Health in Ghana

| |

|---|---|

| Health indicators | |

| Life expectancy | 66 |

| Infant mortality | 39 |

| Fertility | 2.12 |

| Sanitation | 14% (2010) |

| Smoker | 1% |

| Obesity female | 7% |

| Obesity male | 2% |

| Malnutrition | 1% |

| HIV | 0.7% |

Health in Ghana includes the healthcare systems on prevention, care and treatment of diseases and other maladies.

History

The history of health in Ghana was heavily influenced by international actors such as Christian missionaries, European colonists, the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund.[1] In addition, the democratic shift in Ghana spurred healthcare reforms in an attempt to address the presence of infectious and noncommunicable diseases eventually resulting in the formation of the National Health insurance Scheme in place today.[2][3]

The Precolonial Period

In precolonial Ghana, infectious diseases were the main cause of morbidity and mortality.[2] Traditional village priests, clerics, and herbalists were the primary care givers, offering advice and treatment to the sick.[4] Premodern traditional beliefs stressed the combination of spiritual and physical healing with priests and clerics identifying the supernatural causes of disease and its remedies and herbalists offering medicinal herbs. The intersection of spirituality and medicine can be seen in priests using practices such as divination to determine the cause of illness and suggesting curative sacrifices before prescribing medicinal herbs obtained from herbalists.[4]

The Colonial Period

In 1874 Ghana was officially proclaimed a British colony. Ghana proved to be an extremely dangerous disease environment for European colonists driving the British Colonial Administration to establish a Medical Department bringing about an introduction to a formal medical system, consisting of a Laboratory Branch for research, a Medical Branch of hospitals and clinics, and the Sanitary Branch for public health centered near British posts and towns.[1] In addition to hospitals and clinics staffed with British medical professionals, these select towns were also provided anti-malaria medication to be distributed to colonists and to sell to local Ghanaians.[1] in 1878, the Towns, Police, and Public Health Ordinance was enforced, initiating the construction and demolishing of infrastructure, draining of the streets, and issuing of fines to those that failed to comply with the heads of the colony. In 1893, a Public Works Department was introduced to implement a working sanitation system in urban colonial centers.[4]

After the World War II it became increasingly clear that with improved transportation worldwide, international health policy needed to be strengthened.[1] Organizations such as the World Health Organization and the United Nations Children's Fund were active in providing money and support to provide additional western medical care in Ghana.[1][5] These organizations provided, "financial and technical assistance for the elimination of diseases and the improvement of health standards."[4] Traditional health practices were not recognized by these initiatives or the British Medical Department in urban areas and were shunned by Christian missionaries in rural areas. However, traditional priests, clerics, and herbalists still remained important health providers especially in rural areas where health centers were scarce.[5]

The Nationalist Period

Ghana gained its independence in 1957 and in held its first multiparty elections as a republic in 1960 electing Kwame Nkrumah as Ghana’s first President as part of the Convention People's Party.[3] While in office, Nkrumah pushed health and education policies that aimed to make these services more available and accessible; however, these policies were still mainly targeted at urban populations with 76% of doctors practicing in urban areas while only 23% of the population lived there.[1] During the nationalist period we see a shift in disease rates where the main causes of morbidity and mortality among wealthy communities are now chronic diseases due to their increased access to improving healthcare.[2] In addition, Nkrumah focused on curative healthcare and a public health approach that focused mainly on the control of outbreaks and epidemics.[2] These health programs were financed entirely through general taxation but with free public healthcare and large government spending, Ghana found itself struggling economically. Not long after Nkrumah left office in 1966, subsequent governments decided to continue to keep out of pocket fees low in addition to cutting government healthcare spending with the 1969 Hospital Fees Decree and the 1970 Hospitals Fees Act in the hopes of recovering fees and bolstering the economy.[3] Even with the cut in government spending, economic conditions continued to worsen as did healthcare services. By the 1980s, many social services, including healthcare, were inadequate and could not provide sufficient care and drugs despite the fact that healthcare was virtually free.[3]

