Khirbet Qeiyafa

Coordinates: 31°41′47″N 34°57′26″E / 31.69639°N 34.95722°E

Western gate | |

Khirbet Qeiyafa | |

| Alternative name | Elah fortress |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 31°41′47″N 34°57′27″E / 31.6963°N 34.9575°E |

| Grid position | 146/122 PAL |

| History | |

| Founded | 10th-century BCE |

| Periods | Iron Age, Hellenistic |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 2007 – |

| Archaeologists | Yosef Garfinkel, Saar Ganor |

| Condition | ruin |

| Website | Khirbet Qeiyafa Archaeological Project |

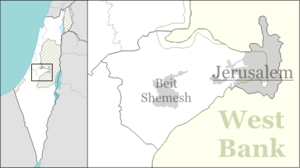

Khirbet Qeiyafa (Hebrew: חורבת קייאפה; Arabic: خربة قيافة) (also known as Elah Fortress; Hirbet Kaifeh) is the site of an ancient fortress city overlooking the Elah Valley.[1] The ruins of the fortress were uncovered in 2007,[2] near the Israeli city of Beit Shemesh, 30 km (20 mi) from Jerusalem.[3] It covers nearly 2.5 ha (6 acres) and is encircled by a 700-meter-long (2,300 ft) city wall constructed of stones weighing up to eight tons each.[4] A number of archaeologists, mainly Yosef Garfinkel and Saar Ganor, have claimed that it might be the biblical city of Sha'arayim, because of the two gates discovered on the site, or Neta'im[5] and that the large building at the center is an administrative building dating to the reign of King David, where he might have lodged at some point.[6][7] This is based on their conclusions that the site dates to the early Iron IIA, ca. 1025–975 BCE[8], a range which includes the biblical date for the Kingdom of David. Others are sceptical, and suggest it might represent either a North Israelite, Philistine or Canaanite fortress.[9] The techniques and interpretations used to reach the conclusion that Khirbet Qeiyafa was a fortress of King David have been criticised.[8]

Settlement periods

This is Iron Age II for most findings

The top layer of the fortress shows that the fortifications were renewed in the Hellenistic period.[10]

In the Byzantine period, a luxurious land villa was built on top of the Iron Age II palace and cut the older structure in two.[11]

Names

The meaning of the Arabic name of the site, Khirbet Qeiyafa, is uncertain. Scholars suggest it may mean "the place with a wide view."[12] In 1881, Palmer thought that Kh. Kîâfa meant "the ruin of tracking foot-steps".[13]

The modern Hebrew name, מבצר האלה, or the Elah Fortress was suggested by Foundation Stone directors David Willner and Barnea Levi Selavan at a meeting with Garfinkel and Ganor in early 2008. Garfinkel accepted the idea and excavation t-shirts with that name were produced for the 2008 and 2009 seasons. The name derives from the location of the site on the northern bank of Nahal Elah, one of six brooks that flow from the Judean mountains to the coastal plain.[12]

Geography

The Elah Fortress lies just inside a north-south ridge of hills separating Philistia and Gath to the west from Judea to the east. The ridge also includes the site currently identified as Tel Azekah.[10] Past this ridge is a series of connecting valleys between two parallel groups of hills. Tel Sokho lies on the southern ridge with Tel Adullam behind it. The Elah Fortress is situated on the northern ridge, overlooking several valleys with a clear view of the Judean Mountains. Behind it to the northeast is Tel Yarmut. From the topography, archaeologists believe this was the location of the cities of Adullam, Sokho, Azekah and Yarmut cited in Joshua 15:35.[10] These valleys formed the border between Philistia and Judea.

