Health in Ethiopia

Health in Ethiopia has improved markedly since the early 2000s, with government leadership playing a key role in mobilizing resources and ensuring that they are used effectively. A central feature of the sector is the priority given to the Health Extension Programme, which delivers cost-effective basic services that enhance equity and provide care to millions of women, men and children. The development and delivery of the Health Extension Program, and its lasting success, is an example of how a low-income country can still improve access to health services with creativity and dedication.[1]

Overview

Ethiopia is the second most populous country in sub-Saharan Africa, with a population of over 94.1 million people the population of goes to 104 million (CSA projection). The country introduced a federal government structure in 1994 composed of nine Regional States: Afar, Amhara, Oromia, Somali, Benishangul Gumuz, Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples Region (SNNPR), Gambela, Tigray and Harrari and two city Administrations (Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa). The Regional States are administratively divided into 78 Zones and 710 800 Woredas.[2]

Health Status Overview

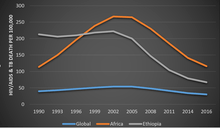

Sub-Saharan Africa is one of the poorest corner of the world where major health related challenges are concentrated. The growing morbidity and mortality related burden of non-communicable diseases and Injury has posed unbearable challenge to the already staggering continent from the age long communicable disease era. Though there is minimal progress over the mortality rates from infectious diseases, mainly from the decline in HIV related mortality, still there is a lot to be addressed. Ethiopia, a low income country located in the eastern sub-Saharan African region has almost similar morbidity and mortality pattern.

The fact that the country achieved MDG 4, reducing the child mortality and the decline of HIV mortality has helped the life expectancy to increase to 65.2yr in 2015 from 46.6yr in 1990. The Under 5 mortality rate and Infant mortality rate has dropped from 203 and 122 in 1990 to 61.3 and 41.4 in 2015. The ministry of health has achieved this through the Health Extension Program by using a special implementation platform called Women Development Army.

| Health Indicator | 1950 | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U5MR | 329 | 275 | 243 | 240 | 203 | 144 | 61.3 |

| IMR | - | 162 | 143 | 143 | 122 | 89.5 | 41.4 |

| Life Expectancy (Yr) | 33.8 | 39 | 43.7 | 44.6 | 46.6 | 51/1 | 65.2 |

Ethiopia experiences a triple burden of disease mainly attributed to communicable infectious diseases and nutritional deficiencies, NCD and traffic accident.[4] Shortage and high turnover of human resource and inadequacy of essential drugs and supplies have also contributed to the burden. However, there has been encouraging improvements in the coverage and utilization of the health service over the periods of implementation of Health Sector Development Plan (HSDP).

HSDP constitutes the health chapter of the national poverty reduction strategy and aims to increase immunization coverage and decrease under-five mortality at large. The health service currently reaches about 72% of the population and The Federal Ministry of Health aims to reach 85% of the population by 2009 through the Health Extension Program (HEP) [1]. The HEP is designed to deliver health promotion, immunization and other disease prevention measures along with a limited number of high-impact curative interventions.[5]

TB and Leprosy Control Program (TLCP)

1. History of Tuberculosis and Leprosy control Program in Ethiopia

Tuberculosis has been identified as one of the major public health problems in Ethiopia for the past five decades. The effort to control tuberculosis began in the early 60s with the establishment of TB centers and sanatoria in three major urban areas in the country. The Central Office (CO) of the National Tuberculosis Control Program (NTCP) was established in 1976. From the very beginning the CO had serious problems in securing sufficient budget and skilled human resource. In 1992, a well-organized TB program incorporating standardized directly observed short course treatment (DOTS) was implemented in a few pilot areas of the country.

An organized leprosy control program was established within the Ministry of Health in 1956, with a detailed policy in 1969. In the following decades, leprosy control was strongly supported by the All African Leprosy and Rehabilitation Training Institute (ALERT) and the German Leprosy Relief Association (GLRA). This vertical program was well funded and has scored notable achievements in reducing the prevalence of leprosy, especially after the introduction of Multiple Drug Therapy (MDT) in 1983. This has encouraged Ethiopia to consider integration of the vertical leprosy control program with in the general health services. The two programs were merged to being the National Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control program (NTLCP), and coordinated under the technical leadership of the CO from 1994.

2. TB prevalence, incidence and mortality rates in Ethiopia

The most recent WHO global report classifies Ethiopia as one of the top 30 high burden countries for TB, TB/HIV and MDR-TB.[6] The TB prevalence estimates in Ethiopia shows a steady decline since 1995 with an average rate of 4% per year, which is accentuated in the last five years (annual decline of 5.4%). Likewise, the estimates for TB incidence reached a peak value of 431/100,000 population in 1997, and has been declining at an average rate of 3.9% per year since 1998, with annual decline of 6% within the last five years. The incidence estimate for all forms of TB in 2015 is 192/100,000 population. TB mortality rate has also been declining steadily since 1990 and reached 26/100,000 population in 2015. The decline in prevalence rate for all forms of TB has declined from 426/100,100 in 1990 to 200/100,000 population in 2014 (53% reduction). Similarly, the TB incidence rate has dropped from 369 in 1990 to 192/100,000 population in 2015 (48% reduction), after a peak of 421/100,000 in 2000. Furthermore, TB related mortality rate has been declining steadily over the last decade from 89/100,000 in 1990 to 26/100,000 in 2015 (70% reduction from 1990 level).

