Éliphas Lévi

| Éliphas Lévi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Alphonse Louis Constant 8 February 1810 Paris, First French Empire |

| Died |

31 May 1875 (aged 65) Paris, Third French Republic |

| Part of a series on |

| Hermeticism |

|---|

|

| Mythology |

| Hermetica |

|

"Three Parts of the Wisdom of the Whole Universe" |

| Movements |

| Orders |

| Topics |

| People |

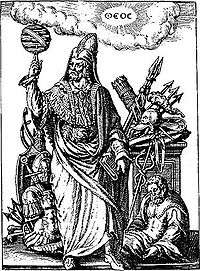

Éliphas Lévi Zahed, born Alphonse Louis Constant (February 8, 1810 – May 31, 1875), was a French occult author and ceremonial magician.[1]

"Éliphas Lévi", the name under which he published his books, was his attempt to translate or transliterate his given names "Alphonse Louis" into the Hebrew language.

Life and work until 1848

Constant was the son of a shoemaker in Paris. In 1830 he entered the seminary of Saint Sulpice to study to enter the Roman Catholic priesthood, but he fell in love and left in 1836 without being ordained. He spent the following years among his socialist and Romantic friends, including Henri-François-Alphonse Esquiros and so-called petits romantiques such as Gérard de Nerval and Théophile Gautier. During this time he turned to a radical socialism that was decisively inspired by the writings of Félicité de Lamennais, the former leader of the influential neo-Catholic movement who had recently broken with Rome and propagated a Christian socialism. When Constant published his first radical writing, La Bible de la liberté (1841, The Bible of Liberty), he was sentenced to an eight-month prison term and a high fine. Contemporaries saw in him the most notorious "disciple" of Lamennais, although the two men do not seem to have established a personal contact. In the following years, Constant would describe his ideology as communisme néo-catholique and publish a number of socialist books and pamphlets. Like many socialists, he propagated socialism as "true Christianity" and denounced the Churches as corruptors of the teachings of Christ.

Important friends at that time include, next to Esquiros, the feminist Flora Tristan, the excentric socialist mystic Simon Ganneau, and the socialist Charley Fauvety. In the course of the 1840s, Constant developed close ties to the Fourierist movement, publishing in Fourierist publications and praising Fourierism as the "true Christianity". Several of his books were published by the Fourierist Librairie phalanstérienne. He also turned to the writings of the Catholic traditionalist Joseph de Maistre, whose writings were highly popular in socialist circles. An especially radical pamphlet, La voix de la famine (1846, The Voice of Famine), earned Constant another prison sentence that was significantly shortened at the request of his pregnant wife, Marie-Noémi Cadiot.[2]

In his Testament de la liberté (1848), Constant reacted to the atmosphere that would produce the February Revolution. In 1848, he was the leader of an especially notorious Montagnard club known for its radicalism. Although it has been claimed that the Testament marked the end of Constant's socialist ambitions,[3] it has been argued that its content is in fact highly euphoric, announcing the end of the people's martyrdom and the "resurrection" of Liberty: the perfect universal, socialist order.[4] Like many other socialists, the course of events, especially the massacres of the June Uprising in 1849, left him devastated and disillusioned. As his friend Esquiros recounted, their belief in the peaceful realization of a harmonious universal had been shattered.[5]

Life and work after 1848

In December 1851, Napoleon III organized a coup that would end the Second Republic and give rise to the Second Empire. Similar to many other socialists at the time, Constant saw the emperor as the defender of the people and the restorer of public order. In the Moniteur parisien of 1852, Constant praised the new government's actions as "veritably socialist," but he soon became disillusioned with the rigid dictatorship and was eventually imprisoned in 1855 for publishing a polemical chanson against the Emperor. What had changed, however, was Constant's attitude towards "the people." As early as in La Fête-Dieu and Le livre des larmes from 1845, he had been skeptical of the uneducated people's ability to emancipate themselves. Similar to the Saint-Simonians, he had adopted the theocratical ideas of Joseph de Maistre in order to call for the establishment of a "spiritual authority" led by an élite class of priests. After the disaster of 1849, he was completely convinced that the "masses" were not able to establish a harmonious order and needed instruction (a concept similar to other socialist doctrines such as the "revolution from above", the Avantgarde, or the Partei neuen Typs.[6]

