Bosnian mujahideen

| El Mudžahid | |

|---|---|

| |

| Active | 1992–95 |

| Disbanded | 1995 |

| Country |

|

| Branch | Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | 1,000–2,000 (estimates vary, 500–5,000) |

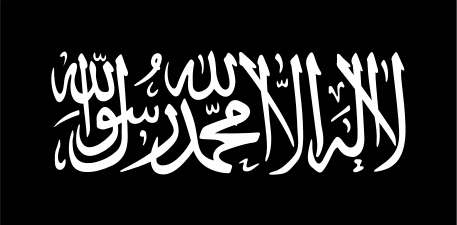

| Colors | Black, white, green |

| Mascot(s) | Scimitar |

| Equipment | AK-47, PKM, various surplus Eastern Bloc and civilian weapons such as hunting rifles and shotguns |

| Engagements |

|

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Abdelkader Mokhtari |

Bosnian mujahideen (Bosnian: Bosanski mudžahedini), also called El Mudžahid (from Arabic: مجاهد, mujāhid), were foreign Muslim volunteers who fought on the Bosniak (Bosnian Muslim) side during the 1992–95 Bosnian War. These first arrived in central Bosnia in the second half of 1992 with the aim of fighting for Islam (as mujahideen), helping their Bosnian Muslim co-religionists to defend themselves from the Serb and Croat forces. Mostly they came from North Africa, the Near East and the Middle East. Estimates of their numbers vary from 500–5,000.

Bosnian War

In the breakup of Yugoslavia in 1991, Slovenia and Croatia declared independence. War broke out in Croatia between the Croatian Army and the breakaway Serb Krajina. Meanwhile, the Bosnian Muslim leadership opted for independence. Serbs established autonomous provinces and Bosnian Croats took similar steps. The war broke out in April 1992.

Muslim countries came to support the Bosnian Muslims and an independent Bosnia and Herzegovina. Support came from Iran, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and other Muslim countries. There were also Islamist organizations and Muslim non-profit organizations and charitable trusts that supported the Bosnian Muslims. Muslim foreign fighters joined the Bosnian Muslim side.

ICG estimated 2,000–5,000 foreign Muslim fighters.[1] Charles R. Shrader estimated up to 4,000.[2] J. M. Berger estimated 1,000–2,000.[3] Another estimation is 3,000 foreign Islamic fighters.[4] CSIS notes that estimates range from 500–5,000, but mostly 1,000–2,000.[5]

Volunteer mujahideen arrived from all around the world,[6] including Afghanistan,[7] Egypt,[3] France,[6] Indonesia,[6] Iraq,[6] Lebanon,[8] Malaysia,[6] Morocco,[6] Russia,[6] Saudi Arabia,[6] Spain,[6] Thailand,[6] Turkey,[9] the United Kingdom,[6] the United States[6] and Yemen.[6] The Bosnian mujahideen were primarily from Iran, Afghanistan and Arab countries.[4]

Foreign mujahideen arrived in central Bosnia in the second half of 1992 with the aim of fighting for Islam, helping their Bosnian Muslim co-religionists to defend themselves from the Serb and Croat forces. Mostly they came from North Africa, the Near East and the Middle East. Some originally went as humanitarian workers,[10] while some of them were considered criminals in their home countries for illegally travelling to Bosnia and becoming soldiers. On 13 August 1993, the Bosnian government officially organized foreign volunteers into the detachment known as El Mudžahid in order to impose control and order. Initially, the foreign mujahideen gave food and other basic necessities to the local Muslim population, who were deprived of such by the Serb forces. Once hostilities broke out between the Bosnian government and the Croat forces (HVO), the mujahideen also participated in battles against the HVO alongside ARBiH units.[11]

The foreign mujahideen recruited local young men, offering them military training, uniforms and weapons. As a result, some Bosniaks joined the foreign mujahideen and in the process became local mujahideen.[11] They imitated the foreigners in both dress and behaviour, to such an extent that it was sometimes, according to the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) documentation in subsequent war crimes trials, "difficult to distinguish between the two groups". For that reason, the ICTY has used the term "Mujahideen" (which they spell Mujahedin) for both fighters from Arab countries, and also local Muslims who joined the mujahideen units.[12]

