Hatfield College, Durham

| Hatfield College | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| University of Durham | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

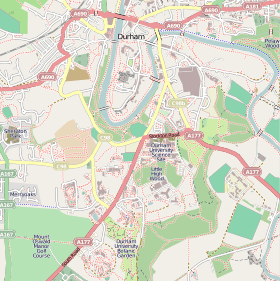

| Coordinates | 54°46′28″N 1°34′27″W / 54.7744°N 1.5741°WCoordinates: 54°46′28″N 1°34′27″W / 54.7744°N 1.5741°W | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Motto | Vel Primus Vel Cum Primis | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Motto in English | "Either the first or with the first" (colloquialised in College as "be the best you can be") | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Established | 1846 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Named for | Thomas Hatfield | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Master | Ann MacLarnon (2017-) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Undergraduates | 1010 (2017/18)[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Postgraduates | 260 (2017/18)[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Senior tutor | Anthony Bash | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Map | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Location in Durham, England | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Hatfield College is a college of Durham University in England. Founded in 1846 by David Melville,[2] it was the second college to be associated with the university, after University College (founded 1832). The college was originally called Bishop Hatfield's Hall, and is named after Thomas Hatfield, Prince-Bishop of Durham from 1345 to 1381. The college's founder pioneered the idea of catered residences for students which would later evolve to the now common practice of student residences.

Hatfield College occupies a large site above the River Wear on North Bailey and close to Durham Cathedral on the World Heritage Site peninsula. The buildings are an eclectic blend of 17th century halls, early Victorian buildings and major additions during the last century. The Jevons building, including the college bar and much ageing student accommodation, is being heavily renovated, with completion expected by the end of Epiphany term 2018.[3]

The current Master of the college is Ann MacLarnon, Professor of Evolutionary Anthropology at Durham University.[4] She replaced Tim Burt in September 2017.

History

The oldest part of the college site is what is today the dining room, which probably dates back to the 17th century.[5] In the 18th century the building became a coaching inn, The Red Lion - a stopping point for coaches travelling between London and Edinburgh. During this time it was also used to host concerts, likely featuring the work of composers like Charles Avison and John Garth.[6] In 1845 the Red Lion building was put up for sale, allowing it to become the first component of Hatfield College the following year.[7]

Hatfield College was established in 1846 as the second college of the university. The establishment of the college as a furnished and catered residence with fees set in advance was then a revolutionary idea, but later became general practice at student residences. This idea originated from the young founding Master, David Melville, who believed that the poor should be able to afford college residence and higher education. Three principles of the model were that rooms would be furnished and let out to students with shared servants, meals would be provided and eaten in the college hall, and college battels (bills) were set in advance.[8] This system made Hatfield a more economical choice when compared to University College, ensuring that student numbers at Hatfield built up steadily.[9] Melville's model was introduced to the wider university after an endorsement from the Royal Commission of 1862.[9] It was later introduced at Keble College, Oxford and eventually worldwide.

Although not established as a theological college, in the first 50 years the majority of college members were theology students and staff. Senior staff members and the Principal (who was always a clergyman until 1897) were clerics. Student numbers rose to over 100, and in the 1890s the college purchased Bailey House and the Rectory to accommodate its students.[10] As the end of the century drew closer the balance of undergraduate students rapidly shifted away from theology. In 1900, there were 49 arts students who had matriculated within the previous 3 years, and 20 in theology.[11] By 1904 just 9 theology undergraduates are recorded, compared to 57 in arts.[11]

Inter-war

The inter-war period saw a decline in college fortunes. In the first two decades of the 20th century Hatfield experienced a sharp fall in numbers. This was caused initially by the decision to isolate science courses at the campus in Newcastle, an increased tendency to train priests at specialised colleges, poor finances, and finally the outbreak of the First World War.[12] For 15 years after 1897, total students in residence numbered above 100.[12] This had fallen to 69 in 1916, 2 in 1917, and to 3 in 1918.[12] After the war finished there was a temporary leap to more than 60 undergraduates, but by 1923 there were just 14 men on the college books.[12] In 1924 a new science department was established in Durham, and this, along with the active recruiting efforts of new Master Arthur Robinson, saw a steady increase in student numbers.[13] Within five years of Robinson's appointment they had quintupled from the low of 1923.[13]