Constant's activities reflect the socialist struggle to come to terms both with the failure of 1848 and the tough repressions by the new government. He participated on the socialist Revue philosophique et religieuse, founded by his old friend Fauvety, wherein he propagated his "Kabbalistic" ideas, for the first time in public, in 1855-1856 (notably using his civil name). The debates in the Revue do not only show the tensions between the old "Romantic Socialism" of the Saint-Simonians and Fourierists, they also demonstrate how natural it was for a socialist writer to discuss topics like magic, the Kabbalah, or the occult sciences in a socialist journal.[7]

It has been shown that Constant developed his ideas about magic in a specific milieu that was marked by the confluence of socialist and magnetistic ideas.[8] Influential authors included Henri Delaage (1825–1882) and Jean du Potet de Sennevoy, who were, to different extents, propagating magnetistic, magical, and kabbalistic ideas as the foundation of a superior form of socialism. Constant used a system of magnetism and dream magic to critique what he saw as the excesses of philosophical materialism.[9]

Lévi began to write Histoire de la magie in 1860. The following year, in 1861, he published a sequel to Dogme et rituel, La clef des grands mystères ("The Key to the Great Mysteries"). In 1861 Lévi revisited London. Further magical works by Lévi include Fables et symboles ("Stories and Images"), 1862, Le sorcier de Meudon ("The Wizard of Meudon", an extended edition of two novels originally published in 1847) 1861, and La science des esprits ("The Science of Spirits"), 1865. In 1868, he wrote Le grand arcane, ou l'occultisme Dévoilé ("The Great Secret, or Occultism Unveiled"); this, however, was only published posthumously in 1898.

Constant resumed the use of openly socialist language after the government had loosened the restrictions against socialist doctrines in 1859. From La clef on, he extensively cited his radical writings, even his infamous Bible de la liberté. He continued to develop his idea of an élite of initiates that would lead the people to its final emancipation. In several passages he explicitly identified socialism, Catholicism, and occultism.[10]

The magic propagated by Éliphas Lévi became a great success, especially after his death. That Spiritualism was popular on both sides of the Atlantic from the 1850s contributed to this success. However, Lévi diverged from spiritualism and criticized it, because he believed only mental images and "astral forces" persisted after an individual died, which could be freely manipulated by skilled magicians, unlike the autonomous spirits that Spiritualism posited.[11] His magical teachings were free from obvious fanaticisms, even if they remained rather murky; he had nothing to sell, and did not pretend to be the initiate of some ancient or fictitious secret society. He incorporated the Tarot cards into his magical system, and as a result the Tarot has been an important part of the paraphernalia of Western magicians.[12] He had a deep impact on the magic of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and later on the ex-Golden Dawn member Aleister Crowley. He was also the first to declare that a pentagram or five-pointed star with one point down and two points up represents evil, while a pentagram with one point up and two points down represents good. Lévi's ideas also influenced Helena Blavatsky and the Theosophical Society.[13] It was largely through the occultists inspired by him that Lévi is remembered as one of the key founders of the 20th-century revival of magic.

Socialist background and alleged initiation

It was long believed that the socialist Constant disappeared with the demise of the Second Republic and gave way to the occultist Éliphas Lévi. It has been argued recently, however, that this narrative was constructed at the end of the nineteenth century in occultist circles and was uncritically adopted by later scholarship. According to this argument, Constant not only developed his "occultism" as a direct consequence of his socialist and neo-catholic ideas, but he continued to propagate the realization of "true socialism" throughout his entire life.[14]

According to the narrative developed by the occultist Papus (Gérard Encausse) and cemented by the occultist biographer Paul Chacornac, Constant's turn to occultism was the result of an "initiation" by the eccentric Polish expatriate Józef Maria Hoene-Wroński. However, it has been argued that Wronski's influence had been brief, between 1852 and 1853, and superficial.[15] However, this narrative had been developed before Papus and his companions had any access to reliable information about Constant's life. This becomes most obvious in the light of the fact that Papus had tried to contact Constant by mail on January 11, 1886 – almost eleven years after his death. The two did know each other, as evidenced in Constant's 6 January 1853 letter to Hoene-Wroński, thanking him for including one of Constant's articles in Hoené-Wroński's 1852 work, Historiosophie ou science de l’histoire. In the letter Constant expresses his admiration for Hoené-Wroński's "still underappreciated genius" and calls himself his "sincere admirer and devoted disciple".[16] Later on, the construction of a specifically French esoteric tradition, in which Constant was to form a crucial link, perpetuated this idea of a clear rupture between the socialist Constant and the occultist Lévi. A different narrative was developed independently by Arthur Edward Waite, who had even less information about Constant's life.[17]

