Faithless elector

In United States presidential elections, a faithless elector is a member of the United States Electoral College who does not vote for the presidential or vice-presidential candidate for whom they had pledged to vote. That is, they break faith with the candidate they were pledged to and vote for another candidate, or fail to vote. A pledged elector is only considered a faithless elector by breaking their pledge; unpledged electors have no pledge to break.

Electors are typically chosen and nominated by a political party or the party's presidential nominee: they are usually party members with a reputation for high loyalty to the party and its chosen candidate. Thus, a faithless elector runs the risk of party censure and political retaliation from their party, as well as potential legal penalties in some states. Candidates for elector are nominated by state political parties in the months prior to Election Day.

In some states, including Indiana, the electors are nominated in primaries, the same way other candidates are nominated.[2] In other states, such as Oklahoma, Virginia, and North Carolina, electors are nominated in party conventions. In Pennsylvania, the campaign committee of each candidate names their candidates for elector (an attempt to discourage faithless electors). The parties have generally been successful in keeping their electors faithful, leaving out the cases in which a candidate died before the elector was able to cast a vote.

During the 1836 election, Virginia's entire 23-man electoral delegation faithlessly abstained[3] from voting for victorious Democratic vice presidential nominee Richard M. Johnson.[4] The loss of Virginia's support caused Johnson to fall one electoral vote short of a majority, causing the vice presidential election to be thrown into the U.S. Senate for the only time in American history. The presidential election itself was not in dispute because Virginia's electors voted for Democratic presidential nominee Martin Van Buren as pledged. The U.S. Senate ultimately elected Johnson as vice president after a party-line vote.

There have been a total of 167[5] instances of faithlessness as of 2016. Nearly all have voted for third party candidates or non-candidates, as opposed to switching their support to a major opposing candidate. Ultimately, faithless electors have only impacted the outcome of an election once, during the 1796 election where Pinckney would have become the President and Adams the Vice-President.[6]

The United States Constitution does not specify a notion of pledging; no federal law or constitutional statute binds an elector's vote to anything. All pledging laws originate at the state level.[7][8]

Legal position

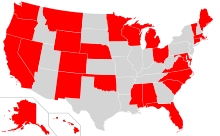

Twenty-one states do not have laws compelling their electors to vote for a pledged candidate.[9] Twenty-nine states plus the District of Columbia have laws to penalize faithless electors, although these have never been enforced.[4] In lieu of penalizing a faithless elector, some states, such as Michigan and Minnesota, specify the faithless elector's vote is void.[10] Minnesota invoked this law for the first time in 2016 when an elector pledged to Hillary Clinton attempted to vote for Bernie Sanders instead.[11]

Until 2008, Minnesota's electors cast secret ballots. Although the final count would reveal the occurrence of faithless votes (except in the unlikely case of two or more changes canceling out), it was impossible to determine which elector(s) were faithless. After an unknown elector was faithless in 2004, Minnesota amended its law to require public balloting of the electors' votes and invalidate any vote cast for someone other than the candidate to whom the elector was pledged.[12] After an elector has voted, their vote can be changed only in states such as Colorado, Michigan and Minnesota, which invalidate votes other than those pledged. In the twenty-nine states with laws against faithless electors, a faithless elector may only be punished after they vote.

U.S. Supreme Court

The constitutionality of state pledge laws was confirmed by the Supreme Court in 1952 in Ray v. Blair[13] in a 5–2 vote. The court ruled states have the right to require electors to pledge to vote for the candidate whom their party supports, and the right to remove potential electors who refuse to pledge prior to the election. The court also wrote:[13]

However, even if such promises of candidates for the electoral college are legally unenforceable because violative of an assumed constitutional freedom of the elector under the Constitution, Art. II, § 1, to vote as he may choose [emphasis added] in the electoral college, it would not follow that the requirement of a pledge in the primary is unconstitutional.