The Rawlings Regime

On December 31, 1981, Jerry Rawlings overthrew the Limann government and became the Head of state of Ghana. With the World Bank and International Monetary Fund pressing the government to cut public spending through structural adjustment programs, the new regime passed the Hospital Fees Regulation in 1985 which resulted in greater out of pocket fees with the aim to be able to finance the drugs and resources the healthcare system needed.[2][3] This became the “cash and carry” system which required Ghanaians to pay out of pocket fees at each point of service. According to a number of empirical studies, this excluded many individuals from public healthcare who could not afford to pay these fees resulting in many Ghanaians belonging to the lower and middle classes to be dissatisfied with the cash-and-carry system; however, despite public disapproval in regards to healthcare, these structural adjustment programs are credited with saving Ghana's economy.[2]

The Fourth Republic

In the early 1990s, a democratic movement resurfaced and began to sweep through Africa. In response to democratic demands, the Rawlings regime transitioned to create a political party, the National Democratic Congress (NDC), legalized political parties, and organized Presidential and Parliamentary elections in 1992 during which Rawlings won with 58.3 percent of the vote.[3] The new democratic constitution under Rawlings included provisions to better social policies such as education and healthcare in the midst of the rising HIV/AIDS epidemic.[2] In 1996, a Medium Term Health Strategy was adopted that signified a shift from time-restricted, rigid projects to a more holistic approach that would better help develop the public health sector.[3] In 1997, a Health Fund was launched to provide a pool of funding for the sector.[3] Still, however, the biggest barrier to Ghanaians receiving proper healthcare was the high out of pocket fees. Despite exemptions expansions and infrastructure that increased access to healthcare, out of pocket fees remained a huge barrier.[3] In the election of 2000, John Kufuor as part of the New Patriotic Party (NPP) won over the NDC candidate and in 2003 he launched the National Health Insurance Scheme as under the National Health Insurance Act, providing universal healthcare to all Ghanaians.[3]

Healthcare

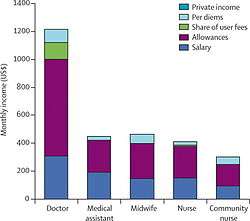

In Ghana, most health care is provided by the government and is largely administered by the Ministry of Health and Ghana Health Services. The healthcare system has five levels of providers: health posts, health centers and clinics, district hospitals, regional hospitals and tertiary hospitals. Health posts are the first level of primary care for rural areas.

These programs are funded by the government of Ghana, financial credits, Internally Generated Fund (IGF), and Donors-pooled Health Fund.[6] Hospitals and clinics run by Christian Health Association of Ghana also provide healthcare services. There are 200 hospitals in Ghana. Some for-profit clinics exist, but they provide less than 2% of health care services.

Health care is very variable through Ghana. Urban centres are well served, and contain most hospitals, clinics, and pharmacies in the country. Rural areas often have no modern health care. Patients in these areas either rely on traditional African medicine, or travel great distances for health care. In 2005, Ghana spent 6.2% of GDP on health care, or US$30 per capita. Of that, approximately 34% was government expenditure.[7]

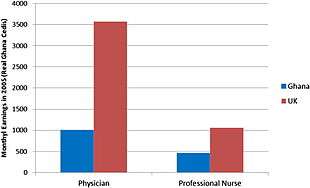

In 2015, life expectancy at birth was 66.18 years with males at 63.76 years and females at 68.66 years.[8] Infant mortality is at 37.37 per 1000 live births.[9] The total fertility rate is 4.06 children per woman among the 15 million Ghanaian nationals. In 2010, there were about 15 physicians and 93 nurses per 100,000 persons.[10]

In 2010, 5.2% of Ghana's GDP was spent on health,[11] and all Ghanaian citizens had access to primary health care. Ghanaian citizens make up 97.5% of Ghana's population.[12] Ghana's universal health care system has been described as the most successful healthcare system on the African continent by the renowned business magnate and tycoon Bill Gates.[12]