They quickly attracted heavy criticism from people who claimed their presence was evidence of violent Islamic fundamentalism in Europe. The foreign volunteers even became unpopular with many of the Bosniak population, because the Bosnian army had thousands of troops and had no need for more soldiers, but rather for arms. Many Bosnian Army officers and intellectuals were suspicious of the foreign volunteers arrival in the central part of the country, because they came from Split and Zagreb in Croatia, and were passed through the self-proclaimed Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia without problems, unlike Bosnian Army soldiers who were regularly arrested by Croat forces.

The first mujahideen training camp was located in Poljanice next to the village of Mehurici, in the Bila valley, Travnik municipality. The mujahideen group established there included mujahideen from Arab countries as well as some Bosniaks. The mujahideen from Poljanice camp were also established in the towns of Zenica and Travnik and, from the second half of 1993 onwards, in the village of Orasac, also located in the Bila valley.[11][13]

The military effectiveness of the mujahideen is disputed. However, former U.S. Balkans peace negotiator Richard Holbrooke said in an interview that he thought "the Muslims wouldn't have survived without this" help, as at the time a U.N. arms embargo diminished the Bosnian government's fighting capabilities. In 2001, Holbrooke called the arrival of the mujahideen "a pact with the devil" from which Bosnia still is recovering.[14] On the other hand, according to general Stjepan Šiber, the highest ranking ethnic Croat in the Bosnian Army, the key role in foreign volunteers arrival was played by Tuđman and Croatian counter-intelligence with the aim to justify the involvement of Croatia in the Bosnian War and the crimes committed by Croat forces. Although the Bosnian President Alija Izetbegović regarded them as symbolically valuable as a sign of the Muslim world's support for Bosnia, they appear to have made little military difference and became a major political liability.[15]

Sakib Mahmuljin, a top Bosnian general, has stated that the mujahideen sent 28 severed heads of POW Bosnian Serb soldiers to Bosnian President Alija Izetbegović and Iran.[16]

Relationship to the Bosnian Army

ICTY found that there was one battalion-sized unit called El Mudžahid (El Mujahid). It was established on 13 August 1993, by the Bosnian Army, which decided to form a unit of foreign fighters in order to impose control over them as the number of the foreign volunteers started to increase.[17] The El Mudžahid unit was initially attached to and supplied by the regular Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBiH), even though they often operated independently as a special unit.[18]

According to the ICTY indictment of Rasim Delić, Commander of Main Staff of the Bosnian army (ARBiH), after the formation of the 7th Muslim Brigade on 19 November 1992, the El Mudžahid were subordinated within its structure. According to a UN communiqué of 1995, the El Mudžahid battalion was "directly dependent on Bosnian staff for supplies" and for "directions" during combat with the Serb forces.[19] The issue has formed part of two ICTY war crimes trials against two former senior officials in the Army of Bosnia and Herzegovina on the basis of superior criminal responsibility. In its Trial Chamber judgement in the case of ICTY v. Enver Hadžihasanović, commander of the ARBiH 3rd Corps (who was later made part of the joint command of the ARBiH and was the Chief of the Supreme Command Staff), and Amir Kubura, commander of the 7th Muslim Brigade of the 3rd Corps of the ARBiH, the Trial Chamber found that

the foreign Mujahedin established at Poljanice camp were not officially part of the 3rd Corps or the 7th Brigade of the ARBiH. Accordingly, the Prosecution failed to prove beyond reasonable doubt that the foreign Mujahedin officially joined the ARBiH and that they were de iure subordinated to the Accused Enver Hadžihasanović and Amir Kubura.[11]