— U.S. Supreme Court, Ray v. Blair, 1952

The ruling only held that requiring a pledge, not a vote, was constitutional and Justice Jackson, joined by Justice Douglas, wrote in his dissent, "no one faithful to our history can deny that the plan originally contemplated what is implicit in its text – that electors would be free agents, to exercise an independent and nonpartisan judgment as to the men best qualified for the Nation's highest offices."[13] More recent legal scholars believe "a state law that would thwart a federal elector’s discretion at an extraordinary time when it reasonably must be exercised would clearly violate Article II and the Twelfth Amendment".[14]

The Supreme Court has never ruled on the constitutionality of state laws punishing or replacing electors for actually casting a faithless vote, or refusing to count said votes.[15]

History

Over 22 occasions, a total of 179 electors have not cast their votes for President or Vice President as prescribed by the legislature of the state they represented. Of those, 71 electors changed their votes because the candidate to whom they were pledged died before the electoral ballot (1872, 1912). Two electors chose to abstain from voting for any candidate (1812, 2000).[4] The remaining 106 were changed typically by the elector's personal preference, although there have been rare instances where the change may have been caused by an honest mistake. Usually, faithless electors act alone, although on occasion a faithless elector has attempted to induce other electors to change their votes in concert, usually with little if any success. An exception was the 1836 election, in which all 23 Virginia electors acted together.

The 1796 election is the only instance during which the faithless electors successfully changed the outcome of an election. During this election 18 electors pledged to the Federalist voted as pledged for John Adams, however they refused to voted for Pinckney.[6] As a result Adams attained 71 electoral votes, Jefferson received 68, and Pinckney received 59.[16] Had the 18 electors remained faithful Pinckney would have won the presidency with 77 electoral votes and Adams would have become his vice president.

In the 1836 Election faithless electors altered the outcome of the electoral college vote, but failed to change the outcome of the overall election. The Democratic ticket won states with 170 of the 294 electoral votes, but the 23 Virginia electors abstained in the vote for Vice President, so the Democratic nominee, Richard M. Johnson, got only 147 (exactly half), and was not elected. However, Johnson was elected Vice President by the U.S. Senate.

List of faithless electors

The following is a list of all faithless electors (in reverse chronological order). The number preceding each entry is the number of faithless electors for the given year.

2016

7 – 2016 election: In Washington, Democratic party electors gave three presidential votes to Colin Powell and one to Faith Spotted Eagle[17] and these electors cast vice-presidential votes for Elizabeth Warren, Maria Cantwell, Susan Collins, and Winona LaDuke. In Hawaii, Bernie Sanders received one presidential vote and Elizabeth Warren received one vice-presidential vote. In Texas, John Kasich and Ron Paul received one presidential vote each, and one of these electors gave Carly Fiorina a vice-presidential vote.[18][19]

In addition, three other electors attempted to vote against their pledge, but had their votes invalidated. In Colorado, Kasich received one vote for president, which was invalidated.[20] Two additional electors, one in Maine and one in Minnesota, cast votes for Sanders for president but had their votes invalidated and their replacement electors cast for Clinton. The same Minnesota elector voted for Tulsi Gabbard for vice president, but had that vote invalidated and given to Tim Kaine.

10 was the largest number to not vote for the pledged presidential candidate in US history.

2000 to 2004

1 – 2004 election: An anonymous Minnesota elector, pledged for Democrats John Kerry and John Edwards, cast his or her presidential vote for "John Ewards" [sic],[21] rather than Kerry, presumably by accident.[22] (All of Minnesota's electors cast their vice presidential ballots for John Edwards.) Minnesota's electors cast secret ballots, so the identity of the faithless elector is not known. As a result of this incident, Minnesota statutes were amended to provide for public balloting of the electors' votes and invalidation of a vote cast for someone other than the candidate to whom the elector is pledged.[12]

1 – 2000 election: Washington, D.C. elector Barbara Lett-Simmons, pledged for Democrats Al Gore and Joe Lieberman, cast no electoral votes as a protest of Washington D.C.'s lack of voting congressional representation.[15] Lett-Simmons's electoral college abstention, the first since 1864, was intended to protest what Lett-Simmons referred to as the federal district's "colonial status".[15] Lett-Simmons described her blank ballot as an act of civil disobedience, not an act of a faithless elector; Lett-Simmons supported Gore and would have voted for Gore if she had thought he had a chance to win.[15] This did not affect the outcome of the election.