National Health Insurance

| National Health Insurance Scheme | |

_logo.jpg) | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 2003 |

| Jurisdiction |

|

| Parent agency | Parliament of Ghana |

| Website | Official Website |

Ghana has a universal health care system, National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS),[13] and until the establishment of the National Health Insurance Scheme, many people died because they did not have money to pay for their health care needs when they were taken ill. The system of health which operated prior to the establishment of the NHIS was known as the "Cash and Carry" system. Under this system, the health need of an individual was only attended to after initial payment for the service was made.[14] Even in cases when patients had been brought into the hospital on emergencies, it was required that money was paid at every point of service delivery. When the country returned to democratic rule in 1992, its health care sector started seeing improvements in terms of:

- Service delivery

- Human resource improvement

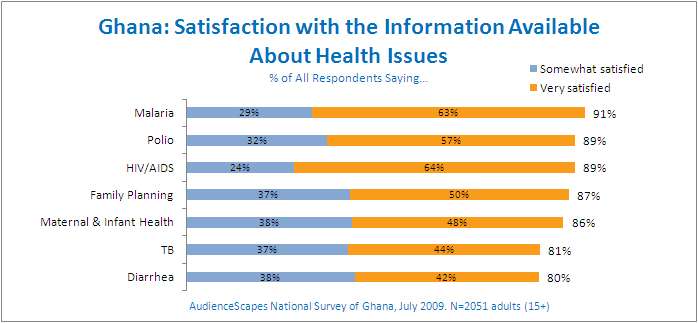

- Public education about health condition

even with these initiatives in place, many still could not access health care services because of the cash and carry system.[15]

The idea for the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) in Ghana was conceived by former president John Kufuor who when seeking the mandate of the people in the 2000 elections, promised to abolish the “cash and carry system” of health delivery.[16] Upon becoming president, former president Kufuor pushed through his idea of getting rid of “cash and carry” and replacing it with an equitable insurance scheme that ensured that treatment was provided first before payment. In 2003, the scheme was passed into law. Under the law, there was the establishment of National Health Insurance Authority which licenses, monitors and regulates the operation of health insurance schemes in Ghana. Like many countries in the world, Ghana's health insurance was fashioned out to meet specific needs of its citizens. Since its inception, the country's health facilities have seen constant rise in patient numbers and a considerable reduction in deaths.

Disease

According to the World Health Organization, the most common diseases in Ghana include those endemic to sub-Saharan African countries, particularly: cholera, typhoid, pulmonary tuberculosis, anthrax, pertussis, tetanus, chicken pox, yellow fever, measles, infectious hepatitis, trachoma, malaria, HIV and schistosomiasis. Though not as common, other regularly treated diseases include dracunculiasis, dysentery, river blindness or onchocerciasis, several kinds of pneumonia, dehydration, venereal diseases, and poliomyelitis.[17]

In 1994, the WHO reported malaria and measles were the most common causes of premature death. In 1994, 70 percent of deaths in children under five were caused by an infection compounded by malnutrition.[17] A 2011 report by the Ghana Health Service said that malaria was the primary cause of morbidity and about 32.5 percent of people admitted to Ghanaian medical facilities were admitted because of malaria.[18]

The most recent report from the WHO in 2012 identifies the top causes of death in Ghana as lower respiratory infections (11%), Stroke (9%), Malaria (8%), ischemic heart disease (6%), HIV/AIDS (5%), preterm birth complications (4%), birth asphyxia and birth trauma (4%), meningitis (3%), and protein-energy malnutrition (3%).[19] The life expectance for women is 63 years while for men, it is 60 years.[19] The Infant mortality rate is 41 out of every 1000 live births.[19]

Malaria

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, malaria was the third leading cause of death and accounted for 8% of all deaths in Ghana in 2012 despite the fact that malaria is preventable and curable.[19] Malaria occurs every year and affects people of all ages and demographics with women and children under 5 being the most vulnerable groups.[20] In addition, poor communities disproportionately are affected by infectious diseases when compared to wealthy communities due to lack of access to mosquito nets, adequate healthcare, and anti-malaria medication.[2] According to the 2014 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey, the prevalence of malaria in children ages 6 months to 5 years is 36%.[20]

