Scutum (shield)

The Scutum (English: /ˈskuːtəm/; plural scuta; Classical Latin: [ˈskuːtũː]) was a type of shield used among Italic peoples in antiquity, and then by the army of ancient Rome starting about the fourth century BC. The Romans adopted it when they switched from the military formation of the hoplite phalanx of the Greeks to the formation with maniples. In the former, the soldiers carried a round shield, which the Romans called clipeus. In the latter, they used the scutum, which was a larger shield. Originally it was an oblong and convex shield. By the first century BC it had developed into the rectangular, semi-cylindrical shield that is popularly associated with the scutum in modern times. This was not the only shield the Romans used; Roman shields were of varying types depending on the role of the soldier who carried it. Oval, circular and rectangular shields were used throughout Roman history.

History

.jpg)

In the early days of Ancient Rome (from the late regal period to the first part of the early republican period) Roman soldiers wore clipeus, which was like the aspides (ἀσπίδες), a small round shield used in the Greek hoplite phalanx. The hoplites were heavy infantrymen who originally wore a bronze shield and helmet. The phalanx was a compact, rectangular mass military formation. The soldiers lined up in very tight ranks in a formation which was eight lines deep. The phalanx advanced in unison, which encouraged cohesion among the troops. It formed a shield wall and a mass of spears pointing towards the enemy. Its compactness provided a thrusting force which had a great impact on the enemy and made frontal assaults against it very difficult. However, it also had its drawbacks. It worked only if the soldiers kept the formation tight and had the discipline needed to keep its compactness in the thick of the battle. It was a rigid form of fighting and its maneuverability was limited. The shields being small provided less protection. However, their smaller size afforded more mobility. Their round shape enabled the soldiers to interlock them to hold the line together.

Sometime in the early fourth century BC, the Romans changed their military tactics from the hoplite phalanx to the manipular formation, which was much more flexible. This involved a change in military equipment. The scutum replaced the clipeus. Some ancient writers thought that the Romans had adopted the maniples and the scutum when they fought against the Samnites in the first or second Samnite War (343-341 BC, 327-304 BC).[1] However, Livy did not mention the scutum being a Samnite shield and wrote that the oblong shield and the manipular formation were introduced in the early fourth century BC, before the conflicts between the Romans and the Samnites.[2] Plutarch mentioned the use of the long shield in a battle which took place in 366 BC.[3] Couissin notes archaeological evidence shows that the scutum was in general use among Italic peoples long before the Samnite Wars and argues that it was not obtained from the Samnites.[4] In some parts of Italy the scutum had been used since pre-historical times.[5]

Polybius gave a description of the early second century scutum:[6]

The Roman panoply consists firstly of a shield (scutum), the convex surface of which measures two and a half feet in width and four feet in length, the thickness at the rim being a palm's breadth. It is made of two planks glued together, the outer surface being then covered first with canvas and then with calf-skin. Its upper and lower rims are strengthened by an iron edging which protects it from descending blows and from injury when rested on the ground. It also has an iron boss (umbo) fixed to it which turns aside the most formidable blows of stones, pikes, and heavy missiles in general.

The oval scutum is depicted on the Altar of Domitius Ahenobarbus in Rome, the Aemilius Paullus monument at Delphi, and there is an actual example found at Kasr el-Harit in Egypt. Gradually the scutum evolved into the rectangular (or sub-rectangular) type of the early Roman Empire.

By the end of the 3rd century the rectangular scutum seems to have disappeared. Fourth century archaeological finds (especially from the fortress of Dura-Europos) indicate the subsequent use of oval or round shields which were not semi-cylindrical but were either dished (bowl-shaped) or flat. Roman artwork from the end of the 3rd century till the end of Antiquity show soldiers wielding oval or round shields.

The word "scutum" survived the Roman Empire and entered the military vocabulary of the Byzantine Empire. Even in the 11th century, the Byzantines called their armoured soldiers skutatoi (Grk. σκυτατοί).

Structure

The scutum was a 10-kilogram (22 lb)[7] large rectangle curved shield made from three sheets of wood glued together and covered with canvas and leather, usually with a spindle shaped boss along the vertical length of the shield. The best surviving example, from Dura-Europos in Syria, was 105.5 centimetres (41.5 in) high, 41 centimetres (16 in) across, and 30 centimetres (12 in) deep (due to its semicylindrical nature), with a thickness of 5-6mm.[8][9] It was likely well made and extremely sturdy.

Advantages and disadvantages

The scutum is light enough to be held in one hand and its large height and width covered the entire wielder, making him very unlikely to get hit by missile fire and in hand-to-hand combat. The metal boss, or umbo, in the centre of the scutum also made it an auxiliary punching weapon as well. Its composite construction meant that early versions of the scutum could fail from a heavy cutting or piercing blow, which was experienced in the Roman Campaigns against Carthage and Dacia where the Falcata and Falx could easily penetrate and rip through the scutum. The effects of these weapons prompted design changes that made the scutum more resilient such as thicker planks and metal edges.

Compared to the earlier aspis, which it replaced, the aspis was heavier and provided less protective coverage than the scutum but was much more durable.

Combat uses

According to Polybius, the scutum gave Roman soldiers an edge over their Carthaginian enemies during the Punic Wars:[10] "Their arms also give the men both protection and confidence owing to the size of the shield."

The Roman writer Suetonius recorded an anecdote of the heroic centurion Cassius Scaeva, who fought under Caesar in the Battle of Dyrrachium:[11]

with one eye gone, his thigh and shoulder wounded, and his shield bored through [with arrows] in a hundred and twenty places, [he] continued to guard the gate of a fortress put in his charge... [he] boarded the ship and drove the enemy before him with the boss of his shield.