In 2011, the first population based national survey shows a prevalence rate of 108/100,000 population smear positive TB among adults, and 277/100,000 population bacteriologically confirmed TB cases.[7] The prevalence of TB for all groups in Ethiopia was 240/100,000 populations in the same year. This finding indicates that the actual TB prevalence and incidence rates in Ethiopia are lower than the WHO estimates. Additionally, the survey showed a higher prevalence rates for smear positive and bacteriologically confirmed TB in pastoralist communities. However, pertaining to its methodology, the survey did not produce further disaggregated sub-national estimates.

Health Extension Programme (HEP)

DESIGN AND IMPLEMENTATION OF THE HEALTH EXTENSION PROGRAM In 1993 the government published the country's first health policy in 50 years, articulating a vision for the health care sector development. The policy fully reorganized the health services delivery system as contributing positively to the country's overall socioeconomic development efforts. Its major themes focus on:

- Democratization and decentralization of health system;

- Expanding the primary health care system and emphasizing preventive, promotional, and basic curative health services; and

- Encouraging partnerships and the participation of the community and nongovernmental actors.

In pursuit of the health policy goals of improving the health status of the Ethiopian population and to implement the health policy, a Health Sector development Program (HSDP)was developed every five years beginning in 1997/98. HSDP II included a strategy, called the Health Extension Program (HEP), for scaling up an institutionalized primary health care system.[8] The Health Extension program was introduced under HSDP II in 2002/03 with a fundamental philosophy that if the right health knowledge and skill is transferred, households can take responsibility for producing and maintaining their own health.The Health Extension Programme (HEP) is a community-based intervention designed to make basic health services accessible to the rural and underserved segments of the population.[9] The HEP was launched in the four big agrarian regions, expanded to the remaining regions in subsequent years. The program has been tailored to the particular requirements of pastoral and agropastoral communities and, more recently, to urban communities.[10]

Figure 2.9, Trends in the Training of HEWs, EFY 1997–2002 Under HSDP III it was planned to cover all rural kebeles with the HEP with the aim of achieving universal PHC coverage by 2008 through vigorous and incremental implementation of the programme nationwide. From the very start HEP was supported with the development of 16 different health intervention packages to be delivered by HEWs at community level. These packages along with implementation guidelines were made available to implementers as well as to technical and vocational training institutions. The packages have been subjected to modification commensurate with the life style of the pastoralist population. The training of all female HEWs have been progressing well with encouraging sign and endorsement of community's acceptance and demand for HEP services. HEP services are organized along geographic lines (kebeles – lowest administrative government unit): construction of a comprehensive network of "primary health care units (PHCU)" throughout the country with one health post in every rural kebele of 5000 people linked to referral health center. A health post is a two-room structure of most peripheral health care unit and the first level for the provision of healthcare for the community, emphasizing preventive and promotive care. They serve as the operational center for HEP.[11]

By the end of HSDP III, a total of 33,819 HEWs were trained and deployed surpassing HSDP III target and reaching 102.4 from the required 33,033 HEWs. Model households who have been trained and graduated have reached a cumulative total of 4,061,532 from an eligible total of 15,850,457 households. This only represented a coverage of 26% leaving a huge gap of more than 11 million households to be trained and graduate thus requiring a progressive and sustained efforts at all regions and levels of the health care system.

Figure 2.10: Trends of Construction of Health Posts, EFY 1997–2002 In terms of the construction of HPs as a home base for the delivery of HEP at community level, the achievement so far has encouragingly indicate there has been tremendous progress. The total number of HPs has increased from the baseline of 6,191 in 2004/05 to 14,416 in 2009/10, more than doubling in a space of only four years. This figure however showed an achievement rate of 89% compared to the planned target of 100% under HSDP III. Equipping Health posts with medical kits remain a major challenge during the implementation years of HSDP III where only 83.1% or 13,510 HPs out the planned target of 16,253 HPs were fully equipped. Other major activities in support of HEP include the establishment of HEP departments at regional levels and respective structures at zonal and woreda levels all aimed at strengthening the management support to HEP. Technical guideline for HEP Supportive supervision technical, reference books for rural HEP and manuals for school health program were prepared and have been adopted in the light of the BPR. Moreover, implementation Manual for Pastoralist and semi-pastoralist areas was finalized and has been distributed to respective regions. As part of the implementation training and deployment were completed for 2,566 HEP supervisors achieving 80.2% coverage against the plan of 3,200. In order to expand Urban HEP in seven regions of the country, 15 HEP packages along with implementation manual have been developed and distributed for implementation. Training and deployment of Urban HEWs has already in progress in Tigray, Amhara, Oromiya; SNNP, Harari, Dire Dawa; and Addis Ababa. Accordingly, these regions have trained and deployed a total of 2,319 Urban Health Extension workers achieving 42% of the required number.