In spite of this improvement the economic crisis of the 1920s led to uncertainty for Hatfield: it had more students than University College but lacked the facilities, especially kitchens, to accommodate them. University College, meanwhile, faced the deterioration of its buildings and low student numbers. To address this, the two colleges amalgamated under the guidance of Angus Macfarlane-Grieve, and all meals were taken together in the Great Hall of University College.[10] Unhappy with the amalgamation, some Hatfielders underlined their separate identity in trivial ways: for example, insisting on using a different door to enter the Castle dining hall than the University College students, and, in contrast to the University College contingent - turning to face the High Table during grace.[14]

Post-war

After the war, 20 years of co-operation with University College came to an end, and Hatfield students could finally return to their college. By now Hatfield was again faced with accommodating an increased number of students, as the war had created a growing backlog. More buildings were constructed and refurbished. The Pace building, described by Pevsner as 'friendly', with a 'nice rhythm of windows towards the river', was finished in 1950.[15] Kitchen Block and Gatehouse Block followed in 1955 and 1962 respectively. Dunham Court was completed with the development of the modernist style Jevons building - named after Frank Jevons, the first lay Master of the college.[16] Moreover, accommodation was acquired away from the main site and the Senior Common Room was established. In 1962 it was decided that a brass plaque should be fixed to the college gates identifying the establishment as Hatfield College.[17] Just 24 hours after installation a group of students from a rival Bailey college were caught trying to remove the plaque as a sporting trophy.[18]

In 1963 the college received its first taste of student protest, when a 'militant minority group of young gentlemen united under the banner of International Socialism'.[19] Around the same time students voted to boycott formal dinners after a row with the Master over whether or not jeans counted as formal wear.[20] Reforms were subsequently introduced. Joint standing committees, composed equally of staff and students, were set up to 'deliberate almost every conceivable topic' and the undergraduate Senior Man was allowed to take part in meetings of the College's Governing Body.[19] By 1971 a 'liberal and balanced' Governing Body had been achieved: consisting of 4 college tutors, 4 elected tutors, 4 delegates from the Junior Common Room, and a representative from the Hatfield Association alumni group.[21] Writing in the same year, then Master Thomas Whitworth was able to boast of warding off the 'mischievous opportunism' of student 'exhibitionists'.[22]

Modern

The leadership of James Barber (1980-1996) was a period of significant change. Student numbers rose significantly, increasing to over 650 by the time he finished his tenure in office.[10] Living out became compulsory for students for at least part of their career, and many of the existing buildings were either rebuilt or refurbished to make room for students: The Rectory was remodeled, C & D Stairs were refurbished, the Main Hall was repaired, and Jevons' was redecorated.[10] A Middle Common Room for the postgraduate community was added in Kitchen Stairs. In 1981, it was decided the Formal Ball would be renamed 'The Lion in Winter', which it has been called ever since.[23] More comically, 'C Scales', a goldfish, was elected as a member of the JCR in 1982 and put forward as a potential Durham Student Union President.[23] In 1984, the JCR was sued by representatives of the band Mud after a student ruined four speakers by pouring beer into an amplifier during a performance at a college ball.[24]

Hatfield also became co-educational, which at the time was only 'grudgingly accepted' by the college.[10] In 1985 talk of going mixed was stimulated by the low numbers of applicants selecting Hatfield as their preference, and a recent decline in academic standards - with the college finishing bottom of the results table the previous year.[25] Despite threats of hooliganism, the Senior Common Room decided in May of that year to push forward with plans to go mixed.[26] In March 1987 a student referendum was held on the issue, with 79.2% voting for the college to remain men only.[27] The Senate decided that, despite the referendum result, the college would in fact go mixed the following year.[27] The first female Senior Man held the post in 1992.[10] Her election win, by a single vote, prompted some students to declare a week of mourning and walk around the college wearing black arm bands.[27]

