H-II Transfer Vehicle

| |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| Role: | Automated cargo spacecraft to resupply the International Space Station |

| Crew: | None |

| Dimensions | |

| Height: | ~9.8 m (including thrusters)[1] |

| Diameter: | 4.4 m[1] |

| Spacecraft Mass: | 10,500 kg[1] |

| Total Launch Payload: | 6,000 kg[2] / 6,200 kg[3] |

| Pressurized Payload: | 5,200 kg[2] |

| Unpressurized Payload: | 1,500 kg[2] / 1,900 kg (HTV-6 - )[4] |

| Return Payload: | None[5] |

| Mass at launch: | 16.5 ton[2] |

| Pressurized Volume: | 14 m3[6] |

| Performance | |

| Endurance: | Solo flight about 100 hours, stand-by more than a week, docked with the ISS about 30 days[1] |

| Apogee: | 460 km[1] |

| Perigee: | 350 km[1] |

| Inclination: | 51.6 degrees[1] |

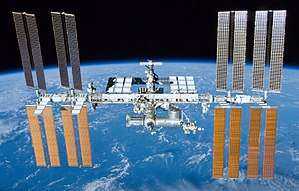

The H-II Transfer Vehicle (HTV), also called Kounotori (こうのとり Kōnotori, "Oriental stork" or "white stork"), is an automated cargo spacecraft used to resupply the Kibō Japanese Experiment Module (JEM) and the International Space Station (ISS). The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) has been working on the design since the early 1990s. The first mission, HTV-1, was originally intended to be launched in 2001. It launched at 17:01 UTC on 10 September 2009 on an H-IIB launch vehicle.[7] The name Kounotori was chosen for the HTV by JAXA because "a white stork carries an image of conveying an important thing (a baby, happiness, and other joyful things), therefore, it precisely expresses the HTV's mission to transport essential materials to the ISS".[8]

Design

The HTV is about 9.8 metres (32 ft) long (including maneuvering thrusters at one end) and 4.4 metres (14 ft) in diameter. Total mass when empty is 10.5 tonnes (11.6 short tons), with a maximum total payload of 6,000 kilograms (13,000 lb; 6.0 t; 6.6 short tons), for a maximum launch weight of 16.5 tonnes (18.2 short tons).[1] The HTV is comparable in function to the Russian Progress, European ATV, commercial Dragon, and commercial Cygnus spacecraft, all of which bring supplies to the ISS. Like the ATV, the HTV carries more than twice the payload of the Progress, but is launched less than half as often. Unlike Progress capsules and ATVs, which use the docking ports automatically, HTVs and American commercial spacecraft approach the ISS in stages, and once they reach their closest parking orbit to the ISS, crew grapple them using the robotic arm Canadarm2 and berth them to an open berthing port on the Harmony module.[9]

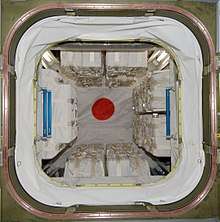

The HTV has an external payload bay which is accessed by robotic arm after it has been berthed to the ISS. New payloads can be moved directly from the HTV to Kibō's exposed facility. Internally, it has eight International Standard Payload Racks (ISPRs) in total which can be unloaded by the crew in a shirt-sleeve environment. After the retirement of NASA's Space Shuttle in 2011, HTVs became the only spacecraft capable of transporting ISPRs to the ISS. The SpaceX Dragon and Orbital Sciences Cygnus can carry resupply cargo bags but not ISPRs.

The intention of HTV's modularized design was to use different module configuration to match the mission requirement.[10] However, to reduce the development cost it was decided to fly the mixed PLC/ULC configuration only.[10]

To control the HTV's attitude and to perform the orbital maneuvers such as rendezvous and re-entry, the craft has four 500 N class main thrusters and twenty-eight 110 N class attitude control thrusters. Both use bipropellant, namely monomethylhydrazine (MMH) as fuel and mixed oxides of nitrogen (MON3) as oxidizer.[11] HTV-1, -2, and -4 use Aerojet's 110 N R-1E, Space Shuttle's vernier engine, and the 500 N based on the Apollo spacecraft's R-4D.[11] Later HTVs use 500 N class HBT-5 thrusters and 120 N class HBT-1 thrusters made by Japanese manufacturer IHI Aerospace Co., Ltd.[12] The HTV carries about 2400 kg of propellant in four tanks.[11]

After the unloading process is completed, the HTV will be loaded with waste and unberthed. The vehicle will then deorbit and be destroyed during reentry, the debris falling into the Pacific Ocean.[5]