Based on lessons from the successful implementation of the agrarian health extension program, the HEP has expanded to urban and pastoral areas. The HEP is intended to transfer ownership and responsibility of maintaining health to individual households so that communities are empowered to produce their own health. The focus of HEP is disease prevention and health promotion, with limited curative care. It is the healthcare service delivery mechanism of the people, by the people, and for the people by involving the community in the whole process of healthcare delivery and by encouraging them to maintain their own health. The program involves women in decision-making processes and promotes community ownership, empowerment, autonomy and self-reliance. Ethiopia has come a long way in improving the health status of its people as evidenced by the achievement of most health related Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).The progress has been rapid after the inception of the HEP.[12]

Initiation of the second generation HEP

As literacy and socioeconomic status improves, the demand for quality service is also increasing. Besides, changes in the demographic trends, epidemiology and mushrooming urbanization require more comprehensive services covering a wide range and quality of curative, promotive and preventive services. To respond to the rapidly changing situations, the Government is currently revisiting the HEP. As addressing equity and quality of health services are the main focuses of the new Ethiopian Health Sector Transformation Plan (HSTP), most basic services will be shifted and responsibility will be shared to the community level structures. Therefore, improving the competence of HEWs and the Women's Development Army (WDA) is crucial. Components of the second generation HEP. The components of the health extension program varies based on where it is implemented. The second generation rural HEP will include: upgrading HEWs to level four Community Health Nurses, renovation and expansion of health posts, equipping and supplying health posts with the necessary equipment and supplies, shifting basic services to the community level and institutionalizing the WDA platform.

In cities and urban areas, the Family Health Team (FHT) approach will be introduced. The FHT approach will consist of multiple professionals who will address the complex situation and health problems of urban settings. The FHT will be composed of clinicians, public health professionals, environmental technicians, other health professional, social workers and health extension professionals to provide services for urban dwellers which have unique types of health needs. The community/household level health services will be geared towards the neediest segment of the population - the urban poor, and those otherwise unreached to address inequalities in accessing quality health care. The third type of HEP will be the pastoralist HEP. Considering the varied nature of the community residing in the pastoralist and developing regions, the Ministry of Health, along with the Regional Health Bureaus is committed to developing a unique strategy to address pastoralist communities' health issues.[12]

Health systems

The following sections summarize progress made in the area of health systems in Ethiopia.

Health sector reform

Health sector reform in Ethiopia is an undergoing process as a comprehensive endeavor in the socio-economic reform that started with Civil Service Reform covering the entire public sector of the country. As part of this national effort, the reform in the health sector has been intensified through the application of a new concept known as Business Process Reengineering (BPR). BPR has been used as a tool for a comprehensive analysis, redesign and revamping of the health sector in Ethiopia. As a process itself forms a fundamental rethinking and requires a purposeful and radical redesign of health business processes to achieve dramatic improvements in critical, contemporary measures of performance such as cost, quality, service and speed. The BPR is a country led, multisectoral undertaking implemented as a comprehensive approach to the government's civil service reform. The purpose of the PBR in the context of the health sector was to establish customer focused institutions, rapid scaling up of health services and enhancing the quality of care in order to improve the health status of the Ethiopian people as indicated in the mission of the health sector. Following a deeper and systematic analysis of the "as is" situation at all levels of the health system, including health facilities, the sector has brought in innovative approaches including, benchmarking best practices, redesign new processes, revising organizational structures and a selection of 8 core process and 5 support processes. The new 8 core processes are; Health Care Delivery (which are now divided into four directorates which are MCH, DPC, Medical services and health extension and primary care directorates); Public Health Emergency Management; Research and Technology Transfer; Pharmaceutical Supply; Resource Mobilization, Health Insurance (insurance becomes an agency); Health and Health Related Services and Product Regulation; Health Infrastructure, Expansion and Rehabilitation; and Policy, Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation. The 5 support processes designed were: Human Resources Development /Management (which is currently divided into human resource Administration, human resource development and health professional licensing); Procurement and Finance, and General Service; Program-Based Audit; Public Relations and Legal Services and gender directorate. The health sector reform changed the agency's structure becomes the, which became the pharmaceutical and supply agency, Ethiopian public health institute, Ethiopia primary care training institute, Ethiopian Insurance agency, blood bank service, Armani Hansen research institute, food medicine and health professional control regulatory authority, and different directorates within the FMOH.[13]

Subsequent to this, series of training sessions have been given to managers and technicians at all levels, There has been changes in staff deployment and specific job assignments including recruitment of new staff leading to progressive implementations under the close oversight of the top health leadership.