1968 to 1996

1 – 1988 election: West Virginia Elector Margarette Leach, pledged for Democrats Michael Dukakis and Lloyd Bentsen, but as a form of protest against the winner-take-all custom of the Electoral College, instead cast her votes for the candidates in the reverse of their positions on the national ticket; her presidential vote went to Bentsen and her vice presidential vote to Dukakis.[23]

1 – 1976 election: Washington Elector Mike Padden, pledged for Republicans Gerald Ford and Bob Dole, cast his presidential electoral vote for Ronald Reagan, who had challenged Ford for the Republican nomination. He cast his vice presidential vote, as pledged, for Dole.[24]

1 – 1972 election: Virginia Elector Roger MacBride, pledged for Republicans Richard Nixon and Spiro Agnew, cast his electoral votes for Libertarian candidates John Hospers and Tonie Nathan. MacBride's VP vote for Nathan was the first electoral vote cast for a woman in U.S. history.[25]

1 – 1968 election: North Carolina Elector Lloyd W. Bailey, pledged for Republicans Richard Nixon and Spiro Agnew, cast his votes for American Independent Party candidates George Wallace and Curtis LeMay. Bailey later stated at a Senate hearing that he would have voted for Nixon and Agnew if his vote would have altered the outcome of the election.[26]

1912 to 1960

1 – 1960 election: Oklahoma Elector Henry D. Irwin, pledged for Republicans Richard Nixon and Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., contacted the other 218 Republican electors to convince them to cast presidential electoral votes for Democratic non-candidate Harry F. Byrd and vice presidential electoral votes for Republican Barry Goldwater, though most replied they had a moral obligation to vote for Nixon; Irwin voted for Byrd and Goldwater. Fourteen unpledged electors (eight from Mississippi and six from Alabama) also voted for Byrd for president, but supported Strom Thurmond for vice president - since they were not pledged to anyone, their action was not faithless.[27]

1 – 1956 election: Alabama Elector W. F. Turner, pledged for Democrats Adlai Stevenson and Estes Kefauver, cast his votes for circuit judge Walter Burgwyn Jones and Herman Talmadge.[27]

1 – 1948 election: Tennessee elector Preston Parks was on both the Democratic Party for Harry S. Truman and the States' Rights Democratic Party for Strom Thurmond. When the Democratic Party slate won, Parks voted for Thurmond and Fielding L. Wright.[27]

8 – 1912 election: Republican vice presidential candidate (and incumbent Vice President) James S. Sherman died before the popular election. Nicholas M. Butler was hastily designated to receive the electoral votes that would have gone to Sherman. The Republicans only carried two states with eight electoral votes between them. All eight Republican electors voted Butler for Vice President.

1872 to 1896

27 – 1896 election: The Democratic Party and the People's Party both ran William Jennings Bryan as their presidential candidate, but ran different candidates for Vice President. The Democratic Party nominated Arthur Sewall and the People’s Party nominated Thomas E. Watson. Although the Populist ticket did not win the popular vote in any state, 27 Democratic electors for Bryan cast their vice-presidential vote for Watson instead of Sewall.[28]

1 – 1892 election: In Oregon, the electors were pledged to vote for Benjamin Harrison; three electors voted for Harrison and one faithless elector voted for the third-party Populist candidate, James B. Weaver.[29]

63 – 1872 election: Horace Greeley was alive during the November election but died before the electoral vote. 63 out of 66 electors refused to vote for a deceased candidate, and out of those, 43 cast their presidential votes for four non-candidates, and 17 abstained. Greeley received three posthumous electoral votes, but these votes were disallowed by Congress.[30]

