Gladius

| Gladius | |

|---|---|

Replica pseudo-Pompeii gladius | |

| Type | Sword |

| Place of origin | Ancient Rome as gladius |

| Service history | |

| In service | 3rd century BC–3rd century AD |

| Used by | Roman foot soldiers during wars |

| Wars | Roman Republic and Roman Empire |

| Specifications | |

| Weight | 0.7–1 kg (1.5–2.2 lb) |

| Length | 60–85 cm (24–33 in) |

| Blade length | 45–68 cm (18–27 in) |

| Width | 5–7 cm (2.0–2.8 in) |

|

| |

| Blade type | steel of varying degrees of carbon content, pointed, double-edged |

| Hilt type | Wood, bronze or ivory |

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Military of ancient Rome |

|---|

|

|

Gladius (/ˈɡleɪdiəs/;[1] Classical Latin: [ˈɡladiʊs]) was one Latin word for sword, and is used to represent the primary sword of Ancient Roman foot soldiers. Early ancient Roman swords were similar to those of the Greeks, called xiphos. From the 3rd century BC, however, the Romans adopted swords similar to those used by the Celtiberians and others during the early part of the conquest of Hispania. This sword was known as the gladius hispaniensis, or "Hispanic sword".[2]

A fully equipped Roman legionary after the reforms of Gaius Marius was armed with a shield (scutum), one or two javelins (pila), a sword (gladius), often a dagger (pugio), and, perhaps in the later empire period, darts (plumbatae). Conventionally, soldiers threw pilae to disable the enemy's shields and disrupt enemy formations before engaging in close combat, for which they drew the gladius. A soldier generally led with the shield and thrust with the sword. All gladius types appear to have been suitable for cutting and chopping as well as thrusting.[3]

Etymology

Gladius is a Latin masculine second declension noun. Its (nominative and vocative) plural is gladiī. However, gladius in Latin refers to any sword, not specifically the modern definition of a gladius. The word appears in literature as early as the plays of Plautus (Casina, Rudens).

Gladius is generally believed to be a Celtic loan in Latin (perhaps via an Etruscan intermediary), derived from ancient Celtic *kladi(b)os or *kladimos "sword" (whence modern Welsh cleddyf "sword", modern Breton klezeff, Old Irish claideb/Modern Irish claidheamh [itself perhaps a loan from Welsh]; the root of the word may survive in the Old Irish verb claidid "digs, excavates" and anciently attested in the Gallo-Brittonic place name element cladia/clado "ditch, trench, valley hollow").[4][5][6][7][8]

Modern English words derived from gladius include gladiator ("swordsman") and gladiolus ("little sword", from the diminutive form of gladius), a flowering plant with sword-shaped leaves.

Predecessors and origins

-Segunda_Edad_del_Hierro.jpg)

According to Livy and Polybius, Celtiberian mercenaries for Hannibal at the Battle of Cannae wielded short swords that excelled at both slashing and thrusting.[9] Roman military would have adopted this design even before the end of the war, calling it gladius hispaniensis in Latin and iberiké machaira in Greek.[9] This weapon replaced the previous Roman sword, which would have been based on the Greek xiphos.[9]

Later, Livy[10] relates the story of Titus Manlius Torquatus accepting a challenge to a single combat by a large Gallic soldier at a bridge over the Anio river, where the Gauls and the Romans were encamped on opposite sides. Manlius strapped on the "Hispanic sword" (gladius Hispanus).[11] During the combat he thrust twice with it under the shield of the Gaul, dealing fatal blows to the abdomen. He then removed the Gaul's torc and placed it around his own neck, hence the name, torquatus.[12]

The combat occurred during the consulships of C. Sulpicius Peticus and C. Licinius Stolo—i.e., about 361 BC, long before the Punic Wars, but during the frontier wars with the Gauls (366-341 BC). One theory proposes the borrowing of the word gladius from *kladi- during this period, relying on the principle that k often became g in Latin. Ennius attests the word. Gladius may have replaced ensis, which in the literary periods was used mainly by poets.[13]

The exact origin of the gladius Hispanus is disputed. While it is likely that it descended ultimately from Celtic swords of the La Tene and Hallstat periods, no one knows if it came to the Romans through Celtiberian troops of the Punic Wars, or through Gallic troops of the Gallic Wars.