It also found that

there are significant indicia of a subordinate relationship between the Mujahedin and the Accused prior to August 13, 1993. Testimony heard by the Trial Chamber and, in the main, documents tendered into evidence demonstrate that the ARBiH maintained a close relationship with the foreign Mujahedin as soon as these arrived in central Bosnia in 1992. Joint combat operations are one illustration of that. In Karaula and Visoko in 1992, at Mount Zmajevac around mid-April 1993 and in the Bila valley in June 1993, the Mujahedin fought alongside ARBiH units against Bosnian Serb and Bosnian Croat forces."[11]

However, the ICTY Appeals Chamber in April 2008 concluded that the relationship between the 3rd Corps of the Bosnian Army headed by Hadžihasanović and the El Mudžahid detachment was not one of subordination but was instead close to overt hostility since the only way to control the detachment was to attack them as if they were a distinct enemy force.[17]

Propaganda

Although Serb and Croat media created much controversy about alleged war crimes committed by the squad, no indictment was issued by International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia against any of these foreign volunteers. The only foreign person convicted of war crimes was Swedish neo-Nazi Jackie Arklov, who fought in the Croatian army (first convicted by a Bosnian court, later by a Swedish court). According to the ICTY verdicts, Serb propaganda was very active, constantly propagating false information about the foreign fighters in order to inflame anti-Muslim hatred among Serbs. After the takeover of Prijedor by Serb forces in 1992, Radio Prijedor propagated Serb nationalistic ideas characterising prominent non-Serbs as criminals and extremists who should be punished. One example of such propaganda was the derogatory language used for referring to non-Serbs such as "Mujahedin", "Ustaše" or "Green Berets", although at the time there were no foreign volunteers in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The ICTY concluded in the Milomir Stakić verdict that, Mile Mutić, the director of the local paper Kozarski Vjesnik and the journalist Rade Mutić regularly attended meetings of Serb politicians (local authorities) in order to be informed about the next steps for spreading propaganda.[20][21]

Another example of propaganda about "Islamic holy warriors" is presented in the ICTY Kordić and Čerkez verdict for war crimes and crimes against humanity committed by Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia leadership on Bosniak civilians. Gornji Vakuf was attacked by Croatian Defence Council (HVO) in January 1993 followed by heavy shelling of the town by Croat artillery. During cease-fire negotiations at the Britbat HQ in Gornji Vakuf, Colonel Andrić, representing the HVO, demanded that the Bosnian forces lay down their arms and accept HVO control of the town, threatening that if they did not agree he would flatten Gornji Vakuf to the ground.[22][23] The HVO demands were not accepted by the Bosnian Army and the attack continued, followed by massacres on Bosnian Muslim civilians in the neighbouring villages of Bistrica, Uzričje, Duša, Ždrimci and Hrasnica.[24][25] The shelling campaign and the attacks during the war resulted in hundreds of injured and killed, mostly Bosnian Muslim civilians. Although Croats often cited it as a major reason for the attack on Gornji Vakuf in order to justify attacks and massacres on civilians, the commander of the UN Britbat company claimed that there were no Muslim "holy warriors" in Gornji Vakuf and that his soldiers did not see any.[22]

According to Predrag Matvejević, the number of Arab volunteers who came to help the Bosnian Muslims, "was much smaller than the number presented by Serb and Croat propaganda".[15]

After the war

In 1995, veterans of the Bosnian mujahideen established the Active Islamic Youth, regarded the most dangerous of the Islamist groups in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[26]

Citizenship controversy

The foreign mujahideen were required to leave the Balkans under the terms of the 1995 Dayton Agreement, but many stayed. Although the U.S. State Department report suggested that the number could be higher, an unnamed SFOR official said allied military intelligence estimated that no more than 200 foreign-born militants actually lived in Bosnia in 2001, of whom around 30 represent a hard-core group with direct or indirect links to terrorism.[14][27]

In September 2007, 50 of these individuals had their citizenship status revoked. Since then 100 more individuals have been prevented from claiming citizenship rights. 250 more were under investigation, while the body which is charged to reconsider the citizenship status of the foreign volunteers in the Bosnian War, including Christian fighters from Russia and Western Europe, states that 1,500 cases will eventually be examined.