The CDC, Ministry of Health, and Ghana Health Services collaborate to develop and implement malaria control initiatives such as insecticide treated mosquito nets, indoor residual spraying, improving diagnostics, research, and case management.[19] Insecticide treated mosquito nets have been identified as a cost-effective and sustainable public health method to combat malarial infections.[20] The Ministry of Health and the Ghana Health Service mass distribute the nets free of charge at schools and clinics. At least one Insecticide-treated mosquito net is owned by 68% of all households in Ghana; however, the Ghana Health and Demographic Survey sees large gaps between insecticide treated mosquito net ownership and use meaning that many with access to the nets are not effectively using them.[20]

HIV/AIDS

Like other countries worldwide, HIV/AIDS is present in Ghana.[21] In 2014, the estimated people that had HIV were 290,000 people out of Ghana's entire population of 27,499,924.[22] In 2014, 2.0% of Ghanaian adults ages 15–49 were HIV positive and less than 1% of people ages 15–24 were HIV positive.[20] HIV is higher in urban areas than in rural areas with prevalences rates of 2.4% and 1.7% respectively.[20] Although 70% of women and 82% of men have knowledge and use of HIV awareness and prevention methods, HIV/AIDS remains a large common health problem as many individuals do not consistently use a condom, have multiple partners, and fail to get HIV/AIDS testing.[20]

In response to the HIV epidemic, the Government of Ghana established the Ghana AIDS Commission, which coordinates efforts amongst international organizations and other parties to support education about eradication of HIV/AIDS throughout Ghana by the year 2022.[21] The CDC, alongside Ghana's Ministry of Health and Ghana Health Services, is also active in combating HIV/AIDS through improving Ghana's HIV/AIDS data collection and analysis methods in an effort to effectively allocate resources specific to each community's need.[19]

Chronic Diseases

Though largely ignored by healthcare, public health, and governmental policies, chronic disease prevalence and mortality rates have increased in the present day.[2] Epidemiologists have seen an overall rise in mortality rates caused by chronic diseases compared to pre-independence data that attributed most causes of death to infectious diseases across communities and economic strata.[2] This shift in causes of death from mostly chronic diseases and among wealthy urban populations to a mixture of chronic and communicable diseases in poorer populations reflects increasing life expectancy rates and differences in access to healthcare among differing communities.[2] In addition, chronic diseases receive less attention as a major public health crisis when compared to infectious diseases due Ghana's healthcare system historically and currently placing priority on combating infectious diseases compounded by inadequate financial and human resources.[23]

Chronic diseases have a long history in Africa with early records describing liver cancer in 1817, sickle cell disease in 1866, stroke in the 1920s and studies conducted since the 1950s containing prevalence rates and other important statistics for hypertension, diabetes, cancers, and sickle cell disease.[23] Previously the seventh cause of death in 1953, cardiovascular disease became the number one cause of death in 2001. By 2003 four chronic diseases, stroke, hypertension, diabetes and cancer, had become among the top ten causes of death in Ghana.[23] According to Ghana’s 2014 Demographics and Health Survey, 40% of men and 25% of women are overweight with previous data showing a 10% prevalence rate in women in 1993.[20] Hypertension had a national prevalence rate of 28.7% in 2006.[23]

Women's health

The health of women in Ghana is critical for national development. Women’s health issues in the country are largely centered on nutrition, reproductive health and family planning.[24] Reproduction is the source of many health problems for women in Ghana. The Ghana Living Standards Survey Report of the Fifth Round revealed that about 96.4% of women reported that they, or their partners, were using modern forms of contraception.[25]

This statistic has significant importance in reducing the spread of HIV/AIDS, which affected 120,000 women in Ghana in 2012 (of the 200,000 people living with the disease in Ghana in 2012).[26] Interventions for improving the health of women in Ghana, such as the Ghana Reproductive Health Strategic Plan 2007-2011, focus on maternal morbidity and mortality, contraceptive use and family planning services, and total empowerment of women.[27]