1812 to 1840

1 – 1840 election: One elector from Virginia, Arthur Smith of Isle of Wight County, was pledged to vote for Democratic candidates Martin Van Buren (for President) and Richard M. Johnson (for Vice President). However, he voted for James K. Polk for Vice President.[31]

23 – 1836 election: The 23 electors from Virginia were pledged to vote for Democratic candidates Martin Van Buren (for President) and Richard M. Johnson (for Vice President). However, they abstained from voting for Johnson, because of his open liaison with a slave mistress. This left Johnson with one fewer than a majority of electoral votes. Johnson was subsequently elected Vice President by the Senate.

32 – 1832 election: Two National Republican Party electors from the state of Maryland refused to vote for presidential candidate Henry Clay and did not cast a vote for him or for his running mate, John Sergeant. All 30 electors from Pennsylvania refused to support the Democratic vice presidential candidate Martin Van Buren, voting instead for William Wilkins.

7 – 1828 election: Seven of nine electors from Georgia refused to vote for vice presidential candidate John C. Calhoun. All seven cast their vice presidential votes for William Smith instead.

1 – 1820 election: William Plumer was pledged to vote for Democratic-Republican candidate James Monroe, but he cast his vote for John Quincy Adams, who was not a candidate in the election. Some historians contend Plumer wanted George Washington to be the only unanimous selection and that he further wanted to draw attention to his friend Adams as a potential candidate. These claims are disputed.[27] (Plumer cast his vice presidential vote for Richard Rush, not Daniel D. Tompkins.)

4 – 1812 election: Three electors pledged to vote for Federalist vice presidential candidate Jared Ingersoll voted for Democratic-Republican Elbridge Gerry. One Ohio elector did not vote.

Before 1812

6 – 1808 election: Six electors from New York were pledged to vote for Democratic-Republican James Madison for President and George Clinton for Vice President. Instead, they voted for Clinton to be President, with three voting for Madison for Vice President and the other three voting for James Monroe for Vice President.

19 – 1796 election: Samuel Miles, an elector from Pennsylvania, was pledged to vote for Federalist presidential candidate John Adams, but voted for Democratic-Republican candidate Thomas Jefferson. He cast his other presidential vote as pledged for Thomas Pinckney; there was no provision at the time for specifying president or vice president. An additional 18 electors voted for Adams as pledged, but refused to vote for Pinckney.[6] This was an attempt to foil Alexander Hamilton's rumored plan to elect Pinckney as President, and this resulted in the unintended outcome that Adams's opponent, Jefferson, was elected Vice President instead of Adams's running mate Pinckney. This was the only time in U.S. history that the president and vice president have been from different parties prior to 1864, and the only time the winners were from different tickets. After the 1800 election resulted in a deadlock, the Twelfth Amendment was ratified in 1804. It changed the election procedure so that instead of casting two votes of the same type, electors would make an explicit choice for president and vice president.

See also

References

- ↑ "THE ELECTORAL COLLEGE". National Conference of State Legislatures.

- ↑ "About the Electors". National Archives and Records Administration.

- ↑

Sabato, Larry J.; Ernst, Howard R. (May 14, 2014). Encyclopedia of American Political Parties and Elections. Infobase Publishing. p. 133. ISBN 978-1-4381-0994-7. Retrieved 2016-11-15.

in 1836...the Virginia electors abstained rather than vote for Democratic vice presidential nominee Richard Johnson

- 1 2 3 "Faithless Electors". FairVote.org. FairVote. Retrieved September 24, 2015.

- ↑ "Faithless Electors". Fair Vote.

- 1 2 3 Chernow, Ron. Alexander Hamilton. New York: Penguin, 2004. p. 514.

- ↑ Openshaw, Pamela Romney (2014). Promises Of The Constitution: Yesterday Today Tomorrow. BookBaby. p. 10.3. ASIN B00LEWCS4E.

