Focal point (game theory)

In game theory, a focal point (also called Schelling point) is a solution that people will tend to use in the absence of communication, because it seems natural, special, or relevant to them. The concept was introduced by the Nobel Memorial Prize-winning American economist Thomas Schelling in his book The Strategy of Conflict (1960).[1] In this book (at p. 57), Schelling describes "focal point[s] for each person's expectation of what the other expects him to expect to be expected to do". This type of focal point later was named after Schelling. He further explains that such points are highly useful in negotiations, because we cannot completely trust our negotiating partners' words.

Examples

In coordination games

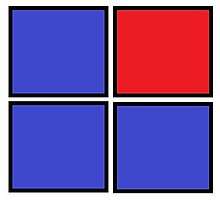

In a simple example: two people unable to communicate with each other are each shown a panel of four squares and asked to select one; if and only if they both select the same one, they will each receive a prize. Three of the squares are blue and one is red. Assuming they each know nothing about the other player, but that they each do want to win the prize, then they will, reasonably, both choose the red square.

The red square is not in a sense a better square; they could win by both choosing any square and in this sense, all squares are technically a Nash equilibrium. The red square is the "right" square to select only if a player can be sure that the other player has selected it; but by hypothesis neither can. However, it is the most salient and notable square, so—lacking any other one—most people will choose it, and this will in fact (often) work.

Schelling's example

Schelling illustrated this concept with the following problem: "Tomorrow you have to meet a stranger in NYC. Where and when do you meet them?" This is a coordination game, where any place and time in the city could be an equilibrium solution. Schelling asked a group of students this question, and found the most common answer was "noon at (the information booth at) Grand Central Terminal". There is nothing that makes Grand Central Terminal a location with a higher payoff (you could just as easily meet someone at a bar or the public library reading room), but its tradition as a meeting place raises its salience and therefore makes it a natural "focal point".[1]

Real-life application

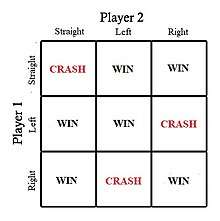

Focal points can also have real-life applications. For example, imagine two bicycles headed towards each other and in danger of crashing. Avoiding collision becomes a coordination game where each player's winning choice depends on the other player's choice. Each player in this case has the choice to go straight, swerve to the left or swerve to the right. Both players want to avoid crashing, but neither knows what the other will do.[2]

In this case, the decision to swerve right can serve as a focal point which leads to the winning right-right outcome. It seems a natural focal point in places using right-hand traffic.

Criticism

After Schelling wrote about it, a number of experimental investigations have been performed on the efficacy of focal point in coordination situations and research has generally validated it. A review by Isoni et al. looked at studies that used the Battle of the Sexes game that showed players' preferences to more salient options; these included Holm's 2000 study which found that when this game is played between a male and a female player, the subjects are more likely to coordinate on an equilibrium whose payoffs were more favorable to the male.[3][4][5][6]

However, some studies have also demonstrated that the power of focal point can be greatly weakened by asymmetric payoff. In Crawford et al.'s 2008 study, subjects played coordination games in symmetric payoff and asymmetric payoff conditions. While 90% of subjects in the symmetry condition (in which the subjects would win $100 if they were able to coordinate regardless of what they coordinated on) were able to coordinate on the focal point, only 60% chose the more salient option in the slight asymmetry condition (in which the subjects would win $100 by coordinating on the salient option and $101 for the non-salient option). This effect would become more profound as the asymmetry in payoffs become more exaggerated.[7][8][9]

See also

References

- 1 2 Schelling, Thomas C. (1960). The strategy of conflict (First ed.). Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-84031-3.

- ↑ "Focal Points (or Schelling Points): How We Naturally Organize in Games of Coordination – Mind Your Decisions". mindyourdecisions.com. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- ↑ "Testing the Focal Point Theory of Legal Compliance: The Effect of Third-Party Expression in an Experimental Hawk/Dove Game" (PDF). 2005.

- ↑ Mehta, Judith; Starmer, Chris; Sugden, Robert (1994-03-01). "Focal points in pure coordination games: An experimental investigation". Theory and Decision. 36 (2): 163–185. doi:10.1007/BF01079211. ISSN 0040-5833.

- ↑ "Focal points in tacit bargaining problems: Experimental evidence". European Economic Review. 59: 167–188. 2013-04-01. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2012.12.005. ISSN 0014-2921.

- ↑ "Gender-Based Focal Points". Games and Economic Behavior. 32 (2): 292–314. 2000-08-01. doi:10.1006/game.1998.0685. ISSN 0899-8256.

- ↑ "Focal points in tacit bargaining problems: Experimental evidence". European Economic Review. 59: 167–188. 2013-04-01. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2012.12.005. ISSN 0014-2921.

- ↑ "Stake size and the power of focal points in coordination games: Experimental evidence". Games and Economic Behavior. 94: 191–199. 2015-11-01. doi:10.1016/j.geb.2015.05.001. ISSN 0899-8256.

- ↑ "The Power of Focal Points Is Limited: Even Minute Payoff Asymmetry May Yield Large Coordination Failures" (PDF). 2008.

External links

- Rare Entries Contests (an example) and Common Entries Contests, games of respectively avoiding and seeking out focal points

- TED community experiment on focal / Schelling points