Site and excavation history

The site of Khirbet Qeiyafa was surveyed in the 1860s by Victor Guérin who reported the presence of a village on the hilltop.[14] In 1875, British surveyors noted only stone heaps at Kh. Kiafa.[15] In 1932, Dimitri Baramki, reported the site to hold a 35 square metres (380 sq ft) watchtower associated with Khirbet Quleidiya (Horvat Qolad), 200 metres (660 ft) east.[12] The site was mostly neglected in the 20th century and not mentioned by leading scholars.[2] Yehuda Dagan conducted more intense surveys in the 1990s and documented the visible remains.[12] The site raised curiosity in 2005 when Saar Ganor discovered impressive Iron Age structures under the remnants.[2]

Excavations at Khirbet Qeiyafa began in 2007, directed by Yosef Garfinkel of the Hebrew University and Saar Ganor of the Israel Antiquities Authority, and continued in 2008.[16] Nearly 600 square metres (6,500 sq ft) of an Iron Age IIA city were unearthed. Based on pottery styles and two burned olive pits tested for carbon-14 at Oxford University, Garfinkel and Ganor have dated the site to 1050–970 BCE,[2] although Israel Finkelstein contends evidence points to habitation between 1050 and 915 BCE.[17]

The initial excavation by Ganor and Garfinkel took place from August 12 to 26, 2007 on behalf of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem Institute of Archaeology. In their preliminary report at the annual ASOR conference on November 15, they presented a theory that the site was the Biblical Azekah, which until then had been exclusively associated with Tell Zakariya.[18] In Sept. of 2008, Joseph Silver, the chief funder of the excavation, while walking around the exterior of the city wall in the SE part with Garfinkel and Ganor, identified features in the city wall similar to the features found by Garfinkel and Ganor in the western gate, and stated that it was a second gate[19]. In November, with volunteers from the Bnai Akiva youth organization, the area was cleared and an excavation organized by Garfinkel and Ganor confirmed the architecture of the second gate. The identification provides a solid basis (though not definitive and not without debate) for identifying the site as biblical Sha'arayim ("two gates" in Hebrew).[2]

In 2015 a plan to build a neighborhood on the site was cancelled, to enable the archaeological dig to go forward.[20]

Debate on United Monarchy

Discoveries at Khirbet Qeiyafa are significant to the debate on archaeological evidence and historicity of the biblical account of the United Monarchy at the beginning of Iron Age II.[21] Three major hypotheses were advanced by Garfinkel, Nadav Na’aman and Ido Koch, and Israel Finkelstein. Garfinkel said in 2010 that the debate could not "be answered by the Qeiyafa excavations." He is of the opinion that "what is clear, however, is that the kingdom of Judah existed already as a centrally organized state in the tenth century BCE".[22][23][24] Nadav Na’aman and Ido Koch held that the ruins were Canaanite, based on strong similarities with the nearby Canaanite excavations at Beit Shemesh. Finkelstein and Alexander Fantalkin, maintained that the site shows affiliations with a North Israelite entity.[9] In 2015 Finkelstein and Piasetsky specifically criticised the previous statistical treatment of radio-carbon dating at Khirbet Qeiyafa and also whether it was prudent to ignore results from neighboring sites.[25] As no archaeological finds were found that could corroborate claims of the existence of a magnificent biblical kingdom, various scholars have advanced the opinion that the kingdom was no more than a small tribal entity.

Releasing the preliminary dig reports for the 2010 and 2011 digging seasons at Khirbet Qeiyafa, the Israel Antiquities Authority stated: "The excavations at Khirbat Qeiyafa clearly reveal an urban society that existed in Judah already in the late eleventh century BCE. It can no longer be argued that the Kingdom of Judah developed only in the late eighth century BCE or at some other later date."[26]

Identification

In 2010, Gershon Galil of the University of Haifa identified Khirbet Qeiyafa as the "Neta'im" of 1 Chronicles 4:23, due to its proximity to Khirbet Ğudrayathe (biblical Gederah). The inhabitants of both cities were said to be "potters" and "in the King's service", a description that is consistent with the archeological discoveries at that site.[27]

