First Folio

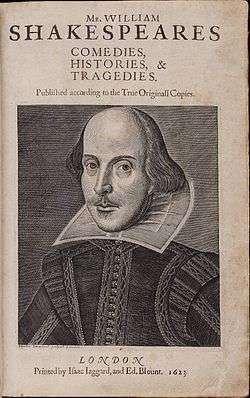

Title page of the first impression (1623). | |

| Author | William Shakespeare |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Martin Droeshout |

| Country | England |

| Language | Early Modern English |

| Genre | English Renaissance theatre |

| Publisher | Edward Blount and William and Isaac Jaggard |

Publication date | 1623 |

| Pages | c. 900 |

Mr. William Shakespeare's Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies is the 1623 published collection of William Shakespeare's plays. Modern scholars commonly refer to it as the First Folio.[lower-alpha 1] The First Folio is considered one of the most influential books ever published in the English language.[1]

Printed in folio format and containing 36 plays (see list of Shakespeare's plays), it was prepared by Shakespeare's colleagues John Heminges and Henry Condell. It was dedicated to the "incomparable pair of brethren" William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke and his brother Philip Herbert, Earl of Montgomery (later 4th Earl of Pembroke).

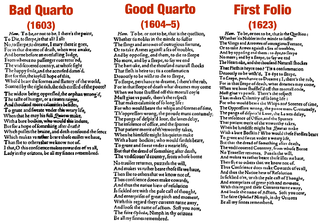

Although 18 of Shakespeare's plays had been published in quarto before 1623, the First Folio is arguably the only reliable text for about 20 of the plays, and a valuable source text for many of those previously published. The Folio includes all of the plays generally accepted to be Shakespeare's, with the exception of Pericles, Prince of Tyre; The Two Noble Kinsmen; and the two lost plays, Cardenio and Love's Labour's Won.

Background

On 23 April 1616,[lower-alpha 2] William Shakespeare died in Stratford-upon-Avon, and was buried in the chancel of the Church of the Holy Trinity two days later. After a long career as an actor, dramatist, and sharer in the Lord Chamberlain's Men (later the King's Men) from c. 1585–90[lower-alpha 3] until c. 1610–13,[lower-alpha 4] he was financially well off and among England's most popular dramatists, both on the stage and in print.[11][lower-alpha 5] But his reputation had not yet risen to the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist.[12][13][14] A funerary monument in Holy Trinity was commissioned, probably by his oldest daughter, and installed, most likely sometime before 1617–18, but a monument in Poets' Corner in Westminster Abbey[lower-alpha 6] was not realised until 1740. William Basse wrote an elegiac poem on him c. 1618–20, but no notices were taken of his death in diplomatic correspondence or newsletters on the continent, nor were any tributes published by European contemporaries. William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke—who at the time held the post of Lord Chamberlain, with authority over the King's Men, and directly in charge of Shakespeare as a Groom of the Chamber—made no note of his passing.[15][lower-alpha 7]

Shakespeare's works—both poetic and dramatic—had a rich history in print before the publication of the First Folio: from the first publications of Venus and Adonis (1593) and The Rape of Lucrece (1594), 78 individual printed editions of his works are known. c. 30% (23) of these editions are his poetry, and the remaining c. 70% (55) his plays. Counting by number of editions published before 1623, the best-selling works were Venus and Adonis (12 editions), The Rape of Lucrece (6 editions), and Henry IV, Part 1 (6 editions). Of the 23 editions of the poems, 16 were published in octavo; the rest, and almost all of the editions of the plays, were printed in quarto.[16] The quarto format was made by folding a large sheet of printing paper twice, forming 4 leaves with 8 pages. The average quarto measured 7 by 9 inches (18 by 23 cm) and was made up of c. 9 sheets, giving 72 total pages.[17] Octavos—made by folding a sheet of the same size three times, forming 8 leaves with 16 pages—were about half as large as a quarto.[16] Since the cost of paper represented c. 50–75% of a book's total production costs,[17] octavos were generally cheaper to manufacture than quartos, and a common way to reduce publishing costs was to reduce the number of pages needed by compressing (using two columns or a smaller typeface) or abbreviating the text.[16]

