Hemp paper

Hemp paper means paper varieties consisting exclusively or to a large extent from pulp obtained from fibers of industrial hemp. The products are mainly specialty papers such as cigarette paper, banknotes and technical filter papers. Compared to wood pulp, hemp pulp offers a four to five times longer fibre, a significantly lower lignin fraction as well as a higher tear resistance and tensile strength. However, production costs are about four times higher than for paper from wood, so hemp paper could not be used for mass applications as printing, writing and packaging paper.

History

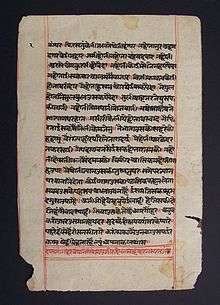

The first identified coarse paper, made from hemp, dates to the early Western Han Dynasty, 200 years before the nominal invention of papermaking by Cai Lun, who improved and standardized paper production using a range of inexpensive materials, including hemp ends, around 2000 years ago.[1] Recycled hemp clothing, rags, and fishing nets were used as inputs for paper production.[2] By the sixth century AD, the papermaking process spread to Korea, where cannabis had been used previously for thousands of years, and Japan, where cannabis had been used for 10,000 years.[3]

Early Western use

Hemp paper only reached Europe in the 13th century via the Middle East. In Germany it has been proven for the first time in the 14th century. It was not until the 19th century that methods were established for the production of paper from wood pulp, which were cheaper than the hemp paper production and, above all, repressed in the area of writing and printing papers. Notably, the first copies of the Bible were made of hemp paper.

The Saint Petersburg, Russia, paper mill of Goznak opened in 1818. It used hemp as its main input material. Paper from the mill was used in the printing of "bank notes, stamped paper, credit bills, postal stamps, bonds, stocks, and other watermarked paper."[4]

20th century

In 1916, U.S. Department of Agriculture chief scientists Lyster Hoxie Dewey and Jason L. Merrill created paper made from hemp pulp and concluded that paper from hemp hurds was "favorable in comparison with those used with pulp wood."[5][6] The chemical composition of hemp hurds is similar to that of wood,[7] making hemp a good choice as a raw material for manufacturing paper. Modern research has not confirmed the positive finding about hemp hurds from 1916. A later book about hemp and other fibers by the same L.H. Dewey(1943) have no words about hemp as a raw material for production of paper.[8][9] Dried hemp has about 57% cellulose (the principal ingredient in paper), compared to about 40-50% in wood.[10][11][12] Hemp also has the advantage of a lower lignin content: hemp contains only 5-24% lignin[13] against the 20-35% found in wood.[14] This lignin must be removed chemically and wood requires more use of chemicals in the process.[15] The actual production of hemp fiber in the U.S continued to decline until 1933 to around 500 tons/year. Between 1934 and 1935, the cultivation of hemp began to increase, but still at a very low level and with no significant increase of paper from hemp.[16][17]

After the Second World War, industrial hemp was only grown on micro-plots. Although the industrial hemp bred in the 1950s and 1960s is harmless because of the almost complete absence of THC, cultivation has been banned in many countries in recent decades. In Germany, growing hemp was completely prohibited between 1982 and 1995 by the Betäubungsmittelgesetz (Narcotics Act, the national controlled-substances law) in order to prevent the illegal use of cannabis as a narcotic. Especially in France, the varieties of hemp used for the manufacture of cigarette paper were still in use and grown.

Fiber sources

Before the industrialisation of paper production the most common fibre source was recycled fibres from used textiles, called rags. The rags were from hemp, linen and cotton.[18] A process for removing printing inks from recycled paper was invented by German jurist Justus Claproth in 1774.[18] Today this method is called deinking. It was not until the introduction of wood pulp in 1843 that paper production was not dependent on recycled materials from ragpickers.[18]

Contemporary

Currently there is a small niche market for hemp pulp, for example as cigarette paper.[19] Hemp fiber is mixed with fiber from other sources than hemp. In 1994 there was no significant production of 100% true hemp paper.[20] World hemp pulp production was believed to be around 120,000 tons per year in 1991 which was about 0.05% of the world's annual pulp production volume.[21] The total world production of hemp fiber had in 2003 declined to about 60,000 from 80,000 tons.[19] This can be compared to a typical pulp mill for wood fiber, which is never smaller than 250,000 tons per annum.[20][22] The cost of hemp pulp is approximately six times that of wood pulp,[21] mostly because of the small size and outdated equipment of the few hemp processing plants in the Western world, and because hemp is harvested once a year (during August) and needs to be stored to feed the mill the whole year through. This storage requires a lot of (mostly manual) handling of the bulky stalk bundles. Another issue is that the entire hemp plant cannot be economically prepared for paper production. While the wood products industry uses nearly 100% of the fiber from harvested trees, only about 25% of the dried hemp stem—the bark, called bast—contains the long, strong fibers desirable for paper production.[23] All this accounts for a high raw material cost. Hemp pulp is bleached with hydrogen peroxide, a process today also commonly used for wood pulp.

