Haccombe

Haccombe is a hamlet, former parish and historic manor in Devon, situated 2 1/2 miles east of Newton Abbot, in the south of the county. It is possibly the smallest parish in England, and was said in 1810 to be remarkable for containing only two inhabited houses, namely the manor house known as Haccombe House and the parsonage.[1] Haccombe House is a "nondescript Georgian structure" (Pevsner), rebuilt shortly before 1795[2] by the Carew family on the site of an important mediaeval manor house.[3]

Next to the house is the small parish church dedicated to Saint Blaise, remarkable not only for the many ancient stone sculpted effigies and monumental brasses it contains,[4] amongst the best in Devon,[3] but also because the incumbent has the rare title of Archpriest and is accountable not to the local bishop (Bishop of Exeter), as are all other parish churches in Devon, but to the Archbishop of Canterbury. The archpresbytery was established in 1341 with six clergy; only the archpriest survived at the Reformation.[5] The ecclesiastical parish is now combined with that of Stoke-in-Teignhead with Combe-in-Teignhead. Haccombe with Combe is a civil parish in the Teignbridge local government district.

The manor was the seat of important branches of the Courtenay and Carew families.

Descent of the manor

The descent of the manor of Haccombe was as follows:

de Haccombe

The earliest recorded holder of the manor was the de Haccombe family,[7] which as was usual took its surname from the manor.

- Stephen de Haccombe, who is recorded as holding the manor in 1242.[8]

- Sir Jordan de Haccombe, successor[8]

- Sir Stephen de Haccombe, successor[8]

- Jordan de Haccombe, successor, who married the daughter and heiress of Mauger de St Awbin, but left no sons, only a daughter and sole-heiress Cecily de Haccombe, wife of Sir John Archdekne, to whom passed the manor.[8]

Archdekne

- Sir John Archdekne, who married Cecily de Haccombe, heiress of Haccombe,[8] by whom he had in the words of Tristram Risdon (died 1640) "A fruitful progeny especially of issue male".[10] However, of his nine sons only two left children, namely Sir Warren Archdekne, second son and eventual heir; and the third son Richard Archdekne whose son Richard Archdekne died childless.[10]

- Sir Warren Archdekne, second son and heir,[11] who married Elizabeth Talbot, a co-heiress of John Talbot. He left no sons, only four daughters and co-heiresses,[12] including Phillipa Archdekne, eventual heiress of Haccombe, the second wife of Sir Hugh Courtenay (c. 1358–1425).

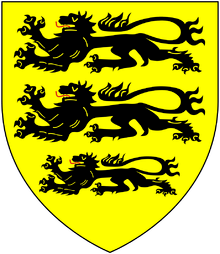

Courtenay

- Sir Hugh Courtenay (c. 1358–1425), of Haccombe and of Boconnoc in Cornwall, who married as his second wife Phillipa Archdekne, heiress of Haccombe. He was a Member of Parliament and Sheriff of Devon, a grandson of Hugh de Courtenay, 2nd/10th Earl of Devon (1303–1377), was the younger brother of Edward de Courtenay, 3rd/11th Earl of Devon (1357–1419), "The Blind Earl", and by his third wife was the grandfather of Edward Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon (died 1509), KG, created Earl of Devon in 1485 by King Henry VII.

His marriage to Phillipa Archdekne was without male children, but did produce a daughter Joane Courtenay (born 1411), the wife of Nicholas Carew of Mohuns Ottery in Devon, and the eventual sole-heiress of her mother Phillipa Archdekne, from whom she inherited 16 manors including Haccombe, which she divided amongst her younger Carew sons.[10]

Carew

Nicholas Carew

Nicholas Carew of Mohuns Ottery in Devon, who married Joane Courtenay (born 1411), a daughter of Sir Hugh Courtenay (1358–1425) of Haccombe and of Boconnoc.[14] As her eldest son was already well provided for as the heir to his father's estates of Mohuns Ottery and others under primogeniture, Joane Courtenay gave Haccombe to her second son Nicholas Carew, as was common practice in such situations,[lower-alpha 1] who founded there a prominent junior branch of the Carew family. (See Carew baronets (1661) of Haccombe).[15] Risdon however states the reason for Joan Courtenay having passed over her eldest son in distributing the Haccombe estates was "for some defect of a due respect to his mother (as she conceived)".[10]