Also, a journey to London that Constant made in May 1854 did not cause his preoccupation with magic, although he seems to have been involved in practical magic for the first time. Instead, it was the aforementioned socialist-magnetistic context that formed the background of Constant's interest in magic.[18] It should also be noted that the relationship between Constant and the novelist Edward Bulwer-Lytton was not as intimate as it is often claimed.[19] In fact, Bulwer-Lytton's famous novel A Strange Story (1862) includes a rather unflattering remark about Constant's Dogme et rituel.[20][21]

Definition of magic

Lévi's works are filled with various definitions for magic and the magician:

Magic

- "To practice magic is to be a quack; to know magic is to be a sage."

- "Magic is the divinity of man conquered by science in union with faith; the true Magi are Men-Gods, in virtue of their intimate union with the divine principle."[22]

Magician

- "He looks on the wicked as invalids whom one must pity and cure; the world, with its errors and vices, is to him God's hospital, and he wishes to serve in it."

- "They are without fears and without desires, dominated by no falsehood, sharing no error, loving without illusion, suffering without impatience, reposing in the quietude of eternal thought... a Magus cannot be ignorant, for magic implies superiority, mastership, majority, and majority signifies emancipation by knowledge. The Magus welcomes pleasure, accepts wealth, deserves honour, but is never the slave of one of them; he knows how to be poor, to abstain, and to suffer; he endures oblivion willingly because he is lord of his own happiness, and expects or fears nothing from the caprice of fortune. He can love without being beloved; he can create imperishable treasures, and exalt himself above the level of honours or the prizes of the lottery. He possesses that which he seeks, namely, profound peace. He regrets nothing which must end, but remembers with satisfaction that he has met with good in all. His hope is a certitude, for he knows that good is eternal and evil transitory. He enjoys solitude, but does not fly the society of man; he is a child with children, joyous with the young, staid with the old, patient with the foolish, happy with the wise. He smiles with all who smile, and mourns with all who weep; applauding strength, he is yet indulgent to weakness; offending no one, he has himself no need to pardon, for he never thinks himself offended; he pities those who misconceive him, and seeks an opportunity to serve them; by the force of kindness only does he avenge himself on the ungrateful..."

- "Judge not; speak hardly at all; love and act."

.jpg)

Cultural references

- H. P. Lovecraft referred to Lévi twice in his novella The Case of Charles Dexter Ward.

- Angela Carter referred to Lévi in the short story "The Bloody Chamber."

- Anthony Powell quotes Lévi in his novel "The Military Philosophers".

Selected writings

- La Bible de la liberté (The Bible of Liberty), 1841

- Doctrines religieuses et sociales (Religious and Social Doctrines), 1841

- L'assomption de la femme (The Assumption of Woman), 1841

- La mère de Dieu (The Mother of God), 1844

- Le livre des larmes (The Book of Tears), 1845

- Le testament de la liberté (The Testament of Liberty), 1848

- Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magie, (Transcendental Magic, its Doctrine and Ritual), 1854–1856

- Histoire de la magie, (The History of Magic), 1860

- La clef des grands mystères (The Key to the Great Mysteries), 1861

- Fables et symboles (Stories and Images), 1862

- La science des esprits (The Science of Spirits), 1865

- Le grand arcane, ou l'occultisme dévoilé (The Great Secret, or Occultism Unveiled), 1868

- Magical Rituals of the Sanctum Regnum, 1892, 1970

- The Book of Splendours: The Inner Mysteries of Qabalism

See also

Notes and references

- ↑ Christopher McIntosh, Éliphas Lévi and the French Occult Revival, 1972.

- ↑ Strube 2016.

- ↑ Chacornac, Paul (1989) [1926]. Eliphas Lévi. Paris. p. 119.

