Free climbing

| Part of a series on |

| Climbing |

|---|

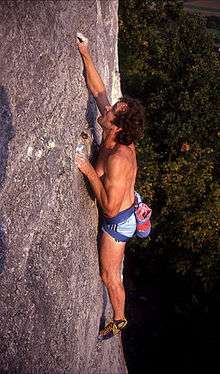

While a rope and other gear may be used for safety when free climbing, they are not used for making upward progress. |

| Background |

| Types |

| Lists |

| Terms |

| Gear |

| Climbing companies |

|

Free climbing is a form of rock climbing in which the climber may use climbing equipment such as ropes and other means of climbing protection, but only to protect against injury during falls and not to assist progress. The climber makes progress by using physical ability to move over the rock via handholds and footholds. [1] Free climbing more specifically may include solo climbing, traditional climbing, sport climbing and bouldering.

The term free climbing is used in constrast to aid climbing, in which specific aid climbing equipment is used to assist the climber in ascending the climb. The term free climbing originally meant "free from direct aid".[2]

Methods and techniques

In lead climbing, a climber climbs a route from the ground up. For protection against a fall, the lead climber trails a rope which is managed by a belayer who remains on the ground or at an established anchor. As the leader climbs, they either place traditional protection such as cams and stoppers, or clip their rope through pre-placed bolted hangers or fixed anchors. The belayer feeds rope to the lead climber through a belay device, keeping a minimum amount of slack in the system, and keeping themself ready to catch the leader in case of a fall. The leader climbs until the top is reached, and they can then belay the following climber from above.

Both climber and belayer attach the rope to their climbing harnesses. The rope is tied into the climber's harness with a figure-of-eight loop or double bowline knot. The leader either places their own protection or clips into permanent protection already attached to the rock. In traditional climbing, the protection generally is removable. However, many significant first ascents in the U.S. done with a combination of crack gear and bolts placed on lead were termed "traditional" at the time (see below discussion). Usually nuts or spring-loaded camming devices (often referred to as "cams" or "friends") are set in cracks in the rock (although pitons are sometimes used). In sport climbing the protection is metal loops called hangers. Hangers are secured to the rock with either expanding masonry bolts taken from the construction industry, or by placing glue-in bolt systems. In ice climbing the protection is made-up of ice screws or similar devices hammered or screwed into the ice by the leader, and removed by the second climber.

The lead climber typically connects the rope to the protection with carabiners or quickdraws. If the lead climber falls, they will fall twice the length of the rope from the last protection point, plus rope stretch (typically 5% to 8% of the rope out), plus slack. If any of the gear breaks or pulls out of the rock or if the belayer fails to lock off the belay device immediately, the fall will be significantly longer. Thus if a climber is 2 meters above the last protection they will fall 2 meters to the protection, 2 meters below the protection, plus rope stretch (typ., 0.10–0.16 m) and slack, for a total fall of over 4 meters.

If the leader falls, the belayer must arrest the rope to stop the fall. To achieve this the rope is run through a belay device attached to the belayer's harness. The belay device runs the rope through a series of sharp curves that, when operated properly, greatly increases friction and stops the rope from running. Some of the more popular types of belay devices are the ATC Belay Device, the Figure 8 and various assisted-braking belay devices such as the Petzl Gri-Gri.

If the route being climbed is a multi-pitch route the leader sets up a secure anchor system at the top of the pitch, also called a belay, from where they can belay as their partner climbs. As the second climber climbs, they remove the gear from the rock in case of traditional climbing or remove the quickdraws from the bolts in the case of sport climbing. Both climbers are now at the top of the pitch with all their equipment. Note that the second climber is protected from above while climbing, but the lead climber is not, so being the lead climber is more challenging and dangerous. After completing the climb, and with both climbers at the top of the pitch, both climbers must rappel or descend the climb in order to return to their starting point, or top out and walk off. All climbs do not necessarily require the lead climber to belay the second climber from the top. The belayer could lower the lead climber down after they have completed a single pitch route.

Style

There are no rules per se to free climbing, beyond showing respect for the rock and for other climbers.

Over the years, as climbing has become more popular and climbers more skilled, an entire generation of aficionados has been spawned from and with the ethics of climbing gyms and sport climbing. These climbers now share the rocks in some places with traditionally-trained adherents.