Yehuda Dagan of the Israel Antiquities Authority also disagrees with the identification as Sha'arayim. Dagan believes the ancient Philistine retreat route, after their defeat in the battle at the Valley of Elah (1 Samuel 17:52), more likely identifies Sha'arayim with the remains of Khirbet esh-Shari'a. Dagan proposes that Khirbet Qeiyafa be identified with biblical Adithaim (Joshua 15:36).[12] Nadav Na'aman of Tel Aviv University doubts that Sha'arayim means "two gates" at all, citing multiple scholarly opinions that the suffix -ayim in ancient place names is not the dual suffix used for ordinary words.[28]

The fortifications at Khirbet Qeiyafa predate those of contemporary Lachish, Beersheba, Arad, and Timnah. All these sites have yielded pottery dated to early Iron Age II. The parallel valley to the north, mentioned in Samuel I, runs from the Philistine city of Ekron to Tel Beit Shemesh. The city gate of the Elah Fortress faces west with a path down to the road leading to the sea, and was thus named "Gath Gate" or "Sea Gate." The 23-dunam (5.7-acre) site is surrounded by a casement wall and fortifications.[23]

Garfinkel suggests that it was a Judean city with 500–600 inhabitants during the reign of David and Solomon.[23][29][30] Based on pottery finds at Qeiyafa and Gath, archaeologists believe the sites belonged to two distinct ethnic groups. "The finds have not yet established who the residents were," says Aren Maeir, a Bar Ilan University archaeologist digging at Gath. "It will become more clear if, for example, evidence of the local diet is found. Excavations have shown that Philistines ate dogs and pigs, while Israelites did not. The nature of the ceramic shards found at the site suggest residents might have been neither Israelites nor Philistines but members of a third, forgotten people."[31] Evidence that the city was not Philistine comes from the private houses that abut the city wall, an arrangement that was not used in Philistine cities.[32] There is also evidence of equipment for baking flat bread and hundreds of bones from goats, cattle, sheep, and fish. Significantly, no pig bones have been uncovered, suggesting that the city was not Philistine or Canaanite.[32][33] Nadav Na'aman of Tel Aviv University nevertheless associates it with Philistine Gath, citing the necessity for further excavations as well as evidence from Bet Shemesh whose inhabitants also avoided eating pork, yet were associated with Ekron.[34] Na'aman proposed identification with the Philistine city of Gob.[34]

Yigal Levin has proposed that the ma'gal (מעגל) or "circular camp" of the Israelites which is mentioned in the story of David and Goliath (1 Samuel 17:20) was described this way because it fitted the circular shape of the nearby Khirbet Qeiyafa.[35] Levin argues that the story of David and Goliath is set decades before Khirbet Qeiyafa was built and so the reference to Israel's encampment at the ma'gal probably does "not represent any particular historical event at all". But when the story was composed centuries later, the round structure of Khirbet Qeiyafa "would still have been visible and known to the author of 1 Samuel 17", who "guessed its function, and worked it into his story".[35]

Archaeological finds

General outline

The site consists of a lower city of about 10 hectares and an upper city of about 3 hectares (7.4 acres) surrounded by a massive defensive wall ranging from 2–4 metres (6 ft 7 in–13 ft 1 in) tall. The walls are built in the same manner as the walls of Hazor and Gezer, formed by a casemate (a pair of walls with a chamber in between).[32]

At the center of the upper city is a large rectangular enclosure with spacious rooms on the south, equivalent to similar enclosures found at royal cities such as Samaria, Lachish, and Ramat Rachel.

On the southern slope, outside the city, there are Iron Age rock-cut tombs.

The site, according to Garfinkel, has "a town plan characteristic of the Kingdom of Judah that is also known from other sites, e.g., Beit Shemesh, Tell en-Nasbeh, Tell Beit Mirsim and Beersheba. A casemate wall was built at all of these sites and the city’s houses next to it incorporated the casemates as one of the dwelling's rooms. This model is not known from any Canaanite, Philistine or Kingdom of Israel site."[36]

The site is massively fortified, "including the use of stones that weigh up to eight tons apiece."[36]

Marked jar handles

"500 jar handles bearing a single finger print, or sometimes two or three, were found. Marking jar handles is characteristic of the Kingdom of Judah and it seems this practice has already begun in the early Iron Age IIA."[36]

