Fabry disease

| Fabry disease | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms | Fabry's disease, Anderson–Fabry disease, angiokeratoma corporis diffusum, alpha-galactosidase A deficiency |

| |

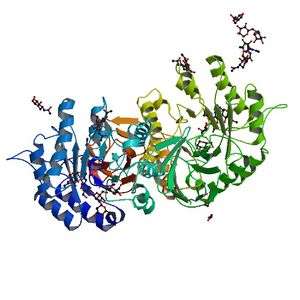

| Alpha galactosidase - the deficient protein in Fabry disease | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Endocrinology, cardiology, nephrology, dermatology |

| Complications | Heart failure, abnormal heart rhythms |

| Usual onset | Childhood |

| Causes | Genetic |

| Diagnostic method | Enzyme activity assay, genetic testing |

| Differential diagnosis | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy |

| Treatment | Enzyme replacement |

Fabry disease, also known as Anderson–Fabry disease, is a rare genetic disease that can affect many parts of the body including the kidneys, heart, and skin.[1] Fabry disease is one of a group of conditions known as lysosomal storage diseases. The genetic mutation that causes Fabry disease interferes with the function of an enzyme which processes biomolecules known as sphingolipids, leading to these substances building up in the walls of blood vessels and other organs. It is inherited in an X-linked manner.

Fabry disease is sometimes diagnosed using a blood test that measures the activity of the affected enzyme called alpha-galactosidase, but genetic testing is also sometimes used, particularly in females.

The treatment for Fabry disease varies depending on the organs affected by the condition, and the underlying cause can be addressed by replacing the enzyme that is lacking.

The first descriptions of the condition were made simultaneously by the dermatologist Johannes Fabry[2] and the surgeon William Anderson[3] in 1898.[4]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms are typically first experienced in early childhood and can be very difficult to understand; the rarity of Fabry disease to many clinicians sometimes leads to misdiagnoses. Manifestations of the disease usually increase in number and severity as an individual ages.[5]

Pain

Full body or localized pain to the extremities (known as acroparesthesia) or gastrointestinal (GI) tract is common in patients with Fabry disease. This acroparesthesia is believed to be related to the damage of peripheral nerve fibers that transmit pain. GI tract pain is likely caused by accumulation of lipids in the small vasculature of the GI tract which obstructs blood flow and causes pain.[6]

Kidney

Kidney complications are a common and serious effect of the disease; kidney insufficiency and kidney failure may worsen throughout life. The presence of protein in the urine (which causes foamy urine) is often the first sign of kidney involvement. End-stage kidney failure in those with Fabry disease typically occurs in the third decade of life, and is a common cause of death due to the disease.

Heart

Fabry disease can affect the heart in several ways. The accumulation of sphingolipids within heart muscle cells causes abnormal thickening of the heart muscle or hypertrophy. This hypertrophy can cause the heart muscle to become abnormally stiff and unable to relax, leading to a restrictive cardiomyopathy causing breathlessness.[7][8]

Fabry disease can also affect the way in which the heart conducts electrical impulses, leading to both abnormally slow heart rhythms such as complete heart block, but also abnormally rapid heart rhythms such as ventricular tachycardia. These abnormal heart rhythms can cause blackouts, palpitations, or even sudden cardiac death.[7][8]

Sphingolipids can also build up within the heart valves, thickening the valves and affecting the way they open and close. If severe, this can cause the valves to leak (regurgitation) or to restrict the forward flow of blood (stenosis). The aortic and mitral valves are more commonly affected than the valves on the right side of the heart.[7][8]

Skin

Angiokeratomas (tiny, painless papules that can appear on any region of the body, but are predominant on the thighs, around the belly button, buttocks, lower abdomen, and groin) are common.

Anhidrosis (lack of sweating) is a common symptom, and less commonly hyperhidrosis (excessive sweating).

Additionally, patients can exhibit Raynaud's disease-like symptoms with neuropathy (in particular, burning extremity pain).

Ocular involvement may be present showing cornea verticillata (also known as vortex keratopathy), i.e. clouding of the corneas. Keratopathy may be the presenting feature in asymptomatic patients, and must be differentiated from other causes of vortex keratopathy (e.g. drug deposition in the cornea).[9] This clouding does not affect vision.[9]

Other ocular findings can include conjunctival and retinal vascular abnormalities and anterior/posterior spoke-like cataract. Visual reduction from these manifestations is uncommon.

