Falles

.jpg)

The Falles (Valencian: Falles, sing. Falla; Spanish: Fallas) is a traditional celebration held in commemoration of Saint Joseph in the city of Valencia, Spain. The term Falles refers to both the celebration and the monuments burnt during the celebration.[1] A number of towns in the Valencian Community have similar celebrations inspired by the original Falles de València celebration. The Falles festival was added to UNESCO's intangible cultural heritage of humanity list on 30 November 2016.[2]

Each neighbourhood of the city has an organised group of people, the Casal faller, that works all year long holding fundraising parties and dinners, usually featuring the noted dish, paella,[3] a specialty of the region. Each casal faller produces a construction known as a falla which is eventually burnt. A casal faller is also known as a comissió fallera and currently there are approximately 400 registered in Valencia.[4][5]

Etymology

The name of the festival is the plural of the Valencian word falla. The word's derivation is as follows:

- Latin fax "torch" → Latin facvla (diminutive) → Vulgar Latin *facla → Valencian falla.

Falles and ninots

Formerly, much time would be spent by the casal faller preparing the ninots (Valencian for puppets or dolls).[6] During the four days leading up to 19 March, each group takes its ninot out for a grand parade, and then mounts it, each on its own elaborate firecracker-filled cardboard and paper-mâché artistic monument in a street of the given neighbourhood. This whole assembly is a falla.

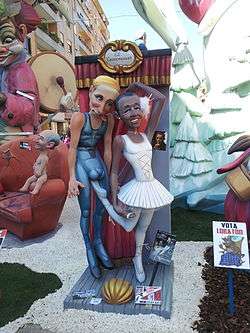

The ninots and their falles are constructed according to an agreed-upon theme that has traditionally been a satirical jab at whatever draws the attention of the fallers (the registered participants of the casals).[6] In modern times, the two-week-long festival has spawned a substantial local industry, to the point that an entire suburban area has been designated the Ciutat fallera (Falles City). Here, crews of artists and artisans, sculptors, painters, and other craftsmen, all spend months producing elaborate constructions of paper and wax, wood and polystyrene foam tableaux towering up to five stories, composed of fanciful figures, often caricatures, in provocative poses arranged in a gravity-defying manner.[7] Each of them is produced under the direction of one of the many individual neighbourhood casals fallers who vie with each other to attract the best artists, and then to create the most outrageous allegorical monument to their target. There are about 750 of these neighbourhood associations in Valencia,[6] with over 200,000 members, or a quarter of the city's population.[8]

During Falles, many people wear their casal faller dress of regional and historical costumes from different eras of València's history. The dolçaina (an oboe-like reed instrument) and tabalet (a kind of Valencian drum) are frequently heard,[9] as most of the different casals fallers have their own traditional bands.

Although the Falles is a very traditional event and many participants dress in medieval clothing, the ninots for 2005 included such modern characters as Shrek and George W. Bush, and the 2012 Falles included characters like Barack Obama and Lady Gaga.

Events during Falles

The five days and nights of Falles might be described as a continuous street party. There are a multitude of processions: historical, religious, and comedic. Crowds in the restaurants spill out into the streets. Explosions can be heard all day long and sporadically through the night. Everyone from small children to elderly people can be seen throwing fireworks and noisemakers in the streets, which are littered with pyrotechnical debris. The timing of the events is fixed, and they fall on the same date every year, though there has been discussion about holding some events on the weekend preceding the Falles, to take greater advantage of the tourist potential of the festival[10] or changing the end date in years where it is due to occur in midweek.[11]

La Despertà

Each day of Falles begins at 8:00 am with La Despertà ("the wake-up call").[12] Brass bands appear from the casals and begin to march down every street playing lively music. Close behind them are the fallers, throwing large firecrackers in the street as they go.

La Mascletà

The Mascletà, an explosive barrage of coordinated firecracker and fireworks displays, takes place at 2:00 pm every day of the festival;[12] the main event is the municipal Mascletà in the Plaça de l'Ajuntament where the pyrotechnicians compete for the honour of providing the final Mascletà of the festes (on 19 March). At 2:00 pm the clock chimes and the Fallera Major, dressed in her fallera finery, will call from the balcony of City Hall, Senyor/a pirotècnic/a, pot començar la mascletà! ("Mr./Ms. Pyrotechnic, you may commence the Mascletà!"), and the Mascletà begins.