| “ | [Publish me in] the Smallest size, |

” |

| — Henry Fitzgeffrey, Certain Elegies (1618) | ||

Editions of individual plays were typically published in quarto and could be bought for 6d (equivalent to £4 in 2016) without a binding. These editions were primarily intended to be cheap and convenient, and read until worn out or repurposed as wrapping paper (or worse), rather than high quality objects kept in a library.[17] Customers who wanted to keep a particular play would have to have it bound, and would typically bind several related or miscellany plays into one volume.[18] Octavos, though nominally cheaper to produce, were somewhat different. From c. 1595–6 (Venus and Adonis) and 1598 (The Rape of Lucrece), Shakespeare's narrative poems were published in octavo.[19] In The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare's First Folio, Tara L. Lyons argues that this was partly due to the publisher, John Harrison's, desire to capitalize on the poems' association with Ovid: the Greek classics were sold in octavo, so printing Shakespeare's poetry in the same format would strengthen the association.[20] The octavo generally carried greater prestige, so the format itself would help to elevate their standing.[19] Ultimately, however, the choice was a financial one: Venus and Adonis in octavo needed four sheets of paper, versus seven in quarto, and the octavo The Rape of Lucrece needed five sheets, versus 12 in quarto.[20] Whatever the motivation, the move seems to have had the intended effect: Francis Meres, the first known literary critic to comment on Shakespeare, in his Palladis Tamia (1598), puts it thus: "the sweete wittie soule of Ouid liues in mellifluous & hony-tongued Shakespeare, witnes his Venus and Adonis, his Lucrece, his sugred Sonnets among his priuate friends".[21]

| “ | Pray tell me Ben, where does the mystery lurk, |

” |

| — anonymous, Wits Recreations' (1640) | ||

Publishing literary works in folio was not unprecedented. Starting with the publication of Sir Philip Sidney's The Countess of Pembroke's Arcadia (1593) and Astrophel and Stella (1598), both published by William Ponsonby, there was a significant number of folios published, and a significant number of them were published by the men who would later be involved in publishing the First Folio.[lower-alpha 8] But quarto was the typical format for plays printed in the period: folio was a prestige format, typically used, according to Fredson Bowers, for books of "superior merit or some permanent value".[23]

Printing

The contents of the First Folio were compiled by John Heminges and Henry Condell;[24] the members of the Stationers Company who published the book were the booksellers Edward Blount and the father/son team of William and Isaac Jaggard. William Jaggard has seemed an odd choice by the King's Men because he had published the questionable collection The Passionate Pilgrim as Shakespeare's, and in 1619 had printed new editions of 10 Shakespearean quartos to which he did not have clear rights, some with false dates and title pages (the False Folio affair). Indeed, his contemporary Thomas Heywood, whose poetry Jaggard had pirated and misattributed to Shakespeare, specifically reports that Shakespeare was "much offended with M. Jaggard (that altogether unknown to him) presumed to make so bold with his name."[25]

Heminges and Condell emphasised that the Folio was replacing the earlier publications, which they characterised as "stol'n and surreptitious copies, maimed and deformed by frauds and stealths of injurious impostors", asserting that Shakespeare's true words "are now offer'd to your view cured, and perfect of their limbes; and all the rest, absolute in their numbers as he conceived them."

The paper industry in England was then in its infancy and the quantity of quality rag paper for the book was imported from France.[26] It is thought that the typesetting and printing of the First Folio was such a large job that the King's Men simply needed the capacities of the Jaggards' shop. William Jaggard was old, infirm and blind by 1623, and died a month before the book went on sale; most of the work in the project must have been done by his son Isaac.

The First Folio's publishing syndicate also included two stationers who owned the rights to some of the individual plays that had been previously printed: William Aspley (Much Ado About Nothing and Henry IV, Part 2) and John Smethwick (Love's Labour's Lost, Romeo and Juliet, and Hamlet). Smethwick had been a business partner of another Jaggard, William's brother John.

The printing of the Folio was probably done between February 1622 and early November 1623. It is possible that the printer originally expected to have the book ready early, since it was listed in the Frankfurt Book Fair catalogue as a book to appear between April and October 1622, but the catalog contained many books not yet printed by 1622, and the modern consensus is that the entry was simply intended as advance publicity.[27] The first impression had a publication date of 1623, and the earliest record of a retail purchase is an account book entry for 5 December 1623 of Edward Dering (who purchased two); the Bodleian Library, in Oxford, received its copy in early 1624 (which it subsequently sold for £24 as a superseded edition when the Third Folio became available in 1663/1664).[28]

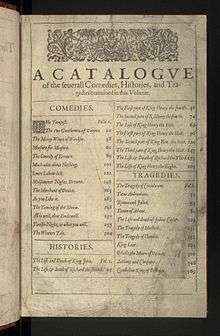

Contents

The 36 plays of the First Folio occur in the order given below; plays that had never been published before 1623 are marked with an asterisk. Each play is followed by the type of source used, as determined by bibliographical research.[29]

The term foul papers refers to Shakespeare's working drafts of a play. When completed, a transcript or fair copy of the foul papers would be prepared, by the author or by a scribe. Such a manuscript would have to be heavily annotated with accurate and detailed stage directions and all the other data needed for performance, and then could serve as a prompt book, to be used by the prompter to guide a performance of the play. Any of these manuscripts, in any combination, could be used as a source for a printed text. On rare occasions a printed text might be annotated for use as a prompt book, as may have been the case with A Midsummer Night's Dream. The label Qn denotes the nth quarto edition of a play.