Chapel

The college chapel was conceived in 1851 and built by 1854, funded by donations by alumni and a loan of £150 from the university.[10] It was designed by then chaplain to Bishop Cosin's Hall, James Turner (also a trained architect), and contains two head sculptures of William Van Mildert and Warden Thorp. Decorative furnishings were later added and the first organ was installed in 1882. Commemorative wooden panels marking the First World War dead and a book of remembrance for them, along with a lectern, were added gradually and were primarily funded by alumni and the Hatfield Association. The chapel houses a Harrison & Harrison organ, which is used to accompany services and for recitals. In 2001 it was refurbished at the cost of £65,000.[10]

Attendance at chapel services was compulsory for 80 years after the foundation of the chapel until the onset of World War II ended the compulsory attendance to Cathedral services. Since then the chapel constitutes an 'important but minority interest' in the college.[10]

Services are led by the college chaplain, currently Anthony Bash. The College Chapel Choir is led by a student choral director, supported by an organ scholar and deputy organ scholar. The Chapel Choir consists mainly of students who support regular worship in the chapel, but also sing at churches and cathedrals throughout the country and undertake annual tours both at home and abroad.[28]

College traditions

Arms

The original arms used by the college consisted of the shield of Thomas Hatfield turned into a circular device with the motto “Vel Primus, Vel Cum Primis”. The use of these arms was, however, found to be illegal as they were not registered with the College of Arms.[29][30] As the arms had been used for over 100 years the college was able to retain the shield, although it had to be differentiated from that of Hatfield by the addition of an ermine border. The current coat of arms features the Shield of Hatfield and is blazoned as "Azure a Chevron Or between three Lions rampant Argent a Bordure Ermine", with the college motto underneath: "Vel Primus Vel cum Primis" which literally means "Either First or With the First"[31] although it is now misinterpreted by the college as "Be the Best you can Be".[32]

Academic dress

Similar to most Bailey Colleges the wearing of the undergraduate academic gown is required to formal events. The wearing of the gown is at the discretion of the Master of the college and at present is worn at Matriculation, in chapel and at formal meals held in the hall twice per week.

Grace

Benedicte Deus, qui pascis nos a iuventute nostra et praebes cibum omni carni, reple gaudio et laetitia corda nostra, ut nos, quod satis est habentes, abundemus in omne opus bonum. Per Jesum Christum, Dominum Nostrum, cui tecum et Spiritu Sancto, sit omnis honor, laus et imperium in saecula saeculorum. Amen.

This can be translated as: Blessed God, who feedest us from our youth, and providest food for all flesh, fill our hearts with joy and gladness, that we, having enough to satisfy us, may abound in every good work, through Jesus Christ our Lord, to whom with thee and the Holy Spirit, be all honour and praise and power for all ages. Amen.

The grace was widely used in the fourth century and is based on earlier Hebrew prayers. It was translated from the Greek and adopted by Oriel College, Oxford. Presumably influenced by Henry Jenkyns, who was a Fellow of Oriel, Hatfield adopted this grace practically verbatim. Since 1846 the grace has been read at all formal meals in College which occur once a week, or twice in Michaelmas Term.

Student body

As of the 2017/18 academic year, Hatfield College has a population of 1,339 students.[1] There are 1,007 full-time undergraduates and 3 part-time undergraduates.[1] Postgraduate figures include 55 students on full-time postgraduate research programs and 111 studying for full-time postgraduate taught programs, plus a further 94 part-time postgraduate students (research and taught) as well as 69 distance learning students.[1] Student numbers have grown significantly since the 2003/04 academic year, when the college comprised a total of 779 students.[33]

Formals

Formals take place twice a week on a Tuesday and Friday in Michaelmas Term, reducing to Fridays only for the rest of the academic year. There are a number of traditions at Formals. Students are required to wear their full academic dress including gowns for formal dinners except when it is a black or white tie event. A High Table consisting of members of the SCR and guests is present at every formal, with the Master's entrance and "bowing out" signifying the official opening and closing of the formal meal.