The Carew family of Haccombe obtained a baronetcy in 1661, still extant today, and continued to reside at that estate until the 19th century,[16] having earlier inherited further estates from other advantageous marriages, including Bickleigh, inherited by Sir Thomas Carew, 1st Baronet (died 1673/4) following his first marriage to Elizabeth Carew, eldest daughter and co-heiress of Sir Henry Carew of Bickleigh[17] and Tiverton Castle, the ancient seat of the Courtenay Earls of Devon, which latter was inherited by Sir Thomas Carew, 4th Baronet of Haccombe from his marriage to Dorothy West, a daughter and co-heiress of Peter West of Tiverton Castle.[18]

Joan Courtenay survived her husband and married secondly, by royal licence dated 5 October 1450, Sir Robert Vere, second son of Richard de Vere, 11th Earl of Oxford, by whom she had a son, John Vere,[19] father of John de Vere, 15th Earl of Oxford.

Nicholas Carew (died 1469)

Nicholas Carew (died 1469), second son, who was given Haccombe by his mother Joan Courtenay. He married Anna[20] Crocker, "widow of John Seymour"[21] and a daughter of Sir John[22] Crocker (died 1508) of Lyneham in the parish of Yealmpton, Devon, a Member of Parliament for Devon in 1491,[23] whose inscribed monumental brass, showing him dressed in armour, survives in Yealmpton Church.

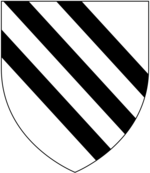

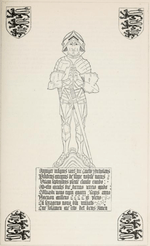

The well-known and fine small monumental brass of Nicholas Carew, "in spiky armour", between four heraldic escutcheons displaying the arms of Carew, survives set into a ledger stone on the floor of the chancel of Haccombe Church, on the south side of the effigy of Sir Stephen de Haccombe. It was described as follows by Stabb (died 1917): "The armour is very rich; on his head is a visored salade raised to show the face; on the shoulder are paldrons, and on the right shoulder a peculiarly shaped plate of steel, called a moton; the hands, which wear gauntlets, are joined in prayer; the elbow and knee plates are large. The sword, which hangs in front, is long and reaches to the feet, the latter having spurs on the heels".[24] Beneath the figure is the following leonine verse inscription in Latin:[25]

- Armiger insignis jacet hic Carew Nicholaus,

- Prudens egregius de stirpe nobili natus,

- Vitam Septembris p(rae)sente(m) clausit eundo,

- Ab isto mensis die decimo tercio mu(n)do,

- Edwardi nono regni quarti ratis anno,

- Necnon millen(sim)o CCCCo[26] quae pleno,

- Cu(m) sexagen(sim)o nono d(omi)ni num(er)ato,

- Cui solamen a(n)i(ma)e cito det Deus Amen.

Which may be translated as follows:

"A distinguished esquire lies here: Nicholas Carew, outstandingly foreseeing, born of a noble stock. He closed this present life in going from this world on the thirteenth of September in the ninth year reckoned of the reign of Edward the fourth and indeed in the one thousandth four hundredth and sixty ninth numbered of our Lord,[27] a comfort to the soul of whom may God give in haste"

John Carew (d.1528)

John Carew (d.1528)[28] of Haccombe, son and heir, who was a commander in the army (called Exercitus Anglicorum et Gallorum Regnum pro Pontifice Romano Liberando Congregatus[29] "The army of the Kingdoms of the English and of the French gathered together for the liberating of the Roman Pope") sent into Italy in 1527 jointly by Kings Francis I of France and Henry VIII of England and under the command of Odet of Foix, Viscount of Lautrec,[30] in order to rescue Pope Clement VII, then besieged in his Castel Sant'Angelo,[31] following the Sack of Rome on 6 May 1527 by troops of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. On 6 June 1527 the siege was lifted and Clement VII surrendered to the imperial troops, having agreed to pay a large ransom. Carew died at Pavia in 1528,[32] soon after the pope's release. Carew married Katherine Zouch, a daughter of John la Zouche, 7th Baron Zouche, 8th Baron St Maur (1459–1526), who survived her husband and remarried to Sir Robert Brandon, an uncle of Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk.[33]

John Carew (d.1529)

John Carew (d.1529) of Haccombe, eldest son and heir, who survived his father by just one year. He married Elizabeth Martyn, a daughter of Christopher Martyn and sister of Richard Martyn.[34]

Thomas Carew (1518–1586)

