Elizabeth Seymour, Lady Cromwell

| Elizabeth Seymour | |

|---|---|

|

Baroness Cromwell Baroness St. John | |

| Born | c. 1518 |

| Died | 19 March 1568[1][2] |

| Buried |

St. Mary's Church, Basing, Hampshire 51°16′17″N 1°02′48″W / 51.271389°N 1.046667°W |

| Spouse(s) |

Sir Anthony Ughtred Gregory Cromwell, 1st Baron Cromwell John Paulet, 2nd Marquess of Winchester |

|

Issue

Henry Ughtred Margery Ughtred Henry Cromwell, 2nd Baron Cromwell Edward Cromwell Thomas Cromwell Catherine Cromwell Frances Cromwell | |

| Father | Sir John Seymour |

| Mother | Margery Wentworth |

Elizabeth Seymour (c. 1518 – 19 March 1568[1]) was the daughter of Sir John Seymour of Wulfhall, Wiltshire and Margery Wentworth.[3] Elizabeth and her sister Jane Seymour served in the household of Anne Boleyn, the second wife of Henry VIII.[4][5] In his quest for a male heir, the king had divorced his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, whose only surviving child was a daughter, Mary. His marriage to Anne Boleyn had also resulted in a single daughter, Elizabeth. The queen's miscarriage of a son in January 1536 sealed her fate. The king, convinced that Anne could never give him male children, increasingly infatuated with Jane Seymour, and encouraged by the queen's enemies, was determined to replace her. The Seymours rose to prominence after the king's attention turned to Jane.[6]

In May 1536, Anne Boleyn was accused of treason and adultery with Mark Smeaton, a court musician, the courtiers Henry Norris, Sir Francis Weston, William Brereton and her brother, George Boleyn, Viscount Rochford. The trials and executions of the queen and her co-accused followed swiftly,[7][8] and on 30 May 1536, eleven days after Anne's execution, Henry VIII and Jane were married.[9] Elizabeth was not included in her sister's household during her brief reign, although she would serve two of Henry VIII's later wives, Anne of Cleves[10] and Catherine Howard.[11] Jane died 24 October 1537, twelve days after giving birth to a healthy son, Edward VI.[12]

Elizabeth lived under four Tudor monarchs and was married three times. In 1531, she married Sir Anthony Ughtred, Governor of Jersey, who died in 1534. She then married Gregory Cromwell, 1st Baron Cromwell, the son of Thomas Cromwell, chief minister to Henry VIII in 1537, who died in 1551. She married her third and last husband, John Paulet, Lord St John, the son of William Paulet, 1st Marquess of Winchester in 1554.[13]

Seymour family

The Seymour family took its name from St. Maur-sur-Loire in Touraine. William de St. Maur in 1240 held the manors of Penhow and Woundy (now called Undy in Monmouthshire). William's great-grandson, Sir Roger de St. Maur, had two sons: John, whose granddaughter conveyed these manors by marriage into the family of Bowlay of Penhow, who bore the Seymour arms; and Sir Roger (c. 1308 – Bef. 1366), who married Cicely, eldest sister and heir of John de Beauchamp, 3rd Baron Beauchamp. Cicely brought to the Seymours the manor of Hache, Somerset, and her grandson, Roger Seymour, by his marriage with Maud, daughter and heir of Sir William Esturmy, acquired Wolf Hall in Wiltshire.[14] Elizabeth's father, Sir John Seymour, was a great-great-grandson of this Roger Seymour.[15]

Sir John Seymour was born in 1474.[16][17] He succeeded his father in 1492, was knighted by Henry VII for his services against the Cornish rebels at Blackheath in 1497, and was sheriff of Wiltshire in 1508. He was present at the sieges of Thérouanne and Tournay in 1513, at the two interviews between Henry VIII and Francis I in 1520 and 1532, and died on 21 December 1536.

He married Margery, the daughter of Sir Henry Wentworth of Nettlestead, Suffolk, and his wife Anne Say.[15] Anne was the daughter of Sir John Say and his wife, Elizabeth, daughter of Lawrence Cheney (or Cheyne) (c. 1396 – 1461) and Elizabeth Cokayne.[15] Margery Wentworth's grandfather, Sir Philip Wentworth, had married Mary, daughter of John Clifford, 7th Baron de Clifford, whose mother Elizabeth was daughter of Henry Percy (Hotspur) and great-great-granddaughter of Edward III.[16]

Sir John Seymour (1474 – 21 December 1536),[17][18] of Wulfhall, Savernake, Wiltshire, and his wife Margery Wentworth (c. 1478 – c. October 1550) were married 22 October 1494.[3] The couple had ten children: [3][13]

- John Seymour (died 15 July 1510)[19][20]

- Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset, Lord Protector of Edward VI (c. 1500[21]/1506[15] – 22 January 1552)[22] married firstly Catherine, daughter of Sir William Fillol,[15] and secondly Anne, daughter of Sir Edward Stanhope.[15]

- Sir Henry Seymour (1503 – 1578) married Barbara, daughter of Morgan Wolfe[23]

- Thomas Seymour, 1st Baron Seymour of Sudeley (c. 1508 – 20 March 1549) married Catherine Parr, widow of Henry VIII[24][25]

- John Seymour (died young)[26]

- Anthony Seymour (died c. 1528)[19]

- Jane Seymour, queen Consort of Henry VIII (c. 1509 – 24 October 1537)[3][6]

- Margery Seymour (died c. 1528)[19]

- Elizabeth Seymour (c. 1518[27] – 19 Mar 1568[1])

