Gun laws in Australia

| Gun laws by country |

|---|

Gun laws in Australia are mainly the jurisdiction of Australian states and territories, with the importation of guns regulated by the federal government. In the last two decades of the 20th century, following several high-profile killing sprees, the federal government coordinated more restrictive firearms legislation with all state governments. Gun laws were largely aligned in 1996 by the National Firearms Agreement.

A person must have a firearm licence to possess or use a firearm. Licence holders must demonstrate a "genuine reason" (which does not include self-defence) for holding a firearm licence[1] and must not be a "prohibited person". All firearms must be registered by serial number to the owner, who also holds a firearms licence.

Studies on the effects of Australia's gun laws have argued that the laws have been effective in reducing mass shootings, gun suicides and armed crime,[2][3] while other studies have argued that the laws have had little effect.[4][5] Polling shows strong support for gun legislation in Australia with around 85-90% of people wanting the same or greater level of restrictions.[6][7][8][9]

Overview

The first gun law in Australia was an order in 1807 of New South Wales Governor William Bligh that:

- "all Persons who have arms [are]... to be registered in a Book kept by the Magistrate".

Over the next 100 years, some regulations to punish poachers and to privilege the gentry were added, following British patterns. During World War I, social changes in Europe and soldiers returning with war-weapons changed the focus from the perceived problem of guns to that of crime, social control and the government's monopoly on violence.

All Australian states and territories enacted gun control regulations between 1921 and 1931. The Firearms and Guns Act 1931 (Western Australia) permitted possession of rifles and shotguns in Western Australia, while other jurisdictions allowed possession of registered handguns only. Until 1981, five out of the eight jurisdictions did not require registration of long guns. Tasmania and Queensland had no licensing or registration requirements; Victoria, New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory had licenses for uncounted long arms without single registration. Between 1984 and 1987, in Victoria, 60% of long guns were registered.

National legislative structure

Following the shooting incidents at Port Arthur in 1996 and Monash University in 2002 the Australian state and territory governments, through the then Australian Police Ministers' Council (APMC) and Council of Australian Governments (COAG), entered into three national agreements that were responsible for shaping contemporary Australian firearm laws. These agreements were the:

- National Firearms Agreement (1996);

- National Firearm Trafficking Policy Agreement (2002); and

- National Handgun Control Agreement (2002).[10]

The ownership, possession and use of firearms in Australia is regulated by state laws. The Australian state and territory laws regulating firearms are:[11]

- New South Wales: Firearms Act 1996,[12] Weapons Prohibition Act 1998,[13] and associated regulations;

- Victoria: Firearms Act 1996,[14] and associated regulations;

- Queensland: Weapons Act 1990,[15] and associated regulations;

- Western Australia: Firearms Act 1973,[16] and associated regulations;

- South Australia: Firearms Act 2015,[17] and associated regulations;

- Tasmania: Firearms Act 1996,[18] and associated regulations;

- Northern Territory: Firearms Act,[19] and associated regulations

- Australian Capital Territory: Firearms Act 1996,[20] Prohibited Weapons Act 1996, and associated regulations.[11]

At the federal level, the importation of firearms is subject to the restrictions in Regulation 4F and Schedule 6 of the Customs (Prohibited Imports) Regulations 1956 (Cth). [21]

Firearms categories

The National Firearm Agreement defines categories of firearms, with different levels of control for each, as follows:.

- Category A

- Rimfire rifles (not semi-automatic), shotguns (not pump-action or semi-automatic), air rifles including semi-automatic, and paintball guns.

- Category B

- Centrefire rifles including bolt action, pump action and lever action (not semi-automatic) and muzzleloading firearms made after 1 January 1901.

- Category C

- Pump-action or self-loading shotguns having a magazine capacity of 5 or fewer rounds and semi-automatic rimfire rifles up to 10 rounds. Primary producers, farm workers, firearm dealers, firearm safety officers, collectors and clay target shooters can own functional Category C firearms.

- Category D

- All self-loading centrefire rifles, pump-action or self-loading shotguns that have a magazine capacity of more than 5 rounds, semi-automatic rimfire rifles over 10 rounds, are restricted to government agencies, occupational shooters and primary producers.

- Category H

- Handguns including air pistols and deactivated handguns. This class is available to target shooters and certain security guards whose job requires possession of a firearm. To be eligible for a Category H firearm, a target shooter must serve a probationary period of 6 months using club handguns, after which they may apply for a permit. A minimum number of matches yearly to retain each category of handgun and be a paid-up member of an approved pistol club.[22] Target shooters are limited to handguns of .38 or 9mm calibre or less and magazines may hold a maximum of 10 rounds. Participants in certain "approved" pistol competitions may acquire handguns up to .45 calibre, currently Single Action Shooting and Metallic Silhouette. IPSC shooting is approved for 9mm/.38/.357 SIG, handguns that meet the IPSC rules, larger calibres such as .45 were approved for IPSC handgun shooting contests in Australia in 2014, however only in Victoria so far.[23] Barrels must be at least 100mm (3.94") long for revolvers, and 120mm (4.72") for semi-automatic pistols unless the pistols are clearly ISSF target pistols; magazines are restricted to 10 rounds.

- Category R/E

- Restricted weapons include military weapons such as machine guns, rocket launchers, full automatic self loading rifles, flame-throwers and anti-tank guns.

Certain antique firearms (generally muzzle loading black powder flintlock firearms manufactured before 1 January 1901) can in some states be legally held without a licence.[24] In other states they are subject to the same requirements as modern firearms.[25] All single-shot muzzleloading firearms manufactured before 1 January 1901 are considered antique firearms. Four states require licences for antique percussion revolvers and cartridge repeating firearms, but in Queensland and Victoria a person may possess such a firearm without a licence, so long as the firearm is registered (percussion revolvers require a licence in Victoria).

Licensing

The states issue firearms licences for a legal reason, such as hunting, sport shooting, pest control, collecting and for farmers and farm workers. Licences are prohibited for convicted offenders and those with a history of mental illness. Licences must be renewed every 3 or 5 years (or 10 years in the Northern Territory and South Australia). Full licence-holders must be 18 years of age; minor's permits allow the use of a firearm under adult supervision by those as young as 12 in most states.[26]

Handguns may be obtained by target shooters, primary producers in some states and certain security guards after serving a probationary six-month period with a shooting club. Restricted weapons include military weapons, high-capacity semi-automatic rifles and pump-action and semi-automatic shotguns holding more than 5 rounds.