Excavation areas

Area "A" extended 5×5 metres and consists of two major layers: Hellenistic above, and Iron Age II below.[37]

Area "B" contains four squares, about 2.5 metres deep from top-soil to bedrock, and also features both Hellenistic and Iron Age layers.[37] Surveys on the surface have also revealed sherds from the early and middle Bronze Ages, as well as from the Persian, Roman, Byzantine, early Islamic, Mameluke and Ottoman periods.[12]

The Hellenistic/upper portion of the wall was built with small rocks atop the Iron-II lower portion, consisting of big boulders in a casemate design. Part of a structure identified as a city gate was uncovered, and some of the rocks where the wall meets this gate are estimated to weigh 3 to 5 tons.[37] The lower phase was built of especially large stones, 1–3 meters long, and the heaviest of them weigh 3–5 tons. Atop these stones is a thin wall, c. 1.5 meters thick; small and medium size fieldstones were used in its construction. These two fortification phases rise to a height of 2–3 meters and standout at a distance, evidence of the great effort that was invested in fortifying the place.[37]

Ishba'al inscription

In 2012 an inscription in Canaanite alphabetic script was found on the shoulder of a ceramic jar. The inscription read "Išbaʿal son of Beda" and was dated to Iron Age IIA.

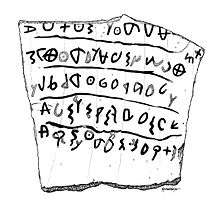

Khirbet Qeiyafa ostracon

A 15-by-16.5-centimetre (5.9 in × 6.5 in) ostracon, a trapezoid-shaped potsherd with five lines of text,[38] was discovered during excavations at the site in 2008.[38]

Although the writing on the ostracon is poorly preserved and difficult to read, Émile Puech of the École Biblique et Archéologique Française proposed that it be read:

- 1 Do not oppress, and serve God … despoiled him/her

- 2 The judge and the widow wept; he had the power

- 3 over the resident alien and the child, he eliminated them together

- 4 The men and the chiefs/officers have established a king

- 5 He marked 60 [?] servants among the communities/habitations/generations

and understood the ostracon as a locally written copy of a message from the capital informing a local official of the ascent of Saul to the throne.[39] Puech considered the language to be Canaanite or Hebrew without Philistine influence.[40]

Gershon Galil of Haifa University proposed the following translation:

- 1 you shall not do [it], but worship (the god) [El]

- 2 Judge the sla[ve] and the wid[ow] / Judge the orph[an]

- 3 [and] the stranger. [Pl]ead for the infant / plead for the po[or and]

- 4 the widow. Rehabilitate [the poor] at the hands of the king

- 5 Protect the po[or and] the slave / [supp]ort the stranger.[38]

On January 10, 2010, the University of Haifa issued a press release stating that the text was a social statement relating to slaves, widows and orphans. According to this interpretation, the text "uses verbs that were characteristic of Hebrew, such as ‘śh (עשה) ("did") and ‘bd (עבד) ("worked"), which were rarely used in other regional languages. Particular words that appear in the text, such as almanah ("widow") are specific to Hebrew and are written differently in other local languages. The content itself, it is argued, was also unfamiliar to all the cultures in the region besides that of Hebrew society. It was further maintained that the present inscription yielded social elements similar to those found in the biblical prophecies markedly different from those current in by other cultures that write of the glorification of the gods and taking care of their physical needs."[38][41] Gershon Galil claims that the language of inscription is Hebrew and that 8 out of 18 words written on inscription are exclusively biblical. He also claimed that 30 major archeological scholars do support this thesis.[42]

Other readings are possible, however, and the official excavation report presented many possible reconstructions of the letters without attempting a translation.[43] The inscription is written left to right in a script which is probably Early Alphabetic/Proto Phoenician,[43][44] though Christopher Rollston and Demsky consider that it might be written vertically.[44] Early Alphabetic differs from old Hebrew script and its immediate ancestor.[44] Rollston also disputes the claim that the language is Hebrew, arguing that the words alleged to be indicative of Hebrew either appear in other languages or don't actually appear in the inscription.[44]