- Dorothy Seymour (c. 1519 – )[26] married firstly, Sir Clement Smith (c. 1515 – 26 August 1552) of Little Baddow, Essex[20][28] and secondly, Thomas Leventhorpe of Shingle Hall,[29] Hertfordshire.[26][30]

Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset

Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset Thomas Seymour, Baron Seymour

Thomas Seymour, Baron Seymour Jane Seymour, portrait miniature c. 1536–37, Lucas Horenbout

Jane Seymour, portrait miniature c. 1536–37, Lucas Horenbout

Of the ten children born at Wulfhall, six survived:– three sons: Edward, Henry and Thomas, and three daughters: Jane, Elizabeth and Dorothy. Edward, Thomas, Jane and Elizabeth were courtiers. Edward and Thomas were both executed during the reign of Edward VI. Henry Seymour, who did not share his brothers' ambition, lived away from court, in relative obscurity, and escaped their fate.[23]

Early life

Elizabeth Seymour was probably born at Wulfhall around 1518. Her letters to Thomas Cromwell and Henry VIII show that she was both intelligent and astute.[31][32][33] She was also skilled in needlework[34] Elizabeth played a brief but prominent role in the 1530s and 1540s, during the rise to power of her father-in-law, Thomas Cromwell, and her brother, Edward.[35] Elizabeth and her sister, Jane, served in the household of Henry VIII's second wife, Anne Boleyn, their second cousin.[36][37] She married three times and by her first two marriages had seven children. She is best known as the wife of Gregory Cromwell.

First marriage

In January 1531,[38] Elizabeth married, as his second wife,[39] Sir Anthony Ughtred, of Kexby, Yorkshire.[13] The couple had two children:

- Henry Ughtred, (c. 1533[40] – c. 1598), born at Mont Orgueil, Jersey,[41] married Elizabeth, daughter to John Paulet, 2nd Marquess of Winchester and his first wife Elizabeth Willoughby and the widow of Sir William Courtenay.[42] After his wife's death in 1576,[43] Henry remarried, however the identity of his second wife is not recorded.[42]

- Margery Ughtred, (c. 1535 –?) married William Hungate of Burnby,Yorkshire.[44]

In the same month, Henry VIII granted the couple the manors of Lepington and Kexby (Yorkshire), previously held by Cardinal Thomas Wolsey.[38] Elizabeth was well-placed at court, in the service of Anne Boleyn, to support her husband's interests.[34][37] In August 1532, when the pro-Boleyn Sir Anthony Ughtred was appointed captain and Governor of Jersey, it was almost certainly due to the influence of Anne Boleyn.[37][41] He served in person, and remained in the post until his death.[41]

Sir Anthony Ughtred died 6 October 1534 on Jersey, and was buried in the chapel of St George, in the castle of Mont Orgueil.[45] After her husband's death, Elizabeth returned to Kexby, Yorkshire where her daughter, Margery was probably born.[44] Her one-year-old son, Henry, remained on the island for a time, in the care of Helier de Carteret, Bailiff of Jersey.[40][41]

The Queen's sister

When Anne Boleyn failed to produce a male heir after almost three years of marriage, the able and ambitious Edward Seymour and his family, gained wealth and power as Jane supplanted Anne in the king's affection. In March 1536, Edward was made a gentleman of the privy chamber, and a few days later, he and his wife Anne together with his sister Jane, were lodged at the palace at Greenwich in apartments which the king could reach through a private passage.[46]

In May 1536, accused of treason, incest and plotting the king's death, Anne was imprisoned in the Tower, awaiting her trial. Jane Seymour resided with members of her family, first at the home of Sir Nicholas Carew in Surrey and then moved closer to the king, to a house at Chelsea, formerly owned by Thomas More.[47] While the king's second wife prepared for her execution, Jane was planning her wedding, "splendidly served by the King's cook and other officers" and "most richly dressed."[48] On 30 May 1536, eleven days after Anne Boleyn's execution, Henry VIII and Jane were married.[9] On 5 June, a week after his sister's marriage to the king, Edward Seymour was created Viscount Beauchamp.[15] Two days later he received a grant of numerous manors in Wiltshire, including Ambresbury, Easton Priory, Chippenham, and Maiden Bradley.[15] On 7 July he was made governor and captain of Jersey, and in August, chancellor of North Wales.[15] He had livery of his father's lands in the following year, was on 30 January granted the manor of Muchelney, Somerset, and on 22 May sworn of the privy council. In the same month he was on the commission appointed to try Lords Darcy and Hussey for their role in the pilgrimage of grace.[15] On 15 October he carried Princess Elizabeth at Edward VI's christening,[49] and 18 October was created Earl of Hertford.[15] Thomas Seymour was also made a gentleman of the privy chamber in 1536, and knighted 18 October of the same year. He was made captain of the Sweepstake in 1537.[24]

When Henry VIII sought to divorce his first wife, Catherine of Aragon and marry Anne Boleyn, Jane, who had previously served in Catherine's household, had remained loyal to her and her daughter, Mary.[4] Elizabeth and her first husband, Sir Anthony Ughtred had supported Anne Boleyn and benefited from her rise.[37][41] It is not surprising therefore, that she was not included in the new queen's household.[50] There is no evidence that Elizabeth benefited directly from her sister's royal status, before the news of a royal pregnancy became public knowledge in 1537. The impending birth of an heir to the throne would dramatically increase her value as a potential bride.