Health facility construction and expansion

Since HSDP I, major activities under the health facility construction, expansion, rehabilitation, furnishing and equipping focused mainly on the PHC facilities: HPs and HCs and to a certain extent hospitals. By the end of HSDP II, the number of public HCs has increased by 70% from 412 in 1996/97 to 519 in 2003/04. For the same periods, the number of HPs increased from 76 in 1996/97 to 2,899. The number of hospitals (both public and private) also increased from 87 in 1996/97 to 126 in 2003/04. There has been also considerable health facility rehabilitation program and furnishing during the HSDP I and HSDP II including improvements in support facilities. As a result, the potential health service coverage increased from 45% in 1996/97 to 64.02% by 2003/04.

The HSDP III plan was to further expand these and other services with the aim of achieving universal health service coverage by the end of 2008 and also improving the delivery of primary health care services to the most neglected rural population. This was an extension of the Accelerated Expansion of Primary Health Service Coverage that has been launched in the midterm of HSDP II. The HSDP III target in this component has been to attain a 100% general potential health service coverage by availing 3200 HCs through construction, equipping and furnishing of 253 new HCs and upgrading 1,457 HSs to HC level and also upgrading of 30% of HC to enable them perform EmONC services

| Facility | HSDP I (1996/7) | HSDP II (2003/2004) | HSDP III (2010) | HSTP (2015)[14] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HP | 76 | 2,899 | 14,416 | 16,440 |

| HC | 412 | 519 | 2689 | 3,547 |

| Hospitals | 87 | 126 | 195 | 311 |

Progresses in the Health facility construction, upgrading and equipping under HSDP III were remarkable. Through increasing construction works, the number of HPs has reached 14,416 achieving 88.7% of the target by 2009/10. Moreover, there are now 2,689 HCs accounting for 84% of the 3,200 HCs target by the end of HSDP-III. Additional 511 HCs are under construction to reach the 100% target. At the beginning of HSDP III, there were 82 all types of Hospitals (37 District, 39 Zonal and 6 Specialized Hospital). The planned target under HSDP III was to increase the number of hospitals to 89 (42 district and 41 zonal). However, the 2008/09 report showed that the target has been surpassed with current total of 111 Public Hospitals (nearly 25% increase).

In addition, 12,292 health posts have been equipped which represents 75.6% of the target of equipping 16,253 health posts. Equipment for 2,299 HCs was accomplished and for an additional 390 HCs is underway. The rest 511 new HCs under construction will be equipped following their completion. . Moreover, the construction of 21 blood banks in six regions is on progress with 95% of the construction completed in 2009 and the preparation of a National Laboratory Master Plan has also been already completed. currently the HSDP IV is fianlized and the new Health sector transformation plan is implemting which remains the next two years of Ethiopian fiscal year. with regard to the health facilities constraction the number of health centers is more than 3500 and the number of hospitals are about 300 which makes the potiential priamry health service coverage is 100%. in the newly designed health sector transformation plan there are mainly 15 strategic objectives and four transformation agendas are included. the major transformation agenda are words transformation, information revolution, compassionate, respectful and caring health professionals, and equity and quality of health care delivery. which each transformation agendas has their montiorning indicators to see the progress in each of them.[15]

Health human resource development

Human resource development (HRD) has been a key component in the successive HSDPs. It has been one of the key components in HSDP III with the main objective of improving the staffing level at various levels as well as to establish implementation of transparent and accountable Human Resource Management (HRM) at all levels. It is envisaged that this will be made possible through increasing the number and capacity of training institutions, use health institutions as a training center as well as through establishing a platform for the effective implementation of CSRP and introducing incentive packages.

With the aims of improving the overall HRH situation in the country the government has initiated BPR process that thoroughly analyzed the HRH situation in the country. Based on this a comprehensive HRH strategic plan that details the HRH planning, management, education, training and skill development, legal framework as well as financing mechanism have also been developed through involvement of relevant stakeholders, development partners and international consultants. To improve the staffing number and composition at various levels, taking into account the HRH requirement for the universal Primary Health Care (PHC) coverage by the end of HSDP III period, the focus has been on scaling up the training of community and Mid-Level Health Professionals (MLHPs). With regard to community level professionals a total of 31,831 HEWs have been trained and deployed to meet the HRH requirement for HEP. Similarly, Accelerated Health Officer Training Program (AHOTP) was launched in 2005, in five universities and 20 hospitals to address the clinical service and public health sector management need at district level. So far more than 5,000 health officer trainees (generic and upgrade) have been enrolled and 3,573 Health officers were graduated and deployed. In addition; to address the HRH need for Comprehensive Emergency Obstetric Care (CEmONC) and other emergency surgery service need at PHC level, curriculum for masters program on Emergency Surgery has been developed and training has been started in five universities. To address the critical shortage and maldistribution of doctors, in addition to the existing medical schools a new medical school that uses innovative approach has been opened in St. Paul's Hospital's Millennium Medical School. A new integrated curriculum that enhances the clinical skill and social accountability of medical doctors has also been developed.