Compliance with National Firearms Agreement

A 2017 study commissioned by Gun Control Australia claimed that Australian states had significantly weakened gun laws since the National Firearms Agreement was first introduced, with no jurisdiction fully compliant with the Agreement.[27][28] For example, many states now allow children to fire guns under strict supervision and the mandatory 28 day cooling-off period required for gun purchases has been relaxed, with no waiting period for purchasers who already own at least one gun.[27] New South Wales also allows the limited use of moderators via a permit even though they are supposed to be a prohibited weapon.[28] No state or territory has outlined a timeframe for achieving full compliance with the National Firearms Agreement.[29]

History

European settlement to 19th century

Firearms were introduced to Australia with European settlement on 26 January 1788, though other seafarers that visited Australia before settlement also carried firearms. The colony of New South Wales was initially a penal settlement, with the military garrison being armed. Firearms were also used for hunting, protection of persons and crops, in crime and fighting crime, and in many military engagements. From the landing of the First Fleet there was conflict with Aborigines over game, access to fenced land, and spearing of livestock. Firearms were used to protect explorers and settlers from Aboriginal attack. A number of punitive raids and massacres of Aboriginals were carried out in a series of local conflicts.

From the beginning, there were controls on firearms. The firearms issued to convicts (for meat hunting) and settlers (for hunting and protection) were stolen and misused, resulting in more controls. In January 1796, David Collins wrote that "several attempts had been made to ascertain the number of arms in the possession of individuals, as many were feared to be in the hands of those who committed depredations; the crown recalled between two and three hundred stands of arms, but not 50 stands were accounted for".[30]

Australian colonists also used firearms in conflict with bushrangers and armed rebellions such as the 1804 Castle Hill convict rebellion and the 1854 Eureka Stockade.

20th century

Gun laws were the responsibility of each colony and, since Federation in 1901, of each state. The Commonwealth does not have constitutional authority over firearms, but it has jurisdiction over customs and defence matters. Federally the external affairs powers can be used to enforce internal control over matters agreed in external treaties.

In New South Wales, handguns were effectively banned after World War II but the 1956 Melbourne Olympic Games sparked a new interest in the sport of pistol shooting and laws were changed to allow the sport to develop.

In some jurisdictions, individuals may also be subject to firearm prohibition orders (FPOs), which give police additional powers to search and question the individual for firearms or ammunition without a warrant. FPOs have been available in New South Wales since 1973,[31] and are also used in Victoria.[32]

In October 2016, it was estimated that there were 260,000 unregistered guns in Australia, 250,000 long arms and 10,000 handguns, most of them in the hands of organised crime groups and other criminals.[33] There are 3 million registered firearms in Australia.[33]

In March 2017, there were 915,000 registered firearms in New South Wales, 18,967 in the ACT, 298,851 in South Australia, and 126,910 in Tasmania. The other jurisdictions did not make the information public.[34]

In 2015, there were more private firearms in Australia than there were before the Port Arthur massacre, when 1 million firearms were destroyed.[35]

There has been an incremental move since the 1970s for police forces in the eight jurisdictions in Australia to routinely carry exposed firearms while on duty. In the 1970s the norm was for police to carry a baton, with only NSW police carrying firearms. Since then, police have been authorised to carry a covered firearm, and then to carry an exposed firearm. The shift has taken place without public debate or a proper assessment of the vulnerability of police officers, but has taken place with public acquiescence.[36]

1984–1996 multiple killings

From 1984 to 1996, multiple killings aroused public concern. The 1984 Milperra massacre was a major incident in a series of conflicts between various "outlaw motorcycle gangs". In 1987, the Hoddle Street massacre and the Queen Street massacre took place in Melbourne. In response, several states required the registration of all guns, and restricted the availability of self-loading rifles and shotguns. In the Strathfield massacre in New South Wales, 1991, two were killed with a knife, and five more with a firearm. Tasmania passed a law in 1991 for firearm purchasers to obtain a licence, though enforcement was light. Firearm laws in Tasmania and Queensland remained relatively relaxed for longarms.

Shooting massacres in Australia and other English-speaking countries often occurred close together in time. Forensic psychiatrists attribute this to copycat behaviour,[37][38] which is in many cases triggered by sensational media treatment.[39][40] Mass murderers study media reports and imitate the actions and equipment that are sensationalised in them.[41]

Port Arthur massacre

The Port Arthur massacre took place in 1996 when the gunman opened fire on shop owners and tourists with two semi-automatic rifles that left 35 people dead and 23 wounded. This mass killing horrified the Australian public and transformed gun control legislation in Australia.

Prime Minister John Howard convinced the states to adopt the gun law proposals made in a report of the 1988 National Committee on Violence as the National Firearms Agreement.[42] The Australian Constitution does not give the Commonwealth power to enact gun laws. In the face of some state resistance, Howard threatened to hold a nationwide referendum to alter the Australian Constitution to give the Commonwealth constitutional power over guns.[43] The proposals included a ban on all semi-automatic rifles and all semi-automatic and pump-action shotguns, and a system of licensing and ownership controls.