Arguments for the Celtiberian source of the weapon have been reinforced in recent decades by discovery of early Roman gladii that seem to highlight that they were copies of Celtiberian models. The weapon developed in Iberia after La Tène I models, which were adapted to traditional Celtiberian techniques during the late 4th and early 3rd centuries BC.[14] These weapons are quite original in their design, so that they cannot be confused with Gallic types.

Manufacture

By the time of the Roman Republic, which flourished during the Iron Age, the classical world was well-acquainted with steel and the steel-making process. Pure iron is relatively soft, but pure iron is never found in nature. Natural iron ore contains various impurities in solid solution, which harden the reduced metal by producing irregular-shaped metallic crystals. The gladius was generally made out of steel.

In Roman times, workers reduced ore in a bloomery furnace. The resulting pieces were called blooms,[15] which they further worked to remove slag inclusions from the porous surface.

A recent metallurgical study of two Etrurian swords, one in the form of a Greek kopis from 7th century BC Vetulonia, the other in the form of a gladius Hispaniensis from 4th century BC Chiusa, gives insight concerning the manufacture of Roman swords.[16] The Chiusa sword comes from Romanized etruria; thus, regardless of the names of the forms (which the authors do not identify), the authors believe the process was continuous from the Etruscans to the Romans.

The Vetulonian sword was crafted by the pattern welding process from five blooms reduced at a temperature of 1163 °C. Five strips of varying carbon content were created. A central core of the sword contained the highest: 0.15–0.25% carbon. On its edges were placed four strips of low-carbon steel, 0.05–0.07%, and the whole thing was welded together by forging on the pattern of hammer blows. A blow increased the temperature sufficiently to produce a friction weld at that spot. Forging continued until the steel was cold, producing some central annealing. The sword was 58 cm (23 in) long.[16]

The Chiusian sword was created from a single bloom by forging from a temperature of 1237 °C. The carbon content increased from 0.05–0.08% at the back side of the sword to 0.35–0.4% on the blade, from which the authors deduce that some form of carburization may have been used. The sword was 40 cm (16 in) long and was characterized by a wasp-waist close to the hilt.

Romans continued to forge swords, both as composites and from single pieces. Inclusions of sand and rust weakened the two swords in the study, and no doubt limited the strength of swords during the Roman period.

Description

The word gladius acquired a general meaning as any type of sword. This use appears as early as the 1st century AD in the Biography of Alexander the Great by Quintus Curtius Rufus.[17] The republican authors, however, appear to mean a specific type of sword, which is now known from archaeology to have had variants.

Gladii were two-edged for cutting and had a tapered point for stabbing during thrusting. A solid grip was provided by a knobbed hilt added on, possibly with ridges for the fingers. Blade strength was achieved by welding together strips, in which case the sword had a channel down the center, or by fashioning a single piece of high-carbon steel, rhomboidal in cross-section. The owner's name was often engraved or punched on the blade.

The hilt of a Roman sword was the capulus. It was often ornate, especially the sword-hilts of officers and dignitaries.

Stabbing was a very efficient technique, as stabbing wounds, especially in the abdominal area, were almost always deadly.[18] However, the gladius in some circumstances was used for cutting or slashing, as is indicated by Livy's account of the Macedonian Wars, wherein the Macedonian soldiers were horrified to see dismembered bodies.[19]

Though the primary infantry attack was thrusting at stomach height, they were trained to take any advantage, such as slashing at kneecaps beneath the shield wall.

The gladius was sheathed in a scabbard mounted on a belt or shoulder strap, some say on the right, some say on the left. Some say the soldier reached across his body to draw it, and others claim that the position of the shield made this method of drawing impossible. A centurion wore it on the opposite side as a mark of distinction.[20]

Towards the end of the 2nd century AD and during the 3rd century the spatha gradually took the place of the gladius in the Roman legions.

