Subgame perfect equilibrium

| Subgame Perfect Equilibrium | |

|---|---|

| A solution concept in game theory | |

| Relationship | |

| Subset of | Nash equilibrium |

| Intersects with | Evolutionarily stable strategy |

| Significance | |

| Proposed by | Reinhard Selten |

| Used for | Extensive form games |

| Example | Ultimatum game |

In game theory, a subgame perfect equilibrium (or subgame perfect Nash equilibrium) is a refinement of a Nash equilibrium used in dynamic games. A strategy profile is a subgame perfect equilibrium if it represents a Nash equilibrium of every subgame of the original game. Informally, this means that if the players played any smaller game that consisted of only one part of the larger game, their behavior would represent a Nash equilibrium of that smaller game. Every finite extensive game has a subgame perfect equilibrium.[1]

A common method for determining subgame perfect equilibria in the case of a finite game is backward induction. Here one first considers the last actions of the game and determines which actions the final mover should take in each possible circumstance to maximize his/her utility. One then supposes that the last actor will do these actions, and considers the second to last actions, again choosing those that maximize that actor's utility. This process continues until one reaches the first move of the game. The strategies which remain are the set of all subgame perfect equilibria for finite-horizon extensive games of perfect information.[1] However, backward induction cannot be applied to games of imperfect or incomplete information because this entails cutting through non-singleton information sets.

A subgame perfect equilibrium necessarily satisfies the One-Shot deviation principle.

The set of subgame perfect equilibria for a given game is always a subset of the set of Nash equilibria for that game. In some cases the sets can be identical.

The Ultimatum game provides an intuitive example of a game with fewer subgame perfect equilibria than Nash equilibria.

Example

Determining the subgame perfect equilibrium by using backward induction is shown below in Figure 1. Strategies for Player 1 are given by {Up, Uq, Dp, Dq}, whereas Player 2 has the strategies among {TL, TR, BL, BR}. There are 4 subgames in this example, with 3 proper subgames.

Using the backward induction, the players will take the following actions for each subgame:

- Subgame for actions p and q: Player 1 will take action p with payoff (3, 3) to maximize Player 1’s payoff, so the payoff for action L becomes (3,3).

- Subgame for actions L and R: Player 2 will take action L for 3 > 2, so the payoff for action D becomes (3, 3).

- Subgame for actions T and B: Player 2 will take action T to maximize Player 2’s payoff, so the payoff for action U becomes (1, 4).

- Subgame for actions U and D: Player 1 will take action D to maximize Player 1’s payoff.

Thus, the subgame perfect equilibrium is {Dp, TL} with the payoff (3, 3).

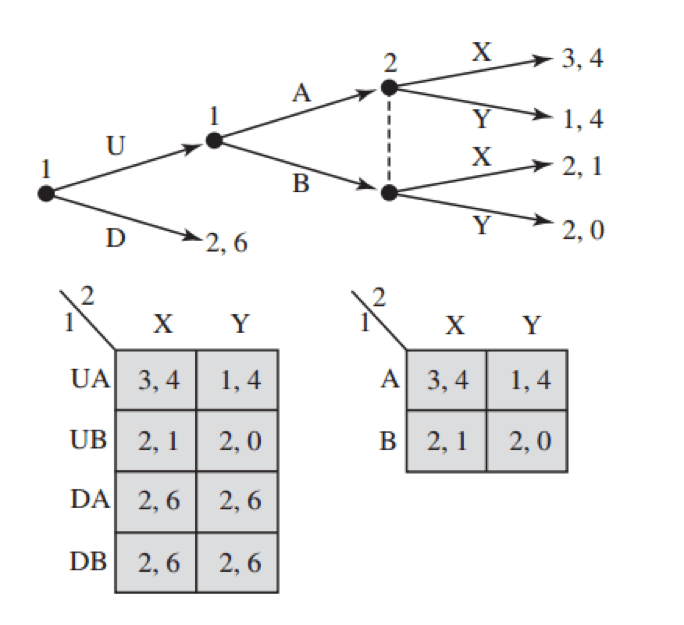

An extensive-form game with incomplete information is presented below in Figure 2. Note that the node for Player 1 with actions A and B, and all succeeding actions is a subgame. Player 2’s nodes are not a subgame as they are part of the same information set.

The first normal-form game is the normal form representation of the whole extensive-form game. Based on the provided information, (UA, X), (DA, Y), and (DB, Y) are all Nash equilibria for the entire game.

The second normal-form game is the normal form representation of the subgame starting from Player 1’s second node with actions A and B. For the second normal-form game, the Nash equilibrium of the subgame is (A, X).

For the entire game Nash equilibria (DA, Y) and (DB, Y) are not subgame perfect equlibria because the move of Player 2 does not constitute a Nash Equilibrium. The Nash equilibrium (UA, X) is subgame perfect because it incorporates the subgame Nash equilibrium (A, X) as part of its strategy.[2]

Subgame-perfect equilibrium in finitely repeated games

For finitely repeated games, if a stage game has only one unique Nash equilibrium, the subgame perfect equilibrium is to play without considering past actions, treating the current subgame as a one-shot game. An example of this is a finitely repeated Prisoner’s dilemma game. Using backward induction, the last subgame in a finitely repeated Prisoner’s dilemma requires players to play the unique Nash equilibrium (both players defecting). Because of this, all games prior to the last subgame will also play the Nash equilibrium to maximize their single-period payoffs.

If a stage-game in a finitely repeated game has multiple Nash equilibria, subgame perfect equilibria can be constructed to play non-stage-game Nash equilibrium actions, through a “carrot and stick” structure. One player can use the one stage-game Nash equilibrium to incentivize playing the non-Nash equilibrium action, while using a stage-game Nash equilibrium with lower payoff to the other player if they choose to defect.[3]

Finding subgame-perfect equilibria

Reinhard Selten proved that any game which can be broken into "sub-games" containing a sub-set of all the available choices in the main game will have a subgame perfect Nash Equilibrium strategy (possibly as a mixed strategy giving non-deterministic sub-game decisions). Subgame perfection is only used with games of complete information. Subgame perfection can be used with extensive form games of complete but imperfect information.

The subgame-perfect Nash equilibrium is normally deduced by "backward induction" from the various ultimate outcomes of the game, eliminating branches which would involve any player making a move that is not credible (because it is not optimal) from that node. One game in which the backward induction solution is well known is tic-tac-toe, but in theory even Go has such an optimum strategy for all players.

The interesting aspect of the word "credible" in the preceding paragraph is that taken as a whole (disregarding the irreversibility of reaching sub-games) strategies exist which are superior to subgame perfect strategies, but which are not credible in the sense that a threat to carry them out will harm the player making the threat and prevent that combination of strategies. For instance in the game of "chicken" if one player has the option of ripping the steering wheel from their car they should always take it because it leads to a "sub game" in which their rational opponent is precluded from doing the same thing (and killing them both). The wheel-ripper will always win the game (making his opponent swerve away), and the opponent's threat to suicidally follow suit is not credible.

See also

References

- 1 2 Osborne, M. J. (2004). An Introduction to Game Theory. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Joel., Watson,. Strategy : an introduction to game theory (Third ed.). New York. ISBN 9780393918380. OCLC 842323069.

- ↑ Takako,, Fujiwara-Greve,. Non-cooperative game theory. Tokyo. ISBN 9784431556442. OCLC 911616270.