Millard believes the language of the inscription is Hebrew, Canaanite, Phoenician or Moabite and it most likely consists of a list of names written by someone unused to writing.[45] Levy and Pluquet give several readings as a list of personal names using a computer-assisted approach.[46] Hebrew University archaeologist Amihai Mazar said the inscription was very important, as it is the longest Proto-Canaanite text ever found.[47]

In 2010 the ostracon was placed on display in the Iron Age gallery of the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.[41]

Shrines

Rooms used for cultic purposes

In May 2012 archeologists announced the discovery of three large rooms that were likely used as cultic shrines. While the Canaanites and Philistine practiced their cults in separate temples and shrines, they did not have separate rooms within the buildings dedicated only to religious rituals. This may suggest that the rooms did not belong to these two cultures. According to Garfinkel the decorations of cultic rooms lack any human figurines. He suggested "that the population of Khirbet Qeiyafa observed at least two biblical bans, on pork and on graven images, and thus practiced a different cult than that of the Canaanites or the Philistines,"[48]

Portable shrines

Three small portable shrines were also discovered. The smaller shrines are boxes shaped with different decorations showing impressive architectonic and decorative styles. Garfinkel suggested the existence of a biblical parallel regarding the existence of such shrines (2 Samuel 6). One of the shrines is decorated with two pillars and a lion. According to Garfinkel, the style and the decoration of these cultic objects are very similar to the Biblical description of some features of Solomon's Temple.[49]

Palace and pillared storehouse

On July 18, 2013, the Israel Antiquities Authority issued a press release about the discovery of a structure believed to be King David’s palace in the Judean Shephelah.[7] The archaeological team uncovered two large buildings dated to the tenth century BCE, one a large palatial structure and the other a pillared store room with hundreds of stamped storage vessels. The claim that the larger structure may be one of King David's palaces led to significant media coverage, while skeptics accused the archaeologists of sensationalism.[50] Aren Maeir, an archaeologist at Bar Ilan University, pointed out that existence of King David’s monarchy is still unproven and some scholars believe the buildings could be Philistine or Canaanite.[51][52] The massive structure located on a hill in the center of the city was decorated with alabaster imported from Egypt. On one side it offered a view of the two city gates, Ashdod and the Mediterranean, and on the other, the Elah Valley. During the Byzantine era, a wealthy farmer built a home on the site, cutting the palace in two.[11]

See also

References

- ↑ Rabinovitch, Ari (October 30, 2008). "Archaeologists report finding oldest Hebrew text". Reuters. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Garfinkel, Yosef; Ganor, Saar (2008). "Khirbet Qeiyafa: Sha'arayim" (PDF). Journal of Hebrew Scriptures. 8. ISSN 1203-1542. Archived from the original (pdf) on October 4, 2011. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ↑ Catling, Chris (January 6, 2009). "Elah city-fortress, Khirbet Qeiyafa". Current World Archaeology (33): 8. Retrieved November 16, 2011.

- ↑ Kalman, Matthew (October 31, 2008). "'Proof' David slew Goliath found as Israeli archaeologists unearth 'oldest ever Hebrew text'". Daily Mail. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ↑ "Khirbet Qeiyafa Identified as Biblical 'Neta'im'". Science Daily. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- ↑ "Have Archaeologists Found King David's Palace?". Bible Gateway. 31 July 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- 1 2 "King David's Palace at Khirbet Qeiyafa?". Bible History Daily. Archived from the original on 1 August 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- 1 2 Finkelstein, Israel; Fantalkin, Alexander (2012). "Khirbet Qeiyafa: An Unsensational Archaeological and Historical Interpretation" (PDF). TEL AVIV, Vol. 39. pp. 38–63. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