The Howard Government held a series of public meetings to explain the proposed changes. In the first meeting, Howard wore a bullet-resistant vest, which was visible under his jacket. Many shooters were critical of this.[44][45][46] Some firearm owners applied to join the Liberal Party in an attempt to influence the government, but the party barred them from membership.[47][48] A court action by 500 shooters seeking admission to membership eventually failed in the Supreme Court of South Australia.[49]

The Australian Constitution requires just compensation be given for property taken over, so the federal government introduced the Medicare Levy Amendment Act 1996 to raise the predicted cost of A$500 million through a one-off increase in the Medicare levy. The gun buy-back scheme started on 1 October 1996 and concluded on 30 September 1997.[50] The government bought back and destroyed over 1 million firearms.[51]

Monash University shootings

In October 2002, a commerce student killed two fellow students at Monash University in Victoria with pistols he had acquired as a member of a shooting club. The gunman, Huan Yun Xiang, was acquitted of crimes related to the shootings due to mental impairment but ordered to be detained in Thomas Embling Hospital, a high-security hospital for up to 25 years.[52]

As in 1996, the federal government urged state governments to review handgun laws, and amended legislation was adopted in all states and territories. Changes included a 10-round magazine capacity limit, a calibre limit of not more than .38 inches (9.65 mm) (since expanded under certain criteria), a barrel length limit of not less than 120 mm (4.72 inches) for semi-automatic pistols and 100 mm (3.94 inches) for revolvers, and even stricter probation and attendance requirements for sporting target shooters. Whilst handguns for sporting shooters are nominally restricted to .38 inches as a maximum calibre, it is possible to obtain an endorsement allowing calibres up to .45 inches (11.43 mm) to be used for metallic silhouette or Single Action Shooting matches. These new laws were opposed not only by sporting shooters groups but also by gun control supporters, who saw it as paying for shooters to upgrade to new guns.

One government policy was to compensate shooters for giving up the sport. Approximately 25% of pistol shooters took this offer, and relinquished their licences and their right to own pistols for sport for five years; in Victoria it is estimated 1/3 of people surrendering firearms took this option.[53]

2014 Sydney hostage crisis

On 15–16 December 2014, a lone gunman, Man Haron Monis, held hostage 17 customers and employees of a Lindt chocolate café located at Martin Place in Sydney, Australia. The perpetrator was on bail at the time and had previously been convicted of a range of offences.[54] Two of the hostages and the perpetrator died.

In August 2015, Mike Baird and Troy Grant announced a tightening of laws on bail and illegal firearms, creating a new offence for the possession of a stolen firearm, with a maximum of 14 years imprisonment and establishing an Illegal Firearms Investigation and Reward Scheme. This legislative change also introduced measures to reduce illegal firearms in NSW including a ban on the possession of digital blueprints that enable firearms to be manufactured using 3D printers and milling machines for anyone without an appropriate licence.[55]

Gun amnesties

In New South Wales there have been three gun amnesties in 2001, 2003 and 2009. 63,000 handguns were handed in during the first two amnesties and over 4,323 handguns were handed in during the third amnesty. During the third amnesty 21,615 firearm registrations were received by the Firearms Registry. The surrendered firearms were all destroyed.[56]

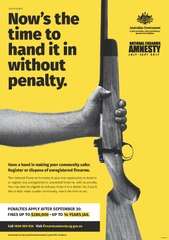

2017 national firearms amnesty

On 16 June 2017, the Minister for Justice Michael Keenan announced that a national firearms amnesty would commence on 1 July 2017 for three months until September 30, to hand in unregistered or unwanted firearms.[57] The amnesty had been approved in March 2017 by the Firearms and Weapons Policy Working Group (FWPWG) to reduce the number of unregistered firearms in Australia following the Lindt Cafe siege in 2014, and the 2015 shooting of an unarmed police civilian finance worker outside the New South Wales Police Force headquarters in Parramatta, Sydney.[58][59]

The firearms amnesty was the first national amnesty since the 1996 Port Arthur massacre.[57] In October 2017 Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull said that 51,000 unregistered firearms were surrendered during the three-month amnesty,[60] of the previous estimate of 260,000 unregistered guns.[61]

Measuring the effects of firearms laws in Australia

Measures and trends in social problems related to firearms

Between 1991 and 2001, the number of firearm-related deaths in Australia declined by 47%. Suicides committed with firearms accounted for 77% of these deaths, followed by firearms homicide (15%), firearms accidents (5%), firearms deaths resulting from legal intervention and undetermined deaths (2%). The number of firearms suicides was in decline consistently from 1991 to 1998, two years after the introduction of firearm regulation in 1996.[62]

Suicide deaths using firearms more than halved in ten years, from 389 deaths in 1995, to 147 deaths in 2005.[63] This is equal to 7% of all suicides in 2005. Over the same period, suicides by hanging increased by over 52% from 699 in 1995 to 1068 in 2005.[64]

The number of guns stolen fell from an average 4,195 per year from 1994 to 2000 to 1,526 in 2006–2007. Long guns are more often stolen opportunistically in home burglaries, but few homes have handguns and a substantial proportion of stolen handguns are taken from security firms and other businesses; only a small proportion, 0.06% of licensed firearms, are stolen in a given year. A small proportion of those firearms are reported to be recovered. About 3% of these stolen weapons are later connected to an actual crime or found in the possession of a person charged with a serious offence.[65] As of 2011 and 2012, pistols and semi-automatic pistols were traded on the black market for ten to twenty thousand dollars.[66]

Research

In 1997, the Prime Minister appointed the Australian Institute of Criminology to monitor the effects of the gun buyback. The institute has published a number of papers reporting trends and statistics around gun ownership and gun crime.[67][68]

Many studies have followed, providing varying results stemming from different methodologies and areas of focus. David Hemenway and Mary Vriniotis of Harvard University, funded by the Joyce Foundation summarized the research in 2011 and concluded; “it would have been difficult to imagine more compelling future evidence of a beneficial effect.” They said that a complication in evaluating the effect of the NFA was that gun deaths were falling in the early 1990s. They added that everyone should be pleased with the "immediate, and continuing, reduction" in firearm suicide and firearm homicide following the NFA.[69]

Suicide reduction from firearm regulation is disputed by Richard Harding in his 1981 book "Firearms and Violence in Australian Life"[70] where, after reviewing Australian statistics, he said that "whatever arguments might be made for the limitation or regulation of the private ownership of firearms, suicide patterns do not constitute one of them" Harding quoted a 1969 international analysis by Newton and Zimring[71] of twenty developed countries which concluded at page 36 of their report; "cultural factors appear to affect suicide rates far more than the availability and use of firearms. Thus, suicide rates would not seem to be readily affected by making firearms less available." Harding later supported 1985 laws to restrict gun ownership in New South Wales, saying that laws contributing to "slowing down in the growth of the Australian gun inventory" are "to be welcomed".[72]