On 18 March 1537, then a young widow of reduced means, residing in York, Elizabeth had written to Thomas Cromwell, then Baron Cromwell, who had previously offered to help her, if she was ever in need.[51][52] She had hoped to "be holpen to obtain of the king's grace to be farmer of one of these abbeys if they fortune to go down ..." Cromwell, probably encouraged by Edward Seymour, proposed instead that she marry his only son and heir, Gregory.[53] By June, it appears that Cromwell's offer had been accepted. Arthur Darcy, the son of Thomas Darcy, 1st Baron Darcy de Darcy, assured her that "I would have been glad to have had you likewise, but sure it is, as I said, that some southern lord shall make you forget the North."[54]

Second marriage

which doth comfort me most in the world, that I find your lordship is contented with me, and that you will be my good lord and father the which, I trust, never to deserve other, but rather to give cause for the continuance of the same.

On 3 August 1537, Elizabeth married Gregory Cromwell at Mortlake.[57][58] Edward Seymour, then Viscount Beauchamp wrote to Cromwell on 2 September 1537, to know how he has fared since the writer's departure. Wishes Cromwell were with him, when he should have had the best sport with bow, hounds, and hawks and sends commendations to his brother-in-law and sister, adding: "and I pray God to send me by them shortly a nephew."[59]

The couple had five children:[13][60][61]

- Henry Cromwell, 2nd Baron Cromwell, (before 21 May 1538[62][63] – 16 December 1592[64]), married Mary, (died 1592),[2] the daughter of John Paulet, 2nd Marquess of Winchester and his first wife Elizabeth Willoughby.[64]

- Edward Cromwell, (1539 – ?)[61][63] died young

- Thomas Cromwell, (c. 1540 – died between February 1610 and April 1611), married 18 August 1580,[2] Katherine (died before 1 August 1616), daughter of Thomas Gardner of Coxford.[65]

- Catherine or Katherine Cromwell, (c. 1541 – ?), probably named after queen Catherine Howard, married Sir John Strode of Parnham, Dorset[13][66]

- Frances Cromwell, (c. 1544[67] – 7 February 1562), married Richard Strode of Newnham, Devon.[67]

On 12 November, three months after their wedding, Elizabeth and Gregory took part in the queen's funeral procession.[68] Jane's death on 24 October,[12] after being delivered of the king's longed-for son, naturally came as a blow to the Seymour family. It proved to be a setback to Edward Seymour's influence. He was described in the following year as "young and wise," but "of small power."[69] The death of the queen would have disastrous consequences for Thomas Cromwell.

The couple's first child, Henry was born in 1538,[63] probably at Lewes Priory in Sussex, which had recently been acquired by Thomas Cromwell,[70] and where they had set up house.[71] Another son, Edward, followed in 1539,[63] who may have been born, either at Leeds Castle in Kent,[72] or in London.[73]

Gregory Cromwell appears to have been devoted to his wife and their children. In December 1539, while in Calais waiting to welcome Henry VIII's new bride, Anne of Cleves, he wrote to his wife at Leeds Castle,[72] addressing her as his "loving bedfellow", describing the arrival of Anne of Cleves, and requesting news "as well of yourself as also my little boys, of whose increase and towardness be you assured I am not a little desirous to be advertised."[63] In January 1540, Elizabeth was appointed to the household of the new Queen, Anne of Cleves.[10]

Thomas Cromwell was created Earl of Essex on 17 April,[74] and his son, Gregory assumed the courtesy title of Lord Cromwell[75] In May, Lady Cromwell watched her husband compete in the May Day jousts at the Palace of Westminster and afterwards feasted with the queen and her ladies.[76][77] Anne of Cleves would not remain as queen for long, however, as the mercurial Henry VIII wanted a divorce.

Thomas Cromwell was at the height of his ascendancy, however his political enemies were gaining ground and his time in power would soon come to an end. He was arrested at a council meeting at 3.00 p.m. on the afternoon of 10 June 1540, accused of treason and heresy, taken to the Tower and his possessions seized.[78][79][80][81] He was condemned without a trial and his sentence was later confirmed by an act of attainder.[82][83] There are no surviving records of Gregory and Elizabeth's whereabouts at this time.

Thomas Cromwell wrote a desperate letter from the tower to the king to plead his innocence and appealed to him to be merciful to his son and the rest of his family.

Sir, upon [my kne]es I most humbly beseech your most gracious Majesty [to be goo]d and gracious lord to my poor son, the good and virtu[ous lady his] wife, and their poor children [84][85]

In July, Elizabeth also wrote to Henry VIII, to assure him of her loyalty and that of her husband:

After the bounden duty of my most humble submission unto your excellent majesty, whereas it hath pleased the same, of your mere mercy and infinite goodness, notwithstanding the heinous trespasses and most grievous offences of my father-in-law, yet so graciously to extend your benign pity towards my poor husband and me, as the extreme indigence and poverty wherewith my said father-in-law's most detestable offences hath oppressed us, is thereby right much holpen and relieved, like as I have of long time been right desirous presently as well to render most humble thanks, as also to desire continuance of the same your highness' most benign goodness. So, considering your grace's most high and weighty affairs at this present, fear of molesting or being troublesome unto your highness hath disuaded me as yet otherwise to sue unto your grace than alonely by these my most humble letters, until your grace's said affairs shall be partly overpast. Most humbly beseeching your majesty in the mean season mercifully to accept this my most obedient suit, and to extend your accustomed pity and gracious goodness towards my said poor husband and me, who never hath, nor, God willing, never shall offend your majesty, but continually pray for the prosperous estate of the same long time to remain and continue."[86]

This undated letter is placed at the end of July 1540 in Letters and Papers of the Reign of Henry VIII.[87]It was probably written while Thomas Cromwell was imprisoned in the Tower, as Elizabeth refers to her father-in-law, and not her late father-in-law. Moreover, it was customary at that time to write "may his soul God pardon" or something similar when referring to someone who had recently died, which she did not do.[88] The letter was almost certainly written on the advice of her brother, Edward.