Unique to Hatfield is the tradition of 'spooning', in which students bang spoons on the edge of the table or on silverware for several minutes before the formal starts.[34] The act immediately ceases when the High Table walks in.[34]

Common Rooms

The student body is divided into three "common rooms". The Junior Common Room (JCR) is for undergraduates in the college. The JCR annually elects an Executive Committee consisting of ten members including an impartial Chair. The Executive Committee ensures the successful running of the JCR, in conjunction with the College Officers.[35] Unlike other colleges, Hatfield exclusively retains "Senior Man" as its title for the head of the JCR, having rejected a motion to move to "JCR President" in May 2014[36] and a motion to allow the incumbent to choose between "Senior Man", "Senior Woman" or "Senior Student" in January 2016.[37]

The Middle Common Room (MCR) is the organisation for Postgraduate students which also have an elected organising committee. Postgraduate accommodation is located at James Barber House.[38] College Officers, fellows and tutors are members of the Senior Common Room (SCR).[39] Each Common Room acts as a separate body for its members, although collaboration between them is common, and it is possible to be a member of these organisations simultaneously.

Admissions

Hatfield tends to be one of the more popular colleges for applications. For the 2015/2016 entry cycle 1,375 applicants selected the college as their preference.[40] This made it the 5th most popular overall, behind University College, Josephine Butler College, Collingwood College, and St Mary's College.[40] 336 accepted applicants ultimately enrolled.[41] Compared to most other colleges, Hatfield receives a somewhat higher percentage of gap year applicants who choose to defer entry, with 7.8% of applicants in the 2015/2016 cycle choosing to defer, against a university average of 3.8%.[40] Figures for the two previous admissions cycles were 6.3%[42] and 6.4%[43] respectively. Overall, figures for 2016 entry show that of all offer-holding applicants who selected Hatfield as their college preference, 78% were successful in gaining a place at the college.[44]

On campus the college has a longstanding reputation for being 'rah',[45][46] with one mocking student article calling it a 'moneyed, upper-class college equivalent of Millwall FC' and holding Hatfield responsible for perpetuating negative stereotypes about the wider university.[47] Admissions statistics do show it to be disproportionately popular with applicants from independent schools, typically enrolling a significantly higher percentage than other colleges. For the 2015/2016 cycle, 65.8% of applicants were privately educated - against a university total of 36.1%[48] - with 34.2% applying to Hatfield from state schools.[48] By comparison, the College of St Hild and St Bede was the second most popular with independent school applicants at 54.5%, with all other colleges receiving less than half of their applications from independent schools.[48] Hatfield's total represents a slight decrease from the previous application cycle, in which 67.6% of applicants were from independent schools.[49]

College officers and fellows

Master

The current master is Ann MacLarnon, having assumed the role in September 2017.

List of past Masters

- David Melville (1846–1851)

- William Henderson (1851–1852)

- Edward Bradby (Michaelmas Term 1852)

- James Lonsdale (1853–1854)

- John Pedder (1854–1859)

- James Barmby (1859–1876)

- William Sanday (1876–1883)

- Archibald Robertson (1883–1897)

- Frank Jevons (1896–1923)[50]

- Arthur Robinson (1923–1940)[51]

- Angus Macfarlane-Grieve (1940–1949) as acting Master[52]

- Eric Birley (1949–1956)[53]

- Thomas Whitworth (1957–1979)[54]

- James Barber (1980–1996)[55]

- Tim Burt (1996–2017)

Fellows

Hatfield College Council awards honorary fellowships on the advice of the Master to alumni and people who have a close association with Hatfield. On receipt of the fellowship the fellow automatically becomes an honorary member of the SCR and receives the same benefits. As of 2012, honorary fellows numbered 24 in total, notably including former university Chancellor Bill Bryson.[56]

Other staff affiliated to the college include 8 Junior Research Fellows[57] and 10 Senior Research Fellows.[58] Current Senior Fellows include, amongst others, Douglas Davies and Geoffrey Scarre.[59] The college also occasionally hosts visiting academics, normally for one term, as part of the fellowship scheme offered by the University's Institute of Advanced Study.[60] Brian Belcher[61] and William Forde Thompson[62] are recent IAS fellows connected to Hatfield.

Sports and societies

Hatfield College Boat Club

| Hatfield College Boat Club | |

|---|---|

_Boat_Club_Blade.svg.png) | |

| Location | Hatfield College Boathouse |

| Home water | River Wear |

| Founded | 1846 |

| Affiliations | |

| Website |

www |

Hatfield College Boat Club (HCBC) is the boat club of Hatfield College at Durham University. The club was started in 1846, shortly after the founding of the college, making it one of the oldest student clubs in Durham.[63] There is a Novice Development programme for absolute beginners.[64] It also trains coxes and has a dedicated Coxes Captain.[64]

Notable former members of the club include Alice Freeman, Louisa Reeve, and Simon Barr.