In 2002, Jenny Mouzos from the Australian Institute of Criminology examined the rate of firearm theft in Australian states in territories following the firearm regulation. She found that "the NFA... is having the desired effect: securely stored firearms are proving less vulnerable to theft."[73]

In 2003, researchers from the Monash University Accident Research Centre examined firearm deaths and mortality in the years before and after firearm regulation. They concluded that there was "dramatic" reduction in firearm deaths and especially suicides due to "the implementation of strong regulatory reform".[74]

Multiple studies have been conducted by Dr Jeanine Baker and Dr Samara McPhedran, researchers with the International Coalition for Women in Shooting and Hunting (WiSH). In 2006 they reported a lack of a measurable effect from the 1996 firearms legislation in the British Journal of Criminology. Using ARIMA analysis, they found little evidence for an impact of the laws on homicide, but did for suicide.[75] Subsequently, they compared the incidence of mass shootings in Australia and New Zealand. Data were standardised to a rate per 100,000 people, to control for differences in population size between the countries and mass shootings before and after 1996/1997 were compared between countries. That study found that in the period 1980–1996, both countries experienced mass shootings. The rate did not differ significantly between countries. Since 1996-1997, neither country has experienced a mass shooting event despite the continued availability of semi-automatic longarms in New Zealand.[nb 1] The authors conclude that "if civilian access to certain types of firearms explained the occurrence of mass shootings in Australia then New Zealand would have continued to experience mass shooting events."[5] In 2012, McPhedran and Baker found there was little evidence for any impacts of the gun laws on firearm suicide among people under 35 years of age, and suggest that the significant financial expenditure associated with Australia's firearms method restriction measures may not have had any impact on youth suicide.[76] Head of the New South Wales Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, Don Weatherburn described the Baker and McPhedran article as "reputable" and "well-conducted" but also stated that "it would be wrong to infer from the study that it does not matter how many guns there are in the community." Simon Chapman stated this study ignored the Mass Shootings issue such as Port Arthur Massacre.[77] Weatherburn noted the importance of actively policing illegal firearm trafficking and argued that there was little evidence that the new laws had helped in this regard.[78] He also stated that the 1996 legislation had little to no effect on violence saying the "laws did not result in any acceleration of the downward trend in gun homicide." [79][80]

A 2006 study coauthored by Simon Chapman concluded: "Australia's 1996 gun law reforms were followed by more than a decade free of fatal mass shootings, and accelerated declines in firearm deaths, particularly suicides. Total homicide rates followed the same pattern. Removing large numbers of rapid-firing firearms from civilians may be an effective way of reducing mass shootings, firearm homicides and firearm suicides."[81]

In 2007, a meta-analysis published in the Australian Medical Association's The Medical Journal of Australia researched nationwide firearm suicides. They said that the analysis was consistent with the hypothesis that "measures to control the availability of firearms... have resulted in a decline in total suicide rates" and recommended further reduction in the availability of lethal means.[2]

A 2008 study on the effects of the firearm buybacks by Wang-Sheng Lee and Sandy Suardi of University of Melbourne and La Trobe University studied the data and concluded "the NFA did not have any large effects on reducing firearm homicide or suicide rates."[4]

In 2009 a study published in the Journal of Sociology examined the rate of firearm suicide in Queensland. They found that "gun suicides are continuing to decrease in Queensland" and is "most likely as a function of ongoing gun controls".[82]

In 2009 another paper from the Australian Institute for Suicide Research and Prevention at Griffith University also studied suicide in Queensland only. The said "No significant difference was found in the rate pre/post the introduction of the NFA in Queensland; however, a significant difference was found for Australian data, the quality of which is noticeably less satisfactory."[83]

A 2010 study by Christine Neill and Andrew Leigh found the 1997 gun buyback scheme reduced firearm suicides by 74% while having no effect on non-firearm suicides or substitution of method.[84]

A 2014 report stated that approximately "260,000 guns are on the Australian 'grey' or black markets", and discussed the potential problem of people using 3D printers to create guns. NSW and Victorian police obtained plans to create 3D printed guns and tested to see if they could fire, but the guns exploded during testing.[85]

In a 2013 report Samantha Bricknell from the Australian Institute of Criminology, Frederic Lemieux and Tim Prenzler compared mass shootings between America and Australia and found the "1996 NFA coincided within the cessation of mass shooting events" in Australia, and that there were reductions in America that were evident during the 1994-2004 US Federal Assault Weapon Ban.[3]

A 2015 journal article in the International Review of Law and Economics evaluated the effect of the NFA on overall crime, rather than just firearm deaths like other studies. Using the difference in differences identification approach, they found that after the NFA, "there were significant decreases in armed robbery and attempted murder relative to sexual assault".[86]

In 2016 four researchers evaluated the National Firearms Agreement after 20 years in relation to mental health. They said that the "NFA exemplifies how firearms regulation can prevent firearm mortality and injuries."[87]

In 2016 a study by Adam Lankford, associate professor of criminal justice, examined the links between public mass shootings and gun availability in various countries. He found that the restrictions in Australia were effective, concluding that "in the wake of these policies, Australia has yet to experience another public mass shooting."[88]

A 2017 oral presentation published in Injury Prevention examined the effect of the NFA on overall firearm mortality. They found that the NFA decreased firearm deaths by 61% and concluded that "Australian firearm regulations indeed contributed to a decline in firearm mortality."[89] After this study, these researchers were reported in the Journal of Experimental Criminology in connection with another study with Charles Branas at Columbia University which concluded; "Current evidence showing decreases in firearm mortality after the 1996 Australian national firearm law relies on an empirical model that may have limited ability to identify the true effects of the law." [90]

Major players in gun politics in Australia

Federal government

Until 1996, the federal government had little role in firearms law. Following the Port Arthur massacre, the Howard Government (1996–2007), with strong media and public support, introduced uniform gun laws with the cooperation of all the states, brought about through threats to Commonwealth funding arrangements. Then Prime Minister John Howard frequently referred to the United States to explain his opposition to civilian firearms ownership and use in Australia, stating that he did not want Australia to go "down the American path".[91][92][93] In one interview on Sydney radio station 2GB he said, "We will find any means we can to further restrict them because I hate guns... ordinary citizens should not have weapons. We do not want the American disease imported into Australia."[94] In 1995 Howard, as opposition leader, had expressed a desire to introduce restrictive gun laws.[95]