We cannot close this article without a comment on the sensational way in which the finds of Khirbet Qeiyafa have been communicated to both the scholarly community and the public. The idea that a single, spectacular finding can reverse the course of modern research and save the literal reading of the biblical text regarding the history of ancient Israel from critical scholarship is an old one. Its roots can be found in W.F. Albright’s assault on the Wellhausen School in the early 20th century, an assault that biased archaeological, biblical and historical research for decades. This trend—in different guises—has resurfaced sporadically in recent years, with archaeology serving as a weapon to quell progress in critical scholarship. Khirbet Qeiyafa is the latest case in this genre of craving a cataclysmic defeat of critical modern scholarship by a miraculous archaeological discovery

- 1 2 Julia Fridman, 'Crying King David: Are the ruins found in Israel really his palace? ,' at Haaretz, 26 August 2013."Not all agree that the ruins found in Khirbet Qeiyafa are of the biblical town Shaarayim, let alone the palace of ancient Israel's most famous king."

- 1 2 3 Selavan, Barnea Levi (August 2008). "Elah Fortress – A short history of the site". Foundation Stone. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- 1 2 A King's View of Khirbet Qeiyafa, Jerusalem Post

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Dagan, Yehuda (2009). "Khirbet Qeiyafa in the Judean Shephelah: Some Considerations" (pdf). Tel Aviv: Journal of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University. 36: 68–81.

- ↑ Palmer, 1881, p. 308

- ↑ Khirbet Kaïafa, in Guérin, 1869, pp. 331–332

- ↑ Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, p. 118

- ↑ "Khirbet Qeiyafa Archaeological Project". Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ↑ Finkelstein, Israel; Piasetzky, Eli (June 2010). "Khirbet Qeiyafa: Absolute Chronology" (PDF). Tel Aviv: Journal of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University. 37 (1): 84–88. doi:10.1179/033443510x12632070179621. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 April 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ↑ "ASOR 2007 Conference abstracts" (PDF). Boston University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ↑ B.A.R., vol.43, no.1 pp.37-43, 59

- ↑ Hasson, Nir (10 December 2015). "Beit Shemesh Scraps Plan for New Neighborhood Near Archaeological Site". Haaretz. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- ↑ Lipschits, Oded (2014). "The History of Israel in the Biblical Period". In Berlin, Adele; Brettler, Marc Zvi. The Jewish Study Bible (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199978465.

- ↑ "Archaeology: What an Ancient Hebrew Note Might Mean", Govier, Gordon, Christianity Today 1/18/2010

- 1 2 3 Shtull, Asaf (21 July 1993). "The Keys to the Kingdom". Haaretz. Retrieved 2011-07-14.

- ↑ Garfinkel, Yosef (May–June 2011). "The Birth & Death of Biblical Minimalism". Biblical Archaeology Review. 37 (03).

- ↑ Finkelstein, Israel; Piasetzky, Eli (2015). "Radiocarbon dating Khirbet Qeiyafa and the Iron I–IIA phases in the Shephelah: Methodological comments and a Bayesian model". Radiocarbon, Vol 57, Nr 5. pp. 891–907.

- ↑ "Israel Antiquities Authority". Hadashot-esi.org.il. Archived from the original on 23 June 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ↑ "Khirbet Qeiyafa identified as biblical "Neta'im"". University of Haifa. March 4, 2010. Retrieved July 14, 2011.

- ↑ Nadav Na'aman (2008). "Shaaraim — the gateway to the Kingdom of Judah" (PDF). Journal of Hebrew Scriptures. 8 (24).

- ↑ Ethan Bronner (2008-10-29). "Find of Ancient City Could Alter Notions of Biblical David". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-11-05.

- ↑ "Have Israeli archaeologists found world's oldest Hebrew inscription?". Haaretz. Associated Press. October 30, 2008. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ↑ Friedman, Matti (October 30, 2008). "Israeli Archaeologists Find Ancient Text". AOL news. Associated Press. Archived from the original on November 3, 2008.

- 1 2 3 Draper, Robert (December 2010). "David and Solomon". National Geographic. Retrieved 2011-07-14.