Overall, the available professionals at the end of HSDP III compared to the HSDP III targets shows that the target has been met for community level and most of MLHP. The number has also significantly increased compared to the levels in the previous HSDP. Given the country's emphasis on expanding primary healthcare services, there was a focus on growing the low and mid-level health workforce. The effort to increase mid-level health workers gathered momentum in 2003 when the government introduced the health extension program, Ethiopia's flagship program. This policy prioritization of massively expanding the primary care health workforce was translated into concrete targets and strategic initiatives that were included in the successive health sector development programs III and IV implemented from 2007–2015. A human resources for health situation analysis conducted in 2015/2016showed that the human resources development and management targets set out in the HSDP-IV were achieved through sustained expansion of health workers, including an increased number of education and training programs for various cadres of health professionals. For example, between 2009 and 2014/15:

- The number of medical schools has increased from 7 to 35 (28 Public and 7 Private)

- Annual enrollment in medical students has increased from 200 to 4,000.

- The number of physicians in the country has increased from 1,540to 5,372.

- Midwifery teaching institutions have also increased from 23 to 49.

- The number of midwives increased from 1,270 in 2009 to 11,349

Apart from these selected health professionals, overall health professionals to population ratio increased from 0.84 per 1000 in 2010 to 1.5 per 1000 in 2016. This is remarkable progress for a 5-year period. If the current pace is sustained, Ethiopia will be able to meet the minimum threshold of health professionals to population ratio of 2.3 per 1000 population, the 2025 benchmark set by the World Health Organization (WHO), for Sub-Saharan Africa.[16]

Pre-service Education The marked improvement in the availability of health workers is due to massive scale up of production in the last two decades. The number of health worker training public higher educational institutions has increased from 8 to 57. Of these, 34 are universities and hospital-based colleges offering degree programs while 23 are regional health science colleges offering technical and vocational qualifications (level 1 to 5). Private health science colleges have also flourished, with 24 institutions offering accredited programs as of 2012/2013. Specifically, the number of medical schools has risen to 33 (of which 5 are private) and public midwifery schools have reached 49. There has also been parallel expansion in enrollment and graduation outputs. Over sixty thousand health science students were enrolled in public higher education institutions; and an additional 15,834 in private higher educational institutions as of 2012/2013. Annual enrollment of health science students in public higher educational institutions reached close to 23,000 (58% in regional health science colleges) by 2014. Additionally, the annual intake of medical students rose by more than 2-fold from 1,462 in 2008 to 3,417 in 2014. Graduation output from higher educational institutions has increased by close to 16-fold from 1041 in 1999/2000 to 16,017 by 2012/2013. Ethiopia is on track in scaling up the quantity of health worker production. However, capacity and readiness of higher educational institutions to assure quality of education has not developed proportionally. The Government of Ethiopia allocates up to 4.6% of its GDP, which is one of the largest in Africa, on education. However, most of it is capital budget, with limited resources available to enhance the core mission of quality and relevance of higher education.[17]

Continuing professional development (CPD)

Continuing professional development (CDP) is an ongoing process of learning which ensures that health professionals have up-to-date training through the whole of their career. Although there are guidelines regarding continuing professional development and in-service training in the health sector, there is no active enforcement of them.[18] Local capacity to develop, offer, enforce, monitor and evaluate relevant and quality CPD activities is under-developed. CPD is not yet linked to re-licensure and career progression. Some in-service training are not always need-based, well-planned, coordinated, quality assured, monitored and evaluated for their effectiveness. IST is mostly face-to-face and group based with limited use of innovative and efficient in-service training modalities like on-the-job training, and blended learning approaches.[19]

| HR Category | End HSDP I | 1994 HSDP II | End 1997 HSDP III | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ! Total No | Ratio to population | Total No | Ratio to population | Total No | Ratio to Population | |

| All physicians | 1,888 | 1:35,603 | 1,996 | 1:35,604 | 2152 | 1: 34,986 |

| Specialist | 652 | 1:103,098 | 775 | 1:91,698 | 1151 | 1:62,783 |

| General practitioners | 1,236 | 1: 54,385 | 1221 | 1:58,203 | 1001 | 1:76,302 |

| Public health officers | 484 | 1:138,884 | 683 | 1:104,050 | 3,760 | 1: 20,638 |

| Nurses Bsc, & Diploma (except midwives) | 11,976 | 1:5,613 | 14,270 | 1: 4,980 | 20109 | 1: 4,895 |

| Midwives (Senior) | 862 | 1:77,981 | 1,274 | 1: 55,782 | 1379 | 1: 57,354 |

| Pharmacists | 118 | 1:569,661 | 172 | 1:413,174 | 661 | 1: 117,397 |

| Pharmacy Tech. | 793 | 1: 84,767 | 1171 | 1: 60,688 | 3013 | 1: 25,755 |

| Environmental HW | 971 | 1: 69,228 | 1169 | 1: 60,792 | 1,819 | 1: 42,660 |

| Laboratory technicians & technologists | 1,695 | 1:39,657 | 2,403 | 1: 29,574 | 2,989 | 1: 25,961 |

| Health Extension Workers | - | - | 2,737 | 1: 23,775 | 31,831 | 1: 2,437 |

Health care financing

The current Ethiopia health care financing strategy focus on financing of primary health care services in a sustainable manner. It envisions reaching universal health coverage by 2035. The prioritized initiatives are mobilizing adequate resources mainly from domestic sources, reducing out-of-pocket spending at the point of service use, enhancing efficiency and effectiveness, strengthening public private partnership and capacity development for improved health care financing. To operationalize the strategy, various reform measures were implemented. These reforms include: revenue retention and use at the health facility level; systematizing fee waiver system; standardization of exempted services; setting and revision of user fees; allowing establishment of private wing in public hospitals; outsourcing of non-clinical services ; and, promotion of health facility autonomy through establishment of a governance body; and establishment of health insurance system.