In the newer generation as in previous ones, certain new conventions have emerged as the state of the art changes. Conventions are not universal: in fact, many older and/or more traditionally oriented climbers may ignore or actively disdain certain newer conventions, and the reverse is true as well: The more traditional values may be regarded as irrelevant, antique or "un-fun" by those who have different experience, goals and cultural identity.

While sport climbers are more likely than traditional climbers to frequently attempt routes that are too hard to successfully ascend on the first try, and repeat until successful, both cultures value positively:

- Climbing a given route on the first try without any advance firsthand knowledge of it (so-called on-sighting).

- Making a flawless ascent, perhaps repeating a route which has previously been climbed in "poor style"

- Advancing the state of the art, perhaps by developing a new route, or by climbing an established route in a creative, novel way

As matters of style, any of the following are likely to be regarded similarly by most free climbers across the various cultures. Generally, the following diminish the perception of "good style":

- Pre-climb inspections (to learn the nuances of a route rather than assessing the route from a safety point of view)

- Resting on gear or rope (hangdogging)

- Pre-placing gear (pinkpointing)

- Pulling or weighting gear aid-style (french free)

- Prior top roping (headpointing) before sending on lead

- Practice through falling (generally more relevant in sport climbing than traditional)

Common misunderstandings of the term

While clear in its contrast to aid climbing, the term free climbing is nonetheless prone to misunderstanding and misuse.

The two most common errors are:

- Confusing free climbing with its subset free soloing, a willfully risk-taking endeavor involving climbing with just one's hands, feet, and body without any rope or protective equipment.

- Confusing soloing a free climb with free soloing, "soloing" alone meaning merely to climb with no partner, which depending on the difficulty of the route can be done safely using any of a number of self-belaying systems. In the UK the term "soloing" refers to soloing free (no aid sections) routes.

.jpg)

Notable first ascents

In free climbing, a first ascent (FA), or first free ascent (FFA) is the first successful, documented climb of a route or boulder performed without using equipment such as anchors, quickdraws or ropes for aiding progression or resting.

Ratings on the hardest climbs tend to be speculative, until other climbers have had a chance to complete the routes and a consensus can be reached on the precise grade. This becomes increasingly difficult as the grade increases as there are fewer climbers that are capable of repeating the ascent of a route and passing judgment on its grade.

As of October 2017:

- The hardest ascended route (Silence) has a proposed grade of 9c (5.15d). It was first ascended by Adam Ondra in 2017[3] and no one else has been able to repeat it.

- The hardest route ever ascended by a woman is La Planta de Shiva, graded 9b (5.15b). Angela Eiter claimed its first female ascent in 2017[4][5] and no other woman has been able to repeat it.

- The hardest ascended boulder problem (Burden of dreams) has a proposed grade of 9A (V17). It was first ascended by Nalle Hukkataival in 2016[6] and no one else has been able to repeat it.

- The hardest routes ever successfully climbed on-sight are graded 9a (5.14d). The first on-sight ascent of a 9a (5.14d) route (Estado Critico) was claimed by Alex Megos in March 2013.[7] The second (Cabane au Canada) by Adam Ondra in July 2013.[8] No one else has been able to onsight this grade.

References

- ↑ Mountaineering The freedom of the hills (7 ed.). Seattle, Washington, USA: The Mountaineers Books. 2009. p. 209. ISBN 0-89886-828-9.

- ↑ Bachar, John; Boga, Steven (1996). Free Climbing With John Bachar. Stackpole Books. p. 1. ISBN 9780811725170.

- ↑ planetmountain.com, ed. (September 4, 2017). "Interview: Adam Ondra climbs world's first 9c at Flatanger in Norway". Retrieved September 4, 2017.

- ↑ Planet Mountain (ed.). "Interview with Angela Eiter, the first woman to climb 9b". Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- ↑ Planet Mountain (ed.). "Angela Eiter climbs historic first female 9b". Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- ↑ Planet Mountain (ed.). "Nalle Hukkataival climbs Burden of Dreams and proposes world's first 9a boulder problem".

- ↑ "First 9A onsight by Alex Mesgos".

- ↑ Björn Pohl (9 July 2013). "La cabane au Canada, 9a, onsight by Ondra". ukclimbing.com. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

Bibliography

- The French Spiderman (La légende de l'homme araignée), DVD, director Olivier Van'L.

- La légende de l'homme araignée on IMDb .

Further reading

- How to Rock Climb, John Long