Other manifestations

Fatigue, neuropathy (in particular, burning extremity pain, red hands and feet on and off), cerebrovascular effects leading to an increased risk of stroke - early strokes, mostly vertebro-basilar system tinnitus (ringing in the ears), vertigo, nausea, inability to gain weight, and diarrhea are other common symptoms.

Causes

A deficiency of the enzyme alpha galactosidase A (a-GAL A, encoded by GLA) due to mutation causes a glycolipid known as globotriaosylceramide (abbreviated as Gb3, GL-3, or ceramide trihexoside) to accumulate within the blood vessels, other tissues, and organs.[10] This accumulation leads to an impairment of their proper functions.

The DNA mutations which cause the disease are X-linked recessive with incomplete penetrance in heterozygous females. The condition affects hemizygous males (i.e. all males), as well as homozygous, and in many cases heterozygous females. While males typically experience severe symptoms, women can range from being asymptomatic to having severe symptoms. New research suggests many women suffer from severe symptoms ranging from early cataracts or strokes to hypertrophic left ventricular heart problems and kidney failure. This variability is thought to be due to X-inactivation patterns during embryonic development of the female.[11]

Diagnosis

Fabry disease is suspected based on the individual's clinical presentation, and can be diagnosed by an enzyme assay (usually done on leukocytes) to measure the level of alpha-galactosidase activity. An enzyme assay is not reliable for the diagnosis of disease in females due to the random nature of X-inactivation. Molecular genetic analysis of the GLA gene is the most accurate method of diagnosis in females, particularly if the mutations have already been identified in male family members. Many disease-causing mutations have been noted. Kidney biopsy may also be suggestive of Fabry disease if excessive lipid buildup is noted. Pediatricians, as well as internists, commonly misdiagnose Fabry disease.[12]

Treatment

The treatments available for Fabry disease can be divided into therapies that aim to correct the underlying problem of decreased activity of the alpha galactosidase A enzyme and thereby reduce the risk of organ damage, and therapies to improve symptoms and life expectancy once organ damage has already occurred.

Enzyme replacement therapy

Enzyme replacement therapy is designed to provide the enzyme the patient is missing as a result of a genetic malfunction. This treatment is not a cure, but can partially prevent disease progression, as well as potentially reverse some symptoms.[13]

The pharmaceutical company Shire manufactures agalsidase alpha (which differs in the structure of its oligosaccharide side chains[14]) under the brand name Replagal as a treatment for Fabry's disease,[15] and was granted marketing approval in the EU in 2001.[16] FDA approval was applied for the United States.[17] However, Shire withdrew their application for approval in the United States in 2012, citing that the agency will require additional clinical trials before approval.[18]

The first treatment for Fabry's disease to be approved by the US FDA was Fabrazyme (agalsidase beta, or Alpha-galactosidase) in 2003, licensed to the Genzyme Corporation.[19] The drug is expensive — in 2012, Fabrazyme's annual cost was about US$200,000 per patient,[20] which is unaffordable to many patients around the world without enough insurance.

Clinically the two products are generally perceived to be similar in effectiveness. Both are available in Europe and in many other parts of the world, but treatment costs remain very high.[21]

Besides these drugs, a gene therapy treatment is in clinical trials,[22][23] with the technology licensed to AvroBio.[24] Other treatments (oral chaperone therapy -Amicus-, plant-based ERT -Protalix-, substrate reduction therapy -Sanofi-Genzyme-, bio-better ERT -Codexis-, gene editing solution -Sangamo- are currently being researched.[25]

Organ-specific treatment

Pain associated with Fabry disease may be partially alleviated by ERT in some patients, but pain management regimens may also include analgesics, anticonvulsants, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, though the latter are usually best avoided in renal disease. The kidney failure seen in some of those with Fabry disease sometimes requires haemodialysis. The cardiac complications of Fabry disease include abnormal heart rhythms which may require a pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, while the restrictive cardiomyopathy often seen may require diuretics.[13]

Prognosis

Life expectancy with Fabry disease for males was 58.2 years, compared with 74.7 years in the general population, and for females 75.4 years compared with 80.0 years in the general population, according to registry data from 2001 to 2008. The most common cause of death was cardiovascular disease, and most of those had received kidney replacements.[26]

Epidemiology

Fabry disease is estimated to occur in one in 40,000 to one in 120,000 live births.[27]