Thomas Cromwell was beheaded on Tower Hill on 28 July 1540,[78][89][90] the same day as the king's marriage to Catherine Howard. He was buried in an unmarked grave in the Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula in the Tower. It is unknown if Gregory and his family were present at his execution or burial.[91]

Gregory and Elizabeth were not implicated, although it would be almost six months before their desperate situation was to be resolved. They had been dependants of Thomas Cromwell, with no home and little income of their own, and would have had to rely on the generosity of family and friends. The king was inclined to be generous and Elizabeth was included in the future queen Catherine Howard's household as one of her attendant ladies.[92]

On 18 December 1540, less than five months after his father's execution, Gregory Cromwell was created Baron Cromwell of Oakham in the County of Rutland, by letters patent, and summoned to Parliament as a peer of the realm.[93][94] This title was a new creation,[95] rather than a restoration of his father's forfeited barony.[96] The following February he received a royal grant of lands that had been owned by his late father.[97]

Following the death of Henry VIII in 1547, Thomas Seymour, Baron Seymour of Sudeley secretly married the late king's widow, Catherine Parr, who died a few days after giving birth to her only child Mary Seymour, in September 1548.[98]

At the coronation of King Edward VI, on 20 February 1547, Elizabeth's husband and her brother, Henry were invested as Knights of the Order of the Bath.[93][94][99] Her brother, Thomas was found guilty of treason and executed 20 March 1549.[24]

Elizabeth became a widow again upon the death of Gregory Cromwell from sweating sickness in 1551.[94] He died at Launde Abbey 4 July 1551 and was buried three days later in the chapel at Launde.[64] In London, Henry Machyn recorded the events in his diary:

And died my Lord Cromwell in Leicestershire and was buried with a standard, a banner of arms, and coat, helmet, sword, target, and escutcheons and herald.[100]

Gregory lies buried under a magnificent monument in the chapel at Launde. The initials "E C" can be seen in the intricate entablature beneath the pediment.[101]

Edward, Duke of Somerset, who had always been a constant source of support to his sister, Elizabeth, went to the block 22 January 1552 and his wife, remained in the Tower.[15] Since he had been found guilty of the lesser charge of felony, and not for treason, his lands and dignities were not thereby affected, however an act of parliament was passed on 12 April 1552 declaring them forfeited and confirming his attainder.[102] In May, his youngest four daughters were placed in Elizabeth's care.[103] She was granted 400 marks for the provision and education of each of her nieces per year, as well as the lease of her minor son's house of Launde Abbey, by way of an inducement. However, by October, the arrangement was placing the widow under a considerable strain.[103][104] On 25 October 1552, she wrote to her friend, Sir William Cecil, of the Privy Council, requesting to be relieved of her troublesome nieces, who did not take her advice "in such good part as my good meaning was, nor according to my expectation in them".[104] Her husband's family were all dead, her own surviving family did not live nearby, and she no longer had the support of her husband or her brother, Edward. She reminded Cecil that she had no near relations who could give her advice.[104] Her pleas fell on deaf ears and her nieces would remain with her until their mother, Anne, Duchess of Somerset, was released from the Tower by Mary I in August 1553.[105]

Third marriage

Between 10 March and 24 April 1554, Elizabeth married, as his second wife, John Paulet, Baron St John, who outlived her.[106] There were no children by this marriage. Elizabeth's two eldest sons married John Paulet's daughters. Henry Ughtred married the widowed Elizabeth after 1557[107] and Henry Cromwell married Mary sometime before 1560.[64] Details of her later life remain obscure, however she and her husband appear in the records from time to time in matters relating to her son, Henry Cromwell's minority and suits for the continuation of royal grants at the commencement of each new reign.[108]

Death

Elizabeth died 19 March 1568, and was buried 5 April[1][2] in St. Mary's Church, Basing, Hampshire.[64][109] John Paulet married, before May 1571, Winifred Brydges, daughter of Sir John Brydges (c. 1470 – 1530).[110][111] He succeeded his father as Marquess of Winchester in 1572.[111]

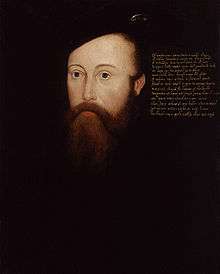

Portrait

_-_Portrait_of_a_lady%2C_probably_of_the_Cromwell_Family_formerly_known_as_Catherine_Howard_-_WGA11565.jpg)

In 1909 Sir Lionel Cust identified a portrait by Hans Holbein the Younger as a likeness of Catherine Howard.[112] Inscribed ETATIS SVAE 21, indicating that the sitter was in her 21st year, the portrait has long been associated with Henry VIII's young queen, however the identification of the portrait as Catherine Howard has been discounted.[27][112] Historians Antonia Fraser and Derek Wilson believe that the portrait is far more likely to depict Elizabeth Seymour.[113][114]

Antonia Fraser has argued that the sitter is Jane Seymour's sister, Elizabeth, the widow of Sir Anthony Ughtred, on the grounds that the lady bears a resemblance to Jane, especially around the nose and chin, and wears widow's black. Black clothing, however, was expensive, and did not necessarily signify mourning: it was an indication of wealth and status. Derek Wilson observed that "In August 1537 Cromwell succeeded in marrying his son, Gregory, to Elizabeth Seymour", the queen's younger sister. He was therefore related by marriage to the king, "an event worth recording for posterity, by a portrait of his daughter-in-law."[113] Herbert Norris notes that the sitter is wearing a sleeve which follows a style set by Anne of Cleves,[115] which would date the portrait to after 6 January 1540, when Anne's marriage to Henry VIII took place.[116]

The portrait shown on this page, attributed to Hans Holbein, dated circa 1535–1540, is exhibited at the Toledo Museum of Art as Portrait of a Lady, Probably a Member of the Cromwell Family (1926.57).[112] Another version of the portrait, now located at Hever Castle, dating from the 16th century, is exhibited as Queen Catherine Howard.[112] The National Portrait Gallery exhibits a similar painting, Unknown Woman, Formerly Known as Catherine Howard (NPG 1119),[117] which has been dated to the late 17th century. The National Portrait Gallery remains undecided about the sitter's identity.