- Comedies

- 1 The Tempest * – the play was set into type from a manuscript prepared by Ralph Crane, a professional scrivener employed by the King's Men. Crane produced a high-quality result, with formal act/scene divisions, frequent use of parentheses and hyphenated forms, and other identifiable features.

- 2 The Two Gentlemen of Verona * – another transcript by Ralph Crane.

- 3 The Merry Wives of Windsor – another transcript by Ralph Crane.

- 4 Measure for Measure * – probably another Ralph Crane transcript.

- 5 The Comedy of Errors * – probably typeset from Shakespeare's "foul papers," lightly annotated.

- 6 Much Ado About Nothing – typeset from a copy of the quarto, lightly annotated.

- 7 Love's Labour's Lost – typeset from a corrected copy of Q1.

- 8 A Midsummer Night's Dream – typeset from a copy of Q2, well-annotated, possibly used as a prompt-book.

- 9 The Merchant of Venice – typeset from a lightly edited and corrected copy of Q1.

- 10 As You Like It * – from a quality manuscript, lightly annotated by a prompter.

- 11 The Taming of the Shrew * – typeset from Shakespeare's "foul papers," somewhat annotated, perhaps as preparation for use as a prompt-book.

- 12 All's Well That Ends Well * – probably from Shakespeare's "foul papers" or a manuscript of them.

- 13 Twelfth Night * – typeset either from a prompt-book or a transcript of one.

- 14 The Winter's Tale * – another transcript by Ralph Crane.

- Histories

- 15 King John * – uncertain: a prompt-book, or "foul papers."

- 16 Richard II – typeset from Q3 and Q5, corrected against a prompt-book.

- 17 Henry IV, Part 1 – typeset from an edited copy of Q5.

- 18 Henry IV, Part 2 – uncertain: some combination of manuscript and quarto text.

- 19 Henry V – typeset from Shakespeare's "foul papers."

- 20 Henry VI, Part 1 * – likely from an annotated transcript of the author's manuscript.

- 21 Henry VI, Part 2 – probably a Shakespearean manuscript used as a prompt-book.

- 22 Henry VI, Part 3 – like 2H6, probably a Shakespearean prompt-book.

- 23 Richard III – a difficult case: probably typeset partially from Q3, and partially from Q6 corrected against a manuscript (maybe "foul papers").

- 24 Henry VIII * – typeset from a fair copy of the authors' manuscript.

- Tragedies

- 25 Troilus and Cressida – probably typeset from the quarto, corrected with Shakespeare's "foul papers," printed after the rest of the Folio was completed.

- 26 Coriolanus * – set from a high-quality authorial transcript.

- 27 Titus Andronicus – typeset from a copy of Q3 that might have served as a prompt-book.

- 28 Romeo and Juliet – in essence a reprint of Q3.

- 29 Timon of Athens * – set from Shakespeare's foul papers or a transcript of them.

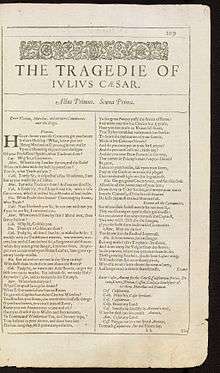

- 30 Julius Caesar * – set from a prompt-book, or a transcript of a prompt-book.

- 31 Macbeth * – probably set from a prompt-book, perhaps detailing an adaptation of the play for a short indoor performance

- 32 Hamlet – one of the most difficult problems in the First Folio: probably typeset from some combination of Q2 and manuscript sources.

- 33 King Lear – a difficult problem: probably set mainly from Q1 but with reference to Q2, and corrected against a prompt-book.

- 34 Othello – another difficult problem: probably typeset from Q1, corrected with a quality manuscript.

- 35 Antony and Cleopatra * – possibly "foul papers" or a transcript of them.

- 36 Cymbeline * – possibly another Ralph Crane transcript, or else the official prompt-book.

Troilus and Cressida was originally intended to follow Romeo and Juliet, but the typesetting was stopped, probably due to a conflict over the rights to the play; it was later inserted as the first of the tragedies, when the rights question was resolved. It does not appear in the table of contents.[30]

Introductory Poem

Ben Jonson wrote a preface to the folio with this poem facing the Droeshout portrait:

This Figure, that thou here seest put,

It was for gentle Shakespeare cut:

Wherein the Grauer had a strife

with Nature, to out-doo the life:

O, could he but haue dravvne his vvit

As vvell in brasse, as he hath hit

His face; the Print vvould then surpasse

All, that vvas euer vvrit in brasse.