Maternal and child health care

The 2015 maternal mortality rate per 100,000 births for Ghana was 319.[28] This is compared to 409.2 in 2008 and 549 in 1990. The under 5 mortality rate, per 1,000 births is 72 and the neonatal mortality as a percentage of under 5's mortality is 39. In Ghana the number of midwives per 1,000 live births is 5 and the lifetime risk of death for pregnant women 1 in 66.[29]

Breast cancer

In Ghana, breast cancer is the leading malignancy.[30] In 2007, breast cancer accounted for 15.4% of all malignancies, and this number increases annually.[30] Roughly 70% of women who are diagnosed with breast cancer in Ghana are in the advanced stages of the disease.[31] In addition, a recent study has shown that women in Ghana are more likely to be diagnosed with high-grade tumors that are negative for expression of the estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and the HER2/neu marker.[32] These triple negative breast tumors are more aggressive and result in higher breast cancer mortality rates.[32]

Explanations for the delayed presentation among women in Ghana have been traced to the cost of, and access to, routine screening mammography.[31][33] Furthermore, women with breast cancer in Ghana describe a feeling of hopelessness and helplessness, largely due to their belief in fatalism, which contributes to denial as a means of coping.[33] Mayo et al. (2003) concludes, however, that lack of awareness may be a more critical variable than fatalism in explaining health care decisions among women in Ghana.

Over the past decade, international delegations and nongovernmental organizations have started responding to the growing problem of breast cancer in Ghana. In particular, the Breast Health Global Initiative, the Zurak Cancer Foundation,[34] and Susan G. Komen for the Cure are helping to increase early detection and reduce the breast cancer mortality rate in the country. Through public education, awareness, training, and particularly promotion of early detection practices, international aid groups have helped in improving the situation in Ghana.[35]

Water supply and sanitation

Since 1994, the water supply and sanitation sector has been gradually modernized through the creation of an autonomous regulatory agency, introduction of private sector participation, and decentralization of the rural supply to 138 districts, where user participation is encouraged. The reforms aim at increasing cost recovery and a modernization of the urban utility Ghana Water Company Ltd. (GWCL), as well as of rural water supply systems.[36] The National Water Policy (NWP), launched at the beginning of 2008, seeks to introduce a comprehensive sector policy.[37]

Water resources

Ghana is well endowed with water resources. The Volta River system basin, consisting of the Oti River, Daka River, Pru River, Sene River and Afram River as well as the White Volta and Black Volta rivers, covers 70% of Ghana's total land area. Another 22% of Ghana is covered by the southwestern river system watershed comprising the Bia River, Tano River, Ankobra River and Pra River. The coastal river system watershed, comprising the Ochi-Nawuka River, Ochi-Amissah River, Ayensu River, Densu River and Tordzie River, covers the remaining 8% of Ghana.

Furthermore, groundwater in Ghana is available in mesozoic and cenozoic sedimentary rocks and in sedimentary formations underlying the Volta Basin. Lake Volta, with a surface of 8,500 km², is the Earth's largest artificial lake. In all, the total actual renewable water resources are estimated to be 53.2 billion m³ per year.[38]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Twumasi, Patrick (1981-04-01). "Colonialism and international health: A study in social change in Ghana". Social Science & Medicine. Part B: Medical Anthropology. 15 (2): 147–151. doi:10.1016/0160-7987(81)90037-5. ISSN 0160-7987.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Agyei-Mensah, Samuel; Aikins, Ama de-Graft (2010-09-01). "Epidemiological Transition and the Double Burden of Disease in Accra, Ghana". Journal of Urban Health. 87 (5): 879–897. doi:10.1007/s11524-010-9492-y. ISSN 1099-3460. PMC 2937133.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Democratic demands and social policies: the politics of health reform in Ghana on JSTOR". JSTOR 23018898.

- 1 2 3 4 "Ghana : a country study". The Library of Congress. Retrieved 2018-05-07.

- 1 2 La Verle Berry, ed. (1994). "HEALTH AND WELFARE". Ghana: A Country Study.