Other sports and societies

Hatfield College participates in most sports in the university and has become known for prowess in rugby in particular, with the college coming to be regarded as a nursery for British rugby - so much so that Dr Thomas Whitworth (Master, 1957-79), a known rugby enthusiast, was often accused of bias in the selection and treatment of rugby-playing students.[10] In intercollegiate rugby Hatfield become the dominant club in the decades following the war, with Hatfield conceding the colleges cup just once in a 14 year period up to 1971.[65] Marcus Rose, Will Carling, and Will Greenwood are the most notable former undergraduates. Jeremy Campbell-Lamerton, Andy Mullins, and Ben Woods also went on to make international appearances.

In cricket, Andrew Strauss, winning captain during the 2009 Ashes, former Worcestershire captain Tim Curtis, and fast bowler Typhoon Tyson, the Wisden Leading Cricketer in the World for 1955, were all students of the college.

Hatfield also has its own theatre group, the Lion Theatre Company, which performs in Durham University's Assembly Rooms theatre located opposite the college gates, and a music society organising various ensembles. Students also produce the termly college magazine, The Hatfielder. It has SHAPED, which is a personal development program.[66]

Notable alumni

Hatfield alumni are active through organisations and events, such as the Hatfield association, which now has a membership of more than 4,000 graduates.[67] A number of Hatfield alumni have made significant contributions in the fields of government, law, science, academia, business, arts, journalism, and athletics, among others.

.jpg) Sir Tim Smit, founder of the Eden Project

Sir Tim Smit, founder of the Eden Project Jeremy Vine, presenter, broadcaster and journalist for the BBC

Jeremy Vine, presenter, broadcaster and journalist for the BBC

Andrew Strauss, English international cricketer

Andrew Strauss, English international cricketer.jpg) Richard Dannatt, retired senior British Army officer and former Constable of the Tower of London

Richard Dannatt, retired senior British Army officer and former Constable of the Tower of London Will Greenwood, English rugby player and winner of the 2003 World Cup

Will Greenwood, English rugby player and winner of the 2003 World Cup Kim Darroch, Diplomat, currently British Ambassador to the United States

Kim Darroch, Diplomat, currently British Ambassador to the United States

| Name | Degree (Graduated) | Career | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cliff Addison | Professor of Inorganic Chemistry, University of Nottingham (1960–78), Dean of Faculty of Pure Science (1968–71), Leverhulme Emeritus Fellow, 1978 | [68] | |

| Oliver Balch | BA History (1998) | Author and freelance writer | [69] |

| Warren Bradley | Manchester United F.C. and England footballer | [70] | |

| Robert Buckland | Law (1990) | Conservative Party Member of Parliament for Swindon South and HM Solicitor General for England & Wales | [71] |

| Gordon Cameron | BA | Professor of Land Economy, Cambridge University, and Master at Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge, from 1988 | [72] |

| Will Carling | BSc Psychology (1986) | Rugby union player for Harlequin F.C., former captain of the England national rugby union team (1988-1996) | [73] |

| Dominic Carman | Journalist and Liberal Democrat politician | [74] | |

| Patrick Carter, Baron Carter of Coles | BA Economics (1967) | Chairman, Sport England (2002–06) | [75] |

| Tim Curtis | BA English Language and Literature (1983) | England cricketer | [73] |

| Richard Dannatt, Baron Dannatt | BA Economic History (1976) | Former Chief of General Staff, British Army | [76][77] |

| Kim Darroch | BSc Zoology (1975) | British diplomat, Ambassador to the United States | [78] |

| Kingsley Dunham | PhD Geology (1932) | Geologist and mineralogist, Senior Fellow of Hatfield College (1990) | [79] |

| Katharine Ford | BA Sport (2010) | Ultra Cyclist, 4 time UMCA (WUCA) World Record holder, the first Scottish cyclist to officially finish Race Across America and first Briton to successfully attempt 12 Hours Solo riding on an Indoor Velodrome | [80] |

| Nigel Glover | PhD Physics (1985) | Professor of Physics, Durham University | [81] |