Flights

Initially seven missions were planned in 2008-2015. With the extension of ISS project after 2015 through 2020, three more missions are planned, possibly replacing the tenth flight with an improved, cost-reduced version (HTV-X).[13]

The first vehicle was launched on an H-IIB rocket, a more powerful version of the earlier H-IIA, at 17:01 GMT on 10 September 2009, from Launch Pad 2 of the Yoshinobu Launch Complex at the Tanegashima Space Center.[14]

As of March 2015, five subsequent missions are planned—one each year for 2015–2019[15] —one fewer total mission than had been planned in August 2013 at the time the fourth HTV mission was underway.[16]

| HTV | Launch date/time (UTC) | Berth date/time (UTC)[17] | Carrier rocket | Re-entry date/time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HTV-1 | 10 September 2009, 17:01:56 | 17 September 2009, 22:12 | H-IIB F1 | 1 November 2009, 21:26[18] |

| HTV-2 | 22 January 2011, 05:37:57 | 27 January 2011, 14:51 | H-IIB F2 | 30 March 2011, 03:09[19] |

| HTV-3 | 21 July 2012, 02:06:18 | 27 July 2012, 14:34 | H-IIB F3 | 14 September 2012, 05:27 |

| HTV-4 | 3 August 2013, 19:48:46 | 9 August 2013, 15:38 | H-IIB F4[20] | 7 September 2013, 06:37[21] |

| HTV-5 | 19 August 2015, 11:50:49 | 24 August 2015, 17:28 [22] | H-IIB F5 | 29 September 2015, 20:33[23] |

| HTV-6 | 9 December 2016, 13:26:47 | 13 December 2016, 18:24 | H-IIB F6 | 5 February 2017, 15:06 |

| HTV-7 | 22 September 2018, 17:52:27 | 27 September 2018, 18:08 | H-IIB F7 | |

| HTV-8 | 2019[15] | H-IIB | ||

| HTV-9 | 2020[15] | H-IIB |

Planned successor

HTV-X

In May 2015, Japan's Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology announced a proposal to replace HTV with an improved, cost-reduced version preliminary called HTV-X.[13][24]

Proposed concept of HTV-X as of July 2015 is:[25]

- To re-use the design of HTV's Pressurized Logistics Carrier (PLC) as much as possible, except adding a side hatch for late access cargo,

- To replace the Unpressurized Logistics Carrier, Avionics Module, and Propulsion Module with a new Service Module

- Instead of loading the unpressurized cargo inside the spacecraft, load them on top of the Service Module.

Re-using the PLC design will allow minimizing the development cost and risk. Concentrating the Reaction Control System (RCS) and the solar panels to Service Module will allow simplifying the wiring and piping, to reduce the weight and the manufacturing cost. Loading the unpressurized cargo outside the spacecraft allows larger cargo, only limited by the launch vehicle fairing. The aim is to cut the cost in half, while keeping or extending the capability of existing HTV.[25]

The simplification of overall structure will allow the launch mass of HTV-X to be dropped to 15.5 t (planned) from HTV's 16.5 t, while the maximum weight of cargo will be increased to 7.2 t (net weight 5.85 t excluding support structure weight) from HTV's 6.0 t (net 4.0 t).[26]

In December 2015, the plan to develop HTV-X was approved by the Strategic Headquarters for Space Policy of the Cabinet Office, targeting fiscal year 2021 for the flight of HTV-X1 (Technical Demonstration Vehicle) to be launched by H3 rocket.[27][26]

With the agreement of Japan-US Open Platform Partnership Program (JP-US OP3) in December 2015 to extend the cooperation of ISS operation through 2024, Japan will provide its share of ISS operation costs with the form of transportation by HTV-X, and also a possibility to develop a small return capsule.[28]