- ↑ Canagarajah, Sudharshan; Ye, Xiao (April 2001). Public Health and Education Spending in Ghana in 1992-98 (PDF). World Bank Publication. p. 21.

- ↑ "WHO Statistical Information System". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- ↑ Field Listing :: Life expectancy at birth.cia.gov. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- ↑ Field Listing :: Infant mortality rate.cia.gov. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- ↑ "Afro.who.int" (PDF). Afro.who.int. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 January 2010. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- ↑ Field Listing :: Health expenditures.cia.gov. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- 1 2 "These are the countries where I'm the least known" – Bill Gates visits Ghana". TheJournal.ie. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ↑ "National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS)". nhis.gov.gh. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- ↑ "National Health Insurance Scheme" (PDF).

- ↑ Warren, D. M.; Tregoning, Mary Ann (1979). "Indigenous Healers and Primary Health Care in Ghana". Medical Anthropology Newsletter. 11 (1): 11–13. JSTOR 648386.

- ↑ Health Insurance in Ghana

- 1 2 La Verle Berry, ed. (1994). "Healthcare". Ghana: A Country Study.

- ↑ Akapule, Samuel Adadi (April 5, 2011). "Malaria Bites into Economic Development". Ghana News Agency.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "CDC Global Health - Ghana". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2018-04-09.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Ghana Demographic and Health Survey 2014" (PDF). October 2014.

- 1 2 "Ghana HIV and AIDS estimates (2012)". unaids.org. UNAIDS. 2012.

- ↑ "CIA WORLD FACTBOOK - Report". Retrieved 12 August 2013. , "2010 Population and Housing Census" (PDF). Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 de-Graft Aikins, Ama (2007-12). "Ghana's neglected chronic disease epidemic: a developmental challenge". Ghana Medical Journal. 41 (4): 154–159. PMC 2350116. PMID 18464903. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Ghana Demographic and Health Survey Report" (PDF). Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research.

- ↑ "Ghana Living Standards Survey 4" (PDF). Ghana Statistical Service.

- ↑ "Give The Ghanaian Woman An Option In Protection". GhanaWeb.

- ↑ "REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH STRATEGIC PLAN 2007-2011" (PDF). Ghana Health Service.

- ↑ Field Listing :: Maternal mortality rate.cia.gov. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- ↑ "The State of World's Midwifery 2011: Delivering Health, Saving Lives". United Nations Population Fund. Retrieved August 2011. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - 1 2 Clegg-Lamptey, J.N.A; Hodasi, W (2007). "A study of breast cancer in Korle Bu teaching hospital: assessing the impact of health education". Ghana Medical Journal. 41 (2): 72–77. PMC 2002569. PMID 17925846.

- 1 2 Kirby, A (2005). "Early Detection of Breast Cancer in Ghana, West Africa". Journal of Investigative Medicine. 53: 580.

- 1 2 Stark, A.; Kleer, Celina G.; Martin, Iman; Awuah, Baffour; Nsiah-Asare, Anthony; Takyi, Valerie; Braman, Maria; e. Quayson, Solomon; et al. (2010). "African Ancestry and Higher Prevalence of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Findings from an international study". Cancer. 116 (21): 4926–4932. doi:10.1002/cncr.25276. PMC 3138711. PMID 20629078.

- 1 2 Mayo; Hunter, Anita; et al. (2003). "Fatalism Toward Breast Cancer Among the Women of Ghana". Healthcare for Women International. 24 (7): 608–615. doi:10.1080/07399330390217752.

- ↑ "Zurak Cancer Foundation". zurakcancerfoundation.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2017-07-26.

- ↑ "BHGI and Ghana combat breast cancer together".

- ↑ WaterAid. "National Water Sector Assessment, Ghana" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-03-26.

- ↑ Ghanaian Water Resources Commission. "National Water Policy". Archived from the original on 2008-06-02. Retrieved 2008-03-26.

- ↑ Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. "Ghana Country Overview" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-02-19. Retrieved 2008-03-25. , p. 3-4