| Will Greenwood | BA Economics (1994) | England rugby union player and a member of the 2003 Rugby World Cup winning squad | [82] |

| Alastair Haggart | LTh (1941); BA (1942) | Bishop of Edinburgh in 1975-85 | [83] |

| Temple Hamlyn | LTh 1889; Hon. MA 1902; DD 1904 | Bishop of Accra (1908 – 1910) | [84] |

| Clive Handford | BA, DipTh | Bishop in Cyprus and the Gulf (1996–2007), President Bishop, Episcopal Church in Jerusalem and the Middle East, 2002–07; an Assistant Bishop, Diocese of Ripon and Leeds, since 2007 | [85] |

| Ralph Hawkins | BA (1934) | Bishop of Bunbury from 1957 to 1977 | [86] |

| Sidney Holgate | BA Math (1940), DThPT (1941), MA (1943), PhD (1945) | [87] | |

| Joanne Johnson | BSc Geology (1998) | Scientist British Antarctic Survey (2002-Present) | [88] |

| Donald Knowles | BA Theology | Bishop of Antigua (1953 – 1969) | [89] |

| Harold Orton | BA (1921) | Professor of English Language and Medieval English Literature, University of Leeds (1946–64) | [90] |

| Richard Pease | BA General Studies (1980) | Fund Manager, Crux Asset Management | [91] |

| Peter Grant Peterkin | BA History (1970) | Army Officer, House of Commons Serjeant at Arms (2004-2007) | [92] |

| Tracy Philipps | BA (1912) | Intelligence Officer (1914-18) and Colonial Administrator (1923-35) | [93] |

| Mark Pougatch | BA Politics (1990) | Radio presenter, journalist and author | [94] |

| Louisa Reeve | British rower | [29] | |

| Marcus Rose | BA Sociology (1979) | England rugby union international full back | [73] |

| David Shukman | BA Geography (1980) | Environment & Science correspondent for BBC News | [74] |

| Tim Smit | BA Archaeology and Anthropology (1976) | Businessman and archaeologist famous for his work on the Eden Project and the Lost Gardens of Heligan | [74] |

| Andrew Strauss | BA Economics (1998) | Former England Test cricket team captain | [95] |

| Jake Thackray | BA Modern Languages | Musician | [74] |

| Frank Tyson | BA English Literature | England cricketer, later journalist and commentator | [73] |

| Jeremy Vine | BA English (1986) | Author, journalist and news presenter for the BBC | [74] |

| Dave Walder | Rugby union footballer who plays at fly-half for Mitsubishi Sagamihara DynaBoars in Japan | [29] | |

| Ben Woods | Former rugby union player who played for Newcastle Falcons and Leicester Tigers as an openside flanker | [29] | |

| Ted Wragg | BA German (1960) | Educationalist and academic, Professor of Education at the University of Exeter (1978-2003) | [74] |

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Term-Time Accommodation Stats" (PDF). Student Registry. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- ↑ Dimbleby, Josceline (2005). A Profound Secret. London: Transworld Publishers. pp. 33–35. ISBN 9780552999816.

- ↑ "Hatfield College : Accommodation - Durham University". www.dur.ac.uk. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ↑ "Hatfield College : Who's Who - Durham University". www.dur.ac.uk. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ↑ "Hatfield College". Durham World Heritage Site. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ "Hatfield Record - 2009". Issuu. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ "Hatfield College". Durham World Heritage Site. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ "Hatfield College History: Introduction". Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- 1 2 "Hatfield College History". community.dur.ac.uk. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "College History Summary" (PDF). Hatfield College. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- 1 2 Moyes, Arthur (1996). Hatfield 1846 - 1996. p. 93.

- 1 2 3 4 Whitworth, Thomas (1971). Yellow Sandstone and Mellow Brick. p. 28.

- 1 2 Whitworth, Thomas (1971). Yellow Sandstone and Mellow Brick. p. 33.

- ↑ Whitworth, Thomas (1971). Yellow Sandstone and Mellow Brick. p. 34.

- ↑ "Hatfield College History: Buildings". Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ↑ "Hatfield College History: Principals & Masters". Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ↑ Whitworth, Thomas (1971). Yellow Sandstone and Mellow Brick. p. 46.

- ↑ Whitworth, Thomas (1971). Yellow Sandstone and Mellow Brick. p. 47.

