Egyptian cobra

| Egyptian cobra | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Serpentes |

| Family: | Elapidae |

| Genus: | Naja |

| Species: | N. haje |

| Binomial name | |

| Naja haje | |

| |

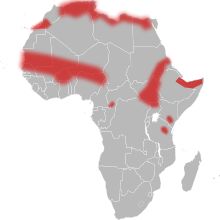

Distribution of the Egyptian Cobra | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

The Egyptian cobra (Naja haje) is a species of venomous snake in the family Elapidae. Naja haje is one of the largest cobra species native to Africa, second to the forest cobra (Naja melanoleuca).

Etymology

Naja haje was first described by Swedish zoologist Carl Linnaeus in 1758. The generic name naja is a Latinisation of the Sanskrit word nāgá (नाग) meaning "cobra". The specific epithet haje is derived from the Arabic word hayya (حية) which literally means "snake".[3]

Description

The Egyptian cobra is one of the largest cobras of the African continent. The head is large and depressed and slightly distinct from the neck. The neck of this species has long cervical ribs capable of expanding to form a hood, like all other cobras. The snout of the Egyptian cobra is moderately broad and rounded. The eye is quite big with a round pupil. The body of the Egyptian cobra is cylindrical and stout with a long tail. The length of the Egyptian cobra is largely dependent on subspecies, geographical locale, and population. The average total length (including tail) of this species is between 1 and 2 metres (3.3 and 6.6 ft), with a maximum total length of just under 3 metres (9.8 ft). The most recognizable characteristics of this species are its head and hood. The colour is highly variable, but most specimens are some shade of brown, often with lighter or darker mottling, and often a "tear-drop" mark below the eye. Some are more copper-red or grey-brown in colour. Specimens from northwestern Africa (Morocco, western Sahara) are almost entirely black. The ventral side is mostly a creamy white, yellow brown, grayish, blue grey, dark brown or black in colouration, often with dark spots.[4]

Scalation

Naja haje has the following scalation. The dorsal scales at midbody number 19-20. The ventral scales number 191-220. The anal plate is single. The subcaudal scales are paired and number 53-65. There is 1 preocular, 3 (or 2) postoculars, and 2 or 3 suboculars. The upper labials number 7 (rarely 6 or 8), and are separated from the eye by the suboculars. The lower labials number 8. The temporal scales are arranged 1+2 or 1+3, varying.[4]

Geographic range

_at_Jacksonville_Zoo.jpg)

The Egyptian cobra ranges across most of North Africa north of the Sahara, across the savannas of West Africa to the south of the Sahara, south to the Congo basin and east to Kenya and Tanzania. Older literature records from southern Africa and the Arabian Peninsula refer to other species (see Taxonomy section below).

In zoos

The Egyptian cobra can also be found in captivity at zoos both in and outside of the snake’s natural range. The Giza Zoo[5] and the San Diego Zoo[6] as well as the Virginia Aquarium include the Egyptian Cobra in their reptile collections.

Bronx Zoo escape

On March 26, 2011, the Bronx Zoo informed the public that their reptile house was closed after a venomous adolescent female banded Egyptian cobra was discovered missing from its off-exhibit enclosure on March 25.[7] Zoo officials were confident the missing cobra would be found in the building and not outside, since the Egyptian cobra is known to be uncomfortable in open areas.[8] The snake's metabolism would also have been impacted by the cold weather outdoors at that time in the Bronx. The cobra was found in a dark corner of the zoo's reptile house on March 31, 2011, in good health.[9] After a contest, she was named "Mia" for "missing in action."

Habitat

Naja haje occurs in a wide variety of habitats like, steppes, dry to moist savannas, arid semi-desert regions with some water and vegetation. This species is frequently found near water. The Egyptian cobra is also found in agricultural fields and scrub vegetation. It also occurs in the presence of humans where it often enter houses. It is attracted to villages by rodent pests (rats) and domestic chickens. There are also notes of the Egyptian cobra swimming in the Mediterranean sea, so it seems to like water where it has been found quite often.[4][10]

Behaviour and ecology

The Egyptian cobra is a terrestrial and crepuscular or nocturnal species. It can however, be seen basking in the sun at times in the early morning. This species shows a preference for a permanent home base in abandoned animal burrows, termite mounds or rock outcrops. It is an active forager sometimes entering human habitations, especially when hunting domestic fowl. Like other cobra species, it generally attempts to escape when approached, at least for a few metres, but if threatened it assumes the typical upright posture with the hood expanded, and strikes. This species prefers to eat toads, but it will prey on small mammals, birds, eggs, lizards and other snakes.[10][11]

Venom

The venom of the Egyptian cobra consists mainly of neurotoxins and cytotoxins.[12] The average venom yield is 175 to 300 mg in a single bite, and the murine subcutaneous LD50 value is 1.15 mg/kg.[13]

The venom affects the nervous system, stopping the nerve signals from being transmitted to the muscles and at later stages stopping those transmitted to the heart and lungs as well, causing death due to complete respiratory failure. Envenomation causes local pain, severe swelling, bruising, blistering, necrosis and variable non-specific effects which may include headache, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, dizziness, collapse or convulsions along with possible moderate to severe flaccid paralysis. Unlike some other African cobras (for example the red spitting cobra), this species does not spit venom.[14]

Other cultures

In Ancient Egyptian culture and history

The Egyptian cobra was represented in Egyptian mythology by the cobra-headed goddess Meretseger. A stylised Egyptian cobra — in the form of the uraeus representing the goddess Wadjet — was the symbol of sovereignty for the Pharaohs who incorporated it into their diadem. This iconography was continued through the end of the ancient Egyptian civilization (30 BC).