War crimes trials

It is alleged that mujahideen participated in a few incidents considered to be war crimes according to the international law. However no indictment was issued by the ICTY against them, but a few Bosnian Army officers were indicted on the basis of command responsibility.

Both Amir Kubura and Enver Hadžihasanović (the indicted Bosnian Army officers) were found not guilty on all counts related to the incidents involving mujahideen.[17] The judgments in the cases of Hadžihasanović and Kabura concerned a number of events involving mujahideen. On June 8, 1993, Bosnian Army attacked Croat forces in the area of Maline village as a reaction to the massacres committed by Croats in nearby villages of Velika Bukovica and Bandol on June 4. After the village of Maline was taken, a military police unit of the 306th Brigade of Bosnian Army arrived in Maline. These policemen were to evacuate and protect the civilians in the villages taken by the Bosnian Army. The wounded were left on-site and around 200 people, including civilians and Croat soldiers, were taken by the police officers towards Mehurici. The commander of the 306th Brigade authorised the wounded be put onto a truck and transported to Mehurici. Suddenly, a number of mujahideen stormed the village of Maline. Even though the commander of the Bosnian Army 306th Brigade forbade them to approach, they did not submit. The 200 villagers who were being escorted to Mehurici by the 306th Brigade military police were intercepted by the mujahideen in Poljanice. They took 20 military-aged Croats and a young woman wearing a Red Cross armband. The prisoners were taken to Bikoci, between Maline and Mehurici. 23 Croatian soldiers and the woman were executed in Bikoci while they were being held prisoner.[28]

The ICTY indictment of Rasim Delić, also treats incidents related to mujahideen during the summer of 1995, such as the murder of two Serb soldiers on 21 July 1995 as part of Operation Miracle, the murder of a Serb POW at the Kamenica prison camp on 24 July 1995, and events related to 60 Serb soldiers captured during the Vozuća battle that are missing and presumed to have been killed by foreign volunteers.[29]

In 2015, former Human Rights Minister and Federation BiH Vice President Mirsad Kebo talked about numerous war crimes committed against Serbs by mujahideen in Bosnia and their links with current and past Muslim officials including former and current presidents of federation and presidents of parliament based on war diaries and other documented evidence. He gave evidence to the BiH federal prosecutor.[30][31][32][33]

Links to Al-Qaeda

US intelligence and phone calls intercepted by the Bosnian government show communication between Al-Qaeda commanders and Bosnian mujahideen.[34] Several of the mujahideen were connected to Al-Qaeda.[34] Osama Bin Laden sent resources to the Bosnian mujahideen.[34] Two of the five 9/11 hijackers, childhood friends Khalid al-Mihdhar and Nawaf al-Hazmi, had been Bosnian mujahideen.[35] Nasser bin Ali al-Ansi, a senior leader of the Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, had fought in Bosnia in 1995.[36] Bosnian Salafi leader and mujahideen veteran Bilal Bosnić was in 2015 sentenced to seven years in prison for public incitement to terrorist activities, recruitment of terrorists and organization of a terrorist group.[37]

Following the end of the Bosnian War and, especially, the links between the mujahideen, al-Qaeda and the radicalization of some European Muslims was more widely discussed. In a 2005 interview with U.S. journalist Jim Lehrer, Holbrooke stated:

There were over 1,000 people in the country who belonged to what we then called Mujahideen freedom fighters. We now know that that was al-Qaida. I'd never heard the word before, but we knew who they were. And if you look at the 9/11 hijackers, several of those hijackers were trained or fought in Bosnia. We cleaned them out, and they had to move much further east into Afghanistan. So if it hadn't been for Dayton, we would have been fighting the terrorists deep in the ravines and caves of Central Bosnia in the heart of Europe.[38]