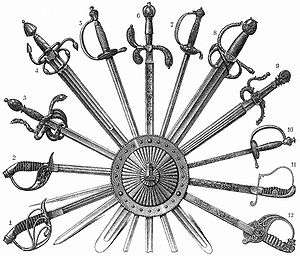

Types

Several different designs were used; among collectors and historical reenactors, the three primary kinds are known as the Mainz gladius, the Fulham gladius, and the Pompeii gladius (these names refer to where or how the canonical example was found). More recent archaeological finds have uncovered an earlier version, the gladius Hispaniensis.

The differences between these varieties are subtle. The original Hispanic sword, which was used during the republic, had a slight "wasp-waist" or "leaf-blade" curvature. The Mainz variety came into use on the frontier in the early empire. It kept the curvature, but shortened and widened the blade and made the point triangular. At home, the less battle-effective Pompeii version came into use. It eliminated the curvature, lengthened the blade, and diminished the point. The Fulham was a compromise, with straight edges and a long point.[21]

Descriptions of the main types follow:

- Gladius Hispaniensis: Used from around 216 BC until 20 BC. Blade length ~60–68 cm (24–27 in). Sword length ~75–85 cm (30–33 in). Sword width ~5 cm (2.0 in). This was the largest and heaviest of the gladii. Earliest and longest blade of the gladii, pronounced leaf-shape compared to the other forms. Max weight ~1 kg (2.2 lb) for the largest versions, most likely a standard example would weigh ~900 g (2.0 lb) (wooden hilt).

- Mainz gladius: Mainz was founded as the Roman permanent camp of Moguntiacum probably in 13 BC. This large camp provided a population base for the growing city around it. Sword manufacture probably began in the camp and was continued in the city; for example, Gaius Gentilius Victor, a veteran of Legio XXII, used his discharge bonus on retirement to set up a business as a negotiator gladiarius, a manufacturer and dealer of arms.[22] Swords made at Mainz were sold extensively to the north. The Mainz variety is characterized by a slight waist running the length of the blade and a long point. Blade length ~50–55 cm (20–22 in). Sword length ~65–70 cm (26–28 in). Blade width ~7 cm (2.8 in). Sword weight ~800 g (1.8 lb) (wooden hilt).

- Fulham gladius or Mainz-Fulham gladius: The sword that gave the name to the type was dredged from the Thames near Fulham, and must therefore date to after the Roman occupation of Britain began—after the invasion of Aulus Plautius in 43 AD. Romans used it until the end of the same century. It is considered the conjunction point between Mainz and Pompei. Some consider it an evolution or the same as the Mainz type. The blade is slightly narrower than the Mainz variety. The main difference is the triangular tip. Blade length ~50–55 cm (20–22 in). Sword length ~65–70 cm (26–28 in). Blade width ~6 cm (2.4 in). Sword weight ~700 g (1.5 lb) (wooden hilt).

- Pompeii gladius (or Pompeianus or Pompei): Named by modern historians after the Roman town of Pompeii, this gladius was by far the most popular one. Four instances of the sword type were found in Pompeii, with others turning up elsewhere. The sword has parallel cutting edges and a triangular tip. This is the shortest of the gladii. It is often confused with the spatha, which was a longer, slashing weapon used initially by mounted auxilia. Over the years, the Pompeii got longer, and these later versions are called as semi-spathas. Blade length ~45–50 cm (18–20 in). Sword length ~60–65 cm (24–26 in). Blade width ~5 cm (2.0 in). Sword weight ~700 g (1.5 lb) (wooden hilt).

The Mainz and the Pompeii are the two main classification types and served side by side for many years and it was not uncommon to find 4th century legionaries carrying the earlier model.

See also

Notes

- ↑ "gladius". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Penrose, Jane (2008). Rome and Her Enemies: An Empire Created and Destroyed by War. Osprey Publishing. pp. 121–122. ISBN 1-84603-336-5.

- ↑ Vegetius De Re Militari 2.15

- ↑ McCone, Kim, "Greek Κελτός and Γαλάτης, Latin Gallus 'Gaul', in: Die Sprache 46, 2006, p. 106

- ↑ Schrijver, Peter, The Reflexes of the Proto-Indo-European Laryngeals in Latin, Rodopi, 1991, p. 174.