In Howard's autobiography Lazarus Rising: A Personal and Political Autobiography, Howard expressed his support for the anti-gun cause and his desire to introduce restrictive gun laws long before he became prime minister. In a television interview shortly before the 10th anniversary of the Port Arthur massacre, he reaffirmed his stance: "I did not want Australia to go down the American path. There are some things about America I admire and there are some things I don't. And one of the things I don't admire about America is their... slavish love of guns. They're evil". During the same television interview, Howard also stated that he saw the outpouring of grief in the aftermath of the Port Arthur massacre as "an opportunity to grab the moment and think about a fundamental change to gun laws in this country".[96]

Howard had strong public support in the immediate aftermath of the Port Arthur massacre, especially from those people who regularly voted against the Liberal Party. The Nationals had strong support from rural voters, some of whom were opposed to the government's moves towards gun control.

The National Firearms Agreement has had continuing support from both Labor and Coalition federal governments.[97][98]

Gun control organisations

The National Coalition for Gun Control (NCGC) had a high profile in the public debate up to and immediately after the Port Arthur massacre. Rebecca Peters, Roland Browne, Simon Chapman and Reverend Tim Costello[99] appeared in media reports and authored articles to support their aims.[100] In the aftermath of Port Arthur a number of public health bodies added their support to the NCGC.

In 1996, the NCGC had received the Australian Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission's Community Human Rights award.[101]

In 2003, Samantha Lee as chair of the NCGC was financed by a Churchill Fellowship to publish a paper[102] arguing that current handgun legislation is too loose, that police officers who are shooters have a conflict of interest, and that licensed private firearm ownership per se presents a threat to women and children.[103] In a late 2005 press release, Roland Browne as co-chair of the NCGC, advocated further restrictions on handguns.[104][105]

Pro-gun organisations

Shooting clubs have existed in Australia since the mid-19th century. They are mainly concerned with protecting the viability of hunting, collecting and target shooting sports. Australian shooters regard their sport as under permanent threat from increasingly restrictive legislation. They argue that they have been made scapegoats by politicians, the media, and anti-gun activists for the acts of criminals who generally use illegal firearms. Their researchers have found scant evidence that increasing restrictions have improved public safety, despite the high costs and severe regulatory barriers imposed on shooters in Australia.[106][107]

The largest organisation of firearms owners is the Sporting Shooters Association of Australia (SSAA) which was established in 1948, and as at 2015 had 175,000 members.[108] SSAA state branches lobby on local issues, while SSAA National addresses federal legislation and international issues. SSAA National has non-government organisation (NGO) status at the United Nations and is a founding member of The World Forum on the Future of Sport Shooting Activities (WFSA), which also has NGO status. SSAA National has a number of people working in research and lobbying roles. In 2008, they appointed journalist and media manager Tim Bannister as federal parliamentary lobbyist.[109] SSAA argues that there is no evidence that gun control restrictions in 1987, 1996 and 2002 had any impact on the already established trends.[110][111] Also, responding to Neill and Leigh, SSAA said that 93% of people replaced their seized firearms with at least one, to replace their surrendered firearms.[112]

For handguns, one major organisation in Australia is Pistol Australia.[113]

There are several other national bodies, such as Field and Game Australia, the National Rifle Association of Australia, the International Practical Shooting Confederation (IPSC), the Australian Clay Target Association and Target Rifle Australia. These national bodies with their state counterparts concentrate on a range of sporting and political issues ranging from Olympic type competition through to conservation activities.

The Combined Firearms Council of Victoria (CFCV) was created in late 2002 and has been very active in the debate in Victoria. The CFCV ran advertisements in the 2002 Victorian state election and made voting recommendations at the 2002 and 2006 Victorian state elections, supporting specific candidates rather than political parties. Four of the six Labor MPs elevated to the front bench after the 2002 Victorian election were supported by the CFCV. A Firearms Consultative Committee, established in 2005 in Victoria, led to several changes to firearms legislation that benefited handgun users and gun collectors.

The Shooters, Fishers and Farmers Party is a political party that started in New South Wales claims to be "the voice of hunters, shooters, fishers, rural and regional Australia and independent thinking Australians everywhere. Advocating for the politically incorrect, a voice of reason, science and conservation".[114] Its founder, John Tingle, served as an elected member of the upper house of New South Wales parliament, the Legislative Council, from 1995 until he retired in late 2006. As of March 2018 the party holds two seats in the NSW Legislative Council, and one seat in the Legislative Assembly.[115] In 2013 a Western Australian branch was formed and stood candidates in the state elections, winning a seat in the WA Legislative Council.[116] Shooters and Fishers candidates won two upper house seats in the 2014 Victorian state election.

The Firearm Owners United is a new gun rights group which in 2017 made its first financial contribution to a campaign during the Queensland state election, donating $1,000 to Pauline Hanson's One Nation party and Katter's Australian Party.[117]

Other parties

The One Nation party in 1997–98 briefly gained national prominence and had strong support from shooters. A number of minor political parties such as the Liberal Democratic Party of Australia (who are currently represented by David Leyonhjelm in the Australian Senate), Outdoor Recreation Party, Country Alliance and Katter's Australian Party (represented by Bob Katter in the House of Representatives)[118] have pro-shooter/pro-firearm platforms.

Public opinion

In 2015, Essential Research performed a poll regarding the support for Australia's gun laws. The demographic-normalised poll found that 6% of Australians thought the laws were "too strong", 40% thought "about right" and 45% thought "not strong enough".[6]

Essential Research repeated the poll a year later and found 6% thought the laws were too strong, 44% thought "about right" and 45% thought the laws were "not strong enough". It also found these views were consistent regardless of political party voting tendency for Labor, Coalition or Greens voters.[7][8][9]

In March 2018, Victorian police were set to be armed with military-style semi-automatic rifles to combat terrorism and the increase in gun-related crime.[119]

References

- ↑ "Firearms Act 1996 No 46, Part 2, Division 2, Section 12 - Genuine reasons for having a licence". NSW legislation. Retrieved 2018-02-24.