Evan Kohlmann wrote: "Some of the most important factors behind the contemporary radicalization of European Muslim youth can be found in Bosnia-Herzegovina, where the cream of the Arab mujahideen from Afghanistan tested their battle skills in the post-Soviet era and mobilized a new generation of pan-Islamic revolutionaries". He also noted that Serbian and Croatian sources about the subject are "pure propaganda" based on their historical hatred for Bosniaks "as Muslim aliens in the heart of Christian lands".[39]

According to the Radio Free Europe research "Al-Qaeda In Bosnia-Herzegovina: Myth Or Present Danger", Bosnia is no more related to the potential terrorism than any other European country.[39]

Islamism and Islamic terrorism

In 2007, Juan Carlos Antúnez in an analysis of the phenomenon of Wahhabism in Bosnia concluded that despite Bosnian Serb and Serbian media reports of terrorist cells, the risk of a terrorist attack in Bosnia and Herzegovina 'is not higher than in other parts of the world'.[40]

Notable people

- Abu Sulaiman al-Makki, Saudi[41]

- Ahmed Zuhair–Abu Handala, Saudi[41]

- Abdelkader Mokhtari–Abu el-Ma'ali (d. 2015), Algerian; GIA member

- Mustafa Kamel Mustafa–Abu Hamza al-Masri (born 1958), Egyptian; Islamist imam, later guilty on terrorism charges in Britain and the US

- Nasser bin Ali al-Ansi (1975–2015), Yemeni; Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula leader

- Haroon Rashid Aswat (b. 1979), Indian-British; alleged Al-Qaeda member

- Karim Said Atmani (N/A), Moroccan; GIA member, suspected Charlie Hebdo shooting associate

- Nawaf al-Hazmi (1976–2001), Saudi; Al Qaeda member and 9/11 hijacker

- Khalid al-Mihdhar (1975–2001), Saudi; Al Qaeda member and 9/11 hijacker

- Fateh Kamel (b. 1961), Algerian; later guilty on terrorism charges in France

- Abdullah al-Rahman–Abu Khayr al-Masri (1957–2017), Egyptian; EIJ member and Al-Qaeda deputy leader

- Zuher al-Tbaiti (N/A), Saudi; later guilty on terrorism charges in Morocco

- Nasser al-Bahri–Abu Jandal (1972–2015), Saudi; Al-Qaeda member

- Babar Ahmad (b. 1974), Pakistani-British; later guilty on terrorism charges in the US

- Lionel Dumont (b. 1971), French;

- Abdel Rahman al Dosari–Abu Abdel Aziz "Barbaros"

- Imad al-Husein–Abu Hamza al-Suri[42]

- Adil al-Ghanim–Abu Mu'adh al-Kuwaiti ( †1995)

- al-Battar al-Yemeni

- Ali Hammad

- Ismail Royer, American[43]

See also

References

- ↑ ICG & 26 February 2013, p. 14.

- ↑ Shrader 2003, p. 51.

- 1 2 Berger 2011, p. 55.

- 1 2 Innes 2006, p. 157.

- ↑ CSIS, Foreign Fighters: Bosnia.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Lebl 2014, p. 8.

- ↑ Farmer 2010, p. 126.

- ↑ Fisk, Robert (7 September 2014). "After the atrocities committed against Muslims in Bosnia, it is no wonder today's jihadis have set out on the path to war in Syria". The Independent.

- ↑ Hunter, Shireen T. (2016). God on Our Side: Religion in International Affairs. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 164. ISBN 978-1-4422-7259-0.

- ↑ Humanitarian worker turned Mujahideen

- 1 2 3 4 5 ICTY: Summary of the judgement for Enver Hadžihasanović and Amir Kubura - "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-28. Retrieved 2010-02-05.

- ↑ ICTY, Summary of the Judgment for Enver Hadzihasanovic and Amir Kubura, 15 March 2006. See section "VI. The Mujahedin"

- ↑ Spero News, Bosnia: Muslims upset by Wahhabi leaders, Adrian Morgan, 13 November 2006

- 1 2 LA Times, Bosnia Seen as Hospitable Base and Sanctuary for Terrorists, 8 October 2001

- 1 2 "Predrag Matvejević analysis". Archived from the original on 2012-12-08.