History

Fabry disease was first described by the dermatologist Johannes Fabry [2] and the surgeon William Anderson [3] independently in 1898.[4] It was recognised that this was due to abnormal storage of lipids in 1952. In the 1960s the inheritance pattern was established as being X-linked, as well as the molecular defect responsible for causing the accumulation of glycolipids.[4]

Ken Hashimoto published his classic paper on his electron microscopic findings in Fabry disease in 1965.[28][29]

The first specific treatment for Fabry disease was approved in 2001.[13][16]

Society and Culture

- House ("Epic Fail", season 6 episode 2) centers on a patient with Fabry disease.

- Scrubs ("My Catalyst", season 3 episode 12) features a Fabry disease diagnosis.

- Crossing Jordan ("There's No Place Like Home", season 2 episode 1) features a patient who died suffering Fabry disease.

- The Village: Achiara's Secret[30] (Korean Drama) features daughters of a serial rapist who find each other because they share Fabry disease.

See also

References

- ↑ James, Berger & Elston 2006, p. 538

- 1 2 Fabry, Joh (December 1898). "Ein Beitrag zur Kenntniss der Purpura haemorrhagica nodularis (Purpura papulosa haemorrhagica Hebrae)". Archiv für Dermatologie und Syphilis (in German). 43 (1): 187–200. doi:10.1007/bf01986897. ISSN 0340-3696.

- 1 2 ANDERSON, WILLIAM (April 1898). "A CASE OF "ANGEIO-KERATOMA."". British Journal of Dermatology. 10 (4): 113–117. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1898.tb16317.x. ISSN 0007-0963.

- 1 2 3 Schiffmann, Raphael (2015). Fabry disease. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 132. pp. 231–248. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-62702-5.00017-2. ISBN 9780444627025. ISSN 0072-9752. PMID 26564084.

- ↑ "Fabry disease | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Retrieved 2018-04-17.

- ↑ Hoffmann, Bjoern; Beck, Michael; Sunder-Plassmann, Gere; Borsini, Walter; Ricci, Roberta; Mehta, Atul (2007). "Nature and prevalence of pain in Fabry disease and its response to enzyme replacement therapy—a retrospective analysis from the Fabry Outcome Survey". The Clinical Journal of Pain. 23 (6): 535–542. doi:10.1097/AJP.0b013e318074c986. PMID 17575495.

- 1 2 3 Putko, Brendan N.; Wen, Kevin; Thompson, Richard B.; Mullen, John; Shanks, Miriam; Yogasundaram, Haran; Sergi, Consolato; Oudit, Gavin Y. (March 2015). "Anderson-Fabry cardiomyopathy: prevalence, pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment". Heart Failure Reviews. 20 (2): 179–191. doi:10.1007/s10741-014-9452-9. ISSN 1573-7322. PMID 25030479.

- 1 2 3 Akhtar, M. M.; Elliott, P. M. (2018-06-16). "Anderson-Fabry disease in heart failure". Biophysical Reviews. 10 (4): 1107–1119. doi:10.1007/s12551-018-0432-5. ISSN 1867-2450. PMC 6082315. PMID 29909504.

- 1 2 Chew, E.; Ghosh, M.; McCulloch, C. (June 1982). "Amiodarone-induced cornea verticillata". Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology. 17 (3): 96–99. PMID 7116220.

- ↑ Karen, Julie K.; Hale, Elizabeth K.; Ma, Linglei (2005). "Angiokeratoma corporis diffusum (Fabry disease)". Dermatology Online Journal. 11 (4): 8. PMID 16403380.

- ↑ James, Berger & Elston 2006, pp.

- ↑ Marchesoni, Cintia L.; Roa, Norma; Pardal, Ana María; Neumann, Pablo; Cáceres, Guillermo; Martínez, Pablo; Kisinovsky, Isaac; Bianchi, Silvia; Tarabuso, Ana Lía; Reisin, Ricardo C. (May 2010). "Misdiagnosis in Fabry disease". The Journal of Pediatrics. 156 (5): 828–31. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.02.012. PMID 20385321.

- 1 2 3 Wanner, Christoph; Arad, Michael; Baron, Ralf; Burlina, Alessandro; Elliott, Perry M.; Feldt-Rasmussen, Ulla; Fomin, Victor V.; Germain, Dominique P.; Hughes, Derralynn A. (June 2018). "European expert consensus statement on therapeutic goals in Fabry disease". Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 124 (3): 189–203. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2018.06.004. ISSN 1096-7206. PMID 30017653.