According to the 6th National Health Accounts (2013/14),[20] health service in Ethiopia is primarily financed from 4 sources: the federal and regional governments; grants and loans from bilateral and multilateral donors; non-governmental organizations and private contributions. The total health expenditure per capita has increased from $4.5 per capita in 1995/1966 to 20.77 in 2010/11 and $28.65 per capita in 2013/14.The share of total health expenditure coming from domestic sources has increased from 50 percent in 2010/11 to 64 percent in 2013/14.

Purchasing of services

While mobilizing sufficient public resources and organizing pooling to maximize re-distributive capacity are essential for achieving equitable and affordable health care access for all, it is of equal importance that collected resources be efficiently used in order to maximize and sustain the provision of benefits for the population. Strategic use of the purchasing function is the key health financing instrument for this purpose. The main purchasers of health service in Ethiopia are: the Ministry of Health; Regional Health Bureaus; District/Woreda Health Offices in the form of line-item budgets; Ethiopia Health Insurance Agency; and, other government entities that transfer budget to service providers to reimburse service delivery cost; and households in the form of user fee. There is fee waiver system to covers Indigents but with various challenges in implementation. The number of fee waiver beneficiaries has reached 2 million.[20] While this progress is encouraging, it constitutes less than 10% of the total population that lives below the poverty line in the country.

Indicators

| Indicator description | Value |

|---|---|

| Hospitals | 234[21] |

| Health centers | 3586[21] |

| Health posts | 11,446 |

| Health stations +NHC | 1,517 |

| Private clinics for profit | 1,788 |

| Private clinics not for profit | 271 |

| Pharmacies | 320 |

| Drug shops | 577 |

| Rural drug vendors | 2,121 |

Throughout the 1990s, the government, as part of its reconstruction program, devoted ever-increasing amounts of funding to the social and health sectors, which brought corresponding improvements in school enrollments, adult literacy, and infant mortality rates. These expenditures stagnated or declined during the 1998–2000 war with Eritrea, but in the years since, outlays for health have grown steadily. In 2000–2001, the budget allocation for the health sector was approximately US$144 million; health expenditures per capita were estimated at US$4.50, compared with US$10 on average in sub-Saharan Africa. In 2000 the country counted one hospital bed per 4,900 population and more than 27,000 people per primary health care facility. The physician to population ratio was 1:48,000, the nurse to population ratio, 1:12,000. Overall, there were 20 trained health providers per 100,000 inhabitants. These ratios have since shown some improvement. Health care is disproportionately available in urban centers; in rural areas where the vast majority of the population resides, access to health care varies from limited to nonexistent. As of the end of 2003, the United Nations (UN) reported that 4.4 percent of adults were infected with human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS); other estimates of the rate of infection ranged from a low of 7 percent to a high of 18 percent. Whatever the actual rate, the prevalence of HIV/AIDS has contributed to falling life expectancy since the early 1990s. According to the Ministry of Health, one-third of current young adult deaths are AIDS-related. Malnutrition is widespread, especially among children, as is food insecurity. Because of growing population pressure on agricultural and pastoral land, soil degradation, and severe droughts that have occurred each decade since the 1970s, per capita food production is declining. According to the UN and the World Bank, Ethiopia at present suffers from a structural food deficit such that even in the most productive years, at least 5 million Ethiopians require food relief.[23]

In 2002 the government embarked on a poverty reduction program that called for outlays in education, health, sanitation, and water. A polio vaccination campaign for 14 million children has been carried out, and a program to resettle some 2 million subsistence farmers is underway.[23] In 2003, the government launched the Health Extension Program which will provide universal primary health care coverage by 2009. This includes placing two government-salaried female Health Extension Workers (HEW) in every kebele, with the aim of shifting the emphasis of health care to prevention. About 2,700 HEWs completed their training by the end of 2004 at 11 technical and vocational education centers, while 7,000 HEWs were still in training in 2005, and over 30,000 HEWs were expected to complete their training by 2009. However, these trainees encountered a lack adequate facilities, which included classrooms, libraries, water, and latrines. The selection of trainees was flawed, with most being urban inhabitants and not from the rural villages they would be working in. Reimbursement was haphazard as trainees in some regions did not receive stipends while those in other regions did.[24] In January 2005, the government began distributing antiretroviral drugs, hoping to reach up to 30,000 HIV-infected adults.[23]

According to the head of the World Bank's Global HIV/AIDS Program, Ethiopia has only 1 medical doctor per 100,000 people.[25] However, the World Health Organization in its 2006 World Health Report gives a figure of 1936 physicians (for 2003),[26] which comes to about 2.6 per 100,000. There are 119 hospitals (12 in Addis Ababa alone) and 412 health centers in Ethiopia.[27] Globalization is said to affect the country, with many educated professionals leaving Ethiopia for a better economic opportunity in better-developed countries.