The final form of the HTV-X consists of three modules; a lower 3.5 m long pressurised logistics module nearly identical to that of the HTV elongated by 0.2 m and with a side access hatch added to allow late loading while mated to the rocket, a 2.7 m long central service module containing all functions and capable of operating independently of the other modules, two arrays of solar panels generate 1 kW of electrical power as opposed to the 200 W generated by the HTV, in addition the Service Module batteries are capable of providing a peak output of 3 kW compared to the 2 kW of the original and a 1 Mbit/s communication link has been added in addition to the original 8 kbit/s link,[29] the main thrusters have been removed and the HTV-X is purely reliant on Reaction Control System (RCS) motors mounted in a ring around the service module and selected service module components have been mounted externally on the top of the service module sitting beneath an attached unpressurised cargo module to allow for ease of maintenance access in space. Finally the 3rd module by default is a 3.8 m long unpressurised cargo module, essentially a hollow cylinder with shelves it vastly expands the volume of unpressurised cargo which can be stored compared to the storage compartments built in to the outside of the original HTV and it can be optionally replaced with a different mission payload. The HTV-X has a length of 6.2 m or 10 m with the unpressurised cargo module fitted, the payload fairing adaptor and payload dispenser have been widened from 1.7 m to 4.4 m to accommodate replacing of pressurised module with alternate modules, add increased structural strength and to accommodate the side hatch.[30]Other payloads being considered to replace the unpressurised cargo module while carrying out ISS resupply missions are an external sensor package, a technology trial of an IDSS airlock with automated station docking as used by the Progress and ATV craft, a trial of rendezvous and docking with a simulated satellite module, a smaller satellite piggybacking the launch to reach ISS orbit, a station return capsule, assembling a beyond earth orbit mission such as lunar lander from smaller modules and acting as a space tug shuttling orbiting unpressurised cargo modules to the ISS allowing stuff such as recyclable materials, excess propellant and spare parts to be stored in orbit for future use rather than discarded.[30]

Former evolutionary proposals

HTV-R

As of 2010, JAXA was planning to add a return capsule option. In this concept, HTV's pressurized cargo would be replaced by a reentry module capable of returning 1.6 tonnes (1.8 tons) cargo from ISS to Earth.[31][32]

Further, conceptual plans in 2012 included a follow-on spacecraft design by 2022 which would accommodate a crew of three and carry up to 400 kilograms (880 lb) of cargo.[33]

Lagrange outpost resupply

As of 2014, both JAXA and Mitsubishi conducted studies of a next generation HTV as a possible Japanese contribution to the proposed international manned outpost at Earth-Moon L2.[34][35] This variant of HTV was to be launched by H-X Heavy and can carry 1.8 tons of supplies to EML2.[34] Modifications from the current HTV includes the addition of solar electric paddles and extension of the propellant tank.[34]

Manned variant

A proposal announced in June 2008 suggested combining HTV's propulsion module with a manned capsule for four people.[36]

Japanese Space Station

A Japanese Space Station has been proposed to be built up from HTV modules.[37] This method is similar to how the modules in Mir, as well as many modules of the Russian Orbital Segment of the ISS are based on the TKS cargo vehicle design.

Gallery

HTV-3 near ISS

HTV-3 near ISS Kounotori 5 (HTV-5) with Aurora australis

Kounotori 5 (HTV-5) with Aurora australis.jpg) HTV-6 grappled to a robotic arm of ISS

HTV-6 grappled to a robotic arm of ISS

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "H-II Transfer Vehicle "KOUNOTORI" (HTV)". Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. 2007. Archived from the original on 2010-11-16. Retrieved 2010-11-11.

- 1 2 3 4 Overview of the "KOUNOTORI" Archived 2010-11-15 at the Wayback Machine.. Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. Retrieved 2011-01-18.

- ↑ 「こうのとり」(HTV)5号機の搭載物変更について (PDF). 31 July 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ↑ 宇宙ステーション補給機「こうのとり」6号機(HTV6)【ミッションプレスキット】 (PDF) (in Japanese). JAXA. 24 November 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 December 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- 1 2 JAXA (2007). "HTV Operations". Archived from the original on 2011-01-26. Retrieved 2011-01-02.

- ↑ "JAXA H-II Transfer Vehicle (HTV)" (PDF). NASA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 June 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ↑ "NASA Sets Briefing, TV Coverage of Japan's First Cargo Spacecraft". NASA. Archived from the original on 2011-08-11. Retrieved 2009-09-03.

- ↑ ""KOUNOTORI" Chosen as Nickname of the H-II Transfer Vehicle (HTV)". JAXA. 11 November 2010. Archived from the original on 22 December 2010. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ↑ http://www.aprsaf.org/data/aprsaf17_data/DAY1-seu_0950-Kibo_Utilization_Status.pdf Archived March 17, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Miki, Yoichiro; Abe, Naohiko; Matsuyama, Koichi; Masuda, Kazumi; Fukuda, Nobuhiko; Sasaki, Hiroshi (March 2010). "Development of the H-II Transfer Vehicle (HTV)" (PDF). Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Technical Review. Mitsubishi Heavy Industries. 47 (1). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-07-20.