- ↑ Strube 2016, pp. 376-383.

- ↑ Strube 2016, pp. 383-388.

- ↑ Strube 2016, pp. 418-426.

- ↑ Strube 2016, pp. 470-488.

- ↑ Strube 2016, pp. 523-563.

- ↑ Josephson-Storm 2017, p. 106.

- ↑ Strube 2016, pp. 565-589.

- ↑ Josephson-Storm 2017.

- ↑ Josephson, Jason Ānanda. “God’s Shadow” History of Religions, Vol. 52, No. 4 (May 2013), 321.

- ↑ Josephson-Storm 2017, p. 116.

- ↑ Strube, Julian (2016-03-29). "Socialist religion and the emergence of occultism: a genealogical approach to socialism and secularization in 19th-century France". Religion. 0 (0): 1–30. doi:10.1080/0048721X.2016.1146926. ISSN 0048-721X.

- ↑ Strube 2016, pp. 426-438.

- ↑ Rafał T. Prinke, Uczeń Wrońskiego - Éliphas Lévi w kręgu polskich mesjanistów, Pamiętnik Biblioteki Kórnickiej, Zeszyt 30., Red. Barbara Wysocka. 2013, p. 133

- ↑ Strube 2016, pp. 590-618.

- ↑ Strube 2016, pp. 455-470.

- ↑ C. Nelson Stewart, Bulwer Lytton as Occultist 1996:36 notes that the one surviving letter from Lévi to Lytton "would appear to be addressed to a stranger or to a very distant acquaintance" (A. E. Waite).

- ↑ Strube 2016, pp. 584-585.

- ↑ Bulwer Lytton, Edward Jones (1862). A Strange Story. 2. Leipzig: Bernhard Tauchnitz. p. 249.

Hence the author of Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magie, printed at Paris, 185-53 — a book less remarkable for tis learning than for the earnest belief of a scholar of our own day in the reality of the art of which be records of history — insists much on the necessity of rigidly observing Le Ternaire, in the number of persons who assist in an enchanter's experiments.

- ↑ Lévi, Éliphas; Blavatsky, H. P. (2007). Paradoxes of the Highest Science. Wildside Press LLC. p. 15. ISBN 9781434401069.

Sources

- Josephson-Storm, Jason (2017), The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity, and the Birth of the Human Sciences, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-40336-X

- Strube, Julian (2016), Sozialismus, Katholizismus und Okkultismus im Frankreich des 19. Jahrhunderts: Die Genealogie der Schriften von Eliphas Lévi, Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, ISBN 9783110478105

Further reading

- Bowman, Frank Paul (1969). Eliphas Lévi, visionnaire romantique. Presses Universitaires de France.

- Chacornac, Paul (1926). Eliphas Lévi: Rénovateur de l'Occultisme en France. Chacornac frères.

- McIntosh, Christopher (1975). Eliphas Lévi and the French Occult Revival. Rider.

- Mercier, Alain (1974). Eliphas Lévi et la pensée magique au XIXe siècle Alain Mercier. Seghers.

- Strube, Julian (2016). "Socialist Religion and the Emergence of Occultism: A Genealogical Approach to Socialism and Secularization in 19th-Century France." Religion. doi: 10.1080/0048721X.2016.1146926

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Éliphas Lévi. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Éliphas Lévi |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Eliphas Levi |

- Works by Éliphas Lévi at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Éliphas Lévi at Internet Archive

- Works by or about Éliphas Lévi at Internet Archive

- Online books by Lévi

- 19 Unpublished Fables by Éliphas Lévi Free download

- New English translation (2014) of Dogma of High Magic by Éliphas Lévi

- Transcendental Magic, its Doctrine and Ritual (Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magie) trans. A.E. Waite (HTML at the Wayback Machine (archived September 19, 2008), PDF )

- The Key of Mysteries (HTML)

- The Magical Ritual of the Sanctum Regnum (HTML, multiple formats)

- Extensive biography in French

- Lévi, Éliphas. Clefs Majeurs et Clavicules de Salomon ("Major Arcana and Keys of Solomon") – text online. Retrieved 19 October 2006

- Josephson, Jason Ānanda. “God’s Shadow” History of Religions, Vol. 52, No. 4 (May 2013),