Lineage

| Ancestors of Elizabeth Seymour, Lady Cromwell | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mont Orgueil. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lewes Priory. |

- 1 2 3 4 College of Arms 2012, p. 63.

- 1 2 3 4 Carthew 1878, p. 522.

- 1 2 3 4 Norton 2009, p. 11.

- 1 2 Beer 2004.

- ↑ Syvret 1832, pp. 59–61.

- 1 2 Wagner & Schmid 2012, p. 1000.

- ↑ Lipscomb 2013, pp. 18–24.

- ↑ The imperial ambassador, Eustace Chapuys reported to Charles V that the queen and those accused with her, "were condemned upon presumption and certain indications, without valid proof or confession."Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, 10, 908

- 1 2 Starkey 2004, p. 591.

- 1 2 Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, 15, 21.

- ↑ Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, 16, 1489

Under the heading "Rewards given on Saturday, New Year's Day at Hampton Court, anno xxxii", appearing with other ladies of the royal household, Lady Cromwell is granted 13s. 4d. - 1 2 Starkey 2004, pp. 607–608.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Richardson, Magna Carta Ancestry III 2011, p. 111.

- ↑ Roskell & Knightly 1993.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Pollard 1897, pp. 299–310.

- 1 2 Seymour 1972, p. 18.

- 1 2 Aubrey 1862, p. 375–376:John Seymour's monument gives his age as 60 which points to a birth year of 1476. "This Knight departed this Lyfe at LX years of age, the XXI day of December, Anno 1536 ..."

- ↑ Seymour 1972, pp. 18, 52.

- 1 2 3 Norton 2009, p. 13.

- 1 2 Aubrey 1862, p. 377.

- ↑ Beer 2009.

- ↑ Pole 2008, p. 481.

- 1 2 Hawkyard 1982b.

- 1 2 3 Hawkyard 1982c.

- ↑ Seymour 1972, p. 65.

- 1 2 3 Burke III 1836, p. 201.

- 1 2 Strong 1967, pp. 278–281: "The portrait should by rights depict a lady of the Cromwell family aged 21 c.1535–40..."

- ↑ Machyn 1848, p. 24, 326.

- ↑ Shingle Hall is also listed as Shingey, Shingley and Shinglehall in various sources.

- ↑ Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry III 2011, p. 82.

- ↑ Wood II 1846, pp. 353–354

- ↑ Wood II 1846, pp. 355–356

- ↑ Wood III 1846, pp. 159–160

- 1 2 Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, 5, 686: Elizabeth presented the king with "A fine shirt with a high collar" as a new year's gift in 1532.

- ↑ Loades 2013, pp. 96–97.

- ↑ Norton 2009, p. 9.

- 1 2 3 4 Syvret 1832, pp. 59–60.

- 1 2 Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, 5, 80(14).

- ↑ Collins, Yorkshire Fines: 1511-15 1887, pp. 24–30 "Anthony Ughtred, kt., and Alianora his wife" are listed under "1513–14—Hilary Term, 5 Henry VIII".

- 1 2 Syvret 1832, pp. 60–61.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Thornton 2012, p. 71.

- 1 2 Fuidge 1981.

- ↑ Cokayne IV 1916, p. 332.

- 1 2 Flower 1881, p. 166.

- ↑ MacMahon 2004.

- ↑ Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, 10, 601.

- ↑ Russell 2010.

- ↑ Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, 10, 908:The imperial ambassador, Chapuys in formed Charles V: "The day before the putain's condemnation he sent for Mrs. Semel by the Grand Esquire and some others, and made her come within a mile of his lodging, where she is splendidly served by the King's cook and other officers. She is most richly dressed. One of her relations, who dined with her on the day of the said condemnation, told me that the King sent that morning to tell her that he would send her news at 3 o'clock of the condemnation of the putain, which he did by Mr. Briant, whom he sent in all haste. To judge by appearances, there is no doubt that he will take the said Semel to wife; and some think the agreements and promises are already made."

- ↑ Wriothesley 1875, p. 68.

- ↑ Norton 2009, p. 135.

- ↑ Norton 2009, pp. 135–136.

- ↑ Wood II 1846, pp. 353–354.

- ↑ Loades 2013, pp. 95–97.

- ↑ Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, 12(2), 97.

- ↑ Wood II 1846, pp. 355–356.

- ↑ Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, 12(2), 881.

- ↑ Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, 14(2), 782.

- ↑ Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, 12(2), 423.

- ↑ Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, 12(2), 629.

- ↑ Cokayne III 1913, pp. 557–558.

- 1 2 Noble 1784, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ CPR Elizabeth I, 1: 1558-1560, p. 73 Henry was 21 c. 21 May 1559.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wood II 1846, pp. 357–358: Gregory and Elizabeth were married by 3 August 1537 and had two "little boys" by December 1539. Henry was born in 1538 and Edward in 1539.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cokayne III 1913, p. 558.

- ↑ N.M.S. 1981.

- ↑ Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry I 2011, pp. 604.

- 1 2 Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry I 2011, pp. 605, 628.

- ↑ Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, 12(2), 1060.

- ↑ Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, 13(2), 732.

- ↑ Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, 13(1), 384(74).