- ↑ Delamarre, Xavier, Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise, Errance, 2003 (2nd ed.), p. 118.

- ↑ Schmidt, Karl Horst, 'Keltisches Wortgut im Lateinischen', in: Glotta 44 (1967), p. 159.

- ↑ Koch, Celtic Culture, ABC-CLIO, 2006, p. 215

- 1 2 3 Quesada Sanz, F. "Gladius hispaniensis: an archaeological view from Iberia" (PDF). Retrieved August 10, 2018.

- ↑ Livius, Titus. "The History of Rome, Vol. II". 7.10. Archived from the original on August 30, 2002. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ↑ Livy's term (link). Most authors use the term gladius Hispaniensis but a few use Livy's term, Hispanus. Both are adjectives of the same meaning, that is, they refer to Hispania, or the Iberian Peninsula.

- ↑ Livy 1982, p. 109

- ↑ This theory is stated in Note 80, Page 191, of faculty dissertation RUNIC INSCRIPTIONS IN OR FROM THE NETHERLANDS by Tineke Looijenga, University of Groningen.

- ↑ Archived October 2, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ blooms

- 1 2 Nicodemi, Walter; Mapelli, Carlo; Venturini, Roberto; Riva, Riccardo (2005). "Metallurgical Investigations on Two Sword Blades of 7th and 3rd Century B.C. Found in Central Italy". ISIJ International. 45 (9): 1358–1367. doi:10.2355/isijinternational.45.1358.

- ↑ "Copidas vocabant gladios leviter curvatos, falcibus similes: "They called their lightly curved, sickle-like swords (gladios) 'copides'."

- ↑ Vegetius, De Re Militari, Book I Archived July 16, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.: "a stab, though it penetrates but two inches, is generally fatal."

- ↑ Histories, Book 31, Chapter 34.

- ↑ See under gladius Archived October 4, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. in Seyffert, Dictionary of Classical Antiquities.

- ↑ Archived October 25, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Verboven, Koenraad S. (2007). "Good for business: The roman army and the emergence of a 'business class' in the northwestern provinces of the roman empire (1st century BCE–3rd century CE)". In Blois, Lukas; Lo Cascio, Elio. The Impact of the Roman Army (200 B.C. – A.D. 476): Economic, Social, Political, Religious and Cultural Aspects (PDF). Brill. pp. 295–314. doi:10.1163/ej.9789004160446.i-589.44. ISBN 9789047430391. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 10, 2007.

^ Please note that this is only true for the nominative case; For more information, see the Latin declension page.

References

- Significant Contributions in the Study of European Arms and Armor, bibliography by the Arms and Armor Society of America.

- Armamentarium: subject bibliographies: swords

- John William Humphrey, John Peter Oleson, Andrew Neil Sherwood, Greek and Roman Technology: a sourcebook

- Livius, Titus (known as Livy) (1982). Rome and Italy: Books VI-X of the History of Rome from its Foundation, translated by Betty Radice. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-044388-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gladii. |

The articles in the links below often differ both in theory and in detail. They should not necessarily be understood as fully professional articles but should be appreciated for their presentational value.

Pictures of ancient swords

- Roman Military Equipment at the Roman Numismatic Gallery (romancoins.info)

Reenactments, reconstructions, experimental archaeology

- Legio IX Hispana: photos of historical reconstructionists drawing and holding gladii.

- "Legio XX Gladius".

- "Legio XXIV Gladiator page".

- "The Roman Legionary and His Equipment in The First Century AD: An Assessment of the findings of The Ermine Street Guard".

Articles on the history or manufacture of the sword

- Iron of the Empire: The History and Development of the Roman Gladius (myArmoury.com article)

- Janet Lang, Study of the Metallography of Some Roman Swords

- Niko Silvester, FROM RAPIER TO LANGSAX: Sword Structure in the British Isles in the Bronze and Iron Ages

- Richard F. Burton, THE SWORD AMONGST THE BARBARIANS (EARLY ROMAN EMPIRE).

- Taylor, Michael J. "Sword of the Republic: The Gladius Hispaniensis." Classic Arms and Militaria Magazine. October 2011.