes as Sham". The Sedalia Democrat. Sedalia, Missouri. 6 December 1953. p. 29. Retrieved 21 October 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Collossus [sic] of Rhodes Described as Hollow Sham by Scientist". The Progress-Index. Petersburg, Virginia. 7 December 1953. p. 12. Retrieved 19 October 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Describes One of Seven Wonders Of World As Being Just A Hollow Sham". The Eagle. Bryan, Texas. 8 December 1953. p. 10. Retrieved 18 October 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Oh, The Shame of This Sham". The Indianapolis News. Indianapolis, Indiana. 8 December 1953. p. 3. Retrieved 24 October 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Ancient World Wonder Called Hollow Sham". Reno Gazette. Reno, Nevada. 8 December 1953. p. 7. Retrieved 26 October 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Full Circle". The Nashville Tennessean. Nashville, Tennessee. 8 December 1953. p. 20. Retrieved 26 October 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Only 6 1/2 World Wonders?". The Kansas City Times. Kansas City, Missouri. 12 December 1953. p. 34. Retrieved 18 October 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- Parker, T. H. (13 December 1953). "The Lively Arts: The Mighty and the Fallen". The Hartford Courant. Hartford, Connecticut. p. IV (2). Retrieved 26 October 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Spare Us Something". The Indianapolis News. Indianapolis, Indiana. 15 December 1953. p. 10. Retrieved 26 October 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Spare Us Something". Muncie Evening Press. Muncie, Indiana. 16 December 1953. p. 4. Retrieved 26 October 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Fraudulent Colossos [sic]". Corsicana Daily Sun. Corsicana, Texas. 21 December 1953. p. 2 (8). Retrieved 26 October 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Guest Editorial: Losing the Seventh Wonder". The Hammond Times. Hammond, Indiana. 14 January 1954. p. 6. Retrieved 26 October 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Only 6 1/2 Wonders?". Tucson Daily Citizen. Tucson, Arizona. 4 February 1954. p. 12. Retrieved 18 October 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- Wade, William (20 January 1954). "Folklore". Anderson Herald. Anderson, Indiana. p. 4. Retrieved 21 October 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Ancient 'Wonder' Doubted". Alton Evening Telegraph. Alton, Illinois. 25 March 1954. p. 9. Retrieved 21 October 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Ancient 'Wonder' Doubted". The Grape Belt and Chautauqua Farmer. Dunkirk, New York. 2 April 1954. p. 18. Retrieved 18 October 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Old 'Wonder' Doubted". Greeley Daily Tribune. Greeley, Colorado. 1 May 1954. p. 7. Retrieved 18 October 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Ancient "Wonder" Doubted". Wausau Daily Record-Herald. Wasau, Wisconsin. 21 June 1954. p. 16. Retrieved 26 October 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- Scarre, Chris (31 August 1991). "From Rhodes to Ruins". Saturday Review. The Times (64113). London. p. 14[S]. Retrieved 25 November 2016.