- ↑ Fervenza, Fernando C.; Torra, Roser; Warnock, David G. (December 2008) [13 November 2008]. "Safety and efficacy of enzyme replacement therapy in the nephropathy of Fabry disease". Biologics. 2 (4): 823–843. doi:10.2147/btt.s3770. PMC 2727881. PMID 19707461.

- ↑ Keating, Gillian M. (October 2012). "Agalsidase alfa: a review of its use in the management of Fabry disease". BioDrugs. 26 (5): 335–354. doi:10.2165/11209690-000000000-00000. PMID 22946754.

- 1 2 "Shire Submits Biologics License Application (BLA) for Replagal with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)". FierceBiotech.

- ↑ "With A Life-Saving Medicine In Short Supply, Patients Want Patent Broken". 2010-08-04. Archived from the original on 14 September 2010. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- ↑ Grogan, K. (2012-03-15). "Shire withdraws Replagal in USA as FDA wants more trials". PharmaTimes. Archived from the original on 2014-08-19.

- ↑ "Fabrazyme Prescribing Information (USA)" (PDF). www.fda.gov.

- ↑ Pollack, Andrew (April 15, 2010). "Genzyme Drug Shortage Leaves Users Feeling Betrayed". New York Times.

- ↑ Waldek, S. Fabry Disease: management and outcome. Chapter 338 in Oxford Textbook of Nephrology (4th ed) 2015, eds Turner, Lameire, et al.

- ↑ Gene therapy treatment for Fabry disease patients

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Treatments for Fabry disease

- ↑ Waldek, Stephen; Patel, Manesh R.; Banikazemi, Maryam; Lemay, Roberta; Lee, Philip (November 2009). "Life expectancy and cause of death in males and females with Fabry disease: findings from the Fabry Registry". Genetics in Medicine. 11 (11): 790–796. doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181bb05bb. PMID 19745746.

- ↑ Mehta, A.; Ricci, R.; Widmer, U.; Dehout, F.; Garcia de Lorenzo, A.; Kampmann, C.; Linhart, A.; Sunder-Plassmann, G.; Ries, M.; Beck, M. (March 2004). "Fabry disease defined: baseline clinical manifestations of 366 patients in the Fabry Outcome Survey". European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 34 (3): 236–42. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2362.2004.01309.x. PMID 15025684.

- ↑ John Thorne Crissey; Lawrence C. Parish; Karl Holubar (2013). Historical Atlas of Dermatology and Dermatologists. CRC Press. p. 179. ISBN 978-1-84214-100-7.

- ↑ Mehta, Atul; Beck, Michael; Linhart, Aleš; Sunder-Plassmann, Gere; Widmer, Urs (2006), Mehta, Atul; Beck, Michael; Sunder-Plassmann, Gere, eds., "History of lysosomal storage diseases: an overview", Fabry Disease: Perspectives from 5 Years of FOS, Oxford PharmaGenesis, ISBN 978-1903539033, PMID 21290707, retrieved 10 August 2018

- ↑ "The Village: Achiara's Secret".

Sources and further reading

- James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G.; Elston, Dirk (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7216-2921-6.

- Schiffmann, Raphael; Kopp, Jeffrey B.; Austin, Howard A.; Sabnis, Sharda; Moore, David F.; Weibel, Thais; Balow, James E.; Brady, Roscoe O. (June 2001). "Enzyme replacement therapy in Fabry disease: a randomized controlled trial". JAMA. 285 (21): 2743–2749. doi:10.1001/jama.285.21.2743. PMID 11386930.

- Wilcox, William R.; Banikazemi, Maryam; Guffon, Nathalie; Waldek, Stephen; Lee, Philip; Linthorst, Gabor E.; Desnick, Robert J.; Germain, Dominique P. (July 2004). "Long-term safety and efficacy of enzyme replacement therapy for Fabry disease". American Journal of Human Genetics. 75 (1): 65–74. doi:10.1086/422366. PMC 1182009. PMID 15154115.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Fabry Disease Information Page at NINDS

- Fabry disease at NLM Genetics Home Reference

- Fabry Registry

- Stroke in young Fabry patients

- Datagenno - Fabry Disease