- 1 2 Large, Matthew; Nielssen, Olav. "Suicide in Australia: meta-analysis of rates and methods of suicide between 1988 and 2007" (PDF).

- 1 2 Lemieux, Frederic; Bricknell, Samantha; Prenzler, Tim (2015). "Mass shootings in Australia and the United States, 1981-2013". Journal of Criminological Research, Policy and Practice. 1 (3): 131–142. doi:10.1108/JCRPP-05-2015-0013. ISSN 2056-3841.

- 1 2 Lee, Wang-Sheng; Suardi, Sandy (2010). "The Australian Firearms Buyback and Its Effect on Gun Deaths". Contemporary Economic Policy. 28 (1): 65–79. doi:10.1111/j.1465-7287.2009.00165.x.

- 1 2 McPhedran, Samara; Baker, Jeanine (2011). "Mass shootings in Australia and New Zealand: A descriptive study of incidence". Justice Policy Journal. 8 (1). SSRN 2122854.

- 1 2 "Gun laws". Essential Research. 21 July 2015.

- 1 2 "Gun laws" (PDF). Essential Research. 1 November 2016.

- 1 2 Nick O'Malley, Sean Nicholls. "The killer quirk hiding in Australia's gun laws". Tenterfield Star.

- 1 2 Nick O'Malley, Sean Nicholls (7 October 2017). "The killer quirk hiding in Australia's gun laws". Advocacy against the 1996 gun laws puts shooters associations and parties considerably out of step with Australian popular opinion. In November last year a survey by Essential Research found 89 per cent of Australians thought our gun laws were either "about right" or "not strong enough" while just 6 per cent thought they were "too strong". Fairfax Media. SMH. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- ↑ "Legislative reforms". Australian Institute of Criminology. Australian Government. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- 1 2 Library of Congress: Firearms-Control Legislation and Policy: Australia

- ↑ Firearms Act 1996 (NSW).

- ↑ Weapons Prohibition Act 1998 (NSW).

- ↑ Firearms Act 1996 (Vic).

- ↑ Weapons Act 1990 (Qld).

- ↑ Firearms Act 1973 (WA).

- ↑ Firearms Act 2015 (SA).

- ↑ Firearms Act 1996 (Tas).

- ↑ Firearms Act (NT).

- ↑ Firearms Act 1996 (ACT).

- ↑ Customs (Prohibited Imports) Regulations 1956 (Cth).

- ↑ "Firearms Registry". NSW Police Force.

- ↑ http://www.ipsc.org.au/

- ↑ In ACT: Firearms Act 1996 (ACT) s 6(2)(a); In NSW: Firearms Act 1996 (NSW) s 6A(1); In Qld: Weapons Act 1990 (Qld) Schedule 2; In SA: for definition of 'antique firearm', see Firearms Act 2015 (SA) s 5, for exemption, see: Firearms Regulations 2017 (SA) r 44.

- ↑ In Vic: definition of an 'antique firearm', see Firearms Act 1996 (Vic) section 3, for licensing, see sections 22–23; In Tas: Firearms Act 1996 (Tas) s 28(1); In WA:Firearms Act 1973 (WA) s 16(1)(b).

- ↑ Victoria Police - Firearms - Eligibility Requirements

- 1 2 O'Malley, Nick (5 October 2017). "Australia's tough gun laws have been weakened by the states, new report". The Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax Media. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- 1 2 Wahlquist, Calla (4 October 2017). "Australian gun control audit finds states failed to fully comply with 1996 agreement". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ↑ Gothe-Snape, Jackson (12 October 2017). "Should kids have 'permits', 'licences' or no guns at all?". ABC News. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ↑ Christopher Halls 1974, Guns in Australia, Paul Hamlyn Pty Ltd Dee Why NSW

- ↑ McElhone, Megan --- "Now They're Extraordinary Powers': Firearms Prohibition Orders and Warrantless Search Powers in New South Wales" [2017] CICrimJust 5; (2017) 28(3) Current Issues in Criminal Justice 329

- ↑ Terror suspects slapped with strict gun ban

- 1 2 Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission, Illicit firearms in Australia

- ↑ Police gun data shows extent of private arsenals in suburban Australia

- ↑ Australia’s gun numbers climb: men who own several buy more than ever before

- ↑ Firearms carriage by police in Australia - Policies and issues, by Rick Sarre, Associate Professor, University of South Australia, 1996

- ↑ Mullen, Paul quoted in Hannon K 1997, "Copycats to Blame for Massacres Says Expert", Courier Mail, 4/3/1997

- ↑ Cantor, Mullen; Alpers (2000). "Mass homicide: the civil massacre". J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 28 (1): 55–63.

- ↑ Phillips, D. P. (1980). "Airplane accidents, murder, and the mass media: Towards a theory of imitation and suggestion". Social Forces. 58: 1001–1024. doi:10.1093/sf/58.4.1001.

- ↑ Cialdini, Robert 2001. Influence: Science and Practice 4th Ed. Allyn and Bacon, pp. 121–130.

- ↑ Cramer, C 1993. Ethical problems of mass murder coverage in the mass media. Journal of Mass Media Ethics 9.

- ↑ Duncan Chappell (2004). "Prevention of Violent Crime: The Work of the National Committee on Violence" (PDF). Australian Institute of Criminology. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ↑ John Howard. "I Went After Guns. Obama Can, Too". New York Times. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ↑ Guerrera, Orietta (28 April 2006). "Anger lingers among those who lost their firearms". The Age. Melbourne.

- ↑ Nicholson (17 June 1996). "'E's carrying on like some kind of Nazi". The Australian.

- ↑ Dore, Christopher (6–27 May 1997). "The Smoking Guns Buyback". The Weekend Australian.

- ↑ Reardon, Dave (10 June 1996). "Progun Liberals Recruit for Party". The West Australian.

- ↑ Atkins, Dennis (26 June 1996). "Libs on Alert for Pro-Gun Infiltration". The Brisbane Courier Mail.

- ↑ "Shooter Rejected". Border Mail – Albury. 22 February 1997.

- ↑ "The gun buy back scheme" (PDF). Australian Auditor-General. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 January 2016. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ↑ Smith-Spark, Laura (2015-06-19). "This is what happened when Australia introduced tight gun controls". CNN. Retrieved 2016-01-07.