The Mascletà is almost unique to the Valencian Community, and very popular with the Valencian people. Smaller neighbourhoods often hold their own mascletà for saint's days, weddings and other celebrations.

A nighttime variant runs in the evening hours by the same pyrotechnicans that were present in the afternoon.

La Plantà

On the day of the 15th, all of the falles infantils are to be finished being constructed, and later that night all of the falles majors (big Falles) are to be completed.[12] If not, they face disqualification.

L'Ofrena de flors

In this event, the flower offering, each of the casals fallers takes an offering of flowers to the Virgin Mary as Our Lady of the Forsaken.[12] This occurs all day during 17–18 March. A statue of the Virgin Mary and its large pedestal are then covered with all the flowers.

Els Castells and La Nit del Foc

On the nights of the 15, 16, 17, and 18th there are firework displays in the old riverbed in València. Each night is progressively grander and the last is called La Nit del Foc (the Night of Fire).[12]

Cavalcada del Foc

On the final evening of Falles, at 7:00 pm on March 19, a parade known in Valencian as the Cavalcada del Foc (the Fire Parade) takes place along Colon street and Porta de la Mar square. This spectacular celebration of fire, the symbol of the fiesta’s spirit, is the grand finale of Falles and a colourful, noisy event featuring exhibitions of the varied rites and displays from around the world which use fire; it incorporates floats, giant mechanisms, people in costumes, rockets, gunpowder, street performances and music.

La Cremà

On the final night of Falles, around midnight on March 19,[13] these falles are burnt as huge bonfires. This is known as La Cremà (the Burning), the climax of the whole event,[14] and the reason why the constructions are called falles ("torches"). Traditionally, the falla in the Plaça de l'Ajuntament is burned last.

All casals have a falla infantil (a children's falla, smaller and without satirical themes), which is held a few metres away from the main one. This is burnt first, at 10:00 pm. The main neighbourhood falles are burnt closer to midnight; the burning of the falles in the city centre often starts later. For example, in 2005, the fire brigade delayed the burning of the Egyptian funeral falla in Carrer del Convent de Jerusalem until 1:30 am, when they were sure all safety concerns were addressed.

Each falla is laden with fireworks which are lit first. The construction itself is lit either after or during the explosion of these fireworks. Falles burn quite quickly, and the heat given off is felt by all around. The heat from the larger ones often drives the crowd back a couple of metres, even though they are already behind barriers that the fire brigade has set several metres from the construction. In narrower streets, the heat scorches the surrounding buildings, and the firemen douse the fronteres, window blinds, street signs, etc. with their hoses to stop them catching fire or melting, from the beginning of the cremà until it cools down.

Away from the falles, people frolic in the streets, the whole city resembling an open-air dance party, except that instead of music there is the incessant (and occasionally deafening) sound of people throwing fireworks around randomly. There are many stalls selling trinkets and snacks such as the typical fried porres, churros and bunyols, as well as roasted chestnuts.

While the smaller fallas dotted around the streets are burned at approximately the same time, the last falla to be burned is the main one, which is saved until last so that everybody can watch it. This main falla is found outside the Ajuntament – the town hall. People arrive a few hours before the scheduled burning time to get a front row view.

History

There are different conjectures regarding the origin of the Falles festival. One suggests that the Falles started in the Middle Ages, when artisans disposed of the broken artefacts and pieces of wood they saved during the winter by burning them to celebrate the spring equinox. Valencian carpenters used planks of wood called parots to hang their candles on during the winter, as these were needed to provide light to work by. With the coming of the spring, they were no longer necessary, so they were burned.[15] Over time, and with the intervention of the Church, the date of the burning of these parots was made to coincide with the celebration of the festival of Saint Joseph, the patron saint of carpenters.[16]

This tradition continued to evolve. The parot was dressed with clothing so that it looked like a person; features identifiable with some well-known person from the neighbourhood were often added as well. To collect these materials, children went from house to house asking for una estoreta velleta (an old rug) to add to the parot. This became a popular song that the children sang as they gathered all sorts of old flammable furniture and utensils to burn in the bonfire with the parot. These parots were the first ninots. Over the years, people of the neighbourhoods began to organise the building of the falles, and thus the typically intricate constructions, including their various figures, were born.