The Roman writer Cassius Dio in his Roman History described Roman against Roman in the Battle of Philippi: "For a long time there was pushing of shield against shield and thrusting with the sword, as they were at first cautiously looking for a chance to wound others without being wounded themselves."

The shape of the scutum allowed packed formations of legionaries to overlap their shields to provide an effective barrier against missiles. The most novel (and specialised, for it afforded negligible protection against other attacks) use was the testudo (Latin for "tortoise"), which added legionaries holding shields from above to protect against descending missiles (such as arrows or objects thrown by defenders on walls).

Dio gives an account of a testudo put to good use by Marc Antony's men while on campaign in Armenia:

One day, when they fell into an ambush and were being struck by dense showers of arrows, [the legionaries] suddenly formed the testudo by joining their shields, and rested their left knees on the ground. The barbarians... threw aside their bows, leaped from their horses, and drawing their daggers, came up close to put an end to them. At this the Romans sprang to their feet, extended their battle-line... and confronting the foe face to face, fell upon them... and cut down great numbers.

However, the testudo was not invincible, as Dio also gives an account of a Roman shield array being defeated by Parthian knights and horse archers at the Battle of Carrhae:

For if [the legionaries] decided to lock shields for the purpose of avoiding the arrows by the closeness of their array, the [knights] were upon them with a rush, striking down some, and at least scattering the others; and if they extended their ranks to avoid this, they would be struck with the arrows.

Special uses

Cassius Dio describes scuta being used to aid an ambush:

Now Pompey was anxious to lead Oroeses into conflict before he should find out the number of the Romans, for fear that when he learned it he might retreat... he kept the rest behind... in a kneeling position and covered with their shields, causing them to remain motionless, so that Orestes should not ascertain their presence until he came to close quarters.

Dio also notes the use of the scutum as a tool of psychological warfare during the capture of Syracuse:

Accordingly some of the gates were opened by [legionaries], and as soon as a few others had entered, all, both inside and outside, at a given signal, raised a shout and struck their spears upon their shields, and the trumpeters blew a blast, with the result that utter panic overwhelmed the Syracusans.

In 27 BC, the emperor Augustus was awarded a golden shield by the Senate for his part in ending the civil war and 'restoring' the Republic, according to the Res Gestae Divi Augusti. The shield, the Res Gestae says, was hung outside the Curia Julia, serving as a symbol of the Princeps' "valour, clemency, justice and piety".[12] The 5th century writer Vegetius added that scuta helped in identification:

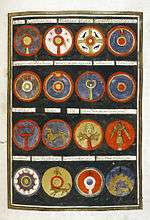

Lest the soldiers in the confusion of battle should be separated from their comrades, every cohort had its shields painted in a manner peculiar to itself. The name of each soldier was also written on his shield, together with the number of the cohort and century to which he belonged.

However, since Vegetius was not a military man and his works (for example De Re Militari) freely, anachronistically mixed the present with the dim and distant past, we must take his descriptions with a grain of salt. Shields in Vegetius' day were used to distinguish between units, but, contrary to his claim here, there is little evidence that this was true of the earlier empire.

Other uses of the word

The name Scutum has been adopted as one of the 88 modern constellations, and by UK luxury clothing maker Aquascutum, which became famous in the 19th century for its waterproof menswear. Hence the name, which in Latin means "water shield'".

In zoology, the term scute or scutum is used for a flat and hardened part of the anatomy of an animal, such as the shell of a turtle.

Notes

- ↑ Sallust, The Conspiracy of Catiline, 51

- ↑ Livy, The History of Rome, 8.8.3

- ↑ Plutarch Parallel Lives, Camillus, 40.4

- ↑ Couissin P., Les armes romaines, pp. 224, 240-7

- ↑ Salmon, E.T., Samnium and the Samnites (1967), p.107

- ↑ "The Histories of Polybius". University of Chicago. p. 319. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ↑ Sabin, Philip; van Wees, Hans; Whitby, Michael (2007). The Cambridge History of Greek and Roman Warfare. 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 196.

- ↑ "The Arms and Armour from Dura-Europos, Syria : Weaponry Recovered from the Roman Garrison Town and the Sassanid Siegeworks during the Excavations, 1922-37". University College London (University of London). Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ↑ "Scutum (Shield)". Yale University Art Gallery. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ↑ "The Histories of Polybius". University of Chicago. p. 499. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ↑ "The Life of Julius Caesar, from The Lives of the Twelve Caesars by C. Suetonius Tranquillus". University of Chicago. p. 91. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ↑ "The Res Gestae of Augustus". University of Chicago. p. 400. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

References

- James, Simon (2004). Excavations at Dura-Europos 1928–1937. Final Report VII. The Arms and Armour and Other Military Equipment. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 0-7141-2248-3.

- McDowall, Simon (1994). Late Roman Infantryman AD236–565. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-8553-2419-0

- Nabbefeld, Ansgar (2008). Roman Shields. Studies on archaeological finds and iconographic evidence from the end of Republic to the late Empire. Cologne. ISBN 978-3-89646-138-4

- Robinson, H.R. (1975). The Armour of Imperial Rome. London: Arms and Armour Press. ISBN 0-85368-219-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shield patterns of Ancient Rome. |

- "Roman Military Equipment", Roman Shields (web museum)

- Lacus Curtius Online, University of Chicago for online translations of Plutarch, Polybius, Cassius Dio and other antique authors

- "Roman Shield Study Material", Roman Legion Shield Patterns (group) for the Study and Photographs of Roman Legion and Auxillia Shield and Painting Patterns