- 1 2 Whitworth, Thomas (1971). Yellow Sandstone and Mellow Brick. p. 51.

- ↑ "Background to the Hatfield Affair". Palatinate (182). 23 May 1964. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- ↑ Whitworth, Thomas (1971). Yellow Sandstone and Mellow Brick. p. 52.

- ↑ Whitworth, Thomas (1971). Yellow Sandstone and Mellow Brick. p. 53.

- 1 2 Moyes, Arthur (1996). Hatfield 1846-1996. p. 324.

- ↑ "oh Hatfield..." Palatinate (379): 8. 10 October 1984. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ↑ "Hatfield All Mixed Up". Palatinate (385): 8. 14 February 1985. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- ↑ "Hatfield For Girls". Palatinate (388): 388. 9 May 1985. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- 1 2 3 Moyes, Arthur (1996). Hatfield 1846-1996. p. 306.

- ↑ "Hatfield College Chapel Choir". Archived from the original on 2012-04-02. Retrieved 2011-09-12.

- 1 2 3 4 "Web site History of Hatfield" (PDF).

- ↑ "Hatfield College - Durham University". www.dur.ac.uk.

- ↑ "Hatfield College : Crest & Motto". www.dur.ac.uk. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ "Hatfield College - Durham University". www.dur.ac.uk.

- ↑ "Term-Time Accommodation Stats" (PDF). Student Registry. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- 1 2 "Hatfield College @ Durham SU". www.durhamsu.com. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ Hatfield College JCR Archived 2012-11-06 at the Wayback Machine. undergraduate student organisation, URL accessed 19 December 2009

- ↑ "Hatfield JCR crush motion to rename Senior Man". Durham University. 15 May 2014. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ↑ "Hatfield College JCR rejects motion to change JCR President title to 'Senior Student' | Palatinate Online". Palatinate Online. 24 January 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ↑ "Hatfield MCR - James Barber House". community.dur.ac.uk. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ Hatfield College SCR staff organisation, URL accessed 19 December 2009

- 1 2 3 "College Preference - Total Applications" (PDF). Durham University. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ "College Entrants - Total Entrants" (PDF). Durham University. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ "College Preference - Total Applications" (PDF). Durham University. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ "College Preference - Total Applications" (PDF). Durham University. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ "College Preference Statistics" (PDF). Durham University Collegiate Office. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- ↑ "These are officially the most private school Durham colleges". The Tab Durham. 28 February 2018. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ "The Palatine Jungle: Part 1 | Durham21". www.durham21.co.uk. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ "Durham's worst colleges". The Tab Durham. 7 November 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- 1 2 3 "College Preference by School Type" (PDF). Durham University. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ "College Preference by School Type" (PDF). Durham University. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ "Jevons, Frank Byron, (9 Sept. 1858–29 Feb. 1936)". Who Was Who. Oxford University Press. 1 December 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ "Robinson, Arthur, (10 March 1864–21 March 1948)". Who Was Who. Oxford University Press. 1 December 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ "Macfarlane-Grieve, Angus Alexander, (11 May 1891–2 Aug. 1970)". Who Was Who. Oxford University Press. 1 December 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ "Birley, Prof. Eric, (12 Jan. 1906–20 Oct. 1995)". Who Was Who. Oxford University Press. 1 December 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ "Whitworth, Thomas, (7 April 1917–18 Dec. 1979)". Who Was Who. Oxford University Press. 1 December 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ "Barber, Prof. James Peden, (6 Nov. 1931–24 July 2015)". Who Was Who. Oxford University Press. 1 December 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ "Hatfield Record 2012" (PDF). Hatfield Association. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- ↑ "Hatfield College : Junior Research Fellows - Durham University". www.dur.ac.uk. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ↑ "Hatfield College : Senior Research Fellows - Durham University". www.dur.ac.uk. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ↑ "Hatfield College : Senior Research Fellows - Durham University". www.dur.ac.uk. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- ↑ "Institute of Advanced Study : IAS Fellows - Durham University". www.dur.ac.uk. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- ↑ "Institute of Advanced Study : Professor Brian Belcher - Durham University". www.dur.ac.uk. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- ↑ "Institute of Advanced Study : Professor William Thompson - Durham University". www.dur.ac.uk. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- ↑ "Finding the Balance Hatfield College JCR". Hatfield JCR. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- 1 2 "Finding the Balance". Hatfield JCR. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- ↑ Whitworth, Thomas (1971). Yellow Sandstone and Mellow Brick. p. 85.