Until the beginning of the 20th century, the falles were tall boxes with three or four wax dolls dressed in fabric clothing. This changed when the creators began to use cardboard. The fabrication of the falles continues to evolve in modern times, when the largest displays are made of polystyrene and soft cork easily molded with hot saws. These techniques have allowed the creation of falles over 30 metres high.

The origin of the pagan festival is similar to that of the Bonfires of Saint John celebrated in the Alacant region, in the sense that both came from the Latin custom of lighting fires to welcome spring. In València, this ancient tradition led to the burning of accumulated waste, particularly wood, at the end of winter on the feast day of Saint Joseph. Given the reputed humorous character of Valencians, it was natural that the people began to burn figurines depicting persons and events of the past year. The burning symbolised liberation from living in servitude to the memory of these events or else represented humorous and often critical commentary on them. The festival thus evolved a more satirical and ironic character, and the wooden castoffs gradually came to be assembled into progressively more elaborate 'monuments' that were designed and painted in advance.

In the early 20th century, and especially during the Spanish Civil War, the monuments became more anti-clerical in nature and were often highly critical of the local or national governments,[17] which tried to ban the Falles many times, without success. Under the dictatorship of Francisco Franco the celebration lost much of its satirical nature because of government censorship, but the monuments were among the few fervent public expressions allowed then, and they could be made freely in València. During this period, many religious customs such as the offering of flowers to Mare de Déu dels Desamparats (Our Lady of the Forsaken) were taken up, which today are essential parts of the festival, even though they were unrelated to the original purpose of the celebration.

With the restoration of democracy and the end of government censorship, the critical falles reappeared, and obscene satirical ones with them. Despite thirty years of freedom of expression, the world view of the fallero can still be socially conservative, is often sexist and may involve some of the amoralism of Valencian politics. This has sometimes led to criticism by certain cultural critics, environmentalists, and progressives. Yet there are celebrants of all ideologies and factions, and they have different interpretations of the spirit of the celebration. Although recent initiatives such as the pilota championships, literary competitions and other events have broadened its cultural expression, the city still embraces such ancient traditions to express its own singular identity.[18]

Secció Especial

The Secció Especial is a group of the largest and most prestigious falles commissions in the city of Valencia. In 2007, the group consisted of 14 commissions. This class of falles was first started in 1942 and originally included the falles of Barques, Reina-Pau and Plaça del Mercat. Currently, none of these are still in the group. The commission that has most often participated in this group as of 2015 was Na Jordana, with 62 times. The Secció Especial awards the prizes with the exception of the one awarded by the town hall; winning the first prize in the Secció Especial is the most prestigious prize any falla can win. All other falles fall into different classes (18 as of 2017) determined by the amount of money invested in each falla.

- Recent winners of Secció Especial

.jpg) 2006: Nou Campanar

2006: Nou Campanar 2007: Nou Campanar

2007: Nou Campanar 2008: Nou Campanar

2008: Nou Campanar- 2009: Nou Campanar

2010: Convent Jerusalem-Matemàtic Marzal

2010: Convent Jerusalem-Matemàtic Marzal- 2011: Convent Jerusalem-Matemàtic Marzal

- 2012: Nou Campanar

2013: Convent Jerusalem-Matemàtic Marzal

2013: Convent Jerusalem-Matemàtic Marzal- 2014: Plaza del Pilar.

2015: Plaza del Pilar

2015: Plaza del Pilar 2016: Cuba-Literato Azorín.

2016: Cuba-Literato Azorín. 2017: L'Antiga de Campanar.

2017: L'Antiga de Campanar. 2018: Convent Jerusalem-Matemàtic Marzal

2018: Convent Jerusalem-Matemàtic Marzal

See also

Falles gallery

- 2005

View down street

View down street Falleres and fallers merrily beating drums

Falleres and fallers merrily beating drums Paella being cooked on a wood fire in the middle of the road

Paella being cooked on a wood fire in the middle of the road Falla with painter and fat woman. This was as high as a building.

Falla with painter and fat woman. This was as high as a building. Part of falla with Egyptian funeral procession. In Carrer del Convent de Jerusalem. 2nd prize, special section, Falles 2005.

Part of falla with Egyptian funeral procession. In Carrer del Convent de Jerusalem. 2nd prize, special section, Falles 2005.