Market share

Around the year 2000, the production quantity of flax and hemp pulp total 25000-30000 tons per year, having been produced from approximately 37000-45000 tonnes fibers. Up to 80% of the produced pulp is used for specialty papers (including 95% of cigarette paper). Only about 20% hemp fiber input goes into the standard pulp area and are here mostly in lower quality (untreated oakum high shive content added) wood pulps. With hemp pulp alone, the proportion of specialty papers probably at about 99%. The market is considered saturated with little or no growth in this area.[24][25]

The use of hemp fiber for paper production represented 90% of the (legal) use of hemp in Europe at the end of the 1990s, with the release of the cultivation of industrial hemp in other parts of Europe in recent years, the share of the increase in other types of use (textiles, natural fiber reinforced plastics) is currently around 70 to 80% and is still the most important hemp product line in Europe. Today, hemp is used for cigarette paper among other things in Spain and in United Kingdom.[26]

Around the year 2000, the production volume for flax and hemp pulp totaled 25,000 to 30,000 tonnes per year, which was produced from about 37,000 to 45,000 tonnes of fibers. Up to 80% of the pulp produced in this way is used for special papers (including 95% cigarette paper), only about 20% go into the standard pulp area and are here in mostly lower quality (unpurified tow with high hurd content) wood pulp. In the case of hemp pulp alone, the proportion of specialty papers is probably around 99%. The market is considered to be saturated, so no or only low growth in this area is to be expected.[27]

See also

- Banana paper

- India paper, incorporates hemp, used for printing Bibles

References

- ↑ "Cai Lun Improved the Papermaking Technology". chinaculture.org.

- ↑ Clarke p. 188

- ↑ Clarke p. 187

- ↑ A brief history of the St. Petersburg Paper Mill of Goznak (www.goznak.spb.ru) Archived May 28, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Dewey and Merrill, U.S.D.A. Bulletin No. 404, Hemp Hurds as Paper-Making Material, Washington, D.C., October 14, 1916. Page 25

- ↑ "The Project Gutenberg eBook of Hemp Hurds as Paper-Making Material, by Lyster H. Dewey and Jason L. Merrill". Gutenberg.org. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- ↑ Stevulova, Nadezda (December 2014). "Properties Characterization of Chemically Modified Hemp Hurds". Materials. 7: 8131–8150. doi:10.3390/ma7128131.

- ↑ Dewey LH (1943). "Fiber production in the western hemisphere". United States Printing Office, Washington. p. 67. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ↑ French, Laurence; Manzanárez, Magdaleno (2004). NAFTA & neocolonialism: comparative criminal, human & social justice. University Press of America. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-7618-2890-7.

- ↑ Cellulose. (2008). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved January 11, 2008, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ↑ Chemical Composition of Wood. ipst.gatech.edu.

- ↑ Piotrowski, Stephan and Carus, Michael (May 2011) Multi-criteria evaluation of lignocellulosic niche crops for use in biorefinery processes. nova-Institut GmbH, Hürth, Germany.

- ↑ Multi-criteria evaluation of lignocellulosic niche crops for use in biorefinery processes. nova-Institut GmbH, Hürth, Germany.

- ↑ Li Jingjing (2011) Isolation of Lignin from Wood. SAIMAA UNIVERSITY OF APPLIED SCIENCES.

- ↑ "Papper". Hampa.net. Retrieved 2013-11-09.

- ↑ "David P. West: Fiber Wars: The Extinction of Kentucky Hemp". Gametec.com. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- ↑ "Additional Statement of H.J. Anslinger, Commissioner of Narcotics". Retrieved 2006-03-25.

- 1 2 3 Göttsching, Lothar; Pakarinen, Heikki (2000), "1", Recycled Fiber and Deinking, Papermaking Science and Technology, 7, Finland: Fapet Oy, pp. 12–14, ISBN 952-5216-07-1

- 1 2 "Michael Karus:European hemp industry 2001 till 2004: Cultivation, raw materials, products and trends, 2005" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- 1 2 "Steam energy:Hemp Pulp & Paper Production, January 1st 1994". Hempline.com. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- 1 2 Van Roekel; Gerjan J. (1994). "Hemp Pulp and Paper Production". Journal of the International Hemp Association. Wageningen, The Netherlands.

- ↑ "Anatomy of a Modern Paper Mill, Faculty of Natural Resources Management, Lakehead University". Borealforest.org. Retrieved 2013-11-09.

- ↑ "Boise: Nonwood Alternatives to Wood Fiber in Paper". bc.com. 2007-07-08. Archived from the original on July 8, 2007. Retrieved 2013-11-09.

- ↑ Ivan Bócsa, Michael Karus, Daike Lohmeyer: The cultivation of hemp. Botany, varieties, cultivation and harvesting, markets and product lines. 2 support, agricultural Verlag GmbH, Münster 2000th

- ↑ Michael Carus et al. Study of market and competition for natural fibers and natural fiber materials (Germany and EU) trade talks Gülzower 26, ed. of the Agency of Renewable Resources, Gülzow 2008 Download nova-Institut (ed.): The small hemp-Lexikon Verlag The Workshop, Göttingen, 2. Edition, 2003, page 79 ISBN 3-89533-271-2

- ↑ Carus et al. (2008)

- ↑ Carus et al. (2008)

Sources

- Ivan Bócsa, Michael Karus, Daike Lohmeyer (2000), Der Hanfanbau. Botanik, Sorten, Anbau und Ernte, Märkte und Produktlinien [The growing of hemp. Botany, varieties, cultivation and harvesting, markets and product lines] (2nd ed.), Münster: Agricultural Verlag GmbH

- Michael Carus et al. (2008), Studie zur Markt- und Konkurrenzsituation bei Naturfasern und Naturfaser-Werkstoffen (Deutschland und EU) [Study of the market and competitive situation of natural fibers and natural fiber materials (Germany and EU)] (PDF), Gülzow: Gülzower Fachgespräche 26, eds. By the specialist agency renewable raw Materials e.v.,

- Clarke, Robert; Merlin, Mark (1 September 2013), Cannabis: Evolution and Ethnobotany, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-95457-1, OCLC 92796711

- Nova-Institut (eds.) (2003), Das kleine Hanf-Lexikon [The small hemp lexicon] (2nd ed.), Göttingen: Verlag Die Werkstatt, p. 79, ISBN 3-89533-271-2

- Jürgen Karmann (2015), Hanfpapier [Hemp Paper], Mönchengladbach: Tribal Paper