But, since he cannot, Reader, looke

Not on his picture, but his Booke.

B.J.

Compositors

As far as modern scholarship has been able to determine,[31] the First Folio texts were set into type by five compositors, with different spelling habits, peculiarities, and levels of competence. Researchers have labelled them A through E, A being the most accurate, and E an apprentice who had significant difficulties in dealing with manuscript copy. Their shares in typesetting the pages of the Folio break down like this:

| Comedies | Histories | Tragedies | Total pages | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| "A" | 74 | 80 | 40 | 194 |

| "B" | 143 | 89 | 213 | 445 |

| "C" | 79 | 22 | 19 | 120 |

| "D" | 35 1⁄2 | 0 | 0 | 35 1⁄2 |

| "E" | 0 | 0 | 71 1⁄2 | 71 1⁄2 |

Compositor "E" was most likely one John Leason, whose apprenticeship contract dated only from 4 November 1622. One of the other four might have been a John Shakespeare, of Warwickshire, who apprenticed with Jaggard in 1610–17. ("Shakespeare" was a common name in Warwickshire in that era; John was no known relation to the playwright.)

The First Folio and variants

W. W. Greg has argued that Edward Knight, the "book-keeper" or "book-holder" (prompter) of the King's Men, did the actual proofreading of the manuscript sources for the First Folio. Knight is known to have been responsible for maintaining and annotating the company's scripts, and making sure that the company complied with cuts and changes ordered by the Master of the Revels.

Some pages of the First Folio – 134 out of the total of 900 – were proofread and corrected while the job of printing the book was ongoing. As a result, the Folio differs from modern books in that individual copies vary considerably in their typographical errors. There were about 500 corrections made to the Folio in this way.[32] These corrections by the typesetters, however, consisted only of simple typos, clear mistakes in their own work; the evidence suggests that they almost never referred back to their manuscript sources, let alone tried to resolve any problems in those sources. The well-known cruxes in the First Folio texts were beyond the typesetters' capacity to correct.

The Folio was typeset and bound in "sixes" – 3 sheets of paper, taken together, were folded into a booklet-like quire or gathering of 6 leaves, 12 pages. Once printed, the "sixes" were assembled and bound together to make the book. The sheets were printed in 2-page formes, meaning that pages 1 and 12 of the first quire were printed simultaneously on one side of one sheet of paper (which became the "outer" side); then pages 2 and 11 were printed on the other side of the same sheet (the "inner" side). The same was done with pages 3 and 10, and 4 and 9, on the second sheet, and pages 5 and 8, and 6 and 7, on the third. Then the first quire could be assembled with its pages in the correct order. The next quire was printed by the same method: pages 13 and 24 on one side of one sheet, etc. This meant that the text being printed had to be "cast off" – the compositors had to plan beforehand how much text would fit onto each page. If the compositors were setting type from manuscripts (perhaps messy, revised and corrected manuscripts), their calculations would frequently be off by greater or lesser amounts, resulting in the need to expand or compress. A line of verse could be printed as two; or verse could be printed as prose to save space, or lines and passages could even be omitted (a disturbing prospect for those who prize Shakespeare's works).[33]

Performing Shakespeare using the First Folio

Some Shakespeare directors and theatre companies producing Shakespeare believe that while modern editions of Shakespeare's plays, which are heavily edited and changed, are more readable, they remove possible actor cues found in the Folio, such as capitalization, different punctuation and even the changing or removal of whole words. Among the theatre companies that have based their production approach upon use of the First Folio was the Riverside Shakespeare Company, which, in the early 1980s, began a studied approach to their stage productions relying upon the First Folio as their textual guide. In the 1990s, the First Folio was reissued in a paperback format more accessible to the general public.[34]

Today, many theatre companies and festivals producing the works of Shakespeare use the First Folio as the basis for their theatrical productions and training programmes, including London's Original Shakespeare Company, a theatre company which works exclusively from cue scripts drawn from the First Folio.[35]

However, what are now the widely accepted versions of these plays include lines taken from the Quartos, which are not in the First Folio. For instance, small passages of Hamlet are omitted – among them Horatio's line "A mote it is to trouble the mind's eye", and his subsequent speech beginning with "In the most high and palmy state of Rome, / A little ere the mightiest Julius fell..." Also missing is Hamlet's encounter with the Norwegian captain from Fortinbras's army in Act IV, Scene IV, along with perhaps the most important cut, the soliloquy "How all occasions do inform against me". Romeo and Juliet omits the prologue, with its famous line about "a pair of star-crossed lovers".