- ↑ Ellis, third series III 1846, pp. 192–194:The Priory House at Lewes, in which they resided, afterwards named "The Lord's Place", was destroyed by fire in the seventeenth century. It lay a short distance to the south-east of the present Southover Church.

- 1 2 Thomas Cromwell was the constable of Leeds Castle from January 1539 to 1540 Bindoff 1982

- ↑ Gregory Cromwell was elected to the House of Commons as one of the knights of the shire for Kent, and summoned to Parliament in April 1539. Hawkyard 1982a

- ↑ Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, 15, 611(37).

- ↑ Holinshed 1808, p. 815, After his father's creation as Earl of Essex in April, Gregory assumed the courtesy title of Lord Cromwell.

- ↑ Wriothesley 1875, pp. 116–117.

- ↑ Holinshed 1808, pp. 815–816.

- 1 2 Foxe V 1838, p. 398.

- ↑ Holinshed 1808, p. 816.

- ↑ Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, 15, 804.

- ↑ Journal of the House of Lords 1, 10 June 1540.

- ↑ Bindoff 1982.

- ↑ Schofield 2011, p. 396.

- ↑ Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, 15, 824.

- ↑ Ellis, second series II 1827, pp. 160–161.

- ↑ Wood III 1846, p. 159.

- ↑ Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, 15, 940.

- ↑ See Wood II 1846, pp. 353–354, The widow, Lady Ughtred's first letter to Thomas Cromwell, Wood II 1846, pp. 209–212, Lady Berkeley's letter to Thomas Cromwell after the death of her husband, Thomas Berkeley, 6th Baron Berkeley, and Ellis II 1825, pp. 67–68, Lady Rochford's letter to Thomas Cromwell after the execution of her husband George Boleyn, Viscount Rochford.

- ↑ Hall 1809, p. 839.

- ↑ Holinshed 1808, p. 817.

- ↑ Roper 2003, p. 57, Sir Thomas More's family had been given the king's permission to do so. "And I beseech you, good Mr. Pope, to be a mean unto his Highness, that my daughter Margaret may be present at my burial."

"The King is well contended already" (quoth Mr. Pope) "that your wife, children, and other friends shall have free liberty to be present thereat." - ↑ Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, 16, 1489

Under the heading 'Rewards given on Saturday, New Year's Day at Hampton Court, anno xxxii', appearing with other ladies of the royal household, Lady Crumwell is granted 13s. 4d. - 1 2 Cokayne III 1913, pp. 557–559.

- 1 2 3 Hawkyard 1982a.

- ↑ Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, 16, 379(34).

- ↑ Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, 11, 202(14).

- ↑ Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, 16, 580(49).

- ↑ Fraser 2002, pp. 487, 497–498.

- ↑ Strype II(I) 1822, p. 36.

- ↑ Machyn 1848, p. 7, 317.

- ↑ Pevsner 2003, pp. 198, 288, plate 28 The monument to Gregory Cromwell, which is to the left of the altar, is said to be one of the finest examples of early English Renaissance sculpture in the country, very "grand and restrained"

- ↑ Journal of the House of Lords 1, 12 April 1552.

- 1 2 Acts of the Privy Council IV: 1552–1554, pp. 33, 43, 62.

- 1 2 3 Wood III 1846, pp. 260–262.

- ↑ Seymour 1972, p. 365.

- ↑ Faris 1999, p. 269.

- ↑ Cokayne IV 1916, p. 332–333.

- ↑ CPR Elizabeth I, 1: 1558-1560, p. 83.

- ↑ Richardson, Magna Carta Ancestry III 2011, p. 111–112.

- ↑ Cokayne IV 1916, pp. 11, 422.

- 1 2 Cokayne VIII 1898, p. 173.

- 1 2 3 4 Russell 2017, pp. 385–387.

- 1 2 Wilson 2006, p. 215.

- ↑ Fraser 2002, p. 386.

- ↑ Norris 1998, p. 281.

- ↑ Wagner & Schmid 2012, p. 38 Anne of Cleves was queen consort from 6 January – 9 July 1540. Until 1752, the year commenced on Lady Day, 25 March.

- ↑ "Portrait NPG 1119; Unknown woman, formerly known as Catherine Howard". Npg.org.uk. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ↑ Also known as Sir Robert Coker of Lydeard St Lawrence.

- Attribution

Bibliography

- Aubrey, John; Jackson, John Edward (1862). Wiltshire: The Topographical Collections of John Aubrey, F.R.S., A.D. 1659–70, With Illustrations. Corrected and enlarged by John Edward Jackson. London, UK: Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society.

- Beer, Barrett L. (2004). "Jane [née Jane Seymour] (1508/09–1537)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/14647. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Beer, Barrett L. (January 2009) [First published 2004]. "Seymour, Edward, duke of Somerset (c.1500–1552)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/25159. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Bernard, G.W. (May 2011) [2004]. "Seymour, Thomas, Baron Seymour of Sudeley (b. in or before 1509-d. 1549)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/25181. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Bindoff, S.T. (1982). Bindoff, S.T., ed. Cromwell, Thomas (by 1485–1540), of London. Members. The History of Parliament: The House of Commons 1509–1558. 1: Appendices, constituencies, members A–C. London, UK: Secker & Warburg. ISBN 0436042827.

- Burke, John (1836). A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Commoners of Great Britain and Ireland, Enjoying Territorial Possessions or High Official Rank; But Invested With Heritable Honours. III. London, UK: Published for Henry Colburn by R. Bentley.