Ethiopia's main health problems are said to be communicable diseases caused by poor sanitation and malnutrition. These problems are exacerbated by the shortage of trained manpower and health facilities.[28] Ethiopia has a relatively low average life expectancy of 62/65 years.[29] Only 20 percent of children nationwide have been immunized against all six vaccine-preventable diseases: tuberculosis, diphtheria, whooping cough, tetanus, polio, and measles. Rates of immunization are less than 3 percent of children in Afar and Somali Regions and less than 20 percent in Amhara, Benishangul-Gumuz, and Gambela. In contrast, almost 70 percent of children have received all vaccinations in Addis Ababa and 43 percent in Dire Dawa; children in urban areas are three times as likely to be fully immunized as children living in rural areas.[30]

Maternal and child health

Maternal and child health program is a priority agenda of the government of Ethiopia and this has been clearly indicated on the currently being implemented strategic plan of the FDRE Ministry of health, called HSTP. Though Maternal and child health program is still one of the target area which needs much organized, systematic and focused effort, clear progress has been witnessed over years as per the Demographic health survey report of the country. The recent DHS in the country shows these steady changes.

Maternal health status could be assessed with many indicators of which Modern contraceptive use, skilled delivery and maternal mortality are some of the majors. Modern contraceptive use by currently married Ethiopian women has increased over 15years prior to the 2016 DHS. Jumping from 6% in 2000 to 27% and 35% in 2011 and 2016 respectively. The skilled delivery has increased from 10% in 2011 to 27.7% in 2016. The total fertility is declining but the changes are not that significant. The pregnancy related mortality has also dropped over the last three surveys and this could be attributed to the improvement on skilled delivery and family planning. The maternal mortality (if it could be used interchangeably with pregnancy related disease (with all the limitations)) is more than double the SDG target set for maternal mortality reduction (70/100,000live birth)

Now a days children are getting vaccinated better compared to the past two decades. The fact that Ethiopia is on the verge of eradicating polio could be a good evidence for that. The percentage of age 12 – 23 months who are fully vaccinated increased by 15% from 24% in 2011 to 39% in 2016. Childhood mortality has declined substantially since 2000. However, the change in neonatal mortality is not significant compared to post neonatal and child mortality. Reducing child mortality (MDG 3) has been achieved previously and if the effort is maintained the 2030 target of decreasing the under-five mortality to 25 could be met by the end of the target.

Traditional medicine

The low availability of health care professionals with modern medical training, together with lack of funds for medical services, leads to the preponderancy of less reliable traditional healers that use home-based therapies to heal common ailments. High rates of unemployment leave many Ethiopian citizens unable to support their families. In Ethiopia an increasing number of "false healers" using home-based medicines have grown with the rising population.[31] The differences between real and false healers are almost impossible to distinguish. However, only about ten percent of practicing healers are true Ethiopian healers. Much of the false practice can be attributed to commercialization of medicine and the high demand for healing. Both men and women are known to practice medicine from their homes. It is most commonly the men that dispense herbal medicine similar to an out of home pharmacy.[32]

Ethiopian healers are more commonly known as traditional medical practitioners. Before the onset of Christian missionaries and Medical Revolution sciences, traditional medicine was the only form of treatment available. Traditional healers extract healing ingredients from wild plants, animals and rare minerals. AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis and dysentery are the leading causes of disease-related death. Largely because of the costs, traditional medicine continues to be the most common form of medicine practiced. Many Ethiopians are unemployed which makes it difficult to pay for most medicinal treatments.[33] Ethiopian medicine is heavily reliant on magical and supernatural beliefs that have little or no relation to the actual disease itself. Many physical ailments are believed to be caused by the spiritual realm which is the reason healers are most likely to integrate spiritual and magical healing techniques. Traditional medicinal practice is strongly related to the rich cultural beliefs of Ethiopia, which explains the emphasis of its use.[34]

In Ethiopian culture there are two main theories of the cause of disease. The first is attributed to God or other supernatural forces, while the other is attributed to external factors such as unclean drinking water and unsanitary food. Most genetic diseases or deaths are viewed as the will of God. Miscarriages are thought to be the result of demonic spirits.[35]

One medical practice that is commonly practiced irrespective of religion or economic status is female genital mutilation. Nearly four out of five Ethiopian women are circumcised. There are three levels of circumcision that involve different degrees of cutting the clitoris and vaginal area. Many of these practices are done with an unsanitary blade with little or no anesthetics. It can result in heavy bleeding, high pain, and sometimes death.[36]