- 1 2 3 IAC paper IAC-05-C4.1.03 - Shinobu Matsuo and al. "The design characteristics of the HTV propulsion module"

- ↑ "宇宙ステーション補給機「こうのとり」3号機(HTV3)ミッションプレスキット" (PDF) (in Japanese). June 20, 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 31, 2012. Retrieved 2012-06-24.

- 1 2 Research and Development Division, Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (May 20, 2015). 2016年~2020年のISS共通システム運用経費(次期CSOC)の我が国の負担方法の在り方について (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on June 5, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ Launch of the H-IIB Launch Vehicle Test Flight Archived 2009-07-11 at the Wayback Machine., JAXA Press release, 8 July 2009 (JST)

- 1 2 3 "International Space Station Flight Schedule". SEDS. 2015-03-13. Archived from the original on 27 March 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ↑ "International Space Station Flight Schedule". SEDS. 15 May 2013. Archived from the original on 14 July 2013. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- ↑ "H-II Transfer Vehicle "KOUNOTORI" (HTV) Topics". Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. Archived from the original on 2013-08-22.

- ↑ Stephen Clark (1 November 2009). "History-making Japanese space mission ends in flames". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 11 March 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

- ↑ Stephen Clark (29 March 2011). "Japan's HTV cargo freighter proves useful to the end". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 19 April 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- ↑ Stephen Clark (3 August 2013). "Japan launches resupply mission to space station". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 25 September 2013. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ↑ Stephen Clark (9 August 2013). "JJapan's cargo craft makes in-orbit delivery to space station". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 14 August 2013. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- ↑ "Successful berthing of the H-II Transfer Vehicle KOUNOTORI5 (HTV5) to the International Space Station (ISS)". Archived from the original on 2016-11-04.

- ↑ "Successful re-entry of H-II Transfer Vehicle "KOUNOTORI5" (HTV5)". JAXA. September 30, 2015. Archived from the original on October 1, 2015. Retrieved September 30, 2015.

- ↑ "国際宇宙ステーション計画を含む有人計画について" (PDF) (in Japanese). June 3, 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 13, 2015. Retrieved July 13, 2015.

- 1 2 HTV-X(仮称)の開発(案)について (PDF) (in Japanese). July 2, 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 20, 2015. Retrieved July 17, 2015.

- 1 2 JAXA (14 July 2016). HTV‐Xの開発状況について (PDF) (in Japanese). Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 July 2016. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- ↑ Strategic Headquarters for Space Policy (8 December 2015). 宇宙基本計画工程表(平成27年度改訂) (PDF) (in Japanese). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 October 2016. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- ↑ "Japan - United States Space Cooperation and the International Space Station Program" (PDF). Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology. 22 December 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- ↑ http://www.jaxa.jp/press/2017/12/files/20171206_HTV-X.pdf

- 1 2 "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-07-15. Retrieved 2016-07-18.

- ↑ "回収機能付加型宇宙ステーション補給機(HTV-R)検討状況" (in Japanese). JAXA. August 11, 2010. Archived from the original on September 14, 2010. Retrieved September 7, 2011.

- ↑ "回収機能付加型HTV(HTV-R)" (in Japanese). JAXA. Archived from the original on August 26, 2011. Retrieved September 7, 2011.

- ↑ Rob Coppinger. "Japan Wants Space Plane or Capsule by 2022". Space.com. Archived from the original on December 24, 2015. Retrieved October 25, 2012.

- 1 2 3 "International Human Lunar Mission Architecture / System and its Technologies" (PDF). JAXA. 2014-04-10. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 April 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- ↑ "An International Industry Perspective on Extended Duration Missions Near the Moon" (PDF). Lockheed Martin Corporation. 2014-04-10. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 April 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- ↑ Takane Imada; Michio Ito; Shinichi Takata (June 2008). "Preliminary Study for Manned Spacecraft with Escape System and H-IIB Rocket" (PDF). 26th ISTS. Retrieved 2010-12-25.

- ↑ Sasaki, Hiroshi; Imada, Takane; Takata, Shinichi (2008). "Development Plan for Future Mission from HTV System" (PDF). JAXA. Retrieved 2016-07-19.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to H-II Transfer Vehicle. |

- Project overview of H-II Transfer Vehicle., JAXA

- HTV/H-IIB launch Special site, JAXA

- For Future Space Transportation Mission -HTV/H-IIB Promotional Movie on YouTube. JAXA

- H-II Transfer Vehicle -Road to the HTV's launch-, JAXA

- HTV1/H-IIB TF Quick Review on YouTube. JAXA

- H-2B rocket and Kounotori 3D model, Asahi Shinbun

- Japan's space freighter in orbit, BBC News