- ↑ Schindler 2007, p. 224.

- 1 2 3 "ICTY - TPIY :". Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ↑ Curtis 2011, p. 207.

- ↑ The American Conservative, The Bosnian Connection, by Brendan O’Neill, 16 July 2007

- ↑ "ICTY: Milomir Stakić judgement - The media".

- ↑ "ICTY: Duško Tadić judgement - Greater Serbia".

- 1 2 "ICTY: Kordić and Čerkez verdict - IV. Attacks on towns and villages: killings - 2. The Conflict in Gornji Vakuf".

- ↑ "SENSE Tribunal: Poziv na predaju". Archived from the original on 2008-06-04.

- ↑ "SENSE Tribunal: Ko je počeo rat u Gornjem Vakufu". Archived from the original on 2008-06-04.

- ↑ "SENSE Tribunal: "James Dean" u Gornjem Vakufu". Archived from the original on 2008-06-04.

- ↑ Deliso 2007, p. 18.

- ↑ "BBC News - EUROPE - Mujahideen fight Bosnia evictions". Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ↑ "ICTY - TPIY :". Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ↑ ICTY indictment against Rasim Delic

- ↑ "Mirsad Kebo: Novi dokazi o zločinima nad Srbima". Nezavisne.com. Retrieved 2016-09-04.

- ↑

- ↑ "Kebo To Show Evidence Izetbegovic Brought Mujahideen To Bosnia | Срна". Srna.rs. Retrieved 2016-09-04.

- ↑ Denis Dzidic. "Bosnian Party Accused of Harbouring War Criminals". Balkan Insight. Retrieved 2016-09-04.

- 1 2 3 Berger 2011, p. 153.

- ↑ 9/11 Commission Report, Chapter 5.2, pp. 153–159

- ↑ Joscelyn, Thomas; Adaki, Oren (1 October 2014). "AQAP official calls on rival factions in Syria to unite against West". The Long War Journal. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ↑ "Bosnia Jails Salafist Chief for Recruiting Fighters". BalkanInsight. 5 November 2015. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ↑ PBS Newshour with Jim Jim Lehrer, A New Constitution for Bosnia, 22 November 2005

- 1 2 RFE - Al-Qaeda In Bosnia-Herzegovina: Myth Or Present Danger - Chapter: Myth Or Present Danger? "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-10-12. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- ↑ Juan Carlos Antúnez (16 September 2008). "5. Wahhabi links to international terrorism". Wahhabism in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Part One. Bosnian Institute.

- 1 2 Kohlmann 2004, p. 198.

- ↑ Galdini, Franco; Foreign Policy In Focus (December 19, 2013). "From Syria to Bosnia: Memoirs of a Mujahid in Limbo". The Nation.

- ↑ Berger 2011.

Sources

- Books

- Berger, J. M. (2011). Jihad Joe: Americans Who Go to War in the Name of Islam. Potomac Books, Inc. pp. 55–. ISBN 978-1-59797-693-0.

- Curtis, Mark (2010). Secret Affairs: Britain's Collusion with Radical Islam. Profile Books. ISBN 1-84668-763-2.

- Curtis, Mark (2011). Secret Affairs: Britain's Collusion with Radical Islam (Updated ed.). Profile Books. ISBN 1-84765-301-4.

- Deliso, Christopher (2007). The Coming Balkan Caliphate: The Threat of Radical Islam to Europe and the West. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-99525-6.

- Farmer, Brian R. (2010). Radical Islam in the West: Ideology and Challenge. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-6210-0.

- Innes, Michael A. (2006). Bosnian Security After Dayton: New Perspectives. Routledge. pp. 157–. ISBN 978-1-134-14872-1.

- Kohlmann, Evan (2004). Al-Qaida's Jihad in Europe: The Afghan-Bosnian Network. Berg Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85973-802-3.