- ↑ Ross, Tara (2017). The Indispensable Electoral College: How the Founders' Plan Saves Our Country from Mob Rule. Gateway Editions. p. 26. ASIN B072FK8W7X.

- ↑ "U. S. Electoral College: Who Are the Electors? How Do They Vote?".

- ↑ "Michigan Election Law Section 168.47". Legislature.mi.gov. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- ↑ "Minnesota electors align for Clinton; one replaced after voting for Sanders".

- 1 2 "208.08, 2008 Minnesota Statutes". Revisor.leg.state.mn.us. Retrieved May 5, 2009.

- 1 2 3 Ray v. Blair 343 U.S. 214 (1952)

- ↑ Sheppard, Stephen M. (May 21, 2015). "A Case For The Electoral College And For Its Faithless Elector" (PDF). Wisconsin Law Review. 2015 (1).

- 1 2 3 4 Stout, David (December 19, 2000). "The 43rd President: The Electoral College; The Electors Vote, and the Surprises Are Few". The New York Times. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

But it was Mr. Gore who suffered an erosion today. Lett-Simmons, a Gore elector from the District of Columbia, left her ballot blank to protest what she called the capital's "colonial status" – its lack of a voting representative in Congress.

- ↑ "Electoral College Box Scores 1789-1996".

- ↑ "Four Washington state electors break ranks and don't vote for Clinton". The Seattle Times. 2016-12-19. Retrieved 2016-12-19.

- ↑ Walsh, Sean Collins (2016-12-19). "All but 2 Texas members of the Electoral College choose Donald Trump". Statesman. Retrieved 2016-12-24.

- ↑ Neff, Blake. "Faithless Electors In Texas Vote For Ron Paul, John Kasich". DailyCaller. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ↑ Detrow, Scott. "Donald Trump Secures Electoral College Win, With Few Surprises". NPR. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ↑ "Vote for Edwards instead of Kerry shocks Minnesota electors". December 17, 2004. Archived from the original on December 17, 2004.

- ↑ "MPR: Minnesota elector gives Edwards a vote; Kerry gets other nine". News.minnesota.publicradio.org. Retrieved May 5, 2009.

- ↑ Johnson, Sharen Shaw (January 5, 1989). "CAPITAL LINE: [FINAL Edition]". USA Today. Retrieved February 11, 2016. (Subscription required (help)).

Even though Bensten sought the vice presidency, Margarette Leach of West Virginia voted for him to protest the Electoral College's winner-take-all custom.

- ↑ Edwards, George C. (2011). Why the Electoral College Is Bad for America: Second Edition.

- ↑ Boaz, David (2008). "Nathan, Toni (1923– )". In Hamowy, Ronald. The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; Cato Institute. p. 347. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n212. ISBN 978-1-4129-6580-4. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

- ↑ "Tales of the Unfaithful Electors: Dr. Lloyd W. Bailey". EC: The US Electoral College Web Zine. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- 1 2 3 4 Edwards, George (2004). Why the Electoral College Is Bad for America. Yale University Press.

- ↑ "Senate and House Secured; Republican control in the next Conress assured. The House of Representatives Repub- lican by More than Two – thirds Ma- jority – Possible Loss of a Repub- lican Senator from the State of Washington – Republicans and Pop- ulists Will Organize the Senate and Divide the Patronage". The New York Times. November 9, 1894. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on November 14, 2013. Retrieved 2013-11-13.

- ↑ "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 31, 2005.

- ↑ Niles National Register, Vol. LIX, December 5, 1840, page 217

External links

- List of Electors Bound by State Law and Pledges, as of November 2000

- "The Electoral College – "Faithless Electors"". Official website of the Center for Voting and Democracy. 2002. Retrieved December 5, 2006.

- "Faithless Electors". Website of FairVote, formerly the Center for Voting and Democracy. Retrieved May 13, 2017.