It was not until Christian missionaries traveled to Ethiopia bringing new religious beliefs and education that modern medicine was infused into Ethiopian medicine. Today there are three medical schools in Ethiopia that began training students in 1965 two of which are linked to Addis Ababa University. There is only one psychiatric treatment facility in the whole country because Ethiopian culture is resistant to psychiatric treatment. Although there have been huge leaps and bounds in medical technology there is still a large problem in the distribution of medicine and doctors in Ethiopia.[35]

See also

References

- ↑ Good Health at Low Cost. 25 years on: What Makes A Successful Health System? Balabanova et al, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, 2011

- ↑ Healthcare in Ethiopia, http://www.moh.gov.et/; http://www.ethiomedic.com/

- ↑ http://WWW.gapminder.org/tools/

- ↑ FMOH Health adiminstrative report

- ↑ Health Sector Development Plan; http://www.ethiomedic.com/

- ↑ "WHO - Global tuberculosis report 2016". www.who.int/tb/publication//global_report. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ↑ https://www.readbyqxmd.com/read/24903931/the-first-population-based-national-tuberculosis-prevalence-survey-in-ethiopia-2010-2011%7C The first population-based national tuberculosis prevalence survey in Ethiopia, 2010-2011|

- ↑ Health Extension Programme: An Innovative Solution to Public Health Challenges of Ethiopia. A Case Study, USAID.

- ↑ BRIEFING NOTE 2016, Unicef, Ethiopia Country Office

- ↑ The Health Extension Programme in Ethiopia. The World Bank, Washington DC, January 2013.

- ↑ EVALUATION OF HEP: Implementation process and effect on health outcomes VOLUME IV: SUPPORT AND MANAGEMENT OF HEP, RURAL ETHIOPIA, 2010

- 1 2 Second Generation Health Extension Programme, FMOH

- ↑ FMOH Organizational structure

- ↑ HSTP, 2015

- ↑ HSTP of ethiopia FMOH

- ↑ National Human resource for health strategic plan for Ethiopia 2016-2025

- ↑ Health Sector Transformation Plan

- ↑ http://www.emacpd.org/sites/default/files/resource_center/CPD_Accreditation_Guide_Final_March_20131.pdf

- ↑ Health Sector Transformation Plan,2015

- 1 2 http://www.moh.gov.et

- 1 2 Health and Health Related Indicator, EFY 2007

- ↑ Ethiopian Health and Health related Indicators, http://www.ethiomedic.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&id=65:health-and-health-related-indicators-for-ethiopia&Itemid=41&layout=default

- 1 2 3 Ethiopia country profile. Library of Congress Federal Research Division (April 2005). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ Yayehyirad Kitaw, Yemane Ye-Ebiyo, Amir Said, Hailay Desta, and Awash Teklehaimanot, "Assessment of the Training of the First Intake of Health Extension Workers", The Ethiopian Journal of Health Development, 21 (2007), pp. 232 - 239 (accessed 15 June 2009)

- ↑ BBC, The World Today, 24 July 2007

- ↑ "Global distribution of health workers in WHO Member States" (PDF). The World Health Report 2006. World Health Organization. Retrieved 2008-02-02.

- ↑ "Title" (PDF). www.etharc.org.

- ↑ "Ethiopia - Health and Welfare". countrystudies.us.

- ↑ WHO Country factsheet who.int Ethiopia factsheet 2012

- ↑ Macro International Inc. "2008. Ethiopia Atlas of Key Demographic and Health Indicators, 2005." (Calverton: Macro International, 2008), p. 13 (accessed 28 January 2009)

- ↑ Courtright, Paul, Lewallen, Susan, Chana, Harjinder, Kamjaloti, Steve and Chirambo, Moses, Collaboration with African Traditional Healers for the Prevention of Blindness. World Scientific Publishing Co. Pre. Ltd., Singapore (2000)

- ↑ Bodeker, Gerard: Planning for Cost-effective Traditional Health Services. International Symposium on Traditional Medicine. 11–13 September 2000.

- ↑ Kloos, H: The Geography of Pharmacies, Druggist Shops and Rural Medicine Vendors and the Origin of Customers of such Facilities in Addis Ababa. Journal of Ethiopian Studies 12: 77-94 (1974).

- ↑ Pankhurst, Richard: A Historical Examination of Traditional Ethiopian Medicine and Surgery, In: An Introduction of Health and Health Education in Ethiopia. E. Fuller Torry (Ed.). Berhanena Selam Printing Press, Addis Ababa (1996).

- 1 2 Giel, R., Gezahegn, Yoseph and Van Luijk, J. N; Faith Healing and Spirit Possession in Ghion, Ethiopia. Social Science and Medicine, 2: 63-79 (1968).

- ↑ Pankhurst, Richard.: A Historical Examination of Traditional Ethiopian Medicine. Ethiopian Medical Journal, 3:157-172 (1965).

Further reading

- Richard Pankhurst, An Introduction to the Medical History of Ethiopia. Trenton: Red Sea Press, 1990. ISBN 0-932415-45-8