Holdings, sales and valuations

Jean-Christophe Mayer, in The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare's First Folio (2016), estimates the original retail price of the First Folio to be about 15s (equivalent to £127 in 2016) for an unbound copy, and up to £1 (equivalent to £169 in 2016) for one bound in calfskin.[lower-alpha 9] In terms of purchasing power, "a bound folio would be about forty times the price of a single play and represented almost two months’ wages for an ordinary skilled worker."[36]

It is believed that around 750 copies of the First Folio were printed, of which there are 235 known surviving copies.[37][38][39] The British Library holds 5 copies. The National Library of Scotland holds a single copy, donated by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland in 1949.[40] An incomplete copy is on display at the Craven Museum & Gallery in Skipton, North Yorkshire and is accompanied by an audio narrative by Patrick Stewart.[41] The Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C. holds the world's largest collection with 82 copies. Another collection (12 copies) is held at Meisei University in Tokyo, including the Meisei Copy (coded MR 774), said to be unique because of annotations by its reader.[42] While most copies are held in university libraries or museums such as the copy held by the Brandeis University library since 1961,[43] a few are held by public libraries. In the United States, the New York Public Library has six copies[44] with the Boston Public Library,[45] Free Library of Philadelphia,[46] The Rare Book & Manuscript Library (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign),[47] the Lilly Library (Indiana University-Bloomington),[48] and the Dallas Public Library[49] each holding one copy. The Huntington Library in Los Angeles County has four copies.[50] In Canada, there is only one known copy, located in the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library of the University of Toronto.[51] The former Rosenbach copy, in its original binding, is now held at the Fondation Martin Bodmer in Switzerland.[52] The State Library of New South Wales holds copies of the First, Second, Third and Fourth Folios.[53]

The First Folio is one of the most valuable printed books in the world: a copy sold at Christie's in New York in October 2001 made $6.16 million hammer price (then £3.73m).[54]

Oriel College, Oxford, raised a conjectured £3.5 million from the sale of its First Folio to Sir Paul Getty in 2003.

To commemorate the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare's death in 2016, the Folger Shakespeare Library toured some of its 82 First Folios for display in all 50 U.S. states, Washington, D.C. and Puerto Rico.[55]

Discoveries of previously unknown Folios

On 13 July 2006, a complete copy of the First Folio owned by Dr Williams's Library was auctioned at Sotheby's auction house. The book, which was in its original 17th-century binding, sold for £2,808,000, less than Sotheby's top estimate of £3.5 million. This copy is one of only about 40 remaining complete copies (most of the existing copies are incomplete); only one other copy of the book remains in private ownership.[56]

On 11 July 2008, it was reported that a copy stolen from Durham University, England, in 1998 had been recovered after being submitted for valuation at the Folger Shakespeare Library. News reports estimated the folio's value at anywhere from £250,000 in total for the First Folio and all the other books and manuscripts stolen (BBC News, 1998), up to $30 million (New York Times, 2008).[57] Although the book, once the property of John Cosin the Bishop of Durham, was returned to the library, it had been mutilated and was missing its cover and title page.[58] The folio was returned to public display on 19 June 2010 after its twelve-year absence.[59] Fifty-three-year-old Raymond Scott received an eight-year prison sentence for handling stolen goods, but was acquitted of the theft itself.[60] A July 2010 BBC programme about the affair, Stealing Shakespeare, portrayed Scott as a fantasist and petty thief.[61] In 2013, Scott killed himself in his prison cell.[62]

In November 2014, a previously unknown First Folio was found in a public library in Saint-Omer, Pas-de-Calais in France, where it had lain for 200 years.[37][63] Confirmation of its authenticity came from Eric Rasmussen, of the University of Nevada, Reno, one of the world's foremost authorities on Shakespeare.[37][63] The title page and introductory material are missing.[63][64] The name "Neville", written on the first surviving page, may indicate that it once belonged to Edward Scarisbrick, who fled England due to anti-Catholic repression, attended the Jesuit Saint-Omer College, and was known to use that alias.[37] The only other known copy of a First Folio in France is in the National Library in Paris.[64]

In March 2016, Christie's announced that a previously unrecorded copy once owned by 19th-century collector Sir George Augustus Shuckburgh-Evelyn would be auctioned on 25 May 2016.[65]

In April 2016 another new discovery was announced, a First Folio having been found in Mount Stuart House on the Isle of Bute, Scotland. It was authenticated by Professor Emma Smith of Oxford University.[66] The Folio originally belonged to Isaac Reed.[67]

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ More generally, the term first folio is employed in other appropriate contexts, as in connection with the first folio collection of Ben Jonson's works (1616), or the first folio collection of the plays in the Beaumont and Fletcher canon (1647).