Thomas Carew (1518–1586)[35] of Haccombe, eldest son and heir. He was a minor aged 11 at the death of his father and his wardship was acquired by William Hody (d.1535) of Pilsdon in Dorset, whose will directed "that his executors, Anne (Strode) his wife, and John his son, shall have ward of Thomas Carewe, son and heir of John Carewe, late of Haccombe, Devon, for the use of Mary, his daughter."[36] Thomas Carew was thus duly married-off to Mary Hody (d.1589), a daughter of William Hody (d.1535) of Pilsdon[37] in Dorset, by his second wife Anne Strode, a daughter of John Strode of Chalmington in Dorset.[38] Mary's grandfather was Sir William Hody (born before 1441, died 1524) of Pilsdon,[39]Attorney General of England and Chief Baron of the Exchequer under King Henry VII. Thomas Carew died aged 68 on 28 March 1586 of "Gaol Fever",[40] now believed to have been typhus, following his attendance as a magistrate at the notorious Black Assize of Exeter which commenced on 14 March 1586, which fever killed many others amongst his fellow magistrates and attendees at the Exeter Courthouse in Exeter Castle.

His monumental brass survives in Haccombe Church, on the floor of the chancel and next to that of his great-grandfather Nicholas Carew (died 1469), and is inscribed in Latin as follows:

- Hic jacet corpus Thomae Carewe, Armigeri, qui obiit 28 die Martii A(nn)o D(omi)ni 1586 aetatis suae 68[41] ("Here lies the body of Thomas Carew, Esquire, who died on the 28th day of March in the year of our Lord 1586 (in the year) of his age 68"

The monumental brass of his wife adjoins, inscribed in Latin as follows:

- Hic jacet Maria Carewe uxor Thom(a)e Carewe de Haccombe, Ar(migeri) et filia Will(iel)mi Huddye de com(itatu) Dorset, Ar(migeri), quae obiit XIXo[42] die Novembris Anno Domini 1589[43] ("Here lies Mary Carew, wife of Thomas Carew of Haccombe, Esquire, and a daughter of William Huddye from the county of Dorset, who died on the 19th day of November in the year of our Lord 1589")

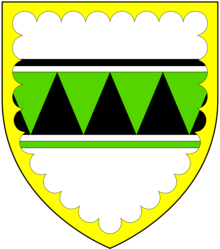

On the ledger stone of Mary Hody is a brass heraldic shield showing the arms of Carew impaling Hody of Pilsdon: Argent, a fess per fess indented vert and sable between two cotises counterchanged of the fess a bordure engrailed (or?). The bordure engrailed (tincture unknown), as shown on the brass, of which the lower half is missing, appears to be a difference of the arms of the senior branch of the family, Hody of Stowell, Somerset: Argent, a fess per fess indented vert and sable between two cotises counterchanged of the fess.[44] (Mary's great-grandfather was Sir John Hody (died 1441) of Stowell in Somerset and of Pilsdon in Dorset, Chief Justice of the King’s Bench). The Haccombe brass shows a mullet in chief, the difference of a 3rd son, although most sources[45] state William Hody, father of Mary Hody, to have been a 2nd son.

Sir Rivers Carew Bt assigned the Manor of Haccombe with Combeinteignhead to Colonel Gerald Arnold, together with the Patronage of the Benefice of Haccombe, Combeinteignhead. Stokeinteignhead, Ringmore and Shaldon in March 2010.

Archpriest of Haccombe

Persons to have held the office of Archpriest of Haccombe include:

- 1581-1594: John Woolton (1535?–1594), Bishop of Exeter from 1579 to 1594, who "as the bishopric had become of small value, was allowed to hold with it the place of archpriest at Haccombe (20 Oct. 1581) and the rectory of Lezant in Cornwall (1584)".[46]

Notes

- ↑ An heiress mother who was married to a wealthy husband frequently left her inheritance to a younger son, often with a stipulation that he should adopt her paternal surname and arms, in order effectively to continue a family which had expired in the male line. See for example Sir Theobald Gorges, the subject of the famous lawsuit Warbelton v Gorges.

References

- ↑ Risdon, p.377

- ↑ New Georgian house at Haccombe painted by Swete in July 1795, see: Gray, Todd & Rowe, Margery (Eds.), Travels in Georgian Devon: The Illustrated Journals of The Reverend John Swete, 1789–1800, 4 vols., Tiverton, 1999, Vol.2, p.159; built "in about 1800" per Pevsner, Nikolaus & Cherry, Bridget, The Buildings of England: Devon, London, 2004, p.464

- 1 2 Hoskins, W.G., A New Survey of England: Devon, London, 1959 (first published 1954), p.402

- ↑ Pevsner, p.464

- ↑ John Carnell. Will of Archpriest of Haccombe. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- ↑ Pole, p.485