- ↑ Topsfield, Jewel (18 June 2004). "Monash gunman not guilty". Fairfax Media. The Age. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ↑ Hudson, Phillip (1 February 2004). "State's gun owners reap $21m". The Age.

- ↑ "Sydney siege: Tony Abbott launches urgent joint inquiry". The Australian. 17 December 2014. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ↑ Coultan, Mark (28 August 2015). "New firearms restrictions and bail laws for NSW after Martin Place siege". NSW Deputy Premier Troy Grant said that penalties for firearm offences will be increased, with a new offence of possession of a stolen firearm, which will carry a maximum penalty of 14 years jail. There will also be a ban on possessing blueprints for firearms capable of being used by 3D printers, as well as unlicensed milling machines. News Corp. The Australian. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ↑ "Gun Amnesty goes Gangbusters". Marketing. Niche Media. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- 1 2 Minister for Justice Michael Keenan (16 June 2017). "National Firearms Amnesty starts on July 1" (Press release). Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ↑ "National gun amnesty called amid 'deteriorating national security environment'". Sydney Morning Herald. AAP. 16 June 2017. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ↑ "Terms of Reference for the 2017 National Firearms Amnesty in Victoria". Victoria Police. 19 July 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ↑ "Australians hand over 51,000 firearms in illegal weapons amnesty". 6 October 2017.

- ↑ 7111;, corporateName=Commonwealth Parliament; address=Parliament House, Canberra, ACT, 2600; contact=+61 2 6277. "National Firearms Amnesty". www.aph.gov.au.

- ↑ Jenny Mouzos; Catherine Rushforth (November 2003). "Firearm related deaths in Australia, 1991-2001". Australian Institute of Criminology. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ↑ Australian Bureau of Statistics (2 December 2003). "3309.0.55.001 – Suicides: Recent Trends, Australia, 1992 to 2002" (PDF).

- ↑ Australian Bureau of Statistics (14 March 2007). "3309 Suicides Australia 2005" (PDF).

- ↑ Bricknell, S (2008). Firearm theft in Australia 2006–07 (PDF). Australian Institute of Criminology. ISBN 978-1-921532-05-4. ISSN 1445-7261.

- ↑ "Gun Runners". 4 Corners. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 15 May 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ↑ Mouzos, Jenny (2000). Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice No. 151: The licensing and registration status of firearms used in homicide (PDF). Australian Institute of Criminology. ISBN 0-642-24162-7. ISSN 0817-8542.

- ↑ Mouzos, Jenny (2002). Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice No. 230: Firearms theft in Australia (PDF). Australian Institute of Criminology. ISBN 0-642-24265-8. ISSN 0817-8542.

- ↑ Hemenway, David; Vriniotis, Mary (Spring 2011). "The Australian Gun Buyback" (PDF). Bulletins (4). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 May 2013.

- ↑ Harding, Richard (1981). Firearms and Violence in Australian Life. Perth: University of Western Australia Press. p. 119. ISBN 0 85564 190 8.

- ↑ Newton, George; Zimring, Franklin (1968). "Firearms and Violence in American Life" (PDF). Report Submitted to the National Commission on the Causes & Prevention of Violence. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ Harding, Richard. Gun law reform in New South Wales:Better late than never (PDF) (Report). p. 32.

- ↑ Mouzos, Jenny (June 2002). Firearms Theft in Australia (PDF) (230 ed.). Australian Institute of Criminology. ISBN 0 642 24265 8. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ↑ Ozanne-Smith, J (2004). "Firearm related deaths: the impact of regulatory reform". Injury Prevention. 10 (5): 280–286. doi:10.1136/ip.2003.004150. ISSN 1353-8047. PMC 1730132.

- ↑ Baker, Jeanine; McPhedran, Samara (18 October 2006). "Gun Laws and Sudden Death: Did the Australian Firearms Legislation of 1996 Make a Difference?". British Journal of Criminology. 47 (3): 455–469. doi:10.1093/bjc/azl084.

- ↑ McPhedran, Samara; Baker, Jeanine (2012). "Suicide Prevention and Method Restriction: Evaluating the Impact of Limiting Access to Lethal Means among Young Australians". Archives of Suicide Research. 16 (2): 135–146. doi:10.1080/13811118.2012.667330. PMID 22551044.

- ↑ Interview with Damien Carrick, The Law Report, ABC Radio National, 31 October 2006

- ↑ Don Weatherburn (16 October 2006). "Study No Excuse to shoot down the law". The Sydney Morning Herald. John Fairfax Holdings. Retrieved 2006-11-21.

- ↑ in Wainwright, Robert. "Gun laws fall short in war on crime", The Sydney Morning Herald, 29 October 2005. Accessed 10 August 2010

- ↑ Weatherburn, Don. "Statistics and gun laws", The Sydney Morning Herald, 1 November 2005. Accessed 10 August 2010

- ↑ Chapman, Simon; P Alpers, P; Agho, K; Jones, M (2006). "Australia's 1996 gun law reforms: faster falls in firearm deaths, firearm suicides, and a decade without mass shootings". Injury Prevention. 12 (6): 365–72. doi:10.1136/ip.2006.013714. PMC 2704353. PMID 17170183.

- ↑ Tait, Gordon; Carpenter, Belinda (2009). "Firearm suicide in Queensland". Journal of Sociology. 46 (1): 83–98. doi:10.1177/1440783309337673. ISSN 1440-7833.

- ↑ Klieve, Helen; Barnes, Michael; De Leo, Diego (2008). "Controlling firearms use in Australia: has the 1996 gun law reform produced the decrease in rates of suicide with this method?". Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 44 (4): 285–292. doi:10.1007/s00127-008-0435-9. ISSN 0933-7954.

- ↑ Leigh, Andrew; Neill, Christine (2010). "Do Gun Buybacks Save Lives? Evidence from Panel Data". Am Law Econ Rev. 12 (2): 462–508. doi:10.1093/aler/ahq013.

- ↑ Jabour, Bridie (13 October 2014). "Australia has 260,000 illegal firearms in circulation, inquiry told" – via The Guardian.