- ↑ Dates follow the Julian calendar, used in England throughout Shakespeare's lifespan, but with the start of the year adjusted to 1 January (see Old Style and New Style dates). Under the Gregorian calendar, adopted in Catholic countries in 1582, Shakespeare died on 3 May.[2]

- ↑ The exact years of his London career are unknown, but biographers suggest that it may have begun any time from the mid-1580s to just before Robert Greene mentions Shakespeare in his Groats-Worth of Wit.[3][4][5]

- ↑ There is a tradition, first recorded by Nicholas Rowe and repeated by Johnson, that Shakespeare retired to Stratford "some years before his death".[6] Retirement from all work was uncommon, however, and modern biographers generally do not accord this tradition a lot of weight.[7] But after 1610, Shakespeare wrote fewer plays, and none are attributed to him after 1613.[8] His last three plays were collaborations, probably with John Fletcher,[9] who succeeded him as the house playwright of the King's Men.[10]

- ↑ By 1623, Shakespeare’s works had been printed in 95 editions. The closest competitors were Thomas Dekker (56), Thomas Middleton (43), and Ben Jonson (24).[11]

- ↑ Where Chaucer, Spenser, and Beaumont were buried, and where Shakespeare's contemporaries like Ben Jonson would later be either buried or memorialised.

- ↑ Stephen Greenblatt, in an article for The New York Review of Books, points to the difference in social status: "A grand aristocrat … could [not readily] show a connection to a social nonentity—a bourgeois entrepreneur and playwright without Oxbridge honors or family distinction …."[15]

- ↑ Edward Fairfax's translation of Torquato Tasso's Godfrey of Bulloigne (1600), Thomas Heywood's Troia Britanica (1609), and Boccaccio’s Decameron (1620) was published in folio by William and Isaac Jaggard; Montaigne’s Essays (1603, 1613), Samuel Daniel’s Panegyricke Congratulatory (1603), Lucan’s Pharsalia (1614), and James Mabbe's translation of Mateo Alemán’s The Rogue (1623) were published by Edward Blount; and John Smethwick published Ben Jonson's Works (1616), and Michael Drayton's Poems (1619). All told, a quarter of the literary folios produced in London between 1600 and 1623 were the work of these three publishers.[22]

- ↑ He also cites previous estimates from Anthony James West, based in part on unpublished estimates by Peter Blayney, that the publisher's cost was about 6s 8d (equivalent to £56 in 2016), and the wholesale price no more than 10s (equivalent to £84 in 2016).[36]

References

- ↑ The Guardian 2015.

- ↑ Schoenbaum 1987, p. xv.

- ↑ Wells 2006, p. 28.

- ↑ Schoenbaum 1987, pp. 144–146.

- ↑ Chambers 1930, p. 59.

- ↑ Ackroyd 2006, p. 476.

- ↑ Honan 1998, pp. 382–383.

- ↑ Schoenbaum 1987, p. 279.

- ↑ Honan 1998, pp. 375–378.

- ↑ Schoenbaum 1987, p. 276.

- 1 2 Rasmussen 2016, p. 23.

- ↑ Greenblatt 2005, p. 11.

- ↑ Bevington 2002, pp. 1–3.

- ↑ Wells 1997, p. 399.

- 1 2 Greenblatt 2016.

- 1 2 3 Lyons 2016, p. 6.

- 1 2 3 Lyons 2016, pp. 2–3.

- ↑ Lyons 2016, p. 10.

- 1 2 Lyons 2016, p. 7.

- 1 2 Lyons 2016, p. 8.

- ↑ Lyons 2016, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Rasmussen 2016, p. 26.

- ↑ Lyons 2016, p. 1.

- ↑ Edmondson 2015, pp. 321–323.

- ↑ Erne 2013, p. 26.

- ↑ Higgins 2016, p. 41.

- ↑ Higgins 2016, p. 42–44.

- ↑ Smith 1939, pp. 257–264.

- ↑ Evans 1974.

- ↑ Halliday 1964.

- ↑ Halliday 1964, p. 113.

- ↑ Halliday 1964, p. 390.

- ↑ Halliday 1964, p. 319.

- ↑ Moston 1995, p. vii.

- ↑ Tucker 2002.

- 1 2 Mayer 2016, p. 105.

- 1 2 3 4 Schuessler 2014.

- ↑ The Guardian 2016.

- ↑ Folgerpedia n.d.

- ↑ Vincent 2016.

- ↑ BBC 2011.

- ↑ Meisei University n.d.

- ↑ Farber 2013.

- ↑ West 2003, p. 222.

- ↑ West 2003, p. 204.