Most ancient sources say that Cleopatra and her two attendants committed suicide by being bitten by an aspis, which translates into English as "asp". The snake was reportedly smuggled into her room in a basket of figs. Plutarch wrote that she performed experiments on condemned prisoners and found aspis venom to be the most painless of all fatal poisons.[15] This "aspis" was likely to be Naja haje (the Egyptian cobra). However, the accounts of her apparent suicide have been questioned, since death from this snake's venom is relatively slow and it can cause damage to the tissue sometimes, and the snake is large, so it would be hard to conceal.[16]

As a pet

The Egyptian cobra garnered increased attention in Canada in the fall of 2006 when a pet cobra became loose and forced the evacuation of a house in Toronto[17] for more than six months when it was believed to have sought refuge in the home's walls. The owner was fined $17,000 and sentenced to jail.[18]

In magic acts

In July, 2018, Aref Ghafouri was bitten by an Egyptian cobra while preparing for a show in Turkey. He was evacuated to Egypt for treatment with the anti-venom, and, made a full recovery.[19]

Taxonomy

The specific name haje is the transliteration of Arabic حية which is the word for snake or viper. The snouted cobra (Naja annulifera) and Anchieta's cobra (Naja anchietae) were formerly regarded as subspecies of Naja haje, but have since been shown to be distinct species.[20][21] The Arabian populations were long recognised as a separate subspecies, Naja haje arabica, and the black populations from Morocco sometimes as Naja haje legionis. A recent study[22] found that the Arabian cobra constitutes a separate species, Naja arabica, whereas the subspecies legionis was synonymised with N. haje. The same study also identified the West African savanna populations as a separate species and described it as Naja senegalensis.

References

| Wikispecies has information related to Naja haje |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Naja haje. |

- ↑ "Naje haje haje". ITIS Standard Report Page. ITIS.gov. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ↑ "Naja haje ". The Reptile Database. www.reptile-database.org.

- ↑ Wuster, Wolfgang; Wallach, Van; Broadley, Donald G. (2009). "In praise of subgenera: taxonomic status of cobras of the genus Naja Laurenti (Serpentes: Elapidae)" (PDF). Zootaxa. 2236 (1): 26–36. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- 1 2 3 Mastenbroek, Richard. "Captive Care of the Egyptian Cobra (Naja haje)" (PDF). Devenomized. www.devenomized.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ↑ "Egyptian cobra". Gizazoo-eg.com. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ↑ "Reptiles: Cobra Quick Facts". sandiegozoo.org. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ↑ Gootman, Elissa; Kilgannon, Corey (31 March 2011). "Bronx Zoo Cobra Found Alive". The New York Times.

- ↑ Kevin Dolak (27 March 2011). "Bronx Zoo Reptile House Closed After Poisonous Snake Goes Missing". ABC News. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- ↑ staff and wire (31 March 2011). "Missing Bronx Zoo cobra found, officials confirm". MSNBC. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- 1 2 "Naja haje - General Details, Taxonomy and Biology, Venom, Clinical Effects, Treatment, First Aid, Antivenoms". WCH Clinical Toxinology Resource. University of Adelaide. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ↑ Filippi, E., Petretto, M, Naja haje (Egyptian Cobra) Diet/Ophiophagy in Herpetological Review 2013; 44: 155-156

- ↑ Joubert, FJ; Taljaard N (October 1978). "Naja haje haje (Egyptian cobra) venom. Some properties and the complete primary structure of three toxins (CM-2, CM-11 and CM-12)". European Journal of Biochemistry. 90 (2): 359–367. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1978.tb12612.x. PMID 710433.

- ↑ Fry, Dr. Bryan Grieg. "Sub-cutaneous LD-50s". Australian Venom Research Unit. University of Queensland. Archived from the original on 13 April 2012. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ↑ Bogert, C.M. (1943) Dentitional phenomena in cobras and other elapids with notes on adaptive modifications of fangs. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 81, 285–360.

- ↑ Plutarch Parallel Lives, "Life of Antony"

- ↑ Richard Girling Cleopatra and the asp The Times November 28, 2004

- ↑ "CBC: Escaped venomous cobra in Toronto wanted dead or alive". Cbc.ca. 2006-10-19. Archived from the original on May 13, 2010. Retrieved 2013-08-11.

- ↑ "CBC: Owner of deadly pet cobra jailed, fined $1,000,000". Cbc.ca. 2007-03-08. Archived from the original on May 13, 2010. Retrieved 2013-08-11.

- ↑ "A Cobra Strikes. A Magician Is Stricken. Middle Eastern Foes Unite". Retrieved 2018-07-21.

- ↑ Broadley, D.G. (1995) The snouted cobra, Naja annulifera, a valid species in southern Africa. Journal of the Herpetological Association of Africa, 44, 26–32.

- ↑ Broadley, D.G. & Wüster, W. (2004) A review of the southern African ‘non-spitting’ cobras (Serpentes: Elapidae: Naja). African Journal of Herpetology, 53, 101–122.

- ↑ Trape, J.-F., L. Chirio, D.G. Broadley & W. Wüster (2009) Phylogeography and systematic revision of the Egyptian cobra (Serpentes: Elapidae: Naja haje) species complex, with the description of a new species from West Africa. Zootaxa 2236: 1-25.

External links

Further reading

- Boulenger GA (1896). Catalogue of the Snakes in the British Museum (Natural History). Volume III., Containing the Colubridæ (Opisthoglyphæ and Proteroglyphæ) ... London: Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History). (Taylor and Francis, printers). xiv + 727 pp. + Plates I-XXV. ("Naia haie [sic]", pp. 374-375).

- Linnaeus C (1758). Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, diferentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio Decima, Reformata. Stockholm: L. Salvius. 824 pp. (Coluber haje, new species, p. 225). (in Latin).