- ↑ Taylor, Benjamin; Li, Jing (2015). "Do fewer guns lead to less crime? Evidence from Australia". International Review of Law and Economics. 42: 72–78. doi:10.1016/j.irle.2015.01.002. ISSN 0144-8188.

- ↑ Dudley, Michael J; Rosen, Alan; Alpers, Philip A; Peters, Rebecca (2016). "The Port Arthur massacre and the National Firearms Agreement: 20 years on, what are the lessons?". The Medical Journal of Australia. 204 (10): 381–383. doi:10.5694/mja16.00293. ISSN 0025-729X.

- ↑ Lankford, Adam (2016). "Public Mass Shooters and Firearms: A Cross-National Study of 171 Countries". Violence and Victims. 31 (2): 187–199. doi:10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-15-00093. ISSN 0886-6708.

- ↑ Andreyeva, Elena; Ukert, Benjamin (2017). "11 Do firearm regulations work? evidence from the australian national firearms agreement": A4.2–A4. doi:10.1136/injuryprev-2017-042560.11.

- ↑ Ukert, Benjamin; Andreyeva, Elena; Branas, Charles C. (29 October 2017). "Time series robustness checks to test the effects of the 1996 Australian firearm law on cause-specific mortality". Journal of Experimental Criminology: 1–14. doi:10.1007/s11292-017-9313-3 – via link.springer.com.

- ↑ Los Angeles Times Special Report Archived 25 March 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Australia's Answer to Carnage: a Strict Law, Jeff Brazil and Steve Berry, 27 August 1997.

- ↑ Radio 3AW Archived 24 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine. John Howard radio interview, 20 March 1998.

- ↑ John Howard's address to the Council of Small Business Organisations of Australia, Canberra, 28 May 2002.

- ↑ "TRANSCRIPT OF THE PRIME MINISTER THE HON JOHN HOWARD MP INTERVIEW WITH PHILIP CLARK, RADIO 2GB". That is one of the difficulties and we will find any means we can to further restrict them because I hate guns. I don';t think people should have guns unless they';re police or in the military or in the security industry. There is no earthly reason for people to have…ordinary citizens should not have weapons. We do not want the American disease imported into Australia. Australian Government. Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. 17 April 2002. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ↑ "The Role of Government: John Howard 1995 Headland Speech". Let me say that in the ebbing and flowing debate on the availability of weapons, I am firmly on the side of those who believe that it would be a cardinal tragedy if Australia did not learn the bitter lessons of the United States regarding guns. I have no doubt that the horrific homicide level in the United States is directly related to the plentiful supply of guns. How else does one explain the simple fact that in the United States the murder rate is 10 per 100,000, against one per 100,000 in England and Wales and 2.0 in Australia. Whilst making proper allowance for legitimate sporting and recreational activities and the proper needs of our rural community, every effort should be made to limit the carrying of guns in Australia. AUSTRALIANPOLITICS.COM. 6 June 1995. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ↑ "Interview with Karl Stefanovic Today Show, Channel Nine". Oh I recall that very vividly. I recall the extraordinary outpouring of amazement and grief in the country and I knew out of that there was an opportunity to grab the moment and to bring about a fundamental change in gun laws in this country. I did not want Australia to go down the American path. There are some things about America I admire, there are some things I don't and one of the things I don't admire about America is an almost drooling, slavish love of guns. I think they're evil. Australian Government. Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. 1 March 2006. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ↑ SSAA National (November 2007). "Australian Labor Party statement". Capital News.

- ↑ SSAA National (August 2010). "Australian Labor Party statement".

- ↑ Hudson, Phillip (25 October 2002). "Handgun curbs on the way". Melbourne: The Age.

- ↑ Peters, Rebecca (28 April 2006). "Nations disarm as laws tighten (opinion)". The Australian. Archived from the original on 7 May 2006.

- ↑ "1996 Human Rights Medal and Awards Winners". Australian Human Rights Commission. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ↑ Lee, Samantha (2003). "Handguns: Laws, Violence and Crime in Australia" (PDF). Churchill Fellowship Research Paper.

- ↑ Liverani, Mary Rose (July 2005). "Maintaining a watching brief on gun control – Activist adds law studies to her arsenal". Journal of the Law Society of New South Wales.

- ↑ Coorey, Phillip (27 April 2006). "Howard's sights set on reducing gun ownership". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ↑ Interview with Barney Porter, ABC radio, 27 April 2006

- ↑ "SSAA Research Archive". Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- ↑ "Ten years after the National Firearms Agreement of 1996 Australian Shooter". June 2006. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- ↑ SSAA National (October 2013). "SSAA National membership figures". About us. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ↑ SSAA National (June 2008). "Capital News".

- ↑ Trouble in Paradise Archived 27 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine., SSAA presentation at Goroka Gun Summit, 2005

- ↑ The impact of gun-control laws called into question Archived 23 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine., SSAA media release, November 2004

- ↑ "Prevention, not gun buy-backs, key to suicide reduction". Sporting Shooters Association of Australia. Archived from the original on 28 November 2010. Retrieved 2010-09-01.

- ↑ "Pistol Australia". Pistol Australia. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ↑ Shooters Party website. Accessed 12 October 2013.

- ↑ "Members of NSW Parliament: Shooters, Fishers and Farmers Party". Archived from the original on 26 March 2018.

- ↑ "Current Members of the Legislative Council". Parliament.WA.gov.au. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ↑ "Gun lobby group that helped bankroll One Nation linked to anti-Islam group". TheGuardian.com. Archived from the original on 15 March 2018.

- ↑ "Issues: Firearm Policy". Archived from the original on 26 August 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- ↑ Tomazin, Farrah; Houston, Cameron (28 March 2018). "Victoria Police to get military-style semi-automatic guns". The Age. Fairfax Media. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

Notes

- ↑ Semi-automatic rifles are permitted in New Zealand with the standard "category A" New Zealand firearm license provided the gun is not a military-style semi-automatic which among other things means it must have a magazine capacity of at most 7 rounds.

External links

- Reynolds, Christopher. "Issue Management and the Australian Gun Debate: A review of the media salience and issue management following the Tasmanian massacre of 1996". Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- Australian Institute of Criminology report, 1999 Firearm-related violence: the impact of the Nationwide Agreement on Firearms