- ↑ Rasmussen & West 2012, p. 721.

- ↑ Rasmussen & West 2012, p. 585.

- ↑ https://www.huffingtonpost.com/regina-fraser-and-pat-johnson/an-extraordinary-library-_2_b_8210410.html

- ↑ Rasmussen & West 2012, p. 757.

- ↑ Rasmussen & West 2012, p. 230-240.

- ↑ Rasmussen & West 2012, pp. 770–771.

- ↑ Rasmussen & West 2012, pp. 851–854.

- ↑ Rasmussen & West 2012, pp. 772–773.

- ↑ Christie's 2001.

- ↑ Fessenden 2016.

- ↑ Iggulden 2006.

- ↑ Collins 2008.

- ↑ Wainwright 2010.

- ↑ Macknight 2010.

- ↑ Rasmussen 2011, p. 43.

- ↑ Rees 2010.

- ↑ BBC 2013.

- 1 2 3 BBC 2014.

- 1 2 Mulholland 2014.

- ↑ Finnigan 2016.

- ↑ Coughlan 2016.

- ↑ Smith 2016.

Bibliography

- Ackroyd, Peter (2006). Shakespeare: The Biography. London: Vintage. ISBN 978-0-7493-8655-9.

- "Rare Shakespeare folio goes on display in Skipton". BBC News. 21 March 2011. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- "Shakespeare folio dealer Raymond Scott killed himself". BBC News. 9 December 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- "Shakespeare Folio found in French library". BBC News. 26 November 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- Bevington, David (2002). Shakespeare. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-22719-9.

- Chambers, E. K. (1930). William Shakespeare: A Study of Facts and Problems. I. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-811774-4. OCLC 353406.

- "Wliiam Shakespeare's First Folio Sells for $6,166,000 at Christie's New York, Establishing a World Auction Record for any 17th Century Book" (Press release). Christie's. 8 October 2001. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- Collins, Paul (17 July 2008). "Folioed Again: Why Shakespeare is the world's worst stolen treasure". Slate. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- Coughlan, Sean (7 April 2016). "Shakespeare First Folio discovered on Scottish island". BBC News. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- Edmondson, Paul (2015). "His editors John Heminges and Henry Condell". In Edmondson, Paul; Wells, Stanley. The Shakespeare Circle: An Alternative Biography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 315–328. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107286580.030. ISBN 9781107286580 – via Cambridge Core.

- Erne, Lukas (2013). Shakespeare as Literary Dramatist (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139342445. ISBN 9781139342445 – via Cambridge Core.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1974). The Riverside Shakespeare. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 9780395044025.

- Farber, Robert D. (3 October 2013). "Shakespeare collection". Brandeis Special Collections Spotlight. Brandeis University. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- Fessenden, Marissa (7 January 2016). "Shakespeare's First Folio Goes on Tour in the U.S." Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- Finnigan, Lexi (17 March 2016). "'Holy Grail' of Shakespeare's first Four Folios set to go on sale in London". The Telegraph. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- "First Folios at the Folger". Folgerpedia. Folger Shakespeare Library. n.d. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- Greenblatt, Stephen (2005). Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare. London: Pimlico. ISBN 9780712600989.

- Greenblatt, Stephen (21 April 2016). "How Shakespeare Lives Now". The New York Review of Books. Vol. 63 no. 7. ISSN 0028-7504. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- "Ten books that changed the world". The Guardian. 7 August 2015. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- "Shakespeare first folio discovered at stately home on Scottish island". The Guardian. 7 April 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- Halliday, F. E. (1964). A Shakespeare Companion 1564–1964. Baltimore: Penguin. LCCN 64005260. OCLC 683393. OL 16529592M.

- Higgins, B.D.R. (2016). "Printing the First Folio". In Smith, Emma. The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare's First Folio. Cambridge Companions to Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 30–47. doi:10.1017/CCO9781316162552.004. ISBN 9781316162552 – via Cambridge Core. (Subscription required (help)).

- Honan, Park (1998). Shakespeare: A Life. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198117926.

- Iggulden, Amy (14 July 2006). "Shakespeare First Folio sells for £2.8m". The Telegraph. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- Lyons, Tara L. (2016). "Shakespeare in Print Before 1623". In Smith, Emma. The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare's First Folio. Cambridge Companions to Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–17. doi:10.1017/CCO9781316162552.002. ISBN 9781316162552 – via Cambridge Core. (Subscription required (help)).

- Macknight, Hugh (18 June 2010). "Stolen Shakespeare folio is given its day in court". The Independent. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- Mayer, Jean-Christophe (2016). "Early Buyers and Readers". In Smith, Emma. The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare's First Folio. Cambridge Companions to Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 103–119. doi:10.1017/CCO9781316162552.008. ISBN 9781316162552 – via Cambridge Core. (Subscription required (help)).