- 2008

Falla in Nou Campanar

Falla in Nou Campanar The children's falla in carrer Poeta Altet

The children's falla in carrer Poeta Altet The same falla with fireworks going off

The same falla with fireworks going off The same falla blazing

The same falla blazing The monumental Egyptian falla, just as the frame of its tallest tower collapses

The monumental Egyptian falla, just as the frame of its tallest tower collapses Falla in the Convento de Jerusalén Street

Falla in the Convento de Jerusalén Street Falla in the Pilar's Square

Falla in the Pilar's Square- Twilight street of Sueca-Literato Azorín

- 2010

Falla Literato Azorín lightning

Falla Literato Azorín lightning

- 2017

Falla Almirante Cadarso-Conde Altea (5th prize)

Falla Almirante Cadarso-Conde Altea (5th prize) Falla Na Jordana (7th prize)

Falla Na Jordana (7th prize) Falla Convento Jerusalen Matematico Marzal (3rd prize)

Falla Convento Jerusalen Matematico Marzal (3rd prize)

References

- ↑ Martin, Charles B. (March 1973). "The Fallas: A Folk Festival of Valencia". The Journal of Popular Culture. 6 (4): 854. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.1973.00854.x.

- ↑ "Valencia Fallas festivity included in UNESCO's intangible cultural heritage list". EPA European Pressphoto Agency b.v. European Pressphoto Agency. November 30, 2016. Archived from the original on December 1, 2016. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ↑ Hazel Andrews; Teresa Leopold (8 February 2013). Events and the Social Sciences. Routledge. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-415-60560-1.

- ↑ Gil-Manuel Hernàndez i Martí (1 January 1996). Falles i franquisme a València. Afers. p. 92. ISBN 978-84-86574-36-9.

- ↑ "Fallas - Comisiones por número de censo". 16 February 2016.

- 1 2 3 Xavier Costa (2006). "Festivity and the Sacred: The Symbolic Universe in the Festival of the 'Fallas' of Saint Joseph". In Elisabeth Arweck; William J. F. Keenan. Materializing Religion: Expression, Performance and Ritual. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-0-7546-5094-2.

- ↑ "El atractivo turístico de la Ciutat Fallera". El País (in Spanish) (València). Ediciones El País, S.L. 5 March 2014. Archived from the original on October 31, 2015.

- ↑ Greg Richards (7 March 2013). "The Festivalization of Society or the Socialization of Festivals?". In Greg Richards. Cultural Tourism: Global and Local Perspectives. Routledge. p. 271. ISBN 978-1-136-79234-2.

- ↑ Antonio Ariño Villarroya (1 January 1992). La ciudad ritual: la fiesta de las Fallas. Anthropos Editorial. p. 60. ISBN 978-84-7658-368-5.

- ↑ Fin de fiesta de unas Fallas perfectas, ABC.es, 20 March 2012

- ↑ Los hosteleros quieren ´más´ Fallas, Levante, 20 March 2012

- 1 2 3 4 5 Encarnación Galindo García (30 July 2014). Las fallas de Valencia: Mucho más que un sueño. Cambridge University Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-84-9848-049-8.

- ↑ Carol Styles Carvajal; Jane Horwood; Nicholas Rollin (2004). Concise Oxford Spanish Dictionary: Spanish-English/English-Spanish. Oxford University Press. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-19-860977-3.

- ↑ Antonio Ariño (1999). El Teatre en la festa valenciana. Generalitat Valenciana. p. 328. ISBN 978-84-482-2333-5.

- ↑ Eamonn Rodgers (11 March 2002). Encyclopedia of Contemporary Spanish Culture. Routledge. p. 174. ISBN 978-1-134-78858-3.

- ↑ Irwin Altman; Setha M. Low (6 December 2012). Place Attachment. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 217. ISBN 978-1-4684-8753-4.

- ↑ La Valencia de los años 30: entre el paraíso y el infierno. Carena Editors, S.l. 1999. p. 207. ISBN 978-84-87398-35-3.

- ↑ "Villarroya 1992, p. 13

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Falles. |

- Official page for the Fallas Festival

- Official page for the Fallas Festival Organizing Committee

- Fallas Festival (in Spanish, Valencian, English, French and German)

- Promotional video of the Fallas Festival 2011

- Explanation of all the Fallas events in English

- iPhone/iPod App for Las Fallas

- The Fallas in Valencia: The Beauty of Fire

.svg.png)