- ↑ Garfinkel, Yosef (2010). "Khirbet Qeiyafa after Four Seasons of Excavations" (PDF). Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- 1 2 Na'aman, Nadav (2008). "In search of the ancient name of Khirbet Qeiyafa". The Journal of Hebrew Scriptures. ISSN 1203-1542. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- 1 2 Levin, Yigal (2012). "The Identification of Khirbet Qeiyafa: A New Suggestion". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. Retrieved November 7, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Garfinkel, Yossi; Sa'ar Ganor; Michael Hasel (19 April 2012). "Horvat Qeiyafa: The Fortification of the Border of the Kingdom of Judah". Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel (HA-ESI). 124. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Garfinkel, Yossi; Ganor, Sa'ar. "Horvat Qeiyafa: The Fortification of the Border of the Kingdom of Judah". Israel Antiquities Authority. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 "Most ancient Hebrew biblical inscription deciphered". University of Haifa. January 10, 2010. Archived from the original on October 5, 2011. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ↑ Leval, Gerard (2012). "Ancient Inscription Refers to Birth of Israelite Monarchy." Biblical Archaeology Review. May/June 2012, 41-43, 70.

- ↑ Émile Puech (2010). "l'ostracon de Khirbet Qeyafa et les débuts de la royauté en Israël". Revue Biblique. 117 (2): 162–184.

On a affaire au premier document de quelque longueur, en langue cananéenne ou hébraïque, bien daté et de quelque importance pour l'histoire de la langue, de l'orthographe et pour l'histoire en général, sans une quelconque influence philistine.

- 1 2 "Qeiyafa Ostracon Chronicle". Khirbet Qeiyafa Archaeological Project. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ↑ "The keys to the kingdom". Haaretz.com. 6 May 2011. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- 1 2 Misgav, Haggai; Garfinkel, Yosef; Ganor, Saar (2009). "The Ostracon". In Garfinkel, Yosef and Ganor, Saar. Khirbet Qeiyafa, Vol. 1: Excavation Report 2007–2008. Jerusalem. pp. 243–257. ISBN 978-965-221-077-7. Cited in Rollston, Christopher (June 2011). "The Khirbet Qeiyafa Ostracon: Methodological Musings and Caveats". Tel Aviv: Journal of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University. 38 (1): 67–82. doi:10.1179/033443511x12931017059387.

- 1 2 3 4 Rollston, Christopher (June 2011). "The Khirbet Qeiyafa Ostracon: Methodological Musings and Caveats". Tel Aviv: Journal of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University. 38 (1): 67–82. doi:10.1179/033443511x12931017059387.

- ↑ Alan Millard (2011). "The ostracon from the days of David found at Khirbet Qeiyafa". Tyndale Bulletin. 62 (1): 1–14.

- ↑ Eythan Levy and Frédérik Pluquet (2007). "Computer experiments on the Khirbet Qeiyafa ostracon". Digital Scholarship in the Humanities.

- ↑ "'Oldest Hebrew script' is found". BBC News. October 30, 2008. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ↑ "Archaeologist finds first evidence of cult in Judah at time of King David". Phys.org. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ↑ "Earliest Evidence of Biblical Cult Discovered". Discovery News. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ↑ "3,000-year-old palace in Israel linked to biblical King David." NBC News, July 19, 2013. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- ↑ Schultz, Colin (July 22, 2013). "Archaeologists Just Found the Biblical King David's Palace. Maybe". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ Kumar, Anugarh (July 22, 2013). "Archaeologists Claim Discovery of King David's Palace". Christian Post. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

Bibliography

- Conder, Claude Reignier; Kitchener, H. H. (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 3. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Guérin, Victor (1869). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). 1: Judee, pt. 3. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Palmer, E. H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Khirbet Qeiyafa. |

- AFOB (Archaeological Fieldwork Opportunities Bulletin) Online Listing for Khirbet Qeiyafa

- The ʾIšbaʿal Inscription from Khirbet Qeiyafa in Jstor

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 17: IAA, Wikimedia commons