- "Meisei University Shakespeare Collection Database". Meisei University. n.d. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- Moston, Doug (1995). Introduction. The First Folio of Shakespeare, 1623. By Shakespeare, William. Applause Books. pp. ix–lix. ISBN 9781557831842.

- Mulholland, Rory (25 November 2014). "Shakespeare First Folio discovered in French library". The Telegraph. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- Rasmussen, Eric (2011). The Shakespeare Thefts: In Search of the First Folios. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9780230341203.

- Rasmussen, Eric (2016). "Publishing the First Folio". In Smith, Emma. The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare's First Folio. Cambridge Companions to Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 18–29. doi:10.1017/CCO9781316162552.003. ISBN 9781316162552 – via Cambridge Core. (Subscription required (help)).

- Rasmussen, Eric; West, Anthony James, eds. (2012). The Shakespeare First Folios: A Descriptive Catalogue. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780230517653.

- Rees, Jasper (30 July 2010). "Stealing Shakespeare, BBC One: Dodgy dealer, dodgy documentary". The Arts Desk. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- Schuessler, Jennifer (25 November 2014). "Shakespeare Folio Discovered in France". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- Smith, Emma (6 April 2016). "Vamped till ready". The Times Literary Supplement. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- Smith, Robert M. (1939). "Why a First Folio Shakespeare Remained in England". The Review of English Studies. Oxford University Press. 15 (59): 257–264. doi:10.1093/res/os-XV.59.257. eISSN 1471-6968. ISSN 0034-6551. JSTOR 509788 – via JSTOR. (Subscription required (help)).

- Tucker, Patrick (2002). Secrets of Acting Shakespeare: The Original Approach. Routledge. ISBN 9780878301485.

- Vincent, Helen (20 April 2016). "Shakespeare's First Folio". National Library of Scotland. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- Wainwright, Martin (9 July 2010). "Raymond Scott guilty of handling stolen folio of Shakespeare's plays". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- West, Anthony James (2003). A New World Census of First Folios. The Shakespeare First Folio: The History of the Book. II. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198187684.

Further reading

- Blayney, Peter W. M. (1991). The First Folio of Shakespeare. Washington: Folger Shakespeare Library. ISBN 9780962925436.

- Greg, W. W. (1955). The Shakespeare First Folio: Its Bibliographical and Textual History. Oxford: Clarendon Press. hdl:2027/mdp.39015016411061. OCLC 580880.

- Hinman, Charlton (1963). The Printing and Proof-Reading of the First Folio. Oxford: Clarendon Press. hdl:2027/mdp.39015002186073. ISBN 9780198116134. OCLC 164878968.

- Pollard, Alfred W. (1923). The Foundations of Shakespeare's Text. London: Oxford University Press. hdl:2027/mdp.39015024389275. OL 7040376M.

- Schoenbaum, S. (1987). William Shakespeare: A Compact Documentary Life (Revised ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505161-0.

- Walker, Alice (1953). Textual Problems of the First Folio: Richard III, King Lear, Troilus & Cressida, 2 Henry IV, Hamlet, Othello. Shakespeare problems. 7. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. hdl:2027/mdp.39015015376612. OCLC 1017312216.

- Wells, Stanley (1997). Shakespeare: A Life in Drama. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-31562-2.

- Wells, Stanley (2006). Shakespeare & Co. New York: Pantheon. ISBN 0-375-42494-6.

- Willoughby, Edwin Eliott (1932). The Printing of the First Folio of Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. hdl:2027/uc1.32106005244717. OCLC 2163079. OL 6285205M.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to First Folio. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

General resources

Digital facsimiles

- West 31—The Bodleian Library's First Folio

- West 150—The Boston Public Library's First Folio, digitized by the Internet Archive

- The Internet Shakespeare Editions

- West 153—Brandeis University's First Folio, digitized for the Internet Shakespeare Editions project

- West 192—The State Library of New South Wales's First Folio, digitized for the Internet Shakespeare Editions project

- West 6—The University of Cambridge's First Folio

- Folger Shakespeare Library

- West 216—The Bodmer Library's First Folio

- West 185—The Harry Ransom Center's First Folio

- West 12—The Brotherton Library's First Folio

- West 201—Meisei University's First Folio

- West 174—Miami University's First Folio

- West 192—The State Library of New South Wales's First Folio

- West 180—The Furness Library's First Folio

- Unnumbered—The Bibliothèque d’agglomération de Saint-Omer's First Folio (discovered in 2016, after the West census)

- West 197—The Württembergische Landesbibliothek's First Folio

.png)