- ↑ "Home". Hatfield SHAPED.

- ↑ "Hatfield College : Hatfield Association". Durham University. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ "Addison, Prof. Cyril Clifford, (28 Nov. 1913–1 April 1994)". Who Was Who. Oxford University Press. 1 December 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ "Hatfield College : Alumni - Durham University". Durham University. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ↑ Obituary, manutd.com, URL accessed May 18, 2009

- ↑ "Members of Parliament for Swindon". Newsquest Media Group. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ↑ "Cameron, Prof. Gordon Campbell, (28 Nov. 1937–14 March 1990)". Who Was Who. Oxford University Press. 1 December 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Sporting history Archived 2012-10-19 at the Wayback Machine., dur.ac.uk, URL accessed May 18, 2009

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 List of alumni, dur.ac.uk, URL accessed May 18, 2009

- ↑ "Carter of Coles, Baron, (Patrick Robert Carter) (born 9 Feb. 1946)". Who's Who. Oxford University Press. 1 December 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ Sir Richard Dannatt profile, mod.uk, URL accessed May 18, 2009

- ↑ College fellows, URL accessed May 18, 2009

- ↑ Darroch, Sir (Nigel) Kim. ukwhoswho.com. Who's Who (online edn, Nov 2015 ed.). A & C Black, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing plc. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ↑ "Dunham, Sir Kingsley (Charles), (2 Jan. 1910–5 April 2001)". Who Was Who. Oxford University Press. 1 December 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ "About Katie". Epilepsy Forward. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ Staff profile, University of Durham, retrieved 2016-02-28.

- ↑ "Allowing exceptional people to do exceptional things". Durham University. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ "Haggart, Rt Rev. Alastair Iain Macdonald, (10 Oct. 1915–11 Jan. 1998)". Who Was Who. Oxford University Press. 1 December 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ "Hamlyn, Rt Rev. N. Temple, (9 Nov. 1864–26 Jan. 1929)". Who Was Who. Oxford University Press. 1 December 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ "Handford, Rt Rev. (George) Clive, (born 17 April 1937)". Who's Who. Oxford University Press. 1 December 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ "Hawkins, Rt. Rev Ralph Gordon, (1911–1987)". Who Was Who. Oxford University Press. 1 December 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ "Holgate, Dr Sidney, (9 Sept. 1918–17 May 2003)". Who Was Who. Oxford University Press. 1 December 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ "Joanne Johnson". British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- ↑ "Knowles, Rt Rev. Donald Rowland, (14 July 1898–26 Sept. 1977)". Who Was Who. Oxford University Press. 1 December 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ "Orton, Prof. Harold, (1898–7 March 1975)". Who Was Who. Oxford University Press. 1 December 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ "Richard Pease | Fund Manager Fact Sheet | CRUX Asset Management". Citywire. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ↑ "Maj-Gen Peter Grant Peterkin, CB, OBE". People of Today Online. Debrett's. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- ↑ "Philipps, Tracy, (1890–21 July 1959)". Who Was Who. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- ↑ "Alumnus Mark Pougatch shares his thoughts on sports". Durham University. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ Andrew Strauss at British Universities and Colleges Sport, URL accessed May 18, 2009

Further reading

- T. A.Whitworth (1971). Yellow Sandstone and Mellow Brick. Hatfield.

- W.A. Moyes (1996). Hatfield 1846 – 1996. Hatfield Trust.

- W.A. Moyes (2004). Class of 1846. Hatfield Trust.

- Hatfield Students (1945–1947). The Hatfield Magazine. Hatfield.

- Hatfield Association (1947). The Hatfield Record.

External links

- Hatfield College official website

- Hatfield College JCR undergraduate student organisation

- Hatfield College MCR postgraduate student organisation

- Hatfield College SCR staff organisation

- Hatfield History a brief interactive history of Hatfield College

- Hatfield College Boat Club (HCBC)

- Photos of Hatfield, collegiateway.org