- "Calendar of State Papers, Spain". British-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- "Calendar of the Patent Rolls Preserved in the Public Record Office: Elizabeth [I]". London, UK: H.M.S.O. 1939. Retrieved 19 April 2014. at HathiTrust

- Carthew, G.A. (1878). The Hundred of Launditch and Deanery of Brisley; in the County of Norfolk; Evidences and Topographical Notes from public records, Heralds' Visitations, Wills, Court Rolls, Old Charters, Parish Registers, Town books, and Other Private Sources; Digested and Arranged as Materials for Parochial, Manorial, and Family History. II. Collected by G.A. Carthew. Norwich, UK: Printed by Miller and Leavins.

- Cokayne, G.E. (1913). Gibbs, Vicary; Doubleday, H. Arthur, eds. The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom, Extant, Extinct or Dormant. III. London, UK: St. Catherine Press.

- Cokayne, G.E. (2000). Gibbs, Vicary; Doubleday, H.A.; White, Geoffrey H.; Warrand, Duncan; Lord Howard de Walden, eds. The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom, Extant, Extinct or Dormant. III (new ed.). Gloucester, UK: Alan Sutton Publishing. pp. 555, 557–558.

- Cokayne, G.E. (1916). Gibbs, Vicary, ed. The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom, Extant, Extinct or Dormant. IV. London, UK: St. Catherine Press.

- Cokayne, G.E. (1898). Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom, Extant, Extinct or Dormant. VIII. Exeter: William Pollard.

- Colby, Frederic Thomas, ed. (1872). The Visitation of the County of Devon in the Year 1620. Publications of the Harleian Society. VI. Edited by Frederic Thomas Colby. London, UK: Printed by Taylor and Co.

- College of Arms (1829) [S. and R. Bentley, London, 1829]. Catalogue of the Arundel Manuscripts in the Library of the College of Arms. William Henry Black. With a preface signed C.G.Y., i.e. Sir Charles George Young. Rarebooksclub.com (published 20 May 2012). ISBN 9781236284259.

- Collins, Francis, ed. (1887). "Yorkshire Fines: 1511–15". Feet of Fines of the Tudor period [Yorks]: part 1: 1486-1571. British-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- "Cromwell, Barons (E, 1540 - 1687)". Cracroft's Peerage. Cracroftspeerage.co.uk. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- Dasent, John Roche, ed. (1892) [First published HMSO:1892]. Acts of the Privy Council of England. New Series. IV: 1552–1554. British-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- Davids, R.L. (1982). Bindoff, S.T., ed. "Seymour, Sir John (1473/74–1536), of Wolf Hall, Wilts". Members. The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1509–1558. Historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Ellis, Henry (1825). Original Letters Illustrative of English History. Second Series. II (2nd ed.). London, UK: Harding and Lepard.

- Ellis, Henry (1827). Original Letters Illustrative of English History. Second Series. II. London, UK: Harding and Lepard.

- Ellis, Henry (1846). Original Letters Illustrative of English History. third series. III. London, UK: RichardBentley.

- Faris, David (1999). Plantagenet Ancestry of Seventeenth-Century Colonists: The Descent from the Later Plantagenet Kings of England, Henry III, Edward I, Edward II, and Edward III, of Emigrants from England and Wales to the North American Colonies Before 1701 (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: New England Historic Genealogical Society. ISBN 0880821078.

- Flower, William (1881). Norcliffe, Charles Best, ed. The Visitation of Yorkshire in the Years 1563 and 1564, Made by William Flower, Esquire, Norroy king of Arms. Publications of the Harleian Society. XVI. Edited by Charles Best Norcliffe. London, UK: Mitchell and Hughes, Printers.

- Foxe, John (1838). Cattley, S.R., ed. The Acts and Monuments of John Foxe. V.

- Fraser, Antonia (2002). The Six Wives of Henry VIII. London, UK: Phoenix. ISBN 978-1-8421-2633-2.

- Fuidge, N.M. (1981). Hasler, P.W., ed. Ughtred, Henry (by 1534–aft. October 1598), of Southampton and Ireland. Members. The History of Parliament: The House of Commons 1558–1603. Historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- Hall, Edward (1809). Hall's chronicle; Containing the History of England, During the Reign of Henry the Fourth, and the Succeeding Monarchs, to the End of the Reign of Henry the Eighth, in Which are Particularly Described the Manners and Customs of Those Periods. London, UK: J. Johnson; F. C. and J. Rivington; T. Payne; Wilkie and Robinson; Longman, Hurst, Rees and Orme; Cadell and Davies; and J. Mawman.

- Hawkyard, A.D.K. (1982). Bindoff, S.T., ed. Cromwell, Gregory (by 1516–51), of Lewes, Suss.; Leeds Castle, Kent and Launde, Leics. Members. The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1509–1558. Historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- Hawkyard, A.D.K. (1982). Bindoff, S.T., ed. Seymour, Sir Henry (by 1503–78), of Marwell, Hants. Members. The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1509–1558. Historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Hawkyard, A.D.K. (1982). Bindoff, S.T., ed. Seymour, Sir Thomas II (by 1509–49), of Bromham, Wilts., Seymour Place, London and Sudeley Castle, Glos. The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1509–1558. Historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Holinshed, Raphael (1808). Holinshed's Chronicles of England, Scotland and Ireland. 3: England. London, UK: J. Johnson [et al].

- "Journal of the House of Lords". British-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- Leithead, Howard (2008) [2004]. "Cromwell, Thomas, Earl of Essex". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6769. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII". British-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- Lipscomb, Suzannah (April 2013). "Why Did Anne Boleyn Have to Die". BBC History Magazine. 14 (4): 18–24.

- Loades, David (2013). Jane Seymour: Henry VIII's Favourite Wife (hardback). Stroud, UK: Amberley. ISBN 9781445611570.