- Schindler, John R. (2007). Unholy Terror. Zenith Imprint. ISBN 978-1-61673-964-5.

- Shrader, Charles R. (2003). The Muslim-Croat Civil War in Central Bosnia: A Military History, 1992-1994. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-58544-261-4.

- Moghadam, Assaf (2011). The Globalization of Martyrdom: Al Qaeda, Salafi Jihad, and the Diffusion of Suicide Attacks. JHU Press. ISBN 9781421400587.

- Case studies

- "Bosnia", Foreign Fighters, CSIS

- International Crisis Group (26 February 2013). "Bosnia's Dangerous Tango: Islam and Nationalism" (PDF). Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- Lebl, Leslie S. (2014). "Islamism and Security in Bosnia-Herzegovina" (PDF). Army War College.

Further reading

- Radio Free Europe - Al-Qaeda In Bosnia-Herzegovina: Myth Or Present Danger, Vlado Azinovic's research about the alleged presence of Al-Qaeda in Bosnia and the role of Arab fighters in the Bosnian War

- The Afghan-Bosnian Mujahideen Network in Europe, by, Evan F. Kohlmann. The paper was presented at a conference held by the Swedish National Defence College's Center for Asymmetric Threat Studies (CATS) in Stockholm in May 2006 at the request of Dr. Magnus Ranstorp - former director of the St. Andrews University Centre for the Study of Terrorism and Political Violence - and now Chief Scientist at CATS. It is also the title of a book by the same author.

- Mlivončić, Ivica. Al Qaida se kalila u Bosni i Hercegovini: mjesto i uloga mudžahida u Republici Hrvatskoj i Bosni i Hercegovini od 1991. do 2005. godine. Naša ognjišta, 2007.

- Mustapha, Jennifer. "The Mujahideen in Bosnia: the foreign fighter as cosmopolitan citizen and/or terrorist." Citizenship Studies 17.6-7 (2013): 742-755.

- Mincheva, Lyubov G., and Ted Robert Gurr. "Unholy Alliances: Evidence on Linkages between Trans-State Terrorism and Crime Networks: The Case of Bosnia." Transnational Terrorism, Organized Crime and Peace-Building. Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2010. 190-206.

- Van Zuijdewijn, Jeanine de Roy, Edwin Bakker, and ICCT Background Note. "Returning Western foreign fighters: The case of Afghanistan, Bosnia and Somalia." The Hague: International Centre for Counter-Terrorism (2014).

- Kurop, Marcia Christoff. "Al Qaeda's Balkan Links." The Wall Street Journal: November 1 (2001).

- Kroeger, Alix. "Mujahideen fight Bosnia evictions." (2008).

- Innes, Michael A. "Terrorist sanctuaries and Bosnia-Herzegovina: Challenging conventional assumptions." Studies in conflict & terrorism 28.4 (2005): 295-305.

- Zosak, Stephanie. "Revoking citizenship in the name of counterterrorism: the citizenship review commission violates human rights in Bosnia and Herzegovina." Nw. UJ Int'l Hum. Rts. 8 (2009): 216.

- Trifunovic, Darko. "Islamic Radicalization process in South East Europe (Case study Bosnia)."

- Gibas-Krzak, D. (2013). "Contemporary Terrorism in the Balkans: A Real Threat to Security in Europe". The Journal of Slavic Military Studies. Taylor & Francis. doi:10.1080/13518046.2013.779861.

External links

- ICTY - FINAL JUDGMENT FOR HADZIHASANOVIC AND KUBURA

- Radio Free Europe - Al-Qaeda In Bosnia-Herzegovina: Myth Or Present Danger (in Bosnian)

- Radio Free Europe - Bosnia-Herzegovina: New Book Investigates Presence Of Al-Qaeda

- Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN), CTY: BiH Army Knew About Mujahedin Crimes, 8 September 2007

- Bosnian fears rise over Islamic extremism, Financial Times, June 29, 2010

- Bosnia-Herzegovina raids ‘Islamist’ village, Financial Times, February 2, 2010