- ↑ Risdon, p.140, who starts his passage with Stephen de Haccombe

- 1 2 3 4 5 Pole, p.249

- ↑ Pole, p.468

- 1 2 3 4 Risdon, p.140

- ↑ Pole, p.249; Risdon, p.140

- ↑ In March 1401 (John) Trevarthian arranged the marriage of his son, Otto, to a daughter of one of the oldest of Cornish families.... Elizabeth (Talbot), the widow of Sir Warin Archdeacon, agreed that the boy might marry Elizabeth, her late husband’s daughter and coheir. The other three daughters were married to Sir Walter Lucy, Sir Thomas Arundell, and Sir Hugh Courtenay. J.S. Roskell, L. Clark, C. Rawcliffe, eds. (1993), "Trevarthian, John (c.1360-1402), of Trevarthian in St. Hilary, Cornwall", The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1386-1421, retrieved 30 October 2017

- ↑ Debrett's Peerage, 1968, Carew Baronets, p.155; Baron Carew p.216

- ↑ Vivian, pp.134,245; Pole, p.249

- ↑ Vivian, pp.134,144; Risdon, p.140

- ↑ Address of 10th Carew Baronet per Debrett's Peerage, 1968, p.155; Haccombe Parva (Latin, "Little Haccombe"), Killiney, Co. Dublin, Ireland

- ↑ Vivian, p.144

- ↑ Vivian, p.145

- ↑ Risdon, p.140, who misses out a generation of de Veres

- ↑ Vivian, p.254, pedigree of Croker of Lyneham; she is called Elizabeth in the Carew pedigree, p.134

- ↑ Vivian, p.134, but not mentioned in Croker pedigree p.254 nor in Seymour pedigree p.702

- ↑ Vivian, p.254, pedigree of Croker of Lyneham; he is called William in the Carew pedigree, p.134

- ↑ Vivian, p.254

- ↑ Stabb, John, Some Old Devon Churches, Their Rood Screens, Pulpits, Fonts, Etc., 3 Vols., London: Vol 1, 1908, Index; Vol.2, 1911; Vol.3, 1916

- ↑ Transcribed variously (with varying degrees of accuracy and conjecture) by Stabb and by Prince, John, (1643–1723) The Worthies of Devon, 1810 edition, London, p.166

- ↑ i.e. quadringentensimo = "on the four hundredth"

- ↑ ratis ("calculated/reckoned") and numerato ("numbered") contrast the two methods of dating given here, regnal dates and dates from the birth of Christ

- ↑ Prince, p.167

- ↑ Risdon, p.141, quoted and expanded by Prince, p.167

- ↑ Odet de Foys alias Monsieur de Lotretch / Lautrecc, per Risdon, p.141; Prince, p.167

- ↑ Prince, p.167

- ↑ Prince, p.167, "Additional Note"

- ↑ Vivian, p.144

- ↑ Vivian, p.144

- ↑ Date of death per Vivian, p.144; date of birth deduced from his monumental brass which states he died aged 68, although he was said to have been aged 9 in 1529, the date of his father's inquisition post mortem, which would give a birth date of 1520

- ↑

- ↑ "Pillistone" per Vivian, p.144

- ↑ Heraldic Visitation of Dorset 1565, p.21

- ↑ Heraldic Visitation of Dorset 1565, p.21

- ↑ Jenkins, Alexander, Civil and Ecclesiastical History of the City of Exeter and its Environs, 2nd edition, Exeter, 1841, p. 125

- ↑ Quoted (abbreviated) by Prince, p.166

- ↑ i.e. undevicensimo

- ↑ Transcribed from brass; quoted (with inaccuracies) by Prince, p.166

- ↑ Burke's General Armory, 1884, p.515 Also p.496, Hody

- ↑ Heraldic Visitation of Dorset 1565, p.21

- ↑ Dictionary of National Biography

Sources

- Pole, Sir William (died 1635), Collections Towards a Description of the County of Devon, Sir John-William de la Pole (ed.), London, 1791.

- Risdon, Tristram (died 1640), Survey of Devon. With considerable additions. London, 1811.

- Vivian, Lt.Col. J.L., (Ed.) The Visitations of the County of Devon: Comprising the Heralds' Visitations of 1531, 1564 & 1620. Exeter, 1895.

- Prince, John, (1643–1723) The Worthies of Devon, 1810 edition, London, pp.164-167, descent of Haccombe, with descriptions and transcripts of several monuments in Haccombe Church.

_Nord-France.svg.png)