- Machyn, Henry (1848). Nichols, John Gough, ed. The Diary of Henry Machyn, Citizen and Merchant–Taylor of London, from A. D. 1550 to A. D. 1563. [Camden Society. Publications]. XLII. Edited by John Gough Nichols. London, UK: Camden Society by J.B. Nichols and Son.

- MacMahon, Luke (2004). "Ughtred, Sir Anthony (d. 1534)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/27979. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- N.M.S. (1981). Hasler, P.W., ed. "Cromwell, Thomas (c.1540–c.1611), of King's Lynn, Norf". The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1509–1558. Historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- Nichols, John Gough, ed. (1846). Chronicle of Calais, in the Reigns of Henry VII and Henry VIII to the Year 1540. Camden Society. Publications. 35. London, UK: Camden Society by J. B. Nichols and Son.

- Noble, Mark (1784). Memoirs of Several Persons and Families Who, by Females are Allied to, or Descended from the Protectorate–House of Cromwell. Birmingham, UK: Pearson and Rollason.

- Norris, Herbert (1998). Tudor Costume and Fashion. With a new introduction written by Richard Martin (new ed.). New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0486298450.

- Norton, Elizabeth (2009). Jane Seymour: Henry VIII's True Love (hardback). Chalford, UK: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 9781848681026.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Williamson, Elizabeth; Brandwood, Geoffrey K. (2003). The Buildings of England: Leicestershire and Rutland (hardback) (2nd ed.). New Haven; London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09618-6.

- Pole, Reginald; Mayer, Thomas F.; Walters, Courtney B. (2008). A Biographical Companion: The British Isles (hardback). The Correspondence of Reginald Pole. 4. Thomas F. Mayer and Courtney B. Walters. St Andrews Studies in Reformation History. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 9780754603290.

- Pollard, Albert Frederick (1897). "Seymour, Edward". In Lee, Sidney. Dictionary of National Biography. 51. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 299–310.

- Richardson, Douglas (2011). Everingham, Kimball G., ed. Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families. III (2nd ed.). CreateSpace. ISBN 1461045207.

- Richardson, Douglas (2011). Everingham, Kimball G., ed. Plantagenet Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families. III (2nd ed.). CreateSpace. ISBN 1461045134.

- Roper, William (2003). Wegemer, Gerard B.; Smith, Stephen W., eds. The Life of Sir Thomas More, c. 1556 (PDF). Center for Thomas More Studies.

- Roskell, J.S.; Knightly, Charles (1993). Roskell, J.S.; Clark, C. Rawcliffe, eds. "Sturmy (Esturmy), Sir William (c.1356-1427), of Wolf Hall in Great Bedwyn, Wilts. and Elvetham, Hants". Members. The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1386–1421. Historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- Russell, Gareth (14 May 2010). "14 May 1536: Mistress Seymour's New Lodgings". Confessions of a Ci-Devant. Garethrussellcidevant.blogspot.com.au. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- Russell, Gareth (2017). Young & Damned & Fair: the Life of Catherine Howard. London: William Collins. ISBN 9780008128296.

- Schofield, John (2011). The Rise & Fall of Thomas Cromwell: Henry VIII's Most Faithful Servant. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-5866-3.

- Seymour, William (1972). Ordeal by Ambition: An English Family in the Shadow of the Tudors. London, UK: Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 028397866X.

- Starkey, David (2004). Six Wives: The queens of Henry VIII. London, UK: Vintage. ISBN 9780099437246.

- Strong, Roy (May 1967). "Holbein in England – I and II". The Burlington Magazine. 109 (770): 276–281. JSTOR 875299.

- Strype, John (1822). Ecclesiastical Memorials. II. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

- Syvret, George S.; Carteret, Samuel de (1832). Chroniques des Iles de Jersey, Guernesey, Auregny et Serk (in French). Auquel on a ajouté un Abrégé Historique des dites Iles par Samuel de Carteret. Guernesey: de l'imprimerie de Thomas James Mauger.

- Thornton, Tim (2012). The Channel Islands, 1370–1640: Between England and Normandy. Woodbridge, UK: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-711-4.

- Wagner, John A.; Schmid, Susan Walters (2012). Encyclopedia of Tudor England (hardback). 3. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598842982.

- Wilson, Derek (2006). Hans Holbein: Portrait of an Unknown Man (revised ed.). London, UK: Random House. ISBN 9781844139187.

- Wood, Mary Anne Everett, ed. (1846). Letters of Royal and Illustrious Ladies of Great Britain, from the Commencement of the Twelfth Century to the Close of the Reign of Queen Mary. II. London, UK: Henry Colburn.

- Wood, Mary Anne Everett, ed. (1846). Letters of Royal and Illustrious Ladies of Great Britain, from the Commencement of the Twelfth Century to the Close of the Reign of Queen Mary. III. London, UK: Henry Colburn.

- Wriothesley, Charles (1875). Hamilton, William Douglas, ed. A Chronicle Of England During The Reigns Of The Tudors: From A.D. 1485 To 1559 I. Camden Society. New Series. XI. London, UK: Camden Society.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Leeds Castle. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Launde Abbey. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to St Mary's Parish Church, Old Basing. |

- Elizabeth Seymour A biography

- Elizabeth Seymour, Lady Cromwell at Find a Grave

- St Mary's Church, Basing Paulet monuments

- Letter from Gregory Cromwell to his wife

- Elizabeth, Lady Ughtred's letters to Thomas Cromwell

- Elizabeth, Lady Cromwell's letter to Henry VIII

- Kathy Lynn Emerson, Lists of Women at the Tudor Court

- Unknown Woman, Formerly Known as